A Quiet Revolution: Women and Work in Industrialising Singapore

The role of women in Singapore’s nation-building efforts in the post-Independence years is sometimes overlooked. Janice Loo examines the impact that women have had on the nation’s development.

Women washing clothes at the kampung’s standpipe in the 1960s. Before Independence, women were mostly engaged in domestic activities. MITA collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Women washing clothes at the kampung’s standpipe in the 1960s. Before Independence, women were mostly engaged in domestic activities. MITA collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.It was 3 July 1959. Chooi Yong was working at the lathe machine when voices and footsteps along the corridor signaled their approach. She hurriedly smoothed her hair and straightened her apron just as the men entered the cabinet-making room. Incidentally, the first Cabinet of Singapore had been sworn in just a month earlier after the People’s Action Party (PAP) swept the 1959 general election. The newly minted Deputy Prime Minister Toh Chin Chye and the Minister for Education Yong Nyuk Lin were inspecting the Singapore Polytechnic, where first-year student Tan Chooi Yong was the only girl in the Engineering Department.

The next day, the Singapore Free Press reported the visit with an accompanying photograph of the education minister speaking to an intently listening Chooi Yong. “The new Singapore Government wants girls to put away their needlework, put on overalls and dungarees, and come forward to do practical work alongside the men,”1 urged the article’s opening line. The appeal for women to “end their worn-out role as ‘namby-pamby’2 people and join the workers”3 continued to resound in the years ahead as the island state, which catapulted to independence on 9 August 1965, struggled to find its economic footing.

Singapore’s founding fathers take pride of place in the canonical narrative of the country’s success. However, Singapore’s industrial takeoff in the late 1960s would not have been as brisk if not for its working mothers, wives and daughters, whose labour proved instrumental.4

At Home With Work

In 1957, on the eve of self-government, the female labour force participation rate (FLFPR) stood at a mere 21.6 percent, which meant that less than a quarter of the total female population aged 15 years and over was economically active.5 To put it plainly, just 1 out of every 5 women in that age group held a job or was unemployed and on the active lookout for work.

Nearly half of the female workforce was concentrated in the community, social and personal services sector, where most engaged in paid domestic work.6 Requiring little expense and minimal instruction or skills, working in the informal sector allowed women to earn extra income while managing their family responsibilities, as Chua Hui Neo revealed in an oral history interview about her life in the 1950s. “Women cannot go outside [to] work. What work can we do? No one will employ you. [My mother] had to do work for neighbours, do washing […] people sewed clothes, [and] she put the buttons.”7

For the majority who were economically inactive, life revolved around the home and family in conformance with the prevailing sex/gender division of labour. Recalling her adolescence spent in domestic drudgery, Chua summed up the situation: “All the time we had to stay at home, do the [housework]. The men go and work. Girls never worked.”8 It is important to note that being “economically inactive” did not necessarily mean that women idled; rather, the unpaid tasks performed, then as now, by women for the family – cooking, cleaning, child-minding and so on – was not treated as “real” work and thus consigned to invisibility. Certainly the nature of housework was more varied and laborious back then without modern conveniences such as running water and electricity, gas fires and home appliances.9

The situation soon changed. Between 1970 and 1980, the FLFPR rose impressively from 29.5 percent to 44.3 percent.10 By 1990, the figure had reached 53 percent, meaning that 1 out of every 2 women was in the labour force.11 Singapore’s “working woman” had emerged in the span of one generation amid rapid economic development and tremendous social change. With education and employment, she had created a “quiet revolution”12 that challenged the gender order.

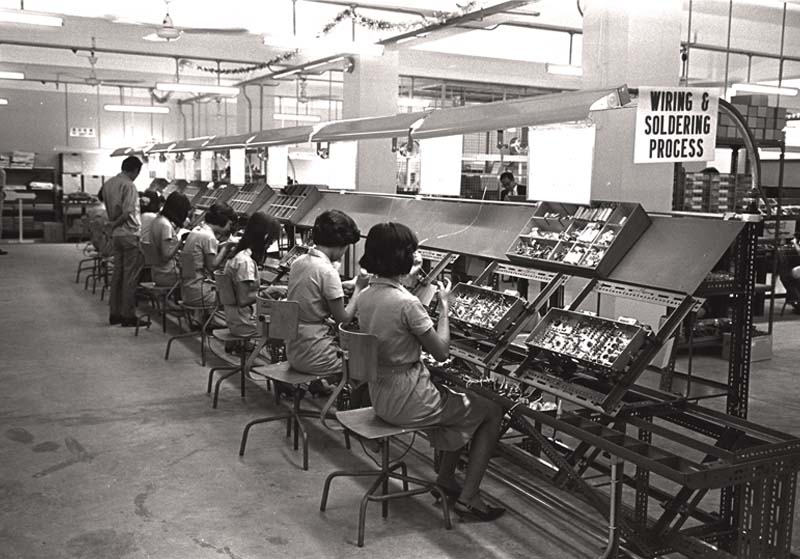

Women working in the factory of Roxy Electric Company Ltd in 1966. MITA collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Women working in the factory of Roxy Electric Company Ltd in 1966. MITA collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Women, Get Right to Work!

The story begins when the PAP, in its 1959 election manifesto, committed to the cause of women’s rights by pledging to encourage the participation of women in politics and administration; expand job opportunities for women and provide a context conducive to their employment; and grant equal rights to women in marriage and the family.13 This was an astute move to woo the female electorate, bearing in mind the implementation of compulsory voting and the growing momentum of the local women’s movement.14

Voted into power, the party soon fulfilled its election promise in 1961 with the enactment of the Women’s Charter by the Legislative Assembly, a watershed in the use of legislation to safeguard the status of women in matrimonial life.

The Women’s Charter was intended as a springboard for the eventual achievement of sex/gender equality on a societal level by first addressing the subjugated position of women in the patriarchal institutions of marriage and the family.15 Legal reform adopted this focus in response to the vigorous campaign mounted by the Singapore Council of Women to eliminate polygamy.16

Accordingly, the Charter included provisions for monogamy, legal equality and shared familial responsibilities of husband and wife for divorce, custody and maintenance, as well as the protection of women in cases of domestic abuse and sexual offences.17 More pertinently, the Charter enunciated, among other things, the rights of married women to hold and dispose of property, and engage in any trade or profession.18

The years 1959 to 1965 have thus been described as the period of establishing conditions – “lifting legal barriers”19 – for the greater social and economic participation of women. It was not until after Independence that the number of women in the labour force began to rise steadily with increased job opportunities brought by state-led industrialisation. However, as will be made evident later in this essay, the employment of women in Singapore was primarily a practical response to exigencies of the national and household economy, rather than a matter of their fundamental right to work.

Out of the Kitchen – Into the Production Line

“Now that the victories on the political front have been won, our activities and pioneer spirit have somewhat faded into significance and we have become complacent,”20 lamented Singapore’s first female Member of Parliament Chan Choy Siong in March 1968. A firm campaigner for women’s rights and a PAP member, Chan had played a critical role in pushing for the Women’s Charter. Their position in the home secured, it was time for women, according to Chan, to “come out of [their] domestic shells and stand shoulder to shoulder with the men in the field of economic reconstruction.”21

Separation from Malaysia in 1965 pitched Singapore into an economic quandary. Cut off from the anticipated Malaysian Common Market, the young republic was compelled to seek an alternative development strategy as its small domestic market and lack of natural resources precluded the import-substitution mode of industrialisation.22 Singapore thus embarked on an ambitious programme of industrialisation through labour-intensive, export-oriented manufacturing. Fortunately, the government‘s efforts to create a positive environment for foreign investment coincided with favourable conditions in the world economy, acting as a catalyst for the country’s industrial takeoff in the early decades of nationhood.23

Singapore’s first phase of industrialisation, spanning the years 1966 to 1978, triggered a period of steep increase in female labour force participation that extended into the 1980s. Women powered the employment and output growth in manufacturing which, barring the recession years of 1974–75 and 1982–83, was the fastest-growing sector of the economy.24 Between 1970 and 1980, the number of working women had more than doubled from 153,612 to 370,573.25 Manufacturing absorbed 46.9 percent of this increase and became the single largest sector for female employment.26

The entry of women into the workforce on such an unprecedented scale was attributed to factors shaping demand and supply in the labour market. Rapid economic growth, especially in the labour-intensive manufacturing sector, not only mopped up the problem of high unemployment but also generated more job opportunities for women.

Conversely, government policies on education, housing and family planning, coupled with official encouragement of women’s employment, spurred female labour participation in both intended and inadvertent ways. Age, marital status, educational attainment, and socioeconomic background determined the extent to which women have contributed and benefitted from economic development.

Workers at the factory of Tancho Corporation Limited at Little Road in 1967. Tancho was a sticky pomade that men used to style their hair. MITA collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Workers at the factory of Tancho Corporation Limited at Little Road in 1967. Tancho was a sticky pomade that men used to style their hair. MITA collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Singapore Needs (Wo)manpower

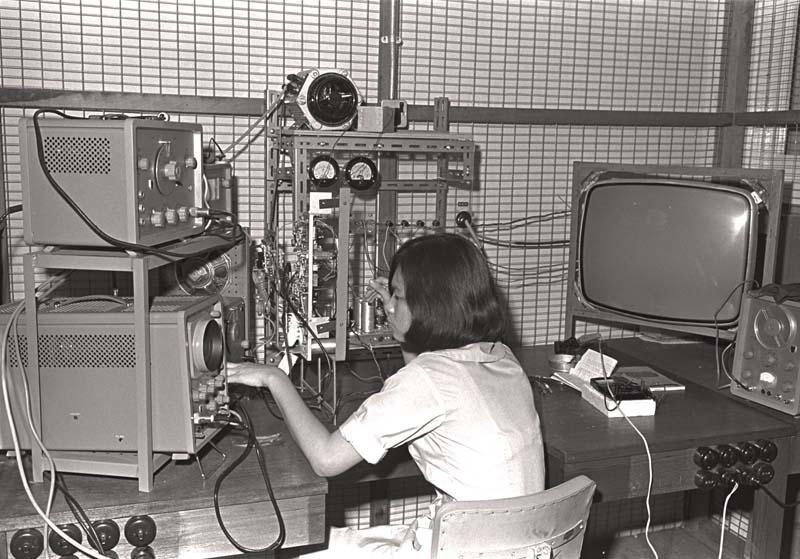

Qualities such as docility, diligence, attention to detail and patience for long hours of monotonous work have long been regarded as stereotypically “feminine” qualities that have made female labour the preferred choice in the electronics, textiles and garment industries.27 In addition, women were considered to be better suited than men for work in these industries owing to their physical traits – small hands and nimble fingers – coupled with experience with delicate manual tasks gained from sewing at home.28

Demand for female labour consequently accelerated as industrialisation proceeded apace. However, it should be noted that older, married women were at a disadvantage in light of the typical employers’ preference for young, single workers who were more easily trained and less encumbered by family commitments that could threaten productivity.29

The severe labour shortage prompted the government not only to relax regulations on the employment of temporary foreign workers, but also to mobilise the economically inactive female population.30 In general, single women in their early twenties had the highest rate of economic activity; this decreased with advancing age as many pulled out of work after marriage and childbirth to focus on family responsibilities.31 Only 1 in 7 married women, as compared with 1 in 3 single women, were economically active in 1970.32

A female worker at Setron Limited – which manufactured television sets – at Tanglin Halt in 1966. MITA collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A female worker at Setron Limited – which manufactured television sets – at Tanglin Halt in 1966. MITA collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.For a country that prizes human capital as its sole asset, the high proportion of economically inactive women represented a critically under-utilised resource. As such, housewives and young unmarried women who stayed home to help with domestic chores were identified by the state in 1971 as “the largest source for potential increase of the labour force.”33 Official measures taken to attract and retain women in the workforce included providing additional public childcare facilities, locating light-manufacturing industries within housing estates, and urging employers to offer part-time work arrangements.34

People’s Association Child Care Centre at Queen’s Street in 1985. Child care was and is a pressing concern of many working mothers. MITA collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

People’s Association Child Care Centre at Queen’s Street in 1985. Child care was and is a pressing concern of many working mothers. MITA collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Improvements in female educational attainment have given women access to more career options.35 The official view on the purpose of female education is best encapsulated in the words of then Minister for Law and National Development E. W. Barker, who in July 1968 said, “In providing girls the same educational opportunities as the boys, we [the government] expect the girls to be equally capable of contributing to the economic growth of our nation.”36 The impact that education had on transforming the pattern of female employment is expressed by Chua Hui Neo in an interview in 1995:

“If you got education, you can work. Before, if you have no education, what can you work? Like my mother she washed clothes for people. But now where got people want to wash clothes for others. Now no one. What for I work housework, how many… hundred. I might as well go and work in a factory. Morning I go, I wear nice clothes. I come back happy, one month I got how much and CPF [Central Provident Fund], everything. Now it is different. Now where to find a maid? Before, you get so many girls […] Now everyone, 15/16 years old they can go to the factory and work.”37

With education, women have been able to seize employment opportunities that offered regular hours, fringe benefits and better working conditions in the formal sector. Yet despite the near equal female to male ratio in the student population, the lack of technical training among women meant that they typically entered the manufacturing sector as low-pay, unskilled or semiskilled production workers with limited prospects and occupational mobility.38

At the same time, those who could not obtain employment in the industrial and commercial sectors due to age, education or family responsibilities had little alternative recourse.39

Changes on the Home Front

The costs of urban, high-rise living have rendered women’s employment a matter of financial necessity. In 1964, four years after the state public housing programme was launched, the New Lives in New Homes survey by the Persatuan Wanita Singapura found that respondents were of the unanimous opinion that life was costlier in Housing & Development Board (HDB) flats than in kampungs and pre-war tenements in the city centre.40 The additional expenditure was chiefly met by increased income through the wife’s efforts, for example, through making cakes for sale and taking in sewing jobs, or increases in the husband’s income as well as more careful budgeting and by working in small factories in the estate.41 At the time, about 20 percent of the population lived in HDB flats.42 By 1980, the figure had risen to 67.8 percent.43

Mass resettlement and home ownership propelled more women into the workforce to help cover daily expenses such as food and utilities, and the purchase of home appliances, furnishings, consumer goods and other trappings of the new lifestyle.44 When interviewed in the mid-1970s on her reasons for working, Ah Geok, who worked in an electronics assembly, replied, “Prices and inflation are so high nowadays that I have to work.”45 Faced with rising cash needs, the gainful employment of women became increasingly essential for the maintenance and improvement of family living standards.

In the meantime, the National Productivity Board, in its recommendations for increasing female participation in the labour force, mentioned that “domestic workload could be lightened considerably through the increased usage of domestic and other household appliances […] thus providing housewives with more time for leisure and work.”46 In fact, many of these appliances, including rice-cookers, refrigerators, electric irons and washing machines, were manufactured in Singapore for both export and domestic consumption.47 Women were in all likelihood the consumers of the products assembled by their very hands. This provides an added dimension to the understanding of women’s economic contributions; it was not by their labour alone that the industrial growth of Singapore was achieved.

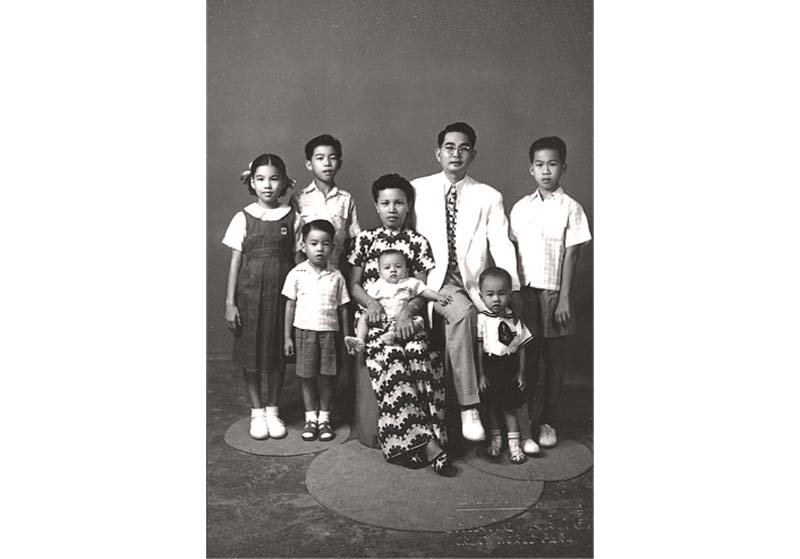

The adoption of the two-child family norm, brought about by an intensive national family planning campaign in 1972, reduced the time and effort required for childbearing, nursing and housework, thus facilitating the employment of women.48 Even so, the problem of childcare has been a major obstacle to the participation of women in the labour force after marriage.49

A studio photograph of a family of eight taken in 1940. Families were later encouraged to have a maximum of two children. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A studio photograph of a family of eight taken in 1940. Families were later encouraged to have a maximum of two children. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.By and large, working mothers relied on familial support for childcare and housework. For example, Sim Koo Kee left her two sons in the respective care of her mother and aunt while she put in a full day at work, and returned to fetch the children home each evening.50 Assistance from immediate family or relatives was regarded as a more reliable and affordable solution compared to hiring a domestic worker or using a childcare facility. Women were likely to sacrifice employment in the absence of childcare help, especially if it was better for a woman to be a full-time housewife than to work for low pay.51 Otherwise, working the night shift in the factory perhaps offered the only means of combining employment and motherhood for those who had trouble making substitute childcare arrangements.52 Women on the night shift would start work in the evening or late at night, after most child-minding and housework tasks were over, with intermittent rest during the day.53

On the whole, community networks proved to be the critical resource that facilitated women’s entry into the work force at a time when government social services for working mothers was in its nascence.54

A Women’s Work is Never Done

“Only a good woman can create a good family […] only a group of good families can make a good nation.”55 That was the role of women in nation-building as enunciated by Puan Noor Aishah, the wife of then Yang di-Pertuan Negara (Head of State) Inche Yusof Ishak in 1962. Her words hark back to a time when a woman’s place was in the home. However, as Singapore rapidly industrialised after Independence, it was imperative that women “become not just good housewives but economic assets as well.”56 More than a creature of legal reform and state policies, the “working woman” of Singapore came into being by dint of financial circumstance, initiative on the part of the individual woman, familial support and aspirations for upward social mobility.

The sex/gender division of labour has been breached but is by no means overturned as housework and childcare remain for the most part in female hands. 57 Women continue to juggle career and motherhood today. The quiet revolution is arguably still underway.

Janice Loo is an Associate Librarian with the National Library of Singapore. This is her second article on women in history following “Mrs Beeton in Malaya: Women, Cookbooks and the Makings of the Housewife” in the Oct–Dec 2013 issue of BiblioAsia.

REFERENCES

Arumainathan, P. (1973). Report on the census of population 1970 Singapore (Vol. 1). Singapore: Department of Statistics. (Call no.: RSING 312.095957 SIN)

‘Come out of your domestic shells’ call to women. (1968, March 14). The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Electrical goods find ready markets abroad. (1977, November 20). The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Ghim, P. (1994, March). The Singapore Council of Women and the women’s movement. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 25 (1), 112–140. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

Girls told: ‘Work beside men’. (1959, July 4). The Singapore Free Press, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Khoo, C.K. (1981). Census of population 1980 Singapore. Release No. 4, Economic characteristics. Singapore: Department of Statistics. (Call no.: RSING 312.095957 CEN)

Lai, A.E. (Interviewer). (1985, April 18). Oral history interview with Chua Hui Neo [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 001632/04/01, p. 8]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website.

Lim, L.Y.C. (1982). Women in the Singapore economy. Singapore: Chopmen Publishers. (Call no.: RSING 331.4095957 LIM)

Lim, L., & Pang, E.F. (1986). Trade, employment and industrialisation in Singapore. Geneva, Switzerland: International Labour Organisation. (Call no.: RSING 330.95957 LIM)

Lyons, L. (2004). A state of ambivalence: The feminist movement in Singapore. Leiden: Brill. (Call no.: RSING 305.42095957 LYO)

Men and women share the same views on night work. (1980, May 5). The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Ong, K.B. (1972, June 6). Housewife by day, worker by night. The Straits Times, p. 14. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Purushotam, N. (2003). Silent witnesses: The ‘woman’ in the photograph. In K.B. Chan & C.K. Tong (Eds.), Past times: A social history of Singapore (pp. 33–55). Singapore: Times Editions. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 PAS)

Purushotam, N. (2004). Women and knowledge/power: Notes on the Singaporean dilemma. In K.C. Ban, A. Pakir & C.K. Tong (Eds.), Imagining Singapore (pp. 328–364). Singapore: Eastern Universities Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 IMA)

Pwu, L.J., Campbell, K., & Chia-Chan, A. (1999). The 3 paradoxes: Working women in Singapore. Singapore: Association of Women for Action and Research. (Call no.: RSING 305.4 LEE)

Salaff, J.W. (1988). State and family in Singapore: Restructuring an industrial society. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. (Call no.: RSING 406.85095957 SAL)

Salaff, J.W., & Wong, A.K. (1984). Women’s work: Factory, family and social class in an industrialising order (pp. 189–214). In G.W. Jones (Ed.), Women in the urban and industrial workforce: Southeast and East Asia. Canberra: Australian National University. (Call no.: RSING 331.40949 WOM)

Saw, S.H. (2012). The population of Singapore. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. (Call no.: RSING 304.6095957 SAW)

Seow, P.L. (1965). Report of new life in new homes. Singapore: Persatuan Wanita Singapura. (Call no.: RCLOS 331.833 PER)

Singapore. Ministry of Social Affairs. Research Branch. (1984). Report on national survey on married women, their role in the family and society. Singapore: Research Branch, Ministry of Social Affairs. (Call no.: RSING 301.412095957 REP)

Singapore. Department of Statistics. (1996). Singapore, 1965–1995 statistical highlights: A review of 30 years’ development. Singapore: Department of Statistics, Ministry of Trade & Industry. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Singapore. Department of Statistics. (2014). Households & housing (table) key demographic indicators, 1970–2013. Retrieved from Singapore Department of Statistics website.

Toh, T.S. (1971). Increasing Singapore’s effective supply of labour. Singapore: National Productivity Centre. (Call no.: RCLOS 331.12095957 TOH)

Wee, C. (1980, May 25). Why housewives are opting for part-time work. The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Women here have important role, says Puan Aishah. (1962, April 27). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Wong, A.K. (1975). Women in modern Singapore, Singapore: Singapore University Education Press. (Call no.: RSING 301.412095957 WON)

Wong, A.K. (1979). Women’s status and changing family values. In E. Kuo & A.K. Wong (Eds.), The contemporary family in Singapore: Structure and change (pp. 40–61). Singapore: Singapore University Press. (Call no.: RSING 301.42095957 CON)

Wong, A.K. (1980). Economic development and women’s place: Women in Singapore. London: Change International Report. (Call no.: RSING 301.412095957 WON)

Wong, A.K. (1981, Winter). Planned development, social stratification, and the sexual division of labour in Singapore. Signs, 7 (2), 434–452. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

Wong, A.K., & Leong, W.K. (Eds.). (1993). Singapore women: Three decades of change. Singapore: Times Academic Press. (Call no.: RSING 305.42095957 SIN)

Wong, L.W. (1972, October 29). Quiet revolution in modern homes. The Straits Times, p. 22. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

NOTES

-

Girls told: ‘Work beside men’. (1959, July 4). The Singapore Free Press, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

A derogatory term to describe someone who is weak or indecisive, lacking in character, directness, or moral or emotional strength, or weakly sentimental. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press, 4 Jul 1959, p. 7. ↩

-

Lim, L.Y.C. (1982). Women in the Singapore economy (p. 25). Singapore: Chopmen Publishers. (Call no.: RSING 331.4095957 LIM) ↩

-

Saw, S.H. (2012). The population of Singapore (p. 276). Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. (Call no.: RSING 304.6095957 SAW) ↩

-

Arumainathan, P. (1973). Report on the census of population 1970 Singapore (Vol. 1, pp. 180, 182). Singapore: Department of Statistics. (Call no.: RSING 312.095957 SIN) ↩

-

Lai, A.E. (Interviewer). (1985, April 18). Oral history interview with Chua Hui Neo [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 001632/04/01, p. 8]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Oral history interview with Chua Hui Neo, 18 Apr 1985, p. 7. ↩

-

Purushotam, N. (2003). Silent witnesses: The ‘woman’ in the photograph (pp. 39–41). In K.B. Chan & C.K. Tong (Eds.), Past times: A social history of Singapore. Singapore: Times Editions. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 PAS) ↩

-

Singapore. Department of Statistics. (1996). Singapore, 1965–1995 statistical highlights: A review of 30 years’ development (p. 20). Singapore: Department of Statistics, Ministry of Trade & Industry. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Singapore. Department of Statistics, 1996, p. 20. ↩

-

Pwu, L.J., Campbell, K., & Chia-Chan, A. (1999). The 3 paradoxes: Working women in Singapore (p. 3). Singapore: Association of Women for Action and Research. (Call no.: RSING 305.4 LEE) ↩

-

People’s Action Party. (1959). The tasks ahead, PAP’s five year plan 1959–1964 (Part 1, p. 7). Singapore: The Party. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Ghim, P. (1994, March). The Singapore Council of Women and the women’s movement. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 25 (1), 112–140, p. 134. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Pwu, Campbell & Chia, 1999, p. 39. ↩

-

Lyons, L. (2004). A state of ambivalence: The feminist movement in Singapore (p. 27). Leiden: Brill. (Call no.: RSING 305.42095957 LYO) ↩

-

Wong, A.K., & Leong, W.K. (Eds.). (1993). Singapore women: Three decades of change (pp. 256–257). Singapore: Times Academic Press. (Call no.: RSING 305.42095957 SIN) ↩

-

Wong & Leong, 1993, pp. 256–257. ↩

-

Pwu, Campbell & Chia, 1999, p. 13. ↩

-

‘Come out of your domestic shells’ call to women. (1968, March 14). The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 14 Mar 1968, p. 5. ↩

-

Lim, L., & Pang, E.F. (1986). Trade, employment and industrialisation in Singapore (p. 17). Geneva, Switzerland: International Labour Organisation. (Call no.: RSING 330.95957 LIM) ↩

-

Lim & Pang, 1986, p. 5. ↩

-

Lim & Pang, 1986, p. 7. ↩

-

Khoo, C.K. (1981). Census of population 1980 Singapore. Release No. 4, Economic characteristics (p. 13). Singapore: Department of Statistics. (Call no.: RSING 312.095957 CEN) ↩

-

Lim, 1982, pp. 10–12; Wong, A.K. (1980). Economic development and women’s place: Women in Singapore (p. 10). London: Change International Report. (Call no.: RSING 301.412095957 WON) ↩

-

Wong, A.K. (1981, Winter). Planned development, social stratification, and the sexual division of labour in Singapore. Signs, 7 (2), 434–452, p. 441. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Toh, T.S. (1971). Increasing Singapore’s effective supply of labour (p. iii). Singapore: National Productivity Centre. (Call no.: RCLOS 331.12095957 TOH) ↩

-

Arumainathan, 1970, p. 65. ↩

-

Wong, A.K. (1975). Women in modern Singapore (p. 33). Singapore: Singapore University Education Press. (Call no.: RSING 301.412095957 WON) ↩

-

Girls urged to work as hard as the boys. (1968, July 27). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Lai, A.E. (Interviewer). (1985, April 18). Oral history interview with Chua Hui Neo [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 001632/04/04, p. 66]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Prevailing gender segregation in education where young females tended to pass up technical training, which was a stream dominated by males, in favour of academic or commercial studies. See Wong, winter 1981, p. 445. ↩

-

Wong, winter 1981, p. 442. ↩

-

Seow, P.L. (1965). Report of new life in new homes (p. 42). Singapore: Persatuan Wanita Singapura. (Call no.: RCLOS 331.833 PER) ↩

-

Singapore. Department of Statistics. (2014). Households & housing (table) key demographic indicators, 1970–2013. Retrieved from Singapore Department of Statistics website. ↩

-

Salaff, J.W. (1988). State and family in Singapore: Restructuring an industrial society (p. 30). Ithaca: Cornell University Press. (Call no.: RSING 406.85095957 SAL) ↩

-

Salaff, J.W., & Wong, A.K. (1984). Women’s work: Factory, family and social class in an industrialising order (pp. 189–214). In G.W. Jones (Ed.), Women in the urban and industrial workforce: Southeast and East Asia. Canberra: Australian National University. (Call no.: RSING 331.40949 WOM) ↩

-

Wong, L.W. (1972, October 29). Quiet revolution in modern homes. The Straits Times, p. 22; Electrical goods find ready markets abroad. (1977, November 20). The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Wong, A.K. (1979). Women’s status and changing family values (pp. 44–55). In E. Kuo & A.K. Wong (Eds.), The contemporary family in Singapore: Structure and change (pp. 40–61). Singapore: Singapore University Press. (Call no.: RSING 301.42095957 CON); Singapore. Ministry of Social Affairs. Research Branch. (1984). Report on national survey on married women, their role in the family and society (p. 138). Singapore: Research Branch, Ministry of Social Affairs. (Call no.: RSING 301.412095957 REP) ↩

-

Salaff & Wong, 1984, pp. 202–203. ↩

-

Salaff & Wong, 1984, pp. 200, 209, 213. ↩

-

Men and women share the same views on night work. (1980, May 5). The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Ong, K.B. (1972, June 6). Housewife by day, worker by night. The Straits Times, p. 14; Wee, C. (1980, May 25). Why housewives are opting for part-time work. The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Salaff & Wong, 1984, p. 213. ↩

-

Women here have important role, says Puan Aishah. (1962, April 27). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 27 Jul 1968, p. 4. ↩

-

Purushotam, N. (2004). Women and knowledge/power: Notes on the Singaporean dilemma (p. 329). In K.C. Ban, A. Pakir & C.K. Tong (Eds.), Imagining Singapore (pp. 328–364). Singapore: Eastern Universities Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 IMA) ↩