Angels in White: Early Nursing in Singapore

In the 1820s, some “nurses” in Singapore were actually chained convicts. Pattarin Kusolpalin chronicles the history of nursing from 1819 until Independence.

Nuns from the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus at Victoria Street taking care of babies abandoned at the convent, early 1900s. Many of these French nuns took up nursing duties at the General Hospital on 1 August 1885 due to the shortage of trained professionals. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

Nuns from the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus at Victoria Street taking care of babies abandoned at the convent, early 1900s. Many of these French nuns took up nursing duties at the General Hospital on 1 August 1885 due to the shortage of trained professionals. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.Singapore celebrates Nurses’ Day on 1 August each year to mark the beginnings of nursing here – when French nuns from the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus first began nursing duties in the General Hospital at Sepoy Lines1 in 1885. Today, there are more than 37,000 nurses and midwives in Singapore, making up more than half of its professional healthcare workforce.

Since 1 August 2000, exemplary nurses have received the President’s Award for Nurses – the highest accolade given to nurses in recognition of their tireless contributions to society. Nursing in Singapore has certainly come a long way from the early days when “nurses” were chained convicts.

The Beginnings of Nursing: 1800s

When Stamford Raffles arrived in Singapore in January 1819, a skeletal medical team accompanied his troops. This all-male detachment consisted of military doctors, apothecaries (equivalent to modern-day pharmacists), orderlies as well as dressers (who specialised in wound dressing and bandaging).

In the same year, a wooden shed was erected near the junction of Bras Basah Road and Stamford Road to treat as well as house sick soldiers. This rudimentary shed, which was rebuilt in 1821, served as a general hospital staffed by army surgeons and is regarded today as the predecessor of the Singapore General Hospital.2

Unfortunately, access to early healthcare back then was mostly a privilege that only colonial administrators and the military enjoyed; the indigenous people and immigrants were largely left to fend for themselves.

As there were no nurses at the time, basic “nursing” at the hospital was carried out by unwilling chained convicts.3 As the convicts moved around the wards, the awful clank and clatter of their metal chains dragging on the floor and banging against furniture did not provide much comfort to the patients.

The establishment of a British trading outpost by Raffles in Singapore soon led to its development as a port. As Singapore’s reputation grew and more people arrived on the island to trade and to seek better prospects, there grew an urgent need to provide medical facilities for residents. The available healthcare was very basic and the situation was made worse by the lack of qualified medical personnel. There were no local physicians and those who served in Singapore were mainly military doctors posted from either Britain or India.

Between the 1820s and 80s, the General Hospital moved locations several times and assumed different names while private hospitals like the Chinese Pauper’s Hospital (which later became Tan Tock Seng Hospital) was constructed to meet the growing demand for healthcare. These “hospitals” offered very basic medical facilities for the sick and were nowhere near the modern definition of hospitals as we know them today.

The main challenge of these hospitals was to recruit qualified staff – a problem the profession would continue to face in the decades to come. At the makeshift General Hospital in the Bras Basah and Stamford Road area, the fully occupied apothecaries, orderlies and dressers had to cover “nursing” duties in addition to their own work. Apart from forced convict labour, servants and even fellow patients were roped in to provide care for the sick and infirm.

As the female population increased and hospitals began admitting women, requests for female carers arose. Before the 1850s, women did not go to hospitals and received their treatments at home. It was unheard of to give birth in a hospital as most women preferred to undergo the process of childbirth in the privacy of their own homes. One can imagine the difficulties female patients and their male healthcare assistants faced in those days – this was the time when any form of physical contact between members of the opposite sex was frowned upon.

In 1856, the post of a female attendant was included in the plan for the new General Hospital and Lunatic Asylum in Kandang Kerbau district, but it was not approved. In 1861, when the hospital was completed, the Residency Assistant Surgeon, Dr James Cowpar, suggested that “one of the convicted women should be attached to the Ward as a nurse”.4 Although records show that the General Hospital at Kandang Kerbau was treating women for gynaecological problems and providing childbirth services by 1866, there was still no female attendant working there. Instead, male convicts were made to serve the female wards at this hospital as well as its adjacent Lunatic Asylum.

In January 1867, the colonial administration finally approved the request for a female attendant to work in both institutions. One can imagine the heavy workload of Singapore’s very first female “nurse”, having to run between the two premises, and earning a measly monthly wage of 22 rupees. Nevertheless, this was a significant event in Singapore’s nursing history, marking the first time a female employee was employed in the Medical Department.

In 1873, an outbreak of cholera occurred at the Lunatic Asylum at Kandang Kerbau, and patients at the General Hospital next door were evacuated to temporary premises at Sepoy Lines, located in the area around the junction of Outram Road and New Bridge Road. On 1 August 1882, the new General Hospital replaced the old buildings at Sepoy Lines. Although the inclusion of British trained professional nurses had been suggested as part of its staffing, the recommendation was not implemented as the hospital administrators felt it would be difficult to recruit such nurses to work in Singapore. Until then, “nursing” tasks were performed largely by hospital servants, while the more serious cases were supervised by the general staff, with the assistance of more able patients.

The 1883 Medical Report submitted by Dr Max F. Simon, Surgeon in Charge of the General Hospital at Sepoy Lines, to Dr T. Irvine Rowell, its Principal Civil Medical Officer, highlighted that the “two great drawbacks to satisfactory treatment of patients are the inferior quality of the native servants and the absence of proper nursing”. The report also recommended that the General Hospital employ “a Matron and two Nurses”.5 The government agreed that the General Hospital was in dire need of trained nurses and better nursing facilities. Faced with difficulties in recruiting nurses from Madras and England, the government had to find an alternative solution. The proposed plan was to train the French nuns from the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus – viewed as the only educated and qualified European women in Singapore then – who were prepared to undertake this selfless work.

The proposal was immediately met with objections by some segments of the public. Led by European residents, a petition was submitted to the government. Nursing at the time was considered as charitable work and perceived to be very much part of one’s religious beliefs. As the nuns were Roman Catholics, there were fears that their loyalties would lie with the Catholic Church instead of the government and that medical services in the country would eventually be taken over by the Catholic bishop. In addition, there were concerns among some conservatives about placing the nuns in close physical contact with male patients, or people of different religious faiths, even when it concerned saving lives.

Despite vehement protests, the government went ahead and appealed to the convent. Thankfully, common sense prevailed and the nuns began their nursing duties at the General Hospital on 1 August 1885.6 This date officially marks the beginnings of nursing in Singapore.

In 1896, the Colonial Nursing Association was formed in England to see to the nursing needs of the British colonies. In August the same year, it was reported that the Shanghai Municipality had employed trained nurses from England. The hospital in Kuala Lumpur also had British-trained nurses since December 1895 in its workforce. This news and similar reports piqued public interest, including that of Lady Mitchell, wife of Governor Charles Bullen Hugh Mitchell, who was most concerned over the care of patients in government institutions.

The following years saw many public letters, newspaper editorials and meetings that emphasised the need for professionally trained nurses. In 1899, The Straits Times accepted subscriptions and donations to fund the recruitment of nurses from England.7 The public donated generously. By May 1900, the French nuns had withdrawn from their nursing duties at the General Hospital, and in the same month, four qualified nurses arrived from England and took over the care of the patients.

Later Developments: 1900–40

The minimum entry requirement for nursing school in the early 1900s was the completion of the Junior Cambridge Examination. The very fact that trained nurses had to be recruited from overseas highlighted the dismal state of education among local women in Singapore. Most women in those days were confined to traditional domestic roles – as daughters, wives and mothers – and generally did not receive much education.

A male attendant in a ward of the old Tan Tock Seng Hospital. As the first professionally trained nurses did not arrive in Singapore till 1900, male attendants took care of patients. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A male attendant in a ward of the old Tan Tock Seng Hospital. As the first professionally trained nurses did not arrive in Singapore till 1900, male attendants took care of patients. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.However, by the end of 1903, all the four qualified nurses from England had left their posts for various reasons: a transfer out of Singapore, marriage, ill health or completion of their three-year contracts. Although they were replaced by other expatriates, the pool of trained nurses remained largely stagnant. Subsequent arrivals succumbed to illnesses such as tuberculosis and malaria as they were unused to working in a tropical country. In 1911, for instance, seven out of 10 Sisters and six out of 13 Nurse Probationers were admitted to hospital.

Maternal and child health was not a major concern of the colonial government in the early years of the 19th century as the migrant population was mainly male and the local Malay community had their own birth practices. It was not until 1888 that the first eight-bed maternity hospital was set up at the junction of Victoria Street and Stamford Canal. The hiring of a qualified midwife named Mrs. R. Woldstein that year is the first record of a trained midwife in Singapore.

In 1908, the infant mortality rate was 347.8 per one thousand live births, with almost 60 percent of deaths occurring during the first three months of birth. To give a sense of how far we have come, Singapore’s infant mortality rate in 2015 was 1.7 per one thousand live births.

With rising concerns over the high infant mortality rate, Miss J. E. Blundell from England was appointed as Municipal Nurse8 early life conditions of infants. The findings confirmed that poor infant feeding was the main contributor to infant mortality. Miss Blundell was subsequently asked to instruct local mothers on the proper care of their infants and young children. Her findings led to the start of a regular midwifery course for local women in 1910, with proper instruction and licensing of midwives. That year marked the beginning of the Maternal and Child Health Service in Singapore.

The nursing profession, as most people will readily admit, is one of the toughest in the world; it is a calling that requires dedication and a certain steadfastness of spirit. While nurses today face many challenges on a daily basis, it was much worse back in the 1920s. Nurses were expected to perform six weeks of continuous morning and afternoon shifts, followed by two weeks of night duty. Rest days were scant: student nurses were given one off day per month, while staff nurses had two days. Nurses were also required to live in hospital quarters and have their meals there. Each staff nurse was entitled to her own bedroom, whereas student nurses had to share a room with two other fellow students. Perhaps the most draconian ruling was that nurses working in government hospitals in the 1920s were not allowed to get married. We do not know how long this rule was enforced, but it is little wonder that the profession had difficulties attracting women.

EARLY MIDWIFERY AND THE BIDAN

Prior to the arrival of the British, women in Singapore had their own birth rituals and customs. As the population was mainly Malay, home births were handled by the bidan, usually a well-respected female member of the community. These traditional Malay midwives acquired their skills and knowledge from older, more experienced bidan, and in turn, imparted their knowledge to other women. It was expected of a practising bidan to have gone through pregnancy and childbirth herself.

This 1950 photo shows a midwife weighing a newborn baby at home. As hospital beds in maternity hospitals were in short supply in the 1950s, women were discharged 24 hours after their babies were born. Midwives would visit these new mothers at their homes to provide postnatal care. School of Nursing Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

This 1950 photo shows a midwife weighing a newborn baby at home. As hospital beds in maternity hospitals were in short supply in the 1950s, women were discharged 24 hours after their babies were born. Midwives would visit these new mothers at their homes to provide postnatal care. School of Nursing Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

In Singapore, midwifery training started earlier and advanced more rapidly than general nursing. Commencing in 1896, midwifery training was reserved only for married women until 1901, when three unmarried midwives passed the examination. In the early days, all midwives and probationers were of European ancestry; it was not until 1910 that the first course for Asian midwives kicked off. Malay bidan, however, preferred to stick to their own training programme that followed time-honoured Malay customs and traditions.

One of the earliest records of a healthcare outreach programme in Singapore was in 1911 when infant welfare nurses made house visits to inspect the living conditions of infants and to advise young mothers. The results were significant: Singapore’s infant mortality rate fell to 267 per one thousand live births in 1912. In 1915, the Midwives Ordinance was passed to recognise certified midwives and require their compulsory registration in the Straits Settlements by the Central Midwives Board.

When World War I broke out in July 1914, many British nurses volunteered for service in the Armed Forces in England, including Miss M. J. McNair, then the Head Nurse9 of the General Hospital at Sepoy Lines. While all this was perfectly laudable of course, it put a severe strain on the existing nursing staff in Singapore, and it became extremely difficult to find replacements for nurses who left the country.

The shortage of qualified nurses had been a perennial problem since the concept of healthcare first emerged in Singapore. Although there had been attempts at providing some form of training for local nurses in hospitals since the 1880s, it was rather haphazard; the training was mostly unstructured and whatever nurses learnt was very much on-the-job. It was only in 1916, when St Andrew’s Mission Hospital started a General Nurse Training course for local girls – adopting the established British curriculum for training and education – did coaching in Singapore take on a more formal and organised approach.

The student nurses, who were recruited on an apprenticeship model, were sent directly to the hospital wards to work and receive on-the-job training. Learning was through observation, following instructions and assisting the staff nurses, sisters and doctors. Expatriate nurses assumed the training and supervisory roles, with the local nurses working under them.

Despite the concerted efforts, the nursing staff in 1921 consisted of just 16 trained nurses and 36 probationers in the government service. In the same year, there were only one staff nurse and three probationers at the St Andrew’s Mission Hospital. Attrition was mainly due to resignations from nurses who sought better opportunities elsewhere.

In 1922, the St Andrew’s Mission Hospital revised its nurse training curriculum: student nurses were put on a three-month probationary period, followed by a three-year course in General Nursing and Midwifery with examinations taken at the end of each year.

In 1924, the General Hospital at Sepoy Lines commenced its four-year General Nursing and Midwifery training programme. After six months in the programme, it was compulsory for student nurses to attend weekly lectures conducted by senior doctors and matrons as well as sit for the annual examinations. If the student nurses passed the final examination at the end of the third year, they would proceed to do a one-year midwifery training course at either the maternity block (opened in 1908) of the General Hospital at Sepoy Lines or Kandang Kerbau maternity hospital (which was converted into a specialist maternity hospital in 1924). Upon completion of the four-year programme, successful candidates received certification and were promoted to staff nurses.

To bring festive cheer to the patients, wards at the General Hospital were decorated with Christmas trimmings, circa 1930s. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

To bring festive cheer to the patients, wards at the General Hospital were decorated with Christmas trimmings, circa 1930s. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.In 1926, Singapore’s first public health nurse, Miss Ida M. M. Simmons (see text box below) from Scotland, was employed to provide infant and maternal health services to mothers and infants in rural areas. As a result of her recommendations, a mobile dispensary was introduced the following year. The medical team consisted of a doctor, dresser and nurse who made daily trips to rural areas. In addition, nurses were involved in various outreach activities to educate school children and the general public on hygiene and basic health. Local nurses also gained recognition. Mrs Maude Ethel Perera joined the Health Branch as a staff nurse in 1929. This was the first time an Asian was deemed to be on par with expatriate nurses and qualified to lead.

World War II to Independence: 1940s–65

The outbreak of World War II and the fall of Singapore on 15 February 1942 brought a halt to the development of nursing, as with most other things, in Singapore. Nurses were allowed to leave the hospitals. Those who opted to remain were transferred to the Mental Hospital (the predecessor of Woodbridge Hospital, better known as the Institute of Mental Health today) at Yio Chu Kang, together with the patients. During the Japanese Occupation, all nurses were required to attend Japanese-language lessons held in the hospitals on top of their regular lectures. Many nurses continued to serve valiantly throughout the difficult war period. With the departure of the Japanese forces after the war and the return of the British, the General Nurse Training course was reintroduced in 1946.

World War II helped to change public perception of local nurses. In January 1947, the government promoted locally trained nurses to the rank of Sister, creating opportunities for them to rise to supervisory and administrative posts. The nurses, many of whom made positive contributions during the Occupation years and survived the war, were more confident of their abilities now and lobbied for their certification to be recognised in the UK and the Commonwealth as well as internationally. In February 1949, the Nursing Registration Ordinance was passed, requiring all nurses to be registered or admitted by examination.

While the post-war demands for nurses soared, the recruitment of student nurses was still abysmal mainly due to the lack of local women with the required level of education. To ease the shortage, nurse training for males was introduced in 1948. Existing male students from the Hospital Assistants training programme were transferred to this new course. In addition, the Catholic religious community came forward once again: nuns from the Franciscan Missionaries of the Divine Motherhood – many of whom were trained nurses and midwives – volunteered their services at the Tan Tock Seng Hospital between 1949 and 1962.

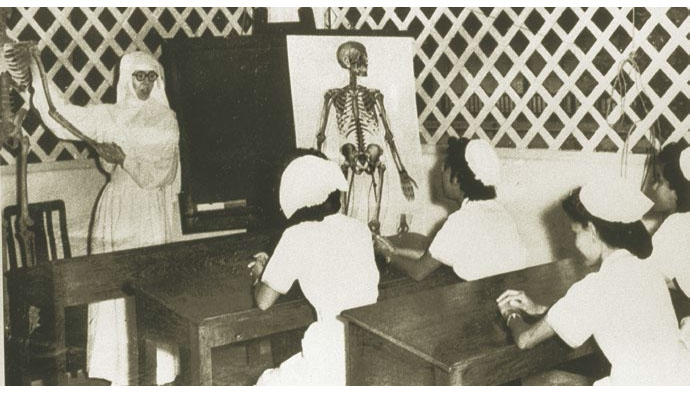

A nun from the Franciscan Missionaries of the Divine Motherhood conducting an anatomy class for nurses at the Mandalay Road Hospital in 1950. School of Nursing Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A nun from the Franciscan Missionaries of the Divine Motherhood conducting an anatomy class for nurses at the Mandalay Road Hospital in 1950. School of Nursing Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.The early 1950s saw recruitment efforts being ramped up, with better prospects, training and promotion opportunities for nurses. Nursing was also portrayed in the media as a respectable career. The marketing efforts paid off and the number of student nurses grew considerably. But demand always seemed to outstrip supply and the nursing shortage persisted.

(Left) Children receiving medical treatment from a mobile dispensary in 1951. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

(Left) Children receiving medical treatment from a mobile dispensary in 1951. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.On 1 March 1951, the Assistant Nurse Training course was started at Tan Tock Seng Hospital to provide a bigger pool of trained nursing professionals. The course offered a path towards a career in nursing for girls without the required level of education and admitted students with Standard VII10 qualifications.

The new School of Nursing, managed by the Singapore General Hospital, opened at Sepoy Lines in 1956. With an increase in the number of nurses, it became necessary to both document and implement proper nursing procedures. Towards this end, a Nursing Education Committee was set up in 1958 to oversee and regulate the various nursing training programmes. In 1959, the first Handbook on Nursing Procedures was published.

This period saw great strides being made to raise the status of nursing in Singapore. The Singapore Trained Nurses’ Association (today known as the Singapore Nurses Association) was founded in 1957 to promote the advancement of nursing as a profession, and in 1959 and 1961 respectively, the association was granted associate and full membership by the International Council of Nurses. Finally, Singapore nurses had attained the international recognition they deserved.

Nurses’ Week was celebrated for the first time in Singapore in May 1965. Held annually for nearly two decades, the programmes and activities organised during the week-long affair included graduation ceremonies for nurses and midwives, concerts, exhibitions, blood donation drives and charity fundraising projects. Nurses’ Week was changed to Nurses Day in 1985.

Unlike most other countries, which celebrate Nurses Day on 12 May, the birthday of Florence Nightingale, Singapore celebrates Nurses Day on 1 August as it commemorates the exact date 131 years earlier when a group of French nuns in Singapore answered the call to become nurses – despite their lack of training and experience, and in the face of much public objection and protests. The nursing profession today has grown exponentially since 1965, but that subject is material for another article of its own.

Ida M. M. Simmons was Singapore’s first public health nurse. Fresh off the boat from Scotland, she joined the Straits Settlements Medical Department in December 1926 and was tasked with introducing infant and maternal health services in rural Singapore, an area then covering almost half the island.

In 1927, Singapore’s first public health nurse, Ida M. M. Simmons from Scotland, was employed to provide infant and maternal health services to mothers and infants in rural areas. All rights reserved, Ministry of Health. (1997). More than a Calling: Nursing in Singapore Since 1885 Singapore: Ministry of Health.

In 1927, Singapore’s first public health nurse, Ida M. M. Simmons from Scotland, was employed to provide infant and maternal health services to mothers and infants in rural areas. All rights reserved, Ministry of Health. (1997). More than a Calling: Nursing in Singapore Since 1885 Singapore: Ministry of Health.

In 1927, some 263 out of every 1,000 babies in Singapore died in their first year, while among rural Malays the number was almost 300 per 1,000 births. Simmons learned Malay and set out to visit every kampong (village) to uncover the extent of the problem. The health department launched a mobile dispensary to make her work easier. The vehicle travelled the rural byways and parked nearby while Simmons and her team made house calls, sending those needing medical attention to the dispensary or summoning the accompanying doctor to the house.

Simmons and her staff earned the patients’ trust through their home visits and by 1930, formal welfare centres had been established. These centres focused on education and prevention, and provided regular check-ups, free milk, referrals to hospitals, lectures and counselling. By the time Simmons retired in 1948, there were 15 full-time centres.

In 1934, Simmons was promoted to Public Health Matron for rural Singapore. During the Japanese Occupation of Singapore (1942–45), Simmons was interned at Sime Road Camp. After the war, she began rebuilding infant health services, which had been neglected under the Japanese. Infant mortality had worsened but the damage was soon reversed and services were extended to the small outlying islands of Singapore.

Simmons retired to England in 1948, after having overseen a drop in the infant mortality rate from 263 deaths per 1,000 babies in 1927 to an exceptional record of 57 deaths per 1,000 babies that year. This was a feat especially when viewed against the backdrop of a rising birth rate. She later moved to Scotland, where she died in 1958.

Extracted from Singapore Infopedia: National Library Board. (2013, March 25). Ida Simmons written by Sutherland, Duncan. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website.

Pattarin Kusolpalin is a former Librarian at the National Library, Singapore. Her responsibilities included collection management, content development, and the provision of reference and information services.

Pattarin Kusolpalin is a former Librarian at the National Library, Singapore. Her responsibilities included collection management, content development, and the provision of reference and information services.

REFERENCES

Department of Information Services, “Citations for the Presentation of Awards & Insignias by H.E. the Governor at Government House on Saturday, July 26, 1958 at 11 a.m.,” press release, 26 July 1958. (From National Archives of Singapore document no. PressR19580726a)

Edwards, N., & Keys, P. (1988). Singapore: A guide to buildings, streets & places (pp. 340–341). Singapore: Times Books International. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 EDW)

Fildes, V., Marks, L., & Marland, H. (Eds.). (1992). Women and children first: International maternal and infant welfare, 1870–1945. London: Routledge. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Government of Singapore. (2016, May 26). Latest data. Retrieved from Singapore Department of Statistics website.

Gwee, M.B., & Ang, R. (1991). Trends in nursing education in Singapore. The Professional Nurse: A Quarterly Publication of the Singapore Trained Nurses’ Association, 18 (3), p. 17.

Lee, C.E., & Satku, K. (Eds.). (2016). Singapore’s health care system: What 50 years have achieved (p. 169). Singapore: World Scientific. (Call no.: RSING 362.1095957 SIN)

Lee, Y.K. (1985 February). The origins of nursing in Singapore. Singapore Medical Journal, 26 (1), 53–60. Retrieved from Singapore Medical Association website.

Lee, Y.K. (2005, November). Nursing and the beginnings of specialised nursing in early Singapore. Singapore Medical Journal, 46 (11), 600–609. Retrieved from Singapore Medical Association website.

Legislative Council. (1884, December 6). Straits Times Weekly, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Lim, M. (1966). The maternal and child health services in Singapore. Journal of the Singapore Paediatric Society, 8 (1), 29–41.

Makepeace, W., Brooke, G.E., & Braddell, R.S.J. (Eds.). (1991). One hundred years of Singapore. Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 ONE)

Medical report for 1883. (1884, April 12). Straits Times Weekly, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Midwives and nurses in jog to raise $40,000. (1985, May 1). The Straits Times, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Mudeliar, V., Nair, C.R.S., & Norris, R.P. (Eds). (1979). Development of hospital care and nursing in Singapore. Singapore: Ministry of Health. (Call no.: RSING 610.73095957 MUD)

Municipal commission. (1910, August 6). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Municipal nurses. (1896, August 19). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Municipal Singapore. (1909, November 17). The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

National Library Board. (2016). Singapore General Hospital written by Naidu, Ratnala Thulaja. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website.

Page 7 Advertisements Column 1. (1887, August 12). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Singapore. Ministry of Health. (1997). More than a calling: Nursing in Singapore since 1885. Singapore: Ministry of Health. (Call no.: RSING 610.73069 MOR)

Singapore Nurses Association. (2015). Our history. Retrieved from Singapore Nurses Association website.

Singapore Nursing Board. (2016). Retrieved from Singapore Nursing Board website.

Tan, K.H., & Chern, S. M. (2002). Progress in obstetrics from 19th to 21st centuries: Perspectives from KK Hospital, Singapore – the former world’s largest maternity hospital. The Internet Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 2 (2). Retrieved from Internet Scientific Publications website.

Tan, K.H., & Tay, E.H. (Eds.). (2003). The history of obstetrics and gynaecology in Singapore. Singapore: Obstetrical & Gynaecological Society of Singapore: National Heritage Board. (Call no.: RSING q618.095957 HIS)

The local nurse. (1951, April 4). The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Tong, Y.T., & Narayanan, S. (2015). Caring for our people: 50 years of healthcare in Singapore. Singapore: MOH Holdings Pte Ltd for the Ministry of Health. (Call no.: RSING 362.1095957 TON)

Yeoh, B.S.A., Phua, K.H., & Fu, K. (2008). From colony to global city: Public health strategies and the control of disease in Singapore. In M.J. Lewis & K.L. Macpherson (Eds.), Public health in Asia and the Pacific: Historical and comparative perspectives. Abingdon, Oxon; New York: Routledge. (Call no.: R 362.1095 PUB)

NOTES

-

Sepoys were Indian soldiers recruited by the European colonial powers, including the British. Sepoy Lines refers to the area around the junction of Outram Road and New Bridge Road where the barracks for the sepoys were once located. The General Hospital moved to this area in 1882. ↩

-

The General Hospital relocated several times and was known by different names until its final move to Sepoy Lines in the Outram area in 1882. New buildings were subsequently added to the existing ones at Sepoy Lines and the new hospital opened in 1929 as the Singapore General Hospital. ↩

-

Singapore was once a penal colony for convicts from India, Hong Kong and Burma. The first shipment of Indian prisoners arrived in Singapore in 1825 via Bencoolen in Sumatra. ↩

-

The “Ward” referred to the planned female ward of Tan Tock Seng Hospital. The term nurse at this point still referred to any female attendant providing care to the sick, and not a professionally trained nurse. ↩

-

Medical report for 1883. (1884, April 12). Straits Times Weekly Issue, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

As the nuns did not have proper training, their duties were limited to cooking, cleaning and following medical instructions. ↩

-

The Strait Times Committee of Subscribers, formed in 1900, was responsible for funding the British nurses’ employment. ↩

-

Miss J. E. Blundell was previously employed in the Native States. Her monthly salary in Singapore was 100 Straits dollars and came with a travelling allowance not exceeding 25 Straits dollars. ↩

-

The Head Nurse was in charge of the nursing staff. The term was later changed to Matron. ↩

-

During that time, Standard IX was the equivalent of today’s GCE ’O’ Levels. Standard VII was equivalent to present-day Secondary 2. ↩