Forgotten Foods & Mealtime Memories

Food writer Sylvia Tan remembers the foods and flavours she grew up with and the less than sanitary practices made for stomachs cast in iron.

Roadside satay stalls opposite the Tay Koh Yat bus depot along Beach Road, 1955. Source: The Straits Times © Singapore Press Holdings Limited. Permission required for reproduction.

Roadside satay stalls opposite the Tay Koh Yat bus depot along Beach Road, 1955. Source: The Straits Times © Singapore Press Holdings Limited. Permission required for reproduction.What could be more off-putting than dipping sticks of charcoal-grilled satay into a communal pot of peanut gravy at a roadside stall literally metres away from belching buses?

Yet I recall that time with sweet nostalgia, quite forgetting the lung-clogging smoke from the buses that ended their journey at the Tay Koh Yat depot along Beach Road, or worse, dipping a half-eaten stick of satay or cube of ketupat (rice cake) into the communal pot shared with goodness knows how many others who’d just done the same.

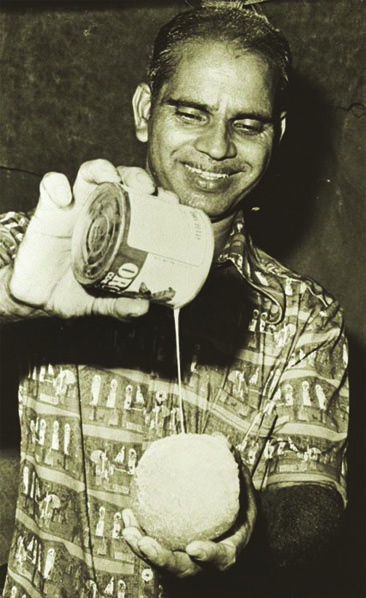

Just as no one bothered if the ice ball man, now long gone, had washed his hands before manhandling and shaping shaven ice into balls for us to lick and suck into. All that concerned us was how generous he was with the multi-coloured syrups he drizzled over these ice balls, finished off with swirls of creamy evaporated milk. What could be more refreshing than icy sweetness crowned by milky creaminess? You could even share the ice ball if you didn’t have enough money, for he’d cut it into half, enough for two.

An Indian ice seller drizzling multi-coloured syrups and swirls of creamy evaporated milk over an ice ball, 1978. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

An Indian ice seller drizzling multi-coloured syrups and swirls of creamy evaporated milk over an ice ball, 1978. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Today, you cannot buy ice balls for love or money, although satay is widely available, albeit no longer served the old-fashioned way. Today, most hawker dishes, no matter their origins, are served in the same cookie-cutter style using disposable crockery and cutlery.

Time was when you didn’t even have to call out your order of satay. Instead, you’d just find a seat and the satay man would grill an assortment of bamboo sticks, threaded with chicken, beef or mutton, which he placed on a communal platter for you to help yourself to. You shared a table with strangers, sitting companionably side by side on low stools. And you paid only for the sticks you took, with the satay man counting the sticks left behind by your plate to tote up your bill. Everyone happily dipped into the same pot of gravy – germs and parasites be damned!

At the old People’s Park in Chinatown in the 1950s – a collection of tumbledown stalls and lean-tos before it was destroyed by fire in 1966 – you could find Chinese food skewered on sticks. This Cantonese street food called lok mei is still available on the streets of Hong Kong but not in sanitary Singapore anymore.

Plates were not necessary at the lok mei pushcart. Instead you picked from the various skewers threaded with virulently coloured morsels of cooked octopus, cuttlefish, chicken wings, pork belly, pig’s ears and other innards. You paid for the sticks you chose and dipped them into tins – again communal – filled with various sauces and condiments such as chilli and hoisin sauce (made from soybeans and garlic) among others, laid out in front of the stall before you went away, happily munching on this takeaway delight.

Home Delivery, Singapore Style

This was a time of mobile food – when hawking was still allowed on the streets – served by pushcart hawkers who’d set up shop at dedicated street corners, completely exposed to the elements. Equally common were itinerant hawkers who made their daily rounds, carting their foods past your doorstep and calling out for customers.

Growing up in post-independent Singapore in the 1960s, I remember spending lunchtime after school perched on my mother’s stone bench outside the gates of our house at the end of a narrow unpaved lorong (road) in Ponggol, waiting for the konlo mee man to pass. Konlo mee is Cantonese dry noodles as we still know it today, dressed with a chilli sauce, garnished with a few slices of char siew (barbequed pork) and perhaps two or three plump wanton, meat dumplings filled with minced pork and scented with sesame oil.

But unlike today’s hawkers, this noodle seller would cry out his wares, in between clacking a set of wooden paddles, which he and other tok-tok men, as they were called, used to announce their arrival in the neighbourhood. The cry of the konlo mee seller was just one of the myriad ways in which hawkers used to jostle for attention in the past.

The ting-ting man who used to peddle his tray of rock candy too is no more: he’d use a small hammer and chisel to break into the hard white candy, the resulting high-pitched clatter of metal against metal giving the name ting-ting. Also long gone is the Indian tikam-tikam man tooting the horn of his small van, a treasure trove of bits and bobs as well as fairground goodies such as candy floss and a shocking pink sweet wafer disc sold from large tins, for which you gambled or played tikam-tikam (Malay for “game of chance”) with the vendor.

Meanwhile the lor ap or braised duck man would cry out “lor ap” in a long nasal cry, carrying his soy-braised ducks, a Teochew speciality, as well as his wooden chopping block, in baskets balanced on a pole across his shoulders. He would chop up the duck as you liked it. You could even ask for just one drumstick, as my grandmother would do, sinking her teeth into its unctuous flesh without waiting for it to be cut up first. Or you could ask for braised innards and duck webs, which modern lor ap sellers of today are unlikely to purvey.

Hawkers today would not dream of pounding the streets in search of customers, lugging their wares on their shoulders as the lor ap man of old did daily. Government restrictions on food handling have put paid to such unsanitary practices. Using just one pail of water to wash dirty crockery throughout the day would not have been tolerated today.

Food on the Go – Literally

I remember these hawkers with fondness for they offered an amazing variety of foods. You could count among this foot army of food sellers the Indian kacang puteh man, who sold a variety of roasted and boiled nuts on a tray balanced precariously on his head, and the putu mayam man who also carried his lacy white rice flour pancakes, eaten with bright orange sugar and shredded coconut, in a basket balanced on his head.

When public housing came into the picture, the nasi lemak boy (they were always boys) would carry packets of banana leaf-wrapped rice with spicy sambal, fried fish or omelette in a basket almost as big as himself along the common corridors of the flats. People hearing the sing-song call of “naaa-si lemaaak” of these boys would scurry out of their flats to buy these savoury coconut-rice parcels for breakfast or a mid-morning snack.

In the days before environmentally destructive styrofoam and plastic takeaway containers appeared on the scene, itinerant hawkers would rely on a range of novel food wrappers, including recycled exercise book paper, fresh banana leaves and dried opeh (palm) leaves to hold their roasted nuts, lacy pancakes, rojak or fried noodles.

This mobile food army also thought of ingenious ways of transporting their food: in baskets, on trays (including a folding trestle stand), which they would balance on their heads, in pushcarts and later, on bicycles, tricycles or small vans, equipped with horns to advertise their arrival – no need for vocal cord-shattering cries or clattering implements anymore.

(Above) A noodle seller along a five-foot-way, 1950. Singapore Chinese Clan Associations Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

(Above) A noodle seller along a five-foot-way, 1950. Singapore Chinese Clan Associations Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.I remember the piercing call of the loh kai yik hawker, crying out “lo-oh kaaai yiiik”, or braised chicken wings in Cantonese, as he traversed the neighbourhoods, sitting comfortably on a tricycle, his pot of stew – coloured pink with tau ju, a fermented soya cheese – gripped between his legs, while his long-suffering assistant pedalled hard to bring him around. He sold a rich stew filled with not only with chicken wings, but also pork belly, innards such as pig’s liver and intestines, ju her (cured cuttlefish), kangkong (water convolvulus) and soya bean puffs. This is an old Cantonese dish that no longer exists, at least not in the food centres.

Loh kai yik, or braised chicken wings, is a Cantonese dish made of chicken wings, pork belly, pig’s liver and intestines, ju her (cured cuttlefish), kangkong (water convolvulus) and soya bean puffs. All rights reserved, Tan, S. (2011). Modern Nonya. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Cuisine.

Loh kai yik, or braised chicken wings, is a Cantonese dish made of chicken wings, pork belly, pig’s liver and intestines, ju her (cured cuttlefish), kangkong (water convolvulus) and soya bean puffs. All rights reserved, Tan, S. (2011). Modern Nonya. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Cuisine.Shout out to him and his assistant would pedal right to your doorstep where the loh kai yik man would swing into action: you specified what you wanted and he’d fish them out from his simmering pot, snip them into smaller pieces with his trusty scissors – an old-fashioned pair with curled handles – and dish them onto enamel plates for you to enjoy – with chilli sauce of course.

Lost Foods

Over the years, plenty of foods have disappeared for various reasons. Take pig’s blood pudding for instance. It used to be cooked in a clear Teochew-style soup, together with minced pork and lavish handfuls of Chinese celery. Pig’s blood, coagulated and cut into squares, was freely sold at markets back in the 1950s. My Teochew father would buy and cook it in a clear soup on Sundays (he belonged to a family where the men took up the ladles on weekends while the womenfolk prepped and cleared up afterwards). Sadly, this soup is no more to be found at home and at hawker centres. Pig’s blood is no longer sold, following the outbreak of Japanese encephalitis at pig farms in Malaysia in 1999.

As for innards, you’d have to specially order it these days from the butchers, doubtless because of dwindling demand from customers more accustomed to less exotic fare. There are few stalls today selling ter huang kiam chye, that tangy Teochew soup made with salted mustard leaves and all manner of pork offal, just as you have to specially order satay perut (beef tripe) from the satay seller if he was coming to your house to cater for a party. Also, I can no longer find that spicy and sour Hainanese mutton innards soup spiked with kaffir lime leaves and chilli called perut kambing (literally goat’s stomach) that used to feature on the menus of tok panjang dinners, named after the long tables used for these Peranakan (Straits Chinese) feasts more than 40 years ago, and whipped up by Hainanese chefs.

This narrowing of food tastes, at least for exotic animal parts – those were the days when nothing went to waste – has also led to the disappearance of two classic dishes: feng, a speciality of the Eurasian community, and tee hee, a festive dish eaten by the Peranakans. Both dishes rely on pig’s lungs, which are no longer sold at the wet markets, and are tedious to prepare. Wee Eng Hwa, daughter of the late President Wee Kim Wee, laments this fact in her cookbook, Cooking for the President.1

In the 1960s, I remember my mother boiling the whole lung in a pot, leaving the windpipe hanging out of the container to drain out its murky juices until the lung, a veritable sponge, could be squeezed clean. The boiled lung was then cut into strips to be fried with tau cheo, a salted soya bean paste, garlic and lots of ginger, together with pork belly and bamboo shoot strips.

A watercolour painting of itinerant food and vegetable vendors from the 1960s by an unknown painter. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

A watercolour painting of itinerant food and vegetable vendors from the 1960s by an unknown painter. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.The lung was similarly the star ingredient in the Eurasian dish called feng, prepped for cooking the same laborious way and then fried together with a mix of spices that included coriander, turmeric and cumin. Aside from lung, you’d also find pig’s liver, ears, belly, heart and other innards, all cut into strips, in the mix. This dish was a speciality at Eurasian households during Christmas, as was tee hee, fried together with the shredded meats and vegetables, for Peranakan families at Chinese New Year.

In the days of pre-refrigeration, the liberal use of vinegar in feng and salty tau cheo in tee hee kept these dishes from turning rancid during the festive period. Both were eaten with white rice and sambal belacan, a condiment of toasted shrimp paste and chilli, but crusty French loaves – often the bread of choice to accompany curries and stews of the past – were a good match too.

Flavours of My Childhood

I am reminded of the stews that I used to eat, made with chicken or corned beef. While chicken curry is firmly established in the Singaporean lexicon of classic dishes, who has recently eaten chicken stew, seasoned with soya sauce, or corned beef thrown into a pot with canned peas, carrots and potatoes? A concoction of Hainanese cooks who worked in European and wealthy Peranakan households, these stews were wonderful marriages of East and West: a Europeanstyle stew of peas, carrots and potatoes, but seasoned with soya sauce. Corned beef stew was whipped up when tinned food – pork luncheon meat, sardines and yes, corned beef – appeared on the shelves.

All manner of recipes were created using these canned standbys, in case an extra guest popped in for dinner, or simply because cooks felt compelled to tweak somewhat bland Western convenience foods for an Asian palate. For those who haven’t tried it, try cooking a corned beef stew if you can, with chunks of corned beef simmering in the pot together with carrots and potatoes. Or try frying canned sardines with chilli, which gets you a fulsome sambal, lifted by the tang of fresh tomatoes.

Both dishes used to make a regular showing, especially on Eurasian tables, as did Breuder cake and love cake. These cakes came courtesy of Sri Lankan burghers, people of Dutch-Sri Lankan ancestry and Eurasians hailing from Java and Malacca.

Breuder cake is a bread-like cake that follows the tradition of the Italian panettone and other yeast cakes, except that in the case of Breuder, toddy or fermented coconut water is used as a raising agent instead of yeast. Food writer Christopher Tan in his book Nerd Baker2 provides a recipe for it except that his version is made using both coconut water and yeast. He further states that Kue Bluder (its Indonesian variation) was traditionally leavened not just with toddy, but also other yeast sources such as tape singkong or fermented steamed cassava.

Breuder cake, of Dutch-Sri Lankan and Eurasian origins, is a bread-like cake that follows the tradition of the Italian panettone and other yeast cakes, except that in the case of Breuder, toddy or fermented coconut water is used as a raising agent. Food writer Christopher Tan’s version uses both coconut water and yeast. All rights reserved, Tan, C. (2015). Nerd Baker: Extraordinary Recipes, Stories & Baking Adventures from a True Oven Geek. Singapore: Epigram Books.

Breuder cake, of Dutch-Sri Lankan and Eurasian origins, is a bread-like cake that follows the tradition of the Italian panettone and other yeast cakes, except that in the case of Breuder, toddy or fermented coconut water is used as a raising agent. Food writer Christopher Tan’s version uses both coconut water and yeast. All rights reserved, Tan, C. (2015). Nerd Baker: Extraordinary Recipes, Stories & Baking Adventures from a True Oven Geek. Singapore: Epigram Books.Like other yeast cakes, Breuder is baked in a ring pan; indeed the name comes from the Dutch word broodtulband, referring to the fluted turban-shaped mould used to make it. Traditionally baked during Christmas, Breuder cake is usually eaten with butter and a slice of Edam cheese, confirming further the Dutch influence.

While I’ve only tasted the modern-day version of Breuder cake, I’ve been lucky enough to have eaten love cake made by a pioneer Singaporean of Sri Lankan origins. This is a rich cake made from wheat semolina, and scented with nutmeg, cinnamon, honey, rose water and lashings of (too much) sugar. A staple at teatime, which is another dying habit with increasing numbers of households of working parents, love cake can also be made with corn or rice semolina.

Such cakes are rarely found these days, unlike Peranakan kueh – delectable combinations of rice flour, coconut and gula melaka (palm sugar) – which seems to have been rediscovered and is popular not only with aspiring home chefs but also commercial establishments offering them for sale.

Not so, however, are the array of pickles and condiments, aside from sambal belacan, that a stay-at-home wife would have turned out in years past. Of course, you can still find commercial varieties of achar or pickles on supermarket shelves, especially the ever-popular Penang achar, a sweet and nutty concoction. But the piquant Peranakan cucumber and stuffed chilli pickle cannot be bought off the shelf, and is only occasionally made in home kitchens by energetic aficionados of the cuisine.

The piquant Peranakan cucumber and stuffed chilli pickle cannot be bought off the shelf, and is only occasionally made in home kitchens by energetic aficionados of the cuisine. All rights reserved, Tan, S. (2011). Modern Nonya. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Cuisine.

The piquant Peranakan cucumber and stuffed chilli pickle cannot be bought off the shelf, and is only occasionally made in home kitchens by energetic aficionados of the cuisine. All rights reserved, Tan, S. (2011). Modern Nonya. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Cuisine.Rarer still is jerok from my father’s time – a mustard leaf pickle fermented with ahm, or rice porridge water, and fresh coconut water. Together with achar, it used to be offered with gin and tonic that the mem and tuan besar – as the British housewife and her husband in colonial households were referred to – would quaff down at sundown.

Neither seen these days is assam sinting, pickled window-pane shells or local oysters that one could forage from the beach at Tanah Merah. People would remove these bivalves from their pretty mother of pearl shells, stuff them into empty brandy bottles together with salt and leave the mixture to cure. Thankfully, cincalok, fermented grago or shrimp fry, can still be bought, but it’s not a patch on the homemade variety. Also no longer found are baby clams, or remis, that one could dig up along the old beach at Telok Paku and pickle them, shells included, in dark soya sauce.

All these cured seafoods were invariably eaten with sliced fresh chillies, shallots and lime juice, although there were variations with some families adding a few drops of sesame oil to the cincalok and others sprinkling roasted rice powder to assam sinting for an aromatic finish.

If the rise of the working woman didn’t kill such domestic activity, land reclamation and coastal pollution certainly put an end to beach foraging; indeed who forages for periwinkles, the curled shellfish, these days? As a child, I used to pick these from the beach at Telok Paku where they’d burrow into the sand, leaving a tell-tale rectangular hole behind. To catch them, you’d scoop out a good handful of sand around the hole, trapping the shellfish and picking them out, one at a time, until you had a sizeable haul for the pot.

The Malays would cook these snaillike shellfish in a spicy gravy enriched with santan (rich coconut milk), but the Chinese would simply boil them. Also known by the rather rude Malay name “hisap pantat”, literally “suck the backside” because you had to suck the meat out from the bottom of the shells, the cooked shellfish used to be sold by hawkers at the jetty at the end of Ponggol Road. You’d sit on low stools at these stalls to eat the delicacies, boiled in their shells, which the stallholder would serve with a sweet chilli sauce topped with nuts, while enjoying the sea breeze.

Forgotten Fruits

These were idyllic times I enjoyed just as much as I relished the long afternoons spent at the fruit orchards in rural Ponggol. There was a time in the 1960s and early 70s where people could pick their own fruit from these orchards for a fee. You’d pluck off the tree only what you could carry (or eat); the pickings included not only common tropical fruit such as rambutan and mangosteen, but also now hard-to find varieties such as buah pulasan, a rambutan-like fruit with a hard red shell.

Elsewhere on the island, you could find forgotten fruit growing wild, like buah binjai (Mangifera caesia), a cousin to the mango. This is a sour fruit, but there is also a sweet variety – and both smell strongly ambrosial. Just a whiff brings me back to the days of my childhood when lunch could be just fried fish with rice and a fiery sambal made with buah binjai. This fruit is rarely sold commercially these days, but if you go to Binjai Park, the housing estate off Bukit Timah Road that takes its name from the fruit, you should be able to see binjai trees growing along the roadside. A few diehard residents are attempting to plant new trees in the neighbourhood, which was previously a binjai plantation.

Today, few would know what to do with this fruit. Older people would tell you that it can be cooked in a spicy tamarind gravy but is more often served as a dip, mixed with sambal belacan, dark soya sauce and sugar. The same fate could befall other local fruit I used to enjoy during my childhood. They include the sour belimbing (carambola) that my mother used to pickle when in season to add to curries and soups or mashed into a chutney. I still have a tree in my garden and I regularly pickle the fruit, but no one wants it because they don’t know what to do with these belimbing!

Belimbing (carambola) is another fruit that is seldom seen today. It is cooked in a sambal with prawns here. All rights reserved, Tan, S. (2011). Modern Nonya. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Cuisine.

Belimbing (carambola) is another fruit that is seldom seen today. It is cooked in a sambal with prawns here. All rights reserved, Tan, S. (2011). Modern Nonya. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Cuisine.Fewer still would have eaten durian flowers from the durian tree. You fry them with chilli paste or cook it with spices and coconut milk to make a lemak (spicy coconut gravy). The pretty white flowers, which have a short lifespan, fade quickly upon falling. But these days, how many people would have access to a durian tree to pick the fresh flowers anyway?

Then there are the sweet fruit I used to enjoy eating straight off the wayside trees during my youth. Then, a typical afternoon after school could find me picking buah susu, the local passionfruit, to suck out its sweet pulpy juices. Another day, it could be pak kia, the pink-fleshed guava, which was sweeter than the Thai variety – today the only guava sold, it seems. Or buah kedongdong – or buah long long as the Chinese were apt to mispronounce its name – a crunchy and sour fruit that was sometimes sold in its pickled form. Many gardens also had jambu air trees, the smaller local version of the Thai rose apple, which we’d dip into black soya sauce, sliced red chilli and sugar before eating. My mother would regularly pluck terong blandah, a local tamarillo, from our garden to slice and mix with sambal belacan to make yet one more dip with fried fish.

(Left) The writer used to pick pak kia, or guava, from wayside trees on her way home from school. This variety with sweet, pink flesh is rarely found these days. This is one of the paintings that William Farquhar commissioned Chinese artists to do between 1803 and 1818 when he was Resident and Commandant of Malacca. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

(Left) The writer used to pick pak kia, or guava, from wayside trees on her way home from school. This variety with sweet, pink flesh is rarely found these days. This is one of the paintings that William Farquhar commissioned Chinese artists to do between 1803 and 1818 when he was Resident and Commandant of Malacca. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.All these dishes, practices and tastes of bygone years are just distant memories today, and yet they are part of our cultural heritage. Every forgotten food recalls a precious memory of life as it used to be and a history that was shared. It proved that hard times was not a barrier to creativity nor to eating well. How otherwise did we inherit an array of recipes that made good use of less than palatable stuff like offal, innards and snail-like shellfish?

Unfortunately, it was a lifestyle that could not withstand the push towards economic development. Limited land space meant that we stopped growing our own food while universal education saw the rise of the working woman which, unfortunately, led to a narrowing of palates as families stopped cooking altogether. Perhaps it’s time we started preserving our food history by creating an archive of recipes, and by teaching our students in school how to cook these heritage dishes rather than turning out rock buns – the standard primer in domestic science classes three decades ago, and perhaps still today.

Former journalist Sylvia Tan has chalked up nine cookbooks to her name, including Mad About Food, a compilation of her much-loved newspaper columns, Singapore Heritage Food and Modern Nonya. She also writes a regular column, Eat to Live in The Straits Times’ Mind Your Body section. You can follow her on @SylviaTanMadAboutFood

Former journalist Sylvia Tan has chalked up nine cookbooks to her name, including Mad About Food, a compilation of her much-loved newspaper columns, Singapore Heritage Food and Modern Nonya. She also writes a regular column, Eat to Live in The Straits Times’ Mind Your Body section. You can follow her on @SylviaTanMadAboutFood

NOTES

-

Wee, E. H. (2011). Cooking for the president. Reflections & recipes of Mrs Wee Kim Wee. Singapore: Wee Eng Hwa. Call no.: RSING 641,595957 WEE ↩

-

Tan, C. (2015). Nerd baker: Extraordinary recipes, stories & baking adventures from a true oven geek. Singapore: Epigram Books. Call no.: RSING 641.815 TAN ↩