Collecting the Scattered Remains: The Raffles Library and Museum

Gracie Lee charts the history of the Raffles Library – precursor of the National Library – and its enigmatically named “Q” Collection.

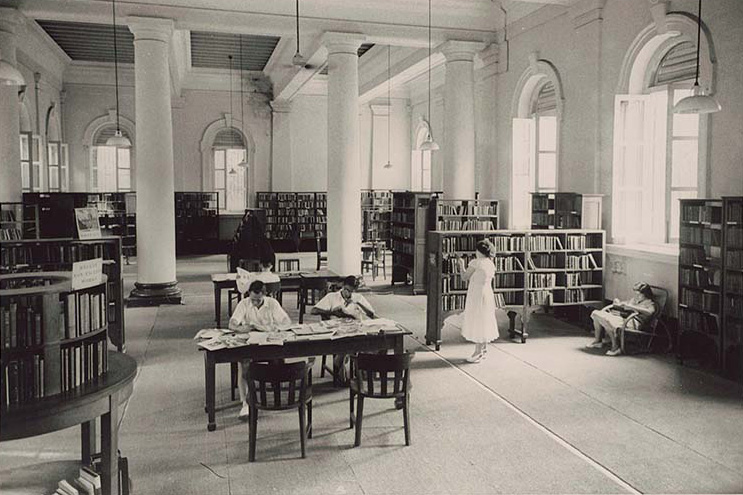

The library section of the Raffles Library and Museum, circa 1950s. The building on Stamford Road (which is today the National Museum of Singapore) housed the library on the ground floor and the museum on the first floor. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

The library section of the Raffles Library and Museum, circa 1950s. The building on Stamford Road (which is today the National Museum of Singapore) housed the library on the ground floor and the museum on the first floor. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.“The Raffles Library and Museum… is well worth a visit, for the Library is one of the largest and most comprehensive in the East, and the Museum, which is daily enriched by zoological, mineralogical, ethnological and archaeological collections from the Peninsula and the Archipelago, promises to be, in time, one of the finest exhibitions of its kind in Asia.”1

– George Murray Reith in Handbook to Singapore (1892)

The National Library began life in 1837 as a school library of the Singapore Free School (precursor of the Raffles Institution). The idea of a library was first conceived in 1819 when Stamford Raffles drew up his vision of a native college that would educate the sons of the Malay elite and employees of the East India Company. Part of his plan was a library that would “… collect the scattered literature and traditions of the country, with whatever may illustrate their laws and customs”.

Raffles believed that “by collecting the scattered remains of the literature of these countries, by calling forth the literary spirit of the people and awakening its dormant energies… will our stations not only become the centres of commerce and its luxuries, but of refinement and the liberal arts”.2

However, the vision of a library that would spur intellectual inquiry in this region would only be realised years later in 1874 with the establishment of the Raffles Library and Museum.

The First Library in Singapore

After its founding in 1823, work on the Singapore Institution progressed in fits and starts until 1836 when an effort was made to revive the educational institution in memory of Raffles. Restoration to the building on Bras Basah Road was completed in 1837, and in a fortuitous confluence of events, the Singapore Free School, which taught elementary classes at High Street since 1834 – in premises that had fallen into disrepair – was invited to move into the building meant for the Singapore Institution.

The library at the Singapore Free School was first mentioned in the third school annual report in April 1837. In response to its appeal for suitable educational materials, the school had received donations of Malay school books and tracts as well as English grammar books and dictionaries from missionaries and supporters. Some of these gifts were channelled into what became a well-used school library.

In December 1837, the Singapore Free School and the library moved into the Singapore Institution building. (The Singapore Free School later amalgamated with the Singapore Institution in 1838 to form the Singapore Institution Free School.) The library had a modest collection of 392 volumes of mostly elementary readers and primers, and was open to all for perusal. Borrowing privileges were, however, reserved for teachers, students and subscribers.

The First “Public Library” in Singapore

The school library became popular with residents in the fledgling years of the settlement when entertainment and news from Europe were limited. Soon, calls were made for the establishment of a “public library” that would serve the community beyond school hours. Taking heed, the Singapore Library was officially opened on 22 January 1845.

The library operated from the north wing of the building with a core collection that was moved from the school library. Among the notable users of the Singapore Library was the renowned naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace. However, the Singapore Library was not a public library by any modern definition. Though aimed at the wider community, it was not supported by public funds, nor was it free. It was in fact a private enterprise managed, funded and opened to shareholders and subscribers only.

Although, the management committee was understandably concerned with procuring popular reading material from London in order to sustain readership and stay profitable, it recognised the library’s place in Asia. According to the sixth report of the Singapore Library, “any valuable new publications on India, China, or other Eastern British Settlement” would be given “first consideration on all occasions”3 in the selection of new titles.

The library also benefited from prominent residents such as William Henry Macleod Read, Alexander Laurie Johnston and William Napier who generously offered Asian titles to its collection. Today, several titles from the Singapore Library remain and have been preserved in the National Library’s Rare Materials Collection. These include George Finlayson’s The Mission to Siam, and Hue the Capital of Cochin China (1826), The Private Letters of Sir James Brooke (1853) and The Private Journal of the Marquess of Hastings (1858). The earliest extant copy of the Singapore Library catalogue, published in 1860, serves as a record of the reading tastes of that period.

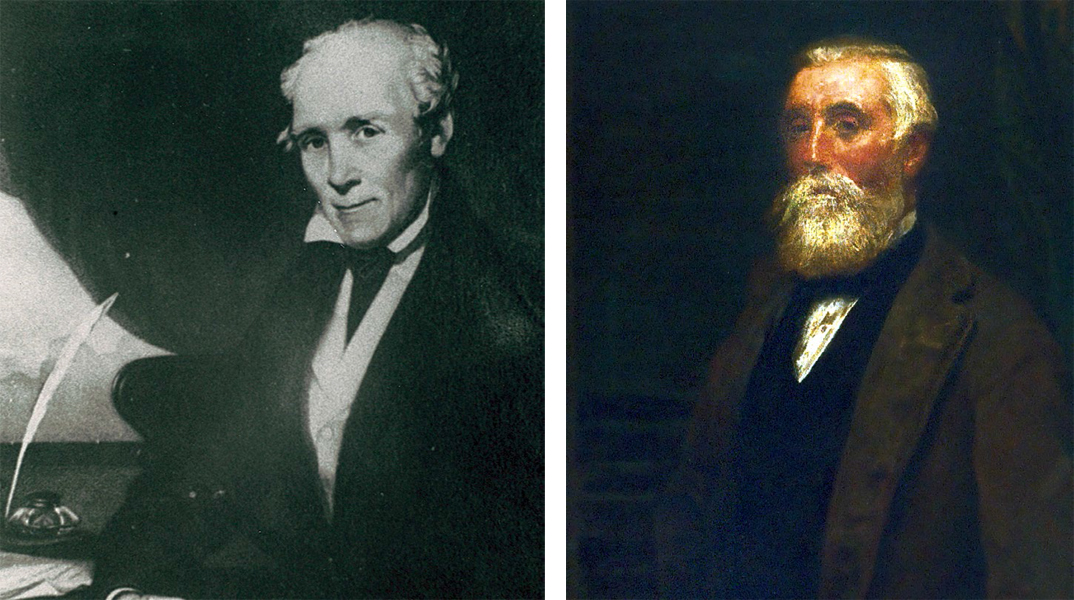

Portraits of Alexander Laurie Johnston (left) and William Henry Macleod Read (right). Both pioneers of Singapore generously donated Asian titles to the Singapore Library in the 1850s. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

Portraits of Alexander Laurie Johnston (left) and William Henry Macleod Read (right). Both pioneers of Singapore generously donated Asian titles to the Singapore Library in the 1850s. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.Establishment of the Raffles Library and Museum

Although mention of a museum as part of the library had surfaced as early as 1823 by the missionary Robert Morrison, co-founder of the Singapore Institution, this only took root in 1849 when the Temenggong of Johor presented the library with two gold coins of probable Achehnese origins. With this donation, the library committee resolved that the coins would form the “nucleus of a museum, tending to the elucidation of Malayan history” and that the public museum named “The Singapore Museum” would “illustrate the general history and archaeology of Singapore and the Eastern Archipelago”.4 Thus began the link between the library and museum that would last 106 years until their separation in 1955.

In May 1873, public interest in the colonial products displayed at London’s Exhibition Building prompted the Legislative Council of the Straits Settlements to lobby for a similar permanent exhibition in Singapore that would showcase commercial products from the Straits Settlements as well as artefacts on the ethnology, antiquities, natural history and geology of the region. Some seven months later, the matter was revisited, but this time the call was for a museum showcasing objects of interest on natural history.

The proposal was welcomed by the new governor of the Straits Settlements, Andrew Clarke, who suggested that a public library be combined with the museum. The committee of the new library and museum concluded that it would be expedient for the government to take over the operations of the new entity. So, on 1 July 1874, the Singapore Library and its collection of 3,000 books were transferred to the newly formed Raffles Library and Museum, which officially took on the name on 16 July that year.

Origins of the Malayan “Q” Collection

The new Raffles Library and Museum, now located on the top floors of the Town Hall (today’s Victoria Theatre), opened its doors on 14 September 1874. It comprised a Reference Library and a Reading Room that provided free access to the public, and a Lending Library for subscribers. The creation of a Reference Library marked the formal beginnings of a Malayan collection.

The Town Hall (present-day Victoria Theatre) in an 1870s photo. The Raffles Library and Museum, located on the top floors of the building, opened on 14 September 1874. It comprised a Reference Library, a Reading Room and a Lending Library. Lee Kip Lin Collection. All rights reserved. Lee Kip Lin and National Library Board, Singapore 2009.

The Town Hall (present-day Victoria Theatre) in an 1870s photo. The Raffles Library and Museum, located on the top floors of the building, opened on 14 September 1874. It comprised a Reference Library, a Reading Room and a Lending Library. Lee Kip Lin Collection. All rights reserved. Lee Kip Lin and National Library Board, Singapore 2009.The objective of the Reference Library was “to collect valuable works relating to the Straits Settlements and surrounding countries”5 as well as general works on the sciences and the arts. With its fast expanding collection, the library ran out of space in just two years and had to be relocated to temporary premises at the Raffles Institution (the Singapore Institution had been renamed in honour of Raffles around 1868) while a new and bigger building was constructed.

The move back to the Raffles Institution building in 1876 presented the library with an opportunity to re-catalogue its books. Departing from the six-genre arrangement, the books were now organised into 24 subjects, each represented by a letter of the English alphabet. The letter “Q”, inexplicably, was the shelf mark for “Works on Singapore, the Straits Settlements and the Eastern Archipelago”.

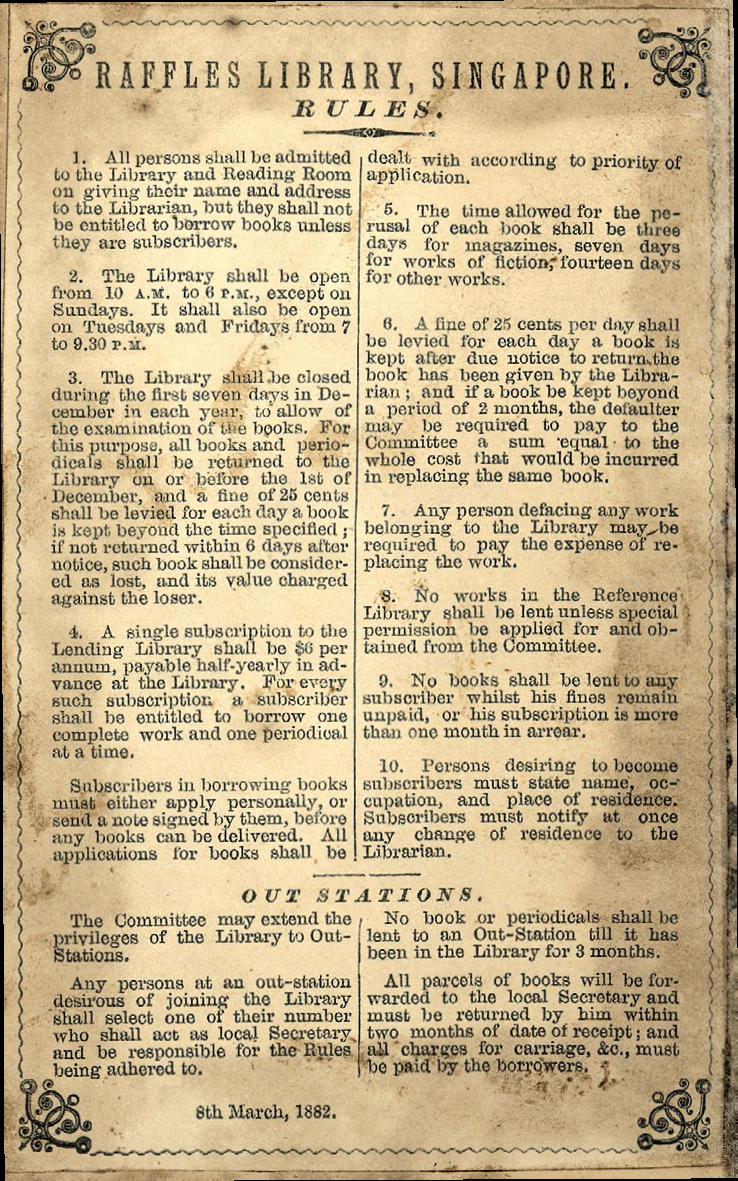

Rules of the Raffles Library, 8 March 1882. The National Library’s Rare Materials Collection.

Rules of the Raffles Library, 8 March 1882. The National Library’s Rare Materials Collection.With the re-organisation, the first general catalogue and synoptical index of the Raffles Library was published. This was followed by possibly the first bibliography on Malayan works compiled by the librarian and curator Nicholas Belfield Dennys. Published in 1880, the bibliography listed works in the Raffles Library as well as holdings from overseas sources such as the British Museum Library (today’s British Library), the Royal Asiatic Society library, the William Marsden collection at King’s College, and publishers such as Trübner and Company and Bernard Quaritch. Dennys had delineated Malaya as the area bounded by the Malayan/Siamese border, Borneo, the Philippine islands, New Guinea, Java and Sumatra. In all, he listed nearly 400 titles in his catalogue.

In 1880, the “Q” Collection received a much needed boost when the library acquired the philological library of James Richardson Logan. Logan was the editor of the scholarly Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia. His collection consisted of 1,250 volumes of “nearly all existing works on the languages of Malaya, Melanesia, etc.; some of the volumes being of high value”.6 To aid researchers, a catalogue of the Logan Library was published the next year.

Owing to its identity as a library and museum, the development of the library’s collection was significantly influenced by the work of the museum. Scientific publications concerning the flora and fauna of the region, such as Pieter Bleeker’s multi-volume tome Atlas Ichthyologique des Indes Orientales Neerlandaises (1862–78) on the fishes of the East Indies, were acquired with the aim of building up the library and museum as a research centre for visiting naturalists.

Growth of the “Q” Collection

On 12 October 1887, the new Raffles Library and Museum building on Stamford Road was finally inaugurated on the occasion of Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee. The striking neoclassical structure with its 90-foot-high dome initially housed the library on the ground floor and the museum on the first floor. Today, the building is home to the National Museum of Singapore.

A postcard reproduction of the Raffles Library and Museum on Stamford Road with its neoclassical architecture and 90-foot-high dome, 1900s. Today, the building is home to the National Museum of Singapore. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A postcard reproduction of the Raffles Library and Museum on Stamford Road with its neoclassical architecture and 90-foot-high dome, 1900s. Today, the building is home to the National Museum of Singapore. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.The move was timely as the library had begun receiving the first Straits Settlements publications forwarded under the Book Registration Ordinance of 1886 – the precursor of the Legal Deposit function that is in place today. The new law required three copies of every book printed in the colony to be deposited with the colonial government. These deposited materials were, however, kept distinct from the rest of the collections. Thanks to the generous space in the new building and subsequent extensions made in 1906, 1916 and 1926, much headway was made with the Malayan Collection.

In 1897, the library made another important acquisition. The Rost Collection, part of the private library of the late Dr Reinhold Rost, Librarian of the India Office, London, was acquired from the executors of his estate. The collection comprised 970 volumes on the philology, geography and ethnology of the Malay Archipelago. The philology section, which formed the bulk of the corpus, contained works on over 70 different languages and dialects of the East, with the Malayan and Javanese languages being most represented. A catalogue following an arrangement similar to the one done on the Logan Collection earlier was published to facilitate access to the collection. The same year, special efforts were made to improve the library’s zoological collection, particularly in the area of marine zoology, which it woefully lacked. A sum of 500 Straits dollars was set aside for the procurement of these works. It was also decided then that if the library and museum were ever to separate, these works would remain with the museum, providing an early hint that it had become untenable to administer the two institutions as one.

Progress was also made in the area of cataloguing and collection maintenance. In 1898, the backlog of materials on the Straits Settlements that had been lying neglected for years were finally organised; a number of important discoveries were made in the process, including a near complete set of the Straits Times Directory from 1846. The commercial directory, known colloquially as Buku Merah (Red Book) in reference to its red cover, is an important historical source on early businesses and European residents in Singapore.7 To protect the collection from frequent handling and insect damage, book-binding and fumigation using a toxic solution of mercuric chloride, carbonic acid and methylated spirit were carried out.

Donations continued to be an important way of expanding the collection, and several valuable ones from institutional and private donors were received. The government and the Straits Philosophical Society were faithful donors, ensuring that the library had a comprehensive set of official papers and the Blue Books – annual statistical reports bound in blue covers – and the society’s journal, Transactions of the Straits Philosophical Society. The Singapore Chamber of Commerce was also a long-time supporter – faithfully donating copies of its reports every year, and in 1909, its archives of Singapore and Penang newspapers. The donation was gratefully received as it filled gaps in the library’s collection of The Straits Times for the years 1874–86. The library also has the first issue of The Straits Times dated 15 July 1845 that was displayed at the ArtScience Museum from 17 July to 4 October 2015 in an exhibition celebrating the newspaper’s 170th anniversary.

In 1923, the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, which had been operating its private library in the library building since 1893, made a “permanent loan” of its collection of 2,000 books on the ethnology, flora, fauna, geology and geography of the Malay world to the Raffles Library. The valuable books were catalogued and merged with the rest of the collection, thus strengthening the library’s standing as a centre for Malayan scholarship. One such prized title is the 1849 lithographed edition of the Hikayat Abdullah.8

Besides institutional donors, the library also benefited from the generosity of private donors. Examples of donated items from this period, complete with the original gift plates, include The Hindu Ruins in the Plain of Parambanan (1901) presented by William Nanson, partner of the legal firm Rodyk & Davidson and John Brooke Scrivenor’s collection of his geological papers on Singapore and Malaya (1908).

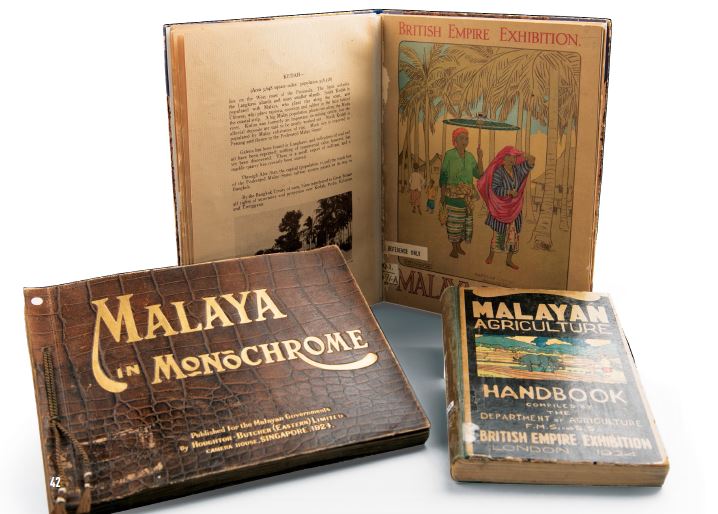

Important historical events also provided opportunities for expanding the collection. Of note was the British Empire Exhibition, held in London in 1924 and 1925. Regarded as the largest trade fair ever staged, the exhibition showcased agricultural, industrial and cultural displays from the far-flung corners of the British Empire. The occasion led to the publication of several books on Malaya: Illustrated Guide to British Malaya (1924); Malaya in Monochrome (1924); Malayan Agriculture: Handbook (1924); Report on the Malaya Pavilion (1926); and 18 pamphlets on topics such as the agricultural crops of Malaya, Malay arts and crafts, and labour in Malaya.

Illustrated Guide to British Malaya (standing upright), Malayan Agriculture: Handbook and Malaya in Monochrome were three publications produced in 1924 in conjunction with the British Empire Exhibition held in London. The National Library’s Rare Materials Collection.

Illustrated Guide to British Malaya (standing upright), Malayan Agriculture: Handbook and Malaya in Monochrome were three publications produced in 1924 in conjunction with the British Empire Exhibition held in London. The National Library’s Rare Materials Collection.By 1925, the ‘Q’ collection had grown to 897 volumes, on top of the Logan and Rost collections. The increase necessitated a revision of the library’s in-house classification scheme. With advice from leading British orientalist Richard Olaf Winstedt, the shelf mark “Q” was divided into eight geographical regions, beginning with Q10 for books on the Malay Archipelago and ending with Q18 for New Guinea. The “Q” collection comprised principally works on the Malay Archipelago, extending up to Formosa (present-day Taiwan) but excluded Indochina or what is known today as mainland Southeast Asia. The latter as a concept only came to the fore after World War II. In 1932, “Q11: Works on the British Malaya” was further divided by the different states of the Malay Peninsula.

The year 1925 also marked the first time that the term “Malaysian Collection” was used by the library. In the Descriptive Catalogue of the Books Relating to Malaysia in the Raffles Museum & Library Singapore, published in 1941, Malaysia is defined as “all land on the Sunda Shelf which includes the Malay Peninsula south of Lat. 10ºN, Sumatra, Borneo, Java and all the adjacent small islands west of Wallace’s Line”.9 Wallace’s Line refers to an imaginary boundary separating the ecozones of the Indo-Malayan and the Austro-Malayan Regions proposed by Alfred Wallace in 1859. This bibliography, which contains 1,787 titles, presents the most detailed description of the composition of the Malayan Collection prior to World War II.

Wallace’s Line is depicted in red on this map of the Malay Archipelago from Wallace’s paper “On the Physical Geography of the Malay Archipelago” (1863). His concept of a discontinuity in fauna between Asia and Australasia influenced the collecting scope of the Malayan Collection. The National Library’s Rare Materials Collection.

Wallace’s Line is depicted in red on this map of the Malay Archipelago from Wallace’s paper “On the Physical Geography of the Malay Archipelago” (1863). His concept of a discontinuity in fauna between Asia and Australasia influenced the collecting scope of the Malayan Collection. The National Library’s Rare Materials Collection.The map collection of the library began in 1932 when all its maps and charts were collated and housed in a single section. The collection grew in importance in 1934 when the library commissioned a study of the early maps and charts relating to the Malay Peninsula found in the libraries of overseas entities such as the British Museum, Royal Geographical Society, School of Oriental Studies and the Royal Asiatic Society. The result was four portfolios of 208 facsimiles that documented Malayan cartography from pre-1600 to 1879. As Malayan cartography had hitherto been a little explored subject, the survey provided a good knowledge base of the types of maps on Malaya and their availability. A catalogue titled Mills Collection of Historical Maps of Malaya, named after its compiler J. V. Mills, was published in 1937. Today, the Mills Collection serves as a useful reference for researchers who do not have ready access to the original maps in European libraries. While the maps are uncoloured copies, they are of sufficient quality to be used as a study aid.10

In 1932, a legal section comprising the laws, enactments and ordinances of the Straits Settlements and Malay States, as well as government gazettes and official publications, was formed. Six years later in 1938, the first archivist, Tan Soo Chye, was hired to organise the official records which had been transferred from the colonial secretariat, laying the foundation for today’s National Archives. Work on the archives proceeded smoothly and a year later in 1939, the Index to the Straits Settlements Records 1800–1867 was produced. The index is popularly known today as the Tan Soo Chye Index, named after its compiler.

The War Years: Syonan Tosyokan

The Japanese Occupation of 1942–45 brought untold suffering to Singapore as well as the destruction of printed heritage. The official papers of the Straits Settlements were thrown out and reportedly used in markets to wrap fish, meat and vegetables. Fortunately, the library, renamed Syonan Tosyokan, escaped relatively unscathed. While the building suffered from slight shelling and some books destroyed, looted or siphoned off to Tokyo, the collection stayed largely intact. Through the swift action of a few British and Japanese staff, the library was sealed off just three days after the fall of Singapore.

The Japanese researchers, attached to the library and museum (the museum was renamed Syonan Hakubutsukan), were also sympathetic to the work of the institution and protected it from being ravaged by the Japanese military. Through the ingenuity of British and local staff, valuable books were also kept away from sight, hidden among unsorted piles of less important books. Nonetheless, the adverse storage conditions of the Occupation wreaked irreparable damage to part of the newspaper collection and the manuscript documents of the archives.

Japanese staff of the Syonan Hakubutsukan (Syonan Museum), July 1943. Photo donated by Mdm Michiyo Haneda. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

Japanese staff of the Syonan Hakubutsukan (Syonan Museum), July 1943. Photo donated by Mdm Michiyo Haneda. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.The library played a pivotal role during the Occupation years in protecting the collections of the institutional and private libraries of the colonial secretariat, survey office, consulates, law firms and other key entities. The materials were deposited by the Custodian of Enemy Property and stowed away in the library and in Wesley Methodist Church located behind – and returned to their rightful owners after the war. During the Occupation, William Birtwistle of the Fisheries Department and a team of library staff also salvaged the manuscript records of the East India Company which were found drenched and strewn across the floors of the Fullerton Building. As for the lending library, some of its books were sent to Allied prisoners-of-war camps and the rest transferred to the old St Andrew’s School. The space was then converted into a public library for Japanese books.

A tangible link to this tumultuous period is the library’s collection of newspapers published during the Japanese Occupation, The Syonan Times (later The Syonan Shimbun) and the Chinese version, Zhaonan Ribao (昭南日报).11 Museum and library staff, and the renowned botanist, Edred John Henry Corner, deserve much of the credit for saving these papers. In his autobiography, Corner wrote: “In a moment of inspiration in February 1942, I had seen that the only written record, however propagandist and fallacious it might be of the Occupation, would be the newspapers.”12 At great personal risk, he surreptitiously kept them in the archives room and managed to collect about half of the issues. When the collection grew too large to conceal, he hid them in the specimen cabinets of the Botanic Gardens. Today, these newspapers serve as a vital record of this dark period in Singapore’s history.

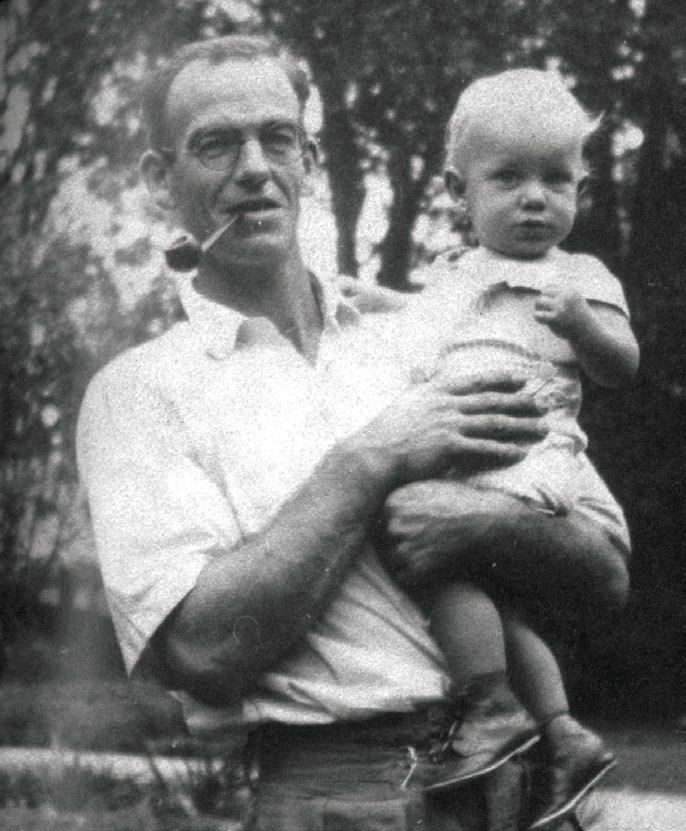

Edred John Henry Corner with his son, John, mid-1941. Corner was the Assistant Director of the Botanic Gardens (1929–45) and deserves much of the credit for saving newspapers published during the Japanese Occupation of Singapore. All rights reserved, Corner, J. K. (2013). My Father in His Suitcase: In Search of E. J. H. Corner the Relentless Botanist. Singapore: Landmark Books.

Edred John Henry Corner with his son, John, mid-1941. Corner was the Assistant Director of the Botanic Gardens (1929–45) and deserves much of the credit for saving newspapers published during the Japanese Occupation of Singapore. All rights reserved, Corner, J. K. (2013). My Father in His Suitcase: In Search of E. J. H. Corner the Relentless Botanist. Singapore: Landmark Books.Separation of the Library and Museum

After the Japanese left Singapore, a slew of plans were proposed for the modernisation of the library. Principal among these was the establishment of a free public library. To this end, the businessman and philanthropist Lee Kong Chian offered $375,000 towards the formation of a free public library in 1953 on condition that the library also agreed to collect vernacular books. This paved the way or the establishment of the National Library and the separation from the museum.

The idea of a separation was not new. As early as 1894, librarian and curator George Darby Haviland had made the observation that “that the narrower interests of Singapore residents, centred in the Lending Library, are in great part antagonistic to the broader Rafflesian interests of a Public Museum and Library for the benefit of all who make use of Singapore as a commercial centre”.13 In 1920, the matter was raised again but no decision was made in view of the recent building extensions. Instead, a Biological Library, attached to the museum, was formed with a selection of literature taken from the Raffles Library. In 1923, the botany books from the Biological Library (also called the Museum Reference Library) were given away to the library of the Botanic Gardens.

By 1949, the library and museum had three specialist libraries, the “Q” Room, the Zoological Library and the Anthropological Library, all of which came under the museum to support research on Malaya. A catalogue of the scholarly journals was published in 1950, titled A Working List of the Scientific Periodical Publications Retained in the Raffles Museum and Library.

It was only in 1955 that the formal administrative split of the library and museum took place. The special collections on zoology, anthropology and archaeology went to the Raffles Museum, while the “Q” Collection came under the Raffles Library. However, it would take another five years before the library had a building of its own, with the “Q” Collection forming the nucleus of the Southeast Asia Room at the future National Library.

These sweeping changes, which also saw the Printers and Publishers Ordinance and the States Archives coming under the administration of the library, were officially instituted through the enactment of the Raffles National Library Ordinance in 1958. On 12 November 1960, the library finally moved out of the museum building into its new premises, the red-bricked National Library building on Stamford Road.

Today, the dispersed holdings of the Raffles Library and Museum exist in the collections of the National Library at Victoria Street and the Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum at the National University of Singapore. Parts of the collections can also be found in the Library of Botany and Horticulture of the Botanic Gardens and the staff collection of the National Heritage Board museums.

“From the Stacks: Highlights of the National Library” is an ongoing exhibition that features several items from the Rare Materials Collection mentioned in this article: the first reports of the Singapore Library (1844–52); books inherited from the Singapore Library; the first edition of the Straits Times Almanack and Directory (1846); the first lithographed edition of Hikayat Abdullah (1849); and original copies of The Syonan Shimbun and Zhanonan Ribao ((昭南日报) newspapers.

Visitors will also get to see letters penned by Stamford Raffles and his wife Sophia; an intricate “Loyalty Address” presented by local Chinese merchants to Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, in homage of his visit to Singapore in December 1869; as well as some of the the earliest materials published in or about Singapore.

In conjunction with the exhibition, the National Library has planned guided tours, talks and workshops, including a birdwatching tour, a conservation talk by archivists and a heritage cooking demonstration.

The exhibition is held at the National Library Gallery, Level 10, National Library Building, until 28 August 2016. Admission is free. For more information on the exhibition and its programmes, check: www.nlb.gov.sg/exhibitions

Gracie Lee is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. She works with the rare materials collections, and her research areas include Singapore’s publishing history and the Japanese Occupation.

Gracie Lee is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. She works with the rare materials collections, and her research areas include Singapore’s publishing history and the Japanese Occupation.

REFERENCES

Book show for Malaya. (1947, July 27). The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Buckley, C.B. (1984). An anecdotal history of old times in Singapore (pp. 122–139). Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 BUC)

Corner, E.J.H. (1981). The Marquis: A tale of Syonan-to. Singapore: Heinemann Asia. (Call no.: RSING 959.57023 COR)

Daniel, P. (1941). A descriptive catalogue of the books relating to Malaysia in the Raffles Museum & Library, Singapore. Singapore: [Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society]. Call no.: RCLOS 016.9595 DAN)

Dennys, N.B. (1880). A contribution to Malayan bibliography. Singapore: Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. Retrieved from BookSG.

Hanitsch, R. (1991). Raffles Library and Museum, Singapore. In W. Makepeace, G.E. Brooke & R.St. J. Braddell. (Eds.), One hundred years of Singapore (Vol. 1, pp. 519–560). Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 ONE)

Journal in the federal capital. (1932, April 16). The Straits Times, p. 16. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Khoo, B.L. (1972, September 8). A jealous guard on Singapore’s earliest books. New Nation, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Liu, G. (1987). One hundred years of the National Museum: Singapore 1887–1987. Singapore: The Museum. (Call no.: RSING 708.95957 LIU)

Lum, M. (1986, October 4). Glimpses of life in pre-war days. The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Malaya’s first printed book. (1948, October 3). The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Quah, R. (1973). The Southeast Asia Collection of the National Library, Singapore – an appraisal. Singapore Libraries, 3, 32–37.

Quaint delights and surprises in books of Malaya’s past. (1936, January 12). The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Raffles, T.S. (1819). Minute by Sir T.S. Raffles on the establishment of a Malay College at Singapore. [S.l.: s.n.]. Retrieved from BookSG.

Raffles, T.S. (1823). Formation of the Singapore Institution, A. D. 1823. Malacca: Printed at the Mission Press. Retrieved from BookSG.

Raffles Library. (1877). General catalogue of bound volumes in the Raffles Library, Sept. 1st, 1877. Singapore: The Library. Retrieved from BookSG.

Raffles Library. (1881). Catalogue of the Logan Library. Singapore: Printed by Straits Times Press. (Call no.: RRARE 015.5957 RAF; Microfilm nos.: NL3998; NL2805)

Raffles Library. (1897). Catalogue of the Rost Collection in the Raffles Library Singapore. Singapore: Printed at the American Mission Press. Retrieved from BookSG.

Raffles Library. (1957–1958). Annual report. Singapore: The Library. (Call no.: RRARE 027.55957 RLSAR)

Raffles Museum. (1950). A working list of the scientific periodical publications retained in the Raffles Museum and Library, Singapore. Singapore: Govt. Print. Off. (Call no.: RCLOS 015.5951 RAF)

Raffles Museum and Library. (1876–1955). Annual report. Singapore: The Museum. (Call no.: RRARE 027.55957 RAF; Microfilm nos.: NL3874, NL5723, NL25786)

Seet, K. K. (1983). A place for the people. Singapore: Times Books International. (Call no.: RSING 027.55957 SEE)

Singapore Institution Free School. (1834–1862). Report (Singapore Institution Free School), 1834–62. Singapore: Printed at the Mission Press. Retrieved from BookSG.

Singapore Library. (1844–1860). Report. Singapore: Singapore Library. Retrieved from BooKSG.

Singapore Library. (1860). Catalogue of books in the Singapore Library, with regulations and by-laws, September 1860. Singapore: Printed at the Mission Press. Retrieved from BooKSG.

Tan, K. (2015). Of whales and dinosaurs: The story of Singapore’s Natural History Museum. Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING 508.0745957 TAN)

Van der Hoop, A.N.J. (1957). The Raffles Museum Singapore. [S.l., s.n.]. (Call no.: RDLKL 069.2095957 VAN)

NOTES

-

Reith, G.M. (1892). Handbook to Singapore (pp. 36–37). Singapore: Singapore and Straits Print. Office. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

Raffles, T.S. (1819). Minute by Sir T.S. Raffles on the establishment of a Malay College at Singapore (pp. 17, 24). [S.l.: s.n.]. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

Singapore Library. (1850). The sixth report of the Singapore Library (p. 7). Singapore: Printed at the Singapore Free Press Office. Retrieved from BooKSG. ↩

-

Singapore Library. (1849). The fifth report of the Singapore Library (pp. 10, 20). Singapore: Singapore Free Press Office. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

Hanitsch, R. (1991). Raffles Library and Museum, Singapore. In W. Makepeace, G.E. Brooke & R.St. J. Braddell. (Eds.), One hundred years of Singapore (Vol. 1, p. 546). Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 ONE) ↩

-

Raffles Museum and Library. (1880). Report on the Raffles Library and Museum for 1879 (p. 1). Singapore: The Museum. (Call no.: RRARE 027.55957 RAF; Microfilm no.: NL3874) ↩

-

This title is currently on display at the library’s “From the Stacks” exhibition. ↩

-

This title is currently on display at the library’s “From the Stacks” exhibition. ↩

-

Daniel, P. (1941). A descriptive catalogue of the books relating to Malaysia in the Raffles Museum & Library (p. i). Singapore. Singapore: [Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society]. Call no.: RCLOS 016.9595 DAN) ↩

-

The author wishes to thank Dr Peter Borschberg for his assessment of the Mills Collection. ↩

-

A selection of newspapers from the Occupation period are on display at the “From the Stacks” exhibition. ↩

-

Corner, E.J.H. (1981). The Marquis: A tale of Syonan-to (p. 151). Singapore: Heinemann Asia. (Call no.: RSING 959.57023 COR) ↩

-

Raffles Library. (1894). Annual report on the Raffles Library and Museum, for the year ending 31st December 1893 (p. 1). [S.l.: s.n.]. (Call no.: RRARE 027.55957 RAF; Microfilm no..: NL3874) ↩