The Pulse of Malayan Literature

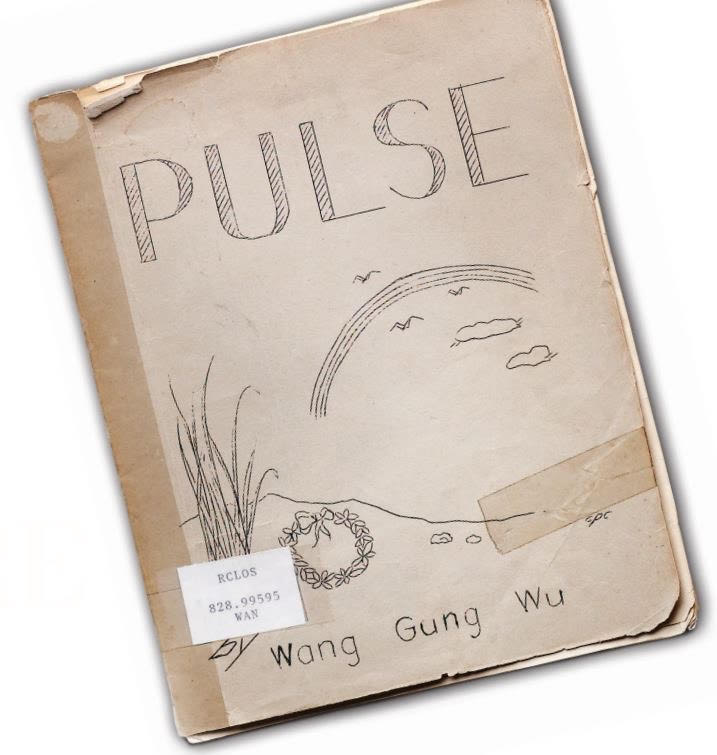

Title: Pulse

Author: Wang Gungwu (1930–)

Year published: 1950

Publisher: Beda Lim (Singapore)

Language: English

Type: Book; 16 pages

Call no.: RCLOS 828.99595 WAN

Accession nos.: B02863093I; B29230019D

Donated by: Professor Wang Gungwu

In the early 1950s, two young Malayan undergraduates, Wang Gungwu and Beda Lim, bonded over their shared love for English poetry. They spent hours poring over the classic literary works of Shakespeare, W. H. Auden and T. S. Eliot, and in the process were inspired to create their own unique brand of literature.1

Just 19 years old at the time, Wang was inspired to create literary works that were distinctly Malayan in character. Pulse,the first known collection of English poems by a Malayan, was the culmination of his early literary efforts. Lim helped Wang publish his maiden poetry collection,2 and the year of its publication, 1950, has been hailed by prominent Singaporean writers like Edwin Thumboo as the defining moment Singaporean/Malayan poetry took root.3

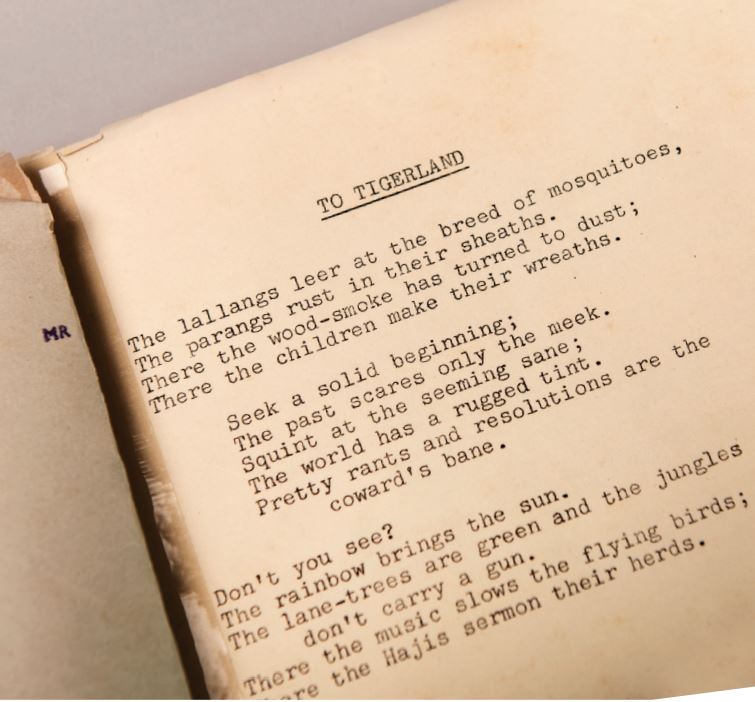

Reflecting its origins as an amateur varsity production, Pulse – a modest 16-page booklet – is stapled together with a cover that is adorned with a hand-drawn illustration of the first poem, “To Tigerland”. The cover design depicts a floral wreath lying on the ground beside sheaves of lallang and is framed by clouds, birds and a rainbow. It contains 12 poems on various topics written in a variety of styles and forms, ranging from free verse to rhymed metrical stanzas.4

From a literary perspective, Pulse is the earliest attempt by a writer to avoid the imitation of English verse, and to create a new and authentic literary voice. The sense of place in Wang’s poems is distinctly Malayan for the most part, for example in the poem “Three Faces of Night” he writes:

The crowds wait their share of the steaming fun

At the kuey-teow stalls of the kerosene glare;…5

In “Pulse”, the imagery and aesthetics draw references from English, Malay, Chinese and Malayan culture:

Trouser-wearing women

Worm among saris, sarongs

colourfully checked;

Baju biru full of tailings,

And sams unhooked at the neck;…6

Wang also uses a mix of English and Malay in his poems. This is seen in the poem “Ahmad”:

Allah has been kind;

Orang puteh has been kind.

Only yesterday his brother said,

“Can get lagi satu wife lah!”7

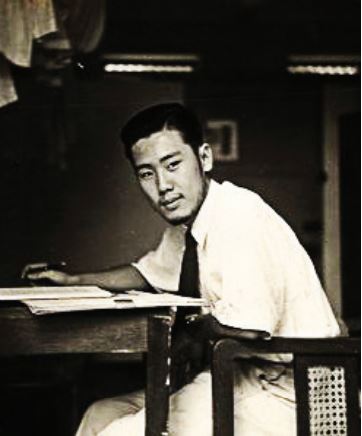

Wang was born in Surabaya, Indonesia, in 1930, but grew up in Ipoh, Malaysia. He enrolled in the University of Malaya in Singapore in 1949, where he studied English literature, history and economics.8 Being proficient in Malay, Chinese and English, Wang was able to reflect the plurality of Malayan society in his works. Inspired by the sweeping political changes and nationalistic fervour of his era, Wang and other fledgling writers of the time wanted to create a form of poetry that was unique to the region. The outcome was the unique hybrid form dubbed as “Engmalchin” (English, Malay, Chinese), which attempted to infuse local elements into English poems.9

Engmalchin, however, was a failed literary experiment. The 1955 issue of New Cauldron explained: “We have assessed previous undergraduate attempts at the creation of an artificial language by an arbitrary mixture of phrases drawn from the existing languages spoken in Malaya. We regret to say that this language, Engmalchin, as its advocates termed it, is a failure if only because of its self-conscious artificiality and the failure of its ‘sires’ to understand that language can never be created by edict.”10

Despite the failure of Engmalchin as a literary form, Pulse, nonetheless, serves as the standard reference for the study of Singaporean literature in English11 – literature born of the aspirations of young Anglophone writers raised in an era of decolonisation and rising nationalism.12

Today, Wang Gungwu is better known as a distinguished historian and scholar on the Chinese diaspora; less is known about his literary forays during his varsity days and their significance to the early development of Singaporean literature.13 When Pulse was published, Wang saw his work receive critical acclaim in the Singapore Free Press and The Straits Times.14 He continued writing poetry and penning short stories – some under the pseudonym Awang Kedua – which were published in student journals such as The New Cauldron,The Malayan Undergrad and The Compact: A Selection of University of Malaya Short Stories, 1953–1959.15

Wang stopped writing in the early 1960s16 after graduating with a Doctorate in History at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London. He became a noted historian, assuming roles as University Professor at the National University of Singapore, Chairman of the East Asian Institute and Emeritus Professor at the Australian National University.17 Wang‘s friendship with Beda Lim endured after graduation. Lim was the Chief Librarian at the University of Malaya Library from 1965 to 1980. He died in 1999 at the age of 73.18

– Written by Gracie Lee

NOTES

-

Yeo, R. (Interviewer). (2008, February 26). An interview with Wang Gungwu (in the mid 1980s). Retrieved from S/PORES website. ↩

-

Holden, P. (2002). Interrogating diaspora: Wang Gungwu’s Pulse. ARIEL: A Review of International English Literature, 33 (3–4), 114. Retrieved from Synergies Canada website; Tan, T. S. (1950, May 13). A book of poems comes from a Malayan’s pen. The Singapore Free Press, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Koh, T. A. (Ed.). (2008). Singapore literature in English: An annotated bibliography (p. 146). Singapore: National Library Board Singapore and Centre for Liberal Arts and Social Sciences, Nanyang Technological University. Call no.: RSING 016.8208 SIN-[LIB]. ↩

-

Patke, R. S., & Holden, P. (2010). Malaysian and Singaporean writing to 1965. In The Routledge concise history of Southeast Asian writing in English (p. 51). London: New York: Routledge. Call no.: RSING 895.9 PAT. ↩

-

Wang, G. (1950). Pulse (pp. 14–15). Singapore: Beda Lim. Call no.: RCLOS 828.99595 WAN; Lim, S. (1989). The English-language writer in Singapore. In Sandhu, K. S., & Wheatley, P. (Eds.). Management of success: The moulding of modern Singapore (pp. 523–551). Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. Call no.: RSING 959.57 MAN-[HIS]. ↩

-

Asad, L. (2010). (Ed.). Wang Gungwu: Junzi: Scholar-gentleman in conversation with Asad-ul Iqbal Latif (p. 1). Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. Call no.: RSING 959.007202 WAN. ↩

-

Holden, P. (2008, January 10). Introduction to “Learning Me Your Language”. Retrieved from S/PORES website. ↩

-

Vackey, T. (1955, Michaelmas Term). Editorial. The New Cauldron, 4. ↩

-

Holden, 2002, pp. 105–129. ↩

-

Holden, P. (2002, July 25). Introduction. Retrieved from Post Colonial Web website; Wong P. N. (2009). In the beginnings: university verse in the first decade of the University of Malaya. In Mohammad A. Quayum, P. N. Wong & E. Thumboo, E. (Eds.). Sharing borders: Studies in contemporary Singaporean-Malaysian literature (pp. 78–82). Singapore: National Library Board in partnership with the National Arts Council. Call no.: RSING S820.9 SHA; Talib, I. S. (2002). The development of Singaporean literature in English. In Mohammad A. Quayum, & P. C. Wicks. (Eds.). Singaporean literature in English: A critical reader (p. 5). Malaysia: Universiti Putra Malaysia Press. Call no.: RSING 820.995957 SIN. ↩

-

Holden, 10 Jan 2008. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press, 13 May 1950, p. 3; D.E.S. (1950, May 31). East & west have met. The Straits Times, p. 10; Wang, G. W. (1950, May 18). Faces of night. The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Holden, 2002, p. 114; Brewster, A. (1989). Towards a semiotic of post-colonial discourse: University writing in Singapore and Malaysia (p. 7). Singapore: Heinemann Asia for Centre for Advanced Studies. Call no.: RSING 808.1 BRE; Patke & Holden, 2010, p. 51; Hochstadt, H. (Ed.). (1959).The compact: A selection of University of Malaya short stories, 1953–1959. Singapore: Raffles Society, University of Malaya in Singapore. Call no.: RCLOS S823 COM-[RFL] ↩

-

Patke & Holden, 2010, p. 51. ↩

-

Yeo, 26 Feb 2008; Nordin, M. (1999, April 2). Farewell my friend, great reader of books. New Straits Times. Retrieved from Factiva via NLB’s eResources website. ↩