Eu Tong Sen’s “Pearl Under the Burning Tropical Sun”

The grandeur and opulence of Eu Villa on Mount Sophia was unrivalled in its heyday.

By Patricia Lin

Eu Villa, the home of Eu Tong Sen (1877–1941), was perhaps the most spectacular mansion to be built in Singapore in the early years of the 20th century that was owned by a Straits Chinese. Nicknamed “the King of Tin”, Eu was also the man behind traditional Chinese medicine retailer Eu Yan Sang.

Eu Villa, 1979. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Eu Villa, 1979. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Eu was born in Penang on 23 July 1877 but received his early education in Foshan, China. His father Eu Kong, who left his hometown of Foshan for Penang in 1873, was a self-made millionaire. The elder Eu had the foresight to later venture into business in the then remote town of Gopeng in the Kampar district of Perak.1

Portrait of Eu Tong Sen. Image reproduced from Song Ong Siang, One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore (London: John Murray, 1923), 332. Collection of the National Library, Singapore (Accession no. B20048226B).

Portrait of Eu Tong Sen. Image reproduced from Song Ong Siang, One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore (London: John Murray, 1923), 332. Collection of the National Library, Singapore (Accession no. B20048226B).Eu took over his father’s business at the relatively early age of 21 following the latter’s untimely death in 1890. He parlayed his father’s concerns into mining, rubber, banking, traditional Chinese medicine, entertainment and hotels. Like many of the Chinese entrepreneurs of his time, Eu’s wealth was also accrued through the acquisition of British monopolies for opium, alcohol and gambling.2

An Opulent Mansion

Eu Villa on Adis Road was the third mansion to be built at the site on Mount Sophia. The first home belonged to Municipal Engineer W.T. Carrington, who had purchased the two-acre property from merchant Charles Robert Prinsep and built Carrington House sometime around 1873 (by 1840, Prinsep had established a huge nutmeg and coffee plantation on the hill and in the surrounding areas). Little is known about the house and who owned it following Carrington’s death in 1878.3

Eu Villa, 1940. Edward William Newell Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Eu Villa, 1940. Edward William Newell Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.In 1903, the house was purchased by Nissim N. Adis, the Calcutta barrister and businessman. Adis demolished the Carrington edifice and built a luxurious mansion that came to be known as Adis Lodge. It had a steel and concrete construction, and a commanding view of Singapore. The mansion had eight bedrooms and boasted a bathroom for each bedroom, with hot and cold running water.4

The Adis family occupied their lodge for less than 10 years before the property was purchased by Eu Tong Sen. Evidently unimpressed by the elegance and opulence of Adis Lodge, he proceeded to demolish the building and build the villa that would be unrivalled for decades.5 Eu Villa would be only one of a string of luxurious mansions that he commissioned to be built in Singapore, Hong Kong (where he had two palatial homes), Gopeng and Kuala Lumpur.6 Rumour has it that Eu had been told by a seer that he had to keep building if he wished to live a long life, and build he did.

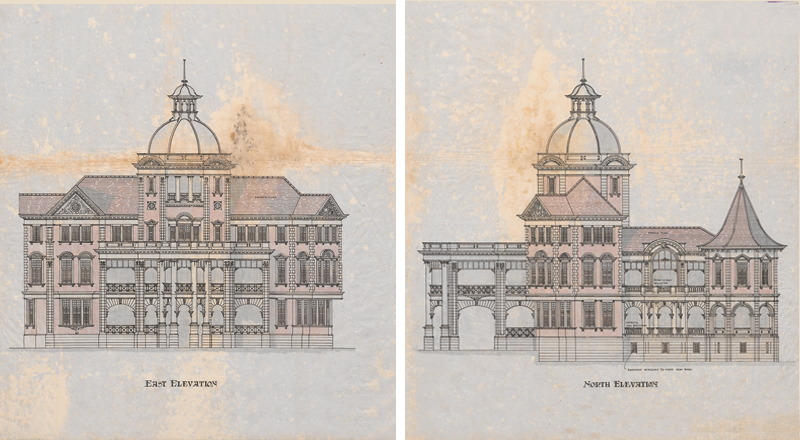

Eu Villa, which commanded a panoramic view of the town and harbour, was designed by the architectural firm of Swan & Maclaren for a million dollars and completed in 1913. “Eu Villa has the mark of a millionaire in all its commodious premises. It is built like a chateau – the French influence is strong – and its dull-white exterior shines like a pearl under the burning tropical sun,” reported the Straits Times in 1934.7

An aerial view of Eu Villa on Mount Sophia, 1940s. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

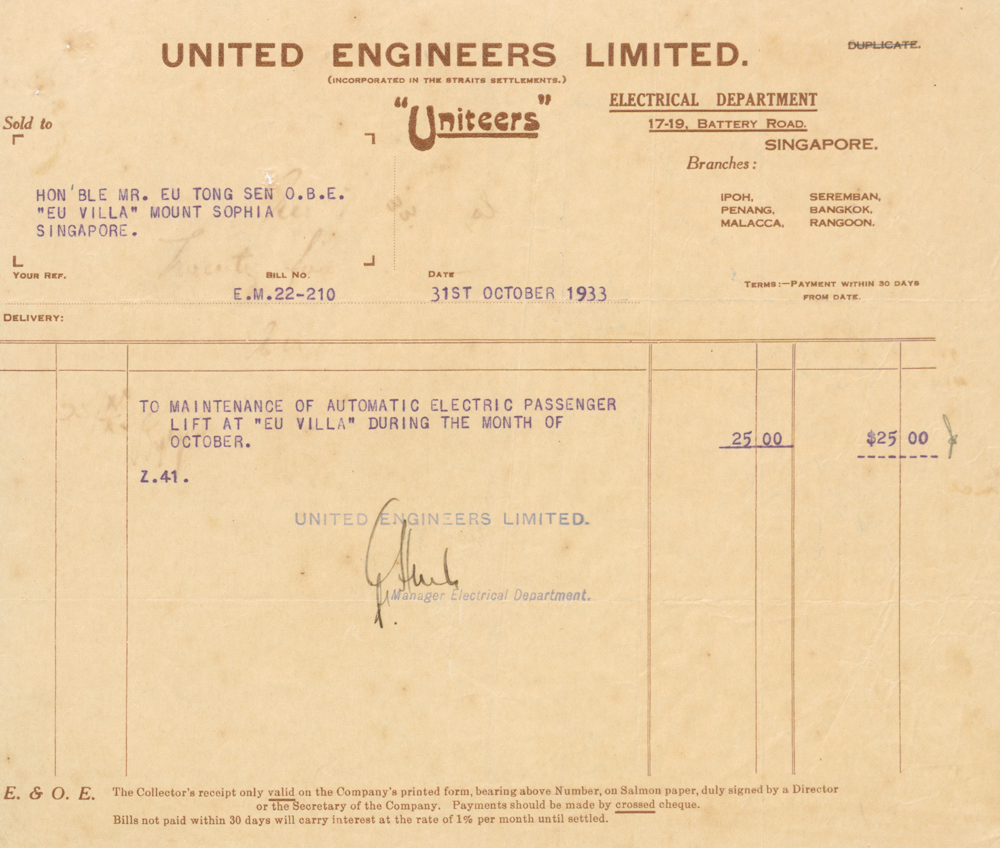

An aerial view of Eu Villa on Mount Sophia, 1940s. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.The villa’s main building was five storeys high and had a dome. The villa also had a basement and wine cellar, and in addition to the stairs, it had “an electric passenger-controlled lift” said to be “the first of its kind in this part of the world”. Eu had installed the lift for his mother to take to the top floor to enjoy the view.8 In early 1916, a telephone with the number 44 was installed in the villa.9

A bill from United Engineers Limited dated 31 October 1933 for the maintenance fee of $25 for the electric lift in Eu Villa. Koh Seow Chuan Collection, National Library Singapore.

A bill from United Engineers Limited dated 31 October 1933 for the maintenance fee of $25 for the electric lift in Eu Villa. Koh Seow Chuan Collection, National Library Singapore.Although described as being built along the lines of a French chateau, Eu Villa’s design was more in keeping with the Edwardian Baroque style with its eclectic integration of Florentine and other embellishments which its owner apparently favoured. These included the dome that would become the signature feature of the villa.

According to architect Lee Kip Lin, Eu Villa’s drum and lantern dome was probably one of the earliest seen in Singapore’s private homes, and that similar domes would later appear on the homes of Chinese businessmen Low Teng Lin and Teo Hoo Lye.10

The 1913 building plan of Eu Tong Sen’s Eu Villa showing the east and north elevations (1413–7/1913). Building Control Division Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The 1913 building plan of Eu Tong Sen’s Eu Villa showing the east and north elevations (1413–7/1913). Building Control Division Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Marble and Statues

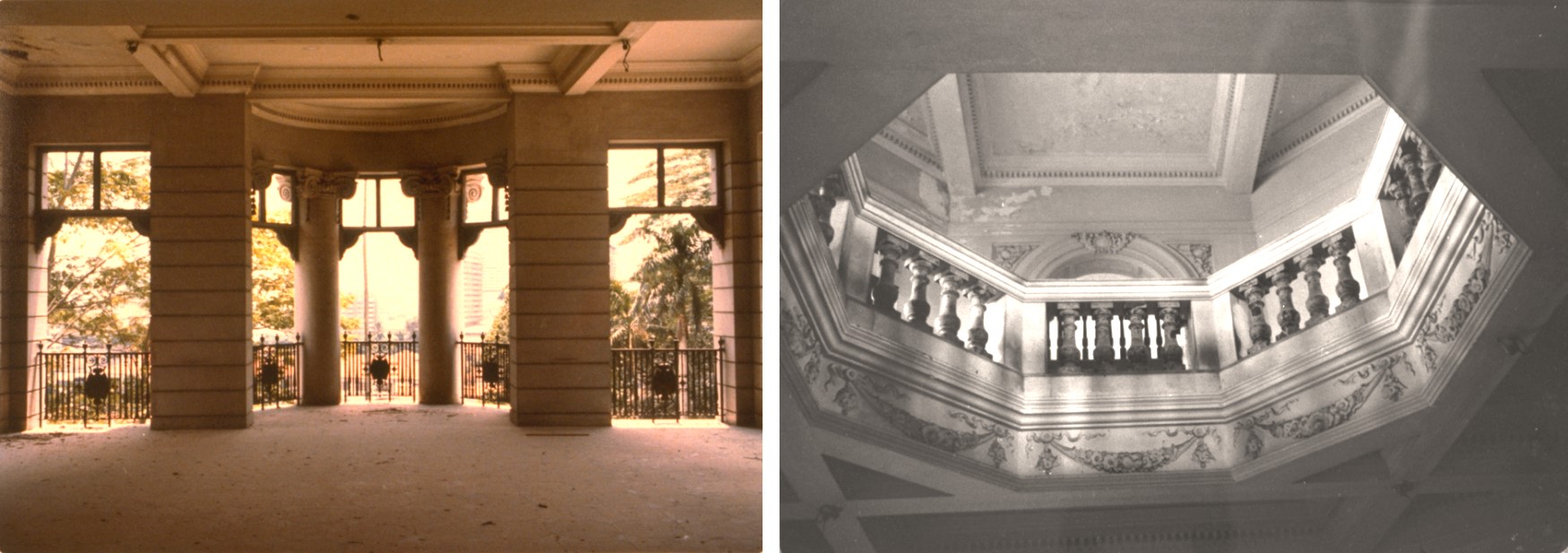

Another feature that came to be unique to Eu Villa was the copious use of marble which Eu loved. There were sea-green marble pillars, floors with marble of every colour possible and marble statues in the garden as well as in the villa itself.

The statues depicting mythological figures such as Phrine, Eve, Bacchante, the huntress Dinah, Apollo and Venus were all provided by Raoul Bigazzi from Florence. The company, which specialised in marble statues, mosaics, bronze work and floors, was also responsible for the work done on Chartered Bank, the Municipal Building, the Supreme Court, Hong Kong Bank and the Union Insurance Building in Singapore before World War II. After the war, the company provided and installed the marble for the Bank of China, the Lim Bo Seng Memorial and Finlayson House in Singapore, among the many other buildings throughout Asia.11

One of the frescoes in Eu Villa, 1979. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

One of the frescoes in Eu Villa, 1979. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Murals and artworks by Italian painter Egisto Ferroni, Austrian Impressionist and artist Franz Hofer, and British artists John Sargent Noble and Alexander Mark Rossi were scattered throughout Eu Villa. A full-length portrait of Eu painted in 1928 graced the billiard room, while a life-sized bronze statue was placed in the living room.

The furnishings throughout the mansion were an eclectic mix, with most of the furniture supplied by the finest stores in London and Paris. The drawing room featured gilt furniture in the style of Louis XIV, while Chinese chairs adorned the dining room. The floors were lined with Chinese and Persian carpets.12

Building an Annex

Within the first few years of his occupancy, Eu deemed his dining room too small to accommodate the ever-growing numbers at his dinner parties. An annex was built to the main house with a dining room that could comfortably seat one hundred guests on the ground floor, while the second floor housed a ballroom that was the same size as the one in Raffles Hotel.13

The interior of Eu Villa, 1979. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The interior of Eu Villa, 1979. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.As a member of “the King’s Chinese”,14 Eu was mindful to hang an oil painting of King George V and Queen Mary prominently overlooking the dining room. Two massive gongs in the shape of bells summoned guests to dinner in the dining room lit by three huge chandeliers.15

The staircase leading up to the ballroom was flanked by a pair of Florentine nudes in white marble and the stairs themselves were carpeted in red plush. In its heyday, the ballroom was said to have been the scene of many a glittering event. A key feature of the ballroom was the large stained glass windows.16

The stained glass windows above the doors. Lee Kip Lin Collection, National Library Singapore.

The stained glass windows above the doors. Lee Kip Lin Collection, National Library Singapore.At least nine other pairs of stained glass windows in the Art Nouveau style, made by the stained glass artist H.V. McGoldrik, were also installed in other parts of the villa. The ones in the ballroom were of “Dawn” and “Night”, while others throughout the villa depicted Greek mythological figures such as Orpheus, Pan, Bacchus, Neptune and Psyche. The estimated cost for each of these stained glass windows at the time was around £700.17

The ceiling with the stained glass windows, 1975. Lee Kip Lin Collection, National Library Singapore.

The ceiling with the stained glass windows, 1975. Lee Kip Lin Collection, National Library Singapore.Bedrooms and Bathrooms

There were at least 10 bedrooms, attached bathrooms and boudoirs on all three floors of the villa. Eu’s personal suite on the second floor included a sitting room with inlaid walnut and a bedroom in mahogany. His bathroom, described as being as “large as a normal bedroom and is handsome” was tiled with oak.18

The second floor also had two other bedrooms, a small ballroom and an enormous veranda with its own marble fountain. Placed on one side of the verandah was an electric violina and on the other side an electric organ.19

More bedrooms and bathrooms were found on the third floor, which also boasted a supper room and card room, both richly furnished.20

Other Amenities

The sheer size of Eu Villa accordingly necessitated a large kennel of dogs to patrol and guard the property.21 The security staff included five watchmen and a pack of Alsatians, Mastiffs and Great Danes.

With the huge amount of expensive jade, statues, paintings, jewellery and other precious artifacts in the villa, security was a major concern for the household. All in all, it was estimated that there were about a hundred servants, chauffeurs, gardeners, dog handlers, amahs and cooks who attended to and served the Eu family.22

Eu had 11 wives who variously provided him with 13 sons and nine daughters. To accommodate the enormous family, an annex that came to be called “The Spanish House” was built to house the sons.23

Eu owned a fleet of six cars, including a Rolls Royce and a 44 hp supercharged seven-seater Bentley.24

Philanthropic Endeavours

Eu’s interest in modern machines was not restricted to his personal effects. As a committed “King’s Chinese”, he contributed one of the planes that formed part of the World War I “Malaya Squadron”. The aircraft, a B.E.2c named “Malaya 1”, was flown overseas by a member of the Royal Flying Corps in November 1915. It was part of a five-plane squadron – one fighter plane and four reconnaissance planes – of which the “Malaya 1” was the lead plane. Each plane cost £2,250.25

In addition to his donation of an airplane, Eu also gave the British military £6,000 for the purchase of a tank in 1917.26 The tank, which saw action at the Battle of Cambrai, was unique in that following the Chinese tradition of painting boats and other vessels with eyes, the tank went into battle with a large eye painted on each side of its bow.

Dubbed the “bus” by Captain Thurston who was charged with the six tanks involved in the Battle of Cambrai, Eu’s tank was said to be still going strong in 1918 and ready to “knock out anything Bochelike [i.e. German made] that comes in her vicinity”.27

Eu’s wide range of business interests invariably took him to locations where he had built other palatial homes. By the time of his death in 1941, his heirs were establishing his legal residency in order to settle his estate. Eu had lived mainly in Hong Kong since 1929, except for a period of about six months in 1933 when he returned to Singapore.28

After his departure from Singapore, Eu Villa continued to be home to his various wives, children and extended family.29 Eu’s widowed mother lived in Eu Villa until the end of her days.30

End of an Era

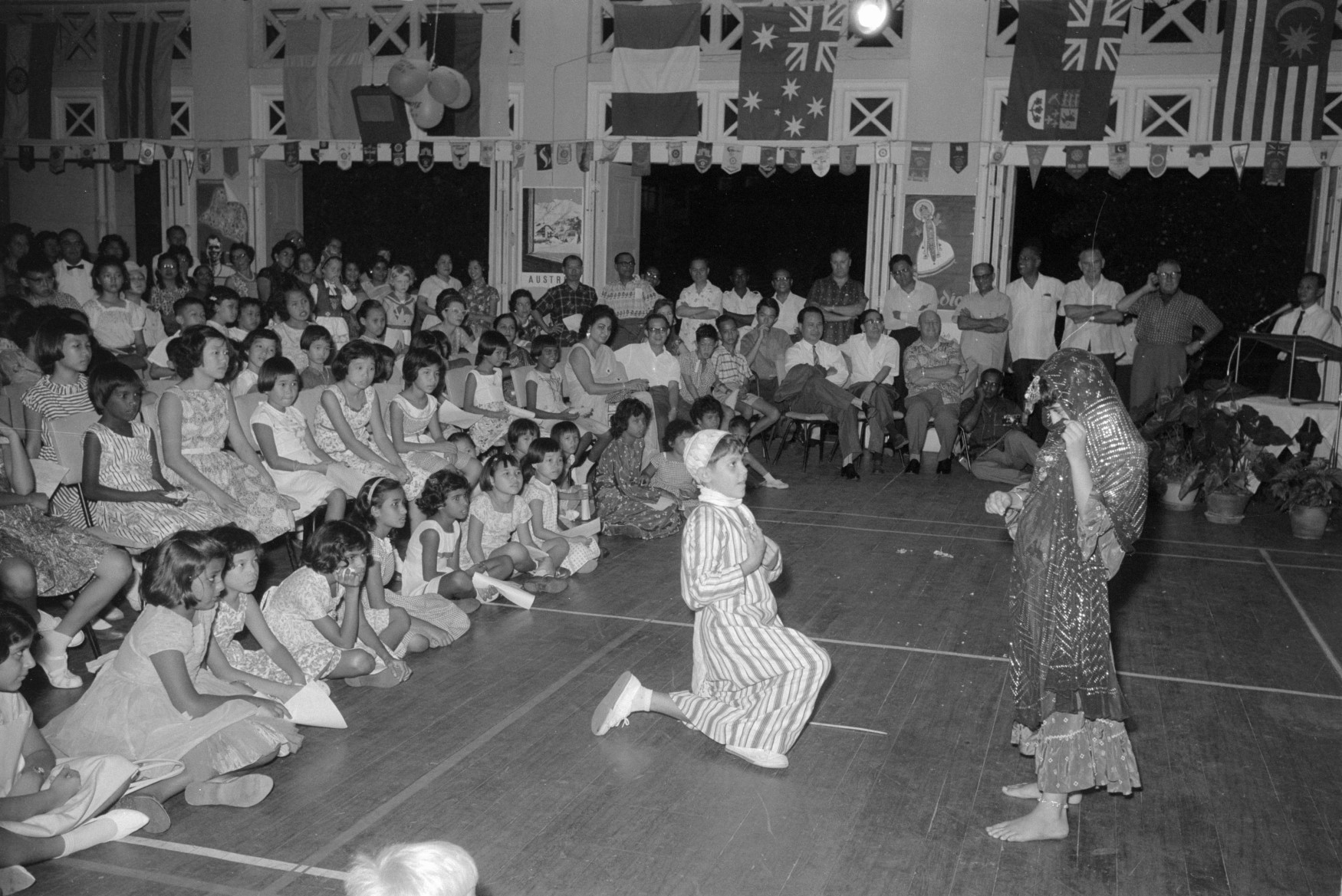

Throughout the 1950s, Eu Villa went on to be a place where parties, fundraisers and society events were held. Under the auspices of Mrs Diana Eu, wife of Richard Eu Keng Mun (a son of Eu Tong Sen), the villa was frequently the setting for bridge and mahjong drives by the Chinese Ladies’ Association in aid of different charities, including St Andrew’s Hospital, the Singapore Anti-Tuberculosis Association and the Singapore Boys’ Scouts Association.31

A children’s performance at Eu Villa, 1962. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A children’s performance at Eu Villa, 1962. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.In 1973, as various family members and their different business enterprises ran into difficulties, Eu Villa was sold after competitive bidding by several companies, including realty companies from Hong Kong. They were eventually outbid by Joiner Enterprises Pte. Ltd. of Cecil Street, Singapore, who paid $8.19 million for the venerable villa. The villa was demolished in the early 1980s to make way for condominium project, Sophia Court.32 (Sophia Court was sold in 2006 and on the site today is Sophia Residence.)

Besides Eu Villa, there were a number of other palatial mansions built for the wealthy Straits Chinese in the first quarter of the 20th century. However, neither the personalities of their owners nor the opulence of the houses themselves came close to rivalling the likes of Eu Tong Sen or his villa on Adis Road.

Dr Patricia Lin has a PhD in Comparative Literature and Critical Theory from the University of Southern California. She is retired Professor Emeritus in the Department of Gender, Ethnicity, and Multicultural Studies at California State Polytechnic University.

Dr Patricia Lin has a PhD in Comparative Literature and Critical Theory from the University of Southern California. She is retired Professor Emeritus in the Department of Gender, Ethnicity, and Multicultural Studies at California State Polytechnic University.Notes

-

Alex Chow, “Eu Tong Sen,” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published 15 September 2014; Arnold Wright and H.A. Cartwright, eds., Twentieth Century Impressions of British Malaya: Its History, People, Commerce, Industries, and Resources (London: Lloyd’s Greater Britain Publishing Company, 1908), 534–36. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.3 TWE) ↩

-

Wright and Cartwright, Twentieth Century Impressions of British Malaya, 534–36. ↩

-

Jerome Lim, “Sophia, Caroline and Emily, and the Spiced Up Hills of Babylon,” The Long and Winding Road, 18 August 2016, https://thelongnwindingroad.wordpress.com/2016/08/18/sophia-caroline-and-emily-and-the-spiced-up-hills-of-babylon/; Jerome Lim, “Adis Lodge – Another Crazy-Rich-Asian Mansion Near Dhoby Ghaut,” The Long and Winding Road, 10 December 2020, https://thelongnwindingroad.wordpress.com/tag/adis-road/. ↩

-

Lim, “Adis Lodge.” ↩

-

Lim, “Adis Lodge.” ↩

-

Wright and Cartwright, Twentieth Century Impressions of British Malaya, 534–36. ↩

-

“Mr Eu Tong Sen’s Million Dollar Villa,” Straits Times, 9 September 1934, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“This Week’s News,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 18 October 1917, 241. (From NewspaperSG); Seow Peck Ngiam, “Eu Tong Sen and His Business Empire,” BiblioAsia 12, no. 2 (July–September 2016): 58–64. ↩

-

“Telephone Directory,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 9 February 1916, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lee Kip Lin, The Singapore House 1819–1942 (Singapore: Times Editions [for] Preservation of Monuments Board, 1988), 130. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 728.095957 LEE) ↩

-

York Lo, “Raoul Bigazzi (卞根基) – Leading Specialist in Marbles, Bronzes and Mosaics in the Far East From the 1920s to the 1960s,” The Industrial History of Hong Kong Group, 10 June 2019, https://industrialhistoryhk.org/raoul-bigazzi-%E5%8D%9E%E6%A0%B9%E5%9F%BA-leading-specialist-in-marbles-bronzes-and-mosaics-in-the-far-east-from-the-1920s-to-the-1960s/; “It’s Rich With Italian Marble,” Singapore Free Press, 19 January 1955, 21. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

The Straits Chinese were loyal to the British Crown and became known as the “King’s Chinese”, distinct from the rest of their Chinese kin in their dress, language and attitudes. ↩

-

“Mr Eu Tong Sen’s Million Dollar Villa”; “Wedding Gift That’s Worth a ‘Fortune’,” Straits Times, 7 May 1974, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Violet Oon, “Our Heritage the ‘Dream House’ Will Soon Be Only a Memory,” New Nation, 13 July, 1973, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Eu Tong Sen Craft,” Pinang Gazette and Straits Chronicle, 9 November 1915, 4; C. Alma Baker, “Malayan Gifts of Aeroplanes,” Straits Times, 22 September, 1915, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Malaya’s ‘Tank,” Pinang Gazette and Straits Chronicle, 27 March 1917, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The ‘Eu Tong Sen’ Tanks,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 5 August 1918, 2; “Tank from Malaya,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 6 October 1919, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Malayan Multimillionaire Dies Suddenly in HongKong,” Pinang Gazette and Straits Chronicle, 12 May 1941, 7; “Eu Tong Sen Is Domiciled in HK,” Straits Times, 30 April 1952, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Violet Oon, “Our Heritage the ‘Dream House’ Will Soon Be Only a Memory,” New Nation, 13 July, 1973, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Portrait of Mrs. Diana Eu, Vice-President of Singapore Girl Guides Association, 1967, photograph, National Library Board. (From National Library Online) ↩

-

T.F. Hwang, “Eu Tong Sen Mansion Is Sold for $8.19 Mil,” Straits Times, 16 February 1973, 17; Lee Yew Meng, “Eu Villa Gives Way…,” New Nation, 20 June 1981, 12; Bernard Koh, “Postcards from the Past,” Straits Times, 24 February 2008, 58. (From NewspaperSG) ↩