Karikal Mahal: Stories Reimagined and Retold

History, research and compelling storytelling come together to bring the story of Karikal Mahal to life.

By Rowena Loh

24 January 2025

If you frequently pass by the Katong-Marine Parade area, a striking white mansion along Still Road South might have caught your eye. You might also have noticed the smaller house across the street that complements its charm. Once dubbed the Taj Mahal of Singapore, these architectural gems have gone through eras of neglect and transformation, and today houses two preschools separated by Still Road South. This grand dame is Karikal Mahal, and few know of her resilience and transformation – and legacy waiting to be rediscovered.

When Channel NewsAsia (CNA) opened its annual call for pitches in early 2023, we at Ochre Pictures leapt at the chance to bring Karikal Mahal’s fascinating story to life. Our concept for a docudrama series envisioned the mansion herself as the narrator, guiding viewers through three extraordinary chapters of her early history. First, the glittering rise and tragic fall of Moona Kader Sultan, also known as the “Cattle King”, who built her – a man driven by boundless ambition. Next, the enigmatic era of the Malayan Magic Circle, where magic, mystery and spectacle converged in her shadowy halls. Finally, her darkest chapter as a World War II internment camp for a brief but intense 16 days, where she bore silent witness to the unyielding spirit of humanity in the face of the horrors of war.

The series, Karikal Mahal: A Silent Witness, draws on inspiration and intrigue which began years before the CNA pitch. For more than two decades, Jean Yeo, executive producer of the series, has been captivated by the historic mansions. This fascination culminated in our 2015 telemovie The Circle House, which delved into the secrets of the Malayan Magic Circle. While doing research for our CNA pitch, we found this same fascination (or some say, obsession) in a compelling BiblioAsia article on Karikal Mahal written by author and researcher Dr. William L. Gibson.1 His detailed article brought new depth to our understanding of the mansion’s storied past and we invited him to share his insights as a key interviewee in our series.

Recreating Karikal Mahal

From the outset, we were aware of the epic task of recreating Karikal Mahal. Moona Kader Sultan named his estate Karikal Mahal – Karikal (or Karaikal) was his hometown in Southern India and “Mahal” means “palace” in Hindi and also “expensive” in Malay.2 The mansion’s original interior was a mystery, as there were limited records and photographs from the era when Moona Kader Sultan first built it. This left us with little more than fragments of history and our imaginations to guide us. Our one tangible clue was the black-and-white marble flooring still preserved in the building today – a design element inspired by Kader’s hometown of Karikal. Using this detail as a cornerstone, we cross-referenced images and descriptions of actual mansions in Karikal to craft a plausible interpretation of what Karikal Mahal might have looked like in its prime.

The National Archives of Singapore (NAS) was an invaluable resource in reimagining the mansion’s surroundings. Beyond detailed maps of the Still Road South area, we also found rare aerial photographs taken by the British Royal Air Force in the 1950s before land reclamation in the area began. These materials offered a bird’s eye view of the land surrounding Karikal Mahal and enabled us to reconstruct the wider exterior and grandeur of its once-sprawling compound with greater accuracy.

A 1958 aerial view of Telok Kurau in eastern Singapore, with seaside bungalows along Marine Parade Road visible. This area is around today’s Kuo Chuan Avenue and Still Road South. The estate on the right by the sea is the former Karikal Mahal, through which Still Road South now runs through. Aerial photographs by the British Royal Air Force between 1940 to 1970s, from a collection held by the National Archives of Singapore. Crown copyright.

A 1958 aerial view of Telok Kurau in eastern Singapore, with seaside bungalows along Marine Parade Road visible. This area is around today’s Kuo Chuan Avenue and Still Road South. The estate on the right by the sea is the former Karikal Mahal, through which Still Road South now runs through. Aerial photographs by the British Royal Air Force between 1940 to 1970s, from a collection held by the National Archives of Singapore. Crown copyright.From there, we were able to digitally recreate Karikal Mahal in all its glory. To provide a more immersive experience for the audience, CNA also commissioned a website that allows visitors to explore Karikal Mahal. The flythrough offers a virtual tour of various physical spaces and items of interest within the compound, providing intriguing details we uncovered during our research but were not included in the main series.

Images from the website Karikal Mahal: A Silent Witness

Images from the website Karikal Mahal: A Silent WitnessThe Rise and Fall of the Cattle King

Once the mansion was “built”, we faced our next challenge – transporting viewers into the world of the 1930s and introducing them to Moona Kader Sultan, a pivotal figure in the series’ first episode. While we learned much about him through interviews with his descendants, the richness of his story was also painstakingly pieced together through articles found on NewspaperSG, the National Library’s newspaper archives.

As one of the most successful businessmen of his time, these digitised records spanning the early 1900s were a treasure trove of insights. They chronicled his meteoric rise from humble beginnings to building his Straits Cattle Trading empire, revealed his role as a community pillar, the cutthroat nature of his business, his sensational court case, and his eventual bankruptcy, culminating in the heart-wrenching tragedy of his son Yusuf’s suicide. These newspaper reports became the backbone of our storytelling, allowing us to vividly portray Moona Kader Sultan’s legacy with authenticity and depth.

Our writers and director drew extensively from these historical records to craft scenes that breathed life into the past. Newspaper articles not only shaped dialogue and timelines, but also the finer details of set design. For instance, archival photographs of 1930s street scenes inspired the bustling street market sequence, while images of Chettiars (a subgroup of the Tamil community often associated with moneylending) and kittangis (Tamil for “warehouse”) guided the creation of props and backdrops.3 The numerous articles documenting Yusuf’s tragic suicide informed a key scene where the characters’ raw emotions mirrored real-life accounts. This made the story deeply poignant and relatable, and heightened the emotional resonance for viewers. These meticulous touches brought the era to life, immersing viewers in the world of Karikal Mahal.

Image of a Chettiar used as a reference for the series. Here, the Chettiar, likely a moneylender, sits at his low wooden table in his kittangi, c.1950–70. Sharon Siddique, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Image of a Chettiar used as a reference for the series. Here, the Chettiar, likely a moneylender, sits at his low wooden table in his kittangi, c.1950–70. Sharon Siddique, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore. Reenactment of a young Moona Kader Sultan (sitting in the corner on the right) observing business dealings in the kittangi. Courtesy of Ochre Pictures.

Reenactment of a young Moona Kader Sultan (sitting in the corner on the right) observing business dealings in the kittangi. Courtesy of Ochre Pictures.Home of the Malayan Magic Circle

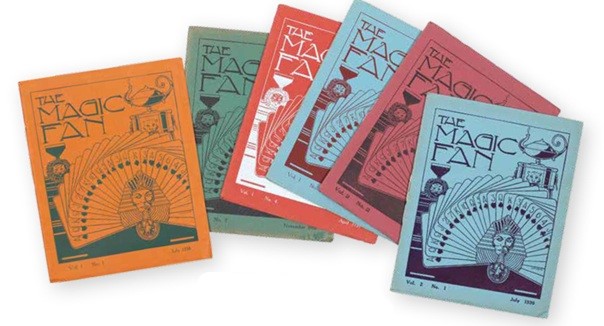

We also worked closely with Senior Librarian Gracie Lee from the National Library Singapore on the history of Singapore magic. Gracie generously bridged the gaps in our knowledge about the Malayan Magic Circle (MMC), sharing her deep understanding of its history and stories. Her expertise was instrumental in helping us uncover rare gems, including The Magic Fan – a magazine published by the MMC in the 1930s, which the library holds in its collection. This remarkable publication offers a fascinating glimpse into the MMC’s vibrant world. Its pages brim with accounts of the club’s lavish parties, members’ personal anecdotes, and even a dash of humour with funny quips and jokes.

Copies of The Magic Fan are held in the National Library Singapore’s collection.

Copies of The Magic Fan are held in the National Library Singapore’s collection.  Episode 2 features a reenactment of magician Tan Hock Chuan writing a column for The Magic Fan at the Malayan Magic Circle headquarters at Karikal Mahal. Courtesy of Ochre Pictures.

Episode 2 features a reenactment of magician Tan Hock Chuan writing a column for The Magic Fan at the Malayan Magic Circle headquarters at Karikal Mahal. Courtesy of Ochre Pictures.The magazines also featured step-by-step guides to tricks, performed and written by renowned local magicians such as Tan Hock Chuan and A.J. Braga. To add more authenticity to our reenactments, our cast learnt actual magic tricks from Singapore magician Enrico Varella, Vice-President of IBM Ring 115 (The Great Wong Ring), who also very kindly undertook the role of Braga in our series. From tricks to costumes, the combination of archival photos and newspaper archives provided the colourful backdrop for the MMC’s spectacular performances in the show.

Reenactment of The Great Wong’s Linking Rings act. Courtesy of Ochre Pictures.

Reenactment of The Great Wong’s Linking Rings act. Courtesy of Ochre Pictures. A.J. Braga’s exhilarating coffin act where he is straightjacketed and escapes from a sealed coffin. Courtesy of Ochre Pictures.

A.J. Braga’s exhilarating coffin act where he is straightjacketed and escapes from a sealed coffin. Courtesy of Ochre Pictures.House of Horror

In the final episode, the once opulent and palatial Karikal Mahal is now an internment camp following the Japanese Occupation of Singapore (1942–45). It was a challenge to find interviewees who could give first-hand accounts of Karikal Mahal as an internment camp, so the diary of Thomas Kitching, former Chief Surveyor of Singapore, formed the main narrative arc of this story. Kitching was among the civilians interned at Karikal Mahal; his diary was published in 2002 as the book Life and Death in Changi.

Re-enactment of Thomas Kitching writing in his diary while interned in Karikal Mahal. Courtesy of Ochre Pictures.

Re-enactment of Thomas Kitching writing in his diary while interned in Karikal Mahal. Courtesy of Ochre Pictures.By drawing on materials from NAS and NewspaperSG, we were able to enhance the experiences Kitching wrote about in his diary. While locating specific archival images to match his exact descriptions proved challenging, we managed to find similar visuals that effectively depicted scenes reminiscent of key moments, such as the atmosphere around Fullerton Building on the morning the Japanese forces invaded Singapore, or the journey of captured European civilians marching to Karikal Mahal. These elements helped convey the atmosphere and context of that time.

The vast amount of research we did for this series transformed the way we approach storytelling. Unearthing historical details allowed us to ground our narrative in authenticity while weaving in layers of depth and nuance. These discoveries helped us create scenes that felt true to their time yet resonated with universal emotions, making the characters’ journeys relatable and compelling. By blending the factual rigour of history with the emotional resonance of drama, we turned dry facts into human-centred stories that transported viewers to another time and place.

Re-enactment of civilian internees bowing to Japanese officers in Karikal Mahal. Courtesy of Ochre Pictures.

Re-enactment of civilian internees bowing to Japanese officers in Karikal Mahal. Courtesy of Ochre Pictures.For us, Karikal Mahal wasn’t just a setting; she was a living, breathing character. Her walls held the echoes of triumph, tragedy and mystery, and it was our responsibility to give her a voice – one that honoured Singapore’s layered history as our nation marks 60 years of independence this year. Storytelling like this invites audiences to connect with our past, offering them a window into the struggles and humanity of a different time. Karikal Mahal’s tale is just one of many waiting to be rediscovered and brought to life. The next time you go past an “old building”, stop and listen – what secrets and stories do their walls hold?

Rowena Loh is a Singapore-based director and producer whose works have reached audiences internationally. As a showrunner-director at Ochre Pictures, Rowena expands her directing and producing skills across various genres. Her notable television works include the award-winning series Last Madame: Sisters of the Night, which received multiple accolades, including Best Direction at the 2023 Asian Academy Creative Awards.

Rowena Loh is a Singapore-based director and producer whose works have reached audiences internationally. As a showrunner-director at Ochre Pictures, Rowena expands her directing and producing skills across various genres. Her notable television works include the award-winning series Last Madame: Sisters of the Night, which received multiple accolades, including Best Direction at the 2023 Asian Academy Creative Awards.Notes

-

William L. Gibson also wrote “Karikal Mahal: The Lost Palace of a Fallen Cattle King” (2020), “Unravelling the Mystery of Ubin’s German Girl Shrine” (2021) and “The Origin Stories of Keramat Kusu” (2023). ↩

-

William L. Gibson, “Karikal Mahal: The Lost Palace of a Fallen Cattle King,” BiblioAsia, published October 2020. ↩

-

Jaime Koh, “Chettiars,” Singapore Infopedia, published 10 December 2013. ↩