Singapore’s First Japanese Resident: Yamamoto Otokichi

A sailor travels halfway around the world in his attempt to return home, and becomes the first Japanese resident in Singapore in the process. Bonny Tan tells the story.

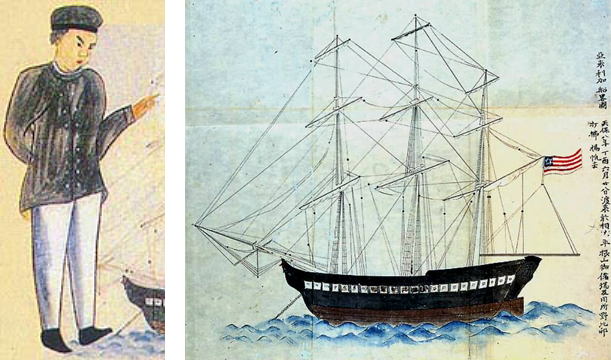

(Left) An 1849 illustration of Yamamoto Otokichi. Artist unknown. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

(Left) An 1849 illustration of Yamamoto Otokichi. Artist unknown. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.During the Edo period (1603–1868) under the rule of the Tokugawa Shogunate,1 Japan was a very insular society and kept its doors closed to foreign influence. Japanese nationals leaving the country could not return home on pain of death, and foreigners were barred from entering the country. Only Nagasaki on southernmost Kyushu island remained open as a primary trading port for the Dutch East India Company. This period of national isolation called sakoku (meaning literally “closed country”) was in force for over 250 years until Commodore Matthew Perry of the US arrived with his fleet in 1853 to wrest open Japan to foreign trade.

An Interlocutor Between East and West

A little known figure by the name of Yamamoto Otokichi – born in 1817 in Onoura in Mihama, Japan – had an important part to play in turning the hinges that eventually opened Japan’s doors to trade with Britain in 1854. As government missions from Japan began travelling out of the country to America and Europe during this period, many would transit in Singapore where Otokichi became their main point of contact. Otokichi, who had moved to Singapore by 1862, was a well-respected member of the Singapore merchantile community and owed his wealth to his close ties with the British.

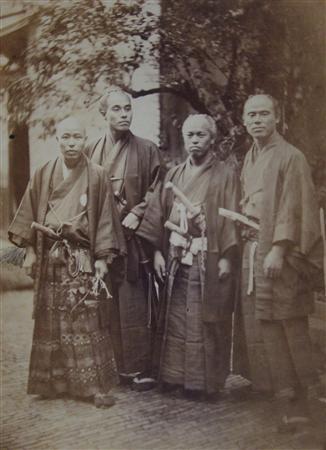

The second overseas Japanese diplomatic mission2 to Europe, led by Takenouchi Yasunori, governor of the Shimotsuke region, arrived in Singapore on 17 February 1862, and stayed here for two days. Among the members of his delegation was the interpreter Fukuzawa Yukichi who would later gain fame as one of the leading advocates for the modernisation of Japan during the Meiji era (1868–1912).

Some members of the Japanese government mission to Europe. Photo taken in Utrecht, Netherlands, in July 1862. The interpreter Fukuzawa Yukichi, who was part of the delegation that visited Singapore earlier on 17 February 1862, is seen standing second from the left. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Some members of the Japanese government mission to Europe. Photo taken in Utrecht, Netherlands, in July 1862. The interpreter Fukuzawa Yukichi, who was part of the delegation that visited Singapore earlier on 17 February 1862, is seen standing second from the left. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.On the day the Japanese entourage arrived in Singapore, Otokichi met up with Yukichi and some members of the mission at the Adelphi Hotel bringing them around Singapore to view the sights, including his house. Yukichi and several others also had their portraits taken at a photo studio on Orchard Road.3

Fuchibe Tokuzo, who visited Singapore a few months later in 1862 as part of a separate mission, captured some aspects of Otokichi’s daily life in Singapore in his journal.4 He described how Otokichi’s two-storey house on Orchard Road with a thatched roof was encircled by a lush garden with abundant trees and flowers. Parked outside the house was a horse cart while the back had a stable along with several outhouses. Helping to run the household were a servant and a maid.

Tokuzo also described the interior of the house. While Otokichi’s son and daughter were upstairs sleeping peacefully, the guests were served tea. Tokuzo had a sharp eye for detail and noted that “all the household furnishings, the plates and cups, etc. were fresh and clean”.5 This was the picture of idyll and success of Singapore’s first Japanese resident as described in the journals of Tokuzo.

The Adventures of Otokichi

Who was Otokichi and how did he end up on this obscure colonial outpost in Southeast Asia? The dramatic story of struggle from obscurity and hardship to eventual victory has the makings of a film. And in fact the story of Otokichi has been captured in a film and a play as well as poetry and song.

In December 1832, the teenaged Otokichi was an apprentice sailor travelling onboard the Japanese cargo ship Hojunmaru. All 14 people onboard the ship were from Otokichi’s fishing village, Onoura, some of whom were his relatives.6 The ship was on a routine journey carrying a shipment of rice and porcelain from port Toba, Japan. While en route to Tokyo, it sailed into stormy waters; a large typhoon tore off the mast and broke the rudder of the ship, leaving the crippled vessel adrift and with no rescue in sight for 14 months as it traversed aimlessly in the Pacific Ocean.

Only three crew members survived the ordeal – Otokichi, then aged 14, and his fellow mates Kyukichi and Iwakichi, aged 15 and 28 respectively. When the trio finally made landfall at Cape Alava in the north-western coast of North America, instead of finding food and shelter, their vessel was plundered by marauding Native Americans and they ended up as prisoners.

Traders from the Hudson Bay Company – at the time a major fur trading company headed by John McLoughlin, the Superintendant of the Columbia District of the company – received word of these castaways and sought to save them. Privately, McLoughlin saw in these Japanese sailors the opportunity to open up Edo Japan to mercantile trade.

When the three Japanese arrived at Fort Vancouver7 in May 1834 after being rescued, they were welcomed with open arms by McLoughlin. After several months of exposure to the Christian faith and some rudimentary English lessons, the Japanese were dispatched to England in the fall of 1834. McLoughlin hoped that the British would bring the men home to Japan and, in the process, establish trade relations with this isolated country.

Otokichi, Kyukichi and Iwakichi arrived in London in June 1835, becoming the first Japanese to set foot in England. However, they were only given one day to tour the city and were otherwise kept confined onboard their ship throughout its entire anchorage in England. When the ship finally set sail about 10 days later for the East, it was at Macau where they landed and not Japan as they had hoped.

In Macau, the trio met Reverend Karl Friedrich August Gützlaff, a linguistically gifted German Protestant missionary who was keen to evangelise the Chinese and translate the Bible into different languages. In the Japanese castaways, he saw the opportunity to translate the scriptures into Japanese. Gützlaff got Otokichi to teach him colloquial Japanese, while in return Otokichi and his comrades received English lessons from his wife Mary Gützlaff at the Macau Free School.

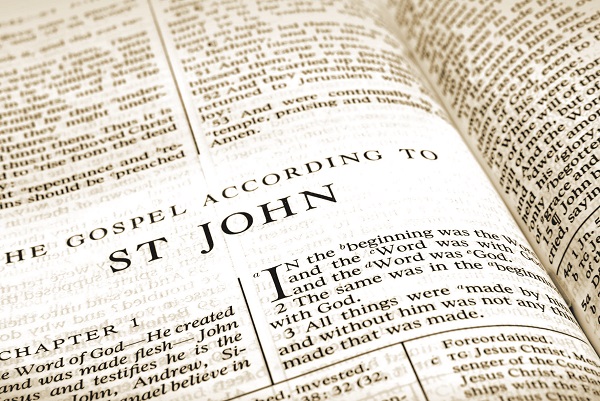

Karl Friedrich August Gützlaff was a 19th-century German Protestant missionary who evangelised to the Chinese and translated the Bible into different languages. All rights reserved, Gützlaff, K. F. A. (1834). A Sketch of Chinese History (Vol. I). New York: John P. Haven. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Karl Friedrich August Gützlaff was a 19th-century German Protestant missionary who evangelised to the Chinese and translated the Bible into different languages. All rights reserved, Gützlaff, K. F. A. (1834). A Sketch of Chinese History (Vol. I). New York: John P. Haven. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.Otokichi is often credited for helping Gützlaff complete the first Japanese-translated portions of the Protestant Bible. The manuscript for “Yohannes’no tayori yorokobi”, or the Gospel of John, written in Japanese katakana script, was subsequently sent to Singapore where it was published by the Mission Press in May 1837. However, in 1838, the American Bible Society put a stop to further print-runs of the publication as the translation was deemed inadequate.8 Copies of this rare publication can be found at the British Library and the Doshisha University Library in Kyoto.

Yamamoto Otokichi was instrumental in helping Reverend Karl Friedrich August Gützlaff, a German Christian missionary, translate portions of the Protestant Bible into Japanese during his time in Macau. The manuscript for “Yohannes’no tayori yorokobi”, or the Gospel of John, written in Japanese katakana script for the first time ever, was subsequently published by Mission Press in Singapore in May 1837. Saint John also figured in Otokichi’s life in other ways: when the latter converted to Christianity, he took on the baptismal name, John Matthew Ottoson. Lane V. Erickson / Shutterstock.com.

Yamamoto Otokichi was instrumental in helping Reverend Karl Friedrich August Gützlaff, a German Christian missionary, translate portions of the Protestant Bible into Japanese during his time in Macau. The manuscript for “Yohannes’no tayori yorokobi”, or the Gospel of John, written in Japanese katakana script for the first time ever, was subsequently published by Mission Press in Singapore in May 1837. Saint John also figured in Otokichi’s life in other ways: when the latter converted to Christianity, he took on the baptismal name, John Matthew Ottoson. Lane V. Erickson / Shutterstock.com.At some point, Otokichi converted to Christianity, taking on the baptismal name John Matthew Ottoson, likely inspired by his work on the Gospel of John. Otokichi’s luck subsequently turned when the American businessman Charles King invited Otokichi to board the Morrison on 4 July 1837 headed for Japan. However, as the ship entered Edo Bay on 30 July, it was met with unexpected cannon fire instead of a warm welcome. Japan was not ready to receive foreigners or returning Japanese who had been exposed to the “evils” of Western influence and foreign culture.

Crushed by this response, Otokichi and his comrades shaved their heads in a symbolic act to protest against their mistreatment and indicate that they would henceforth turn their backs on Japan. Thanks to his unique position, however, Otokichi continued to play the role as interlocutor between the East and the West, a task that would continue to grow in importance in the ensuing years.

In the meantime, China had preceded Japan in opening up its ports to trade. The opening of five treaty ports in China in 1842 saw Otokichi settling in Shanghai, where he gained employment at Dent and Co., a trading company that made a name for itself from China’s open trade with Britain. Otokichi was soon put in charge of the warehouse at Dent and Co. While in Shanghai he met and married Louisa Brown, his second wife, who was of Malay and German ancestry and had family links in Singapore. He soon acquired a working knowledge of Chinese and even adopted a Chinese name, Lin Ah Tao.

At the same time, British agents continued to use Otokichi as an interpreter in their several attempts to establish trade with Japan. In 1854, soon after Commodore Matthew Perry of the US Navy had forcibly opened Japan to American ships, the British Admiral James Stirling engaged Otokichi’s help to serve as a translator to negotiate the opening of the port of Nagasaki to England. This time around, the Japanese Shogunate extended an olive branch by inviting Otokichi to return to Japan.

Still seething from his earlier rebuff, Otokitchi refused, choosing instead to take up British citizenship. This was Otokichi’s reward from the British for his part in the negotiations along with a handsome monetary reward, which he used to relocate his family from Shanghai to Singapore where he purchased land.

Otokichi in Singapore

Although most biographies of Yamamoto Otokichi note that he was a resident in Singapore from 1862 onwards, Leong Foke Meng’s 2005 book The Career of Otokitchi claims that the Japanese had visited Singapore as early as the late 1840s. Otokichi had helped Gützlaff purchase land in Singapore in May 1849 for the burial of the latter’s first wife, Mary.

By the late 1850s, Otokichi had decided to leave Shanghai, then in the throes of the Taiping Rebellion, for Singapore. Leong carefully traces paperwork which shows that Otokichi had resided initially on Queen Street before moving into one of the largest houses in Orchard Road, nestled in the midst of a vast nutmeg and clove plantation. In 1862, Otokichi’s four-year-old daughter, Emily Louisa Ottosan, by his first wife,9 died prematurely and was buried in Fort Canning Cemetery.

Otokichi eventually died of tuberculosis at Arthur’s Seat, a sanitarium in the Siglap area on 18 January 1867,10 at age 50, and his remains were buried at the Bukit Timah Christian Cemetery. His wife Louisa, who bore him two daughters and a son, subsequently remarried and took on the name Belder.

The memorial to Yamamoto Otokichi, containing some of his cremated remains, at the Japanese Cemetery Park in Singapore. Photo by Aldwin Teo. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The memorial to Yamamoto Otokichi, containing some of his cremated remains, at the Japanese Cemetery Park in Singapore. Photo by Aldwin Teo. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.Nothing more was heard about Otokichi until enquiries were made in Singapore as early as 1937 on the whereabouts of his grave. In the 1960s, enquiries made by the Japanese Bible Society about Otokichi later sparked interest in his hometown of Mihama in Aichi Prefecture.

Otokichi’s townsfolk first visited Singapore in 1993 and the following year, a musical on Otokichi’s life was performed at the Victoria Theatre. On 17 February 2005, the Mayor of Mihama, Koichi Saito, and his 120-strong entourage left Japan for Singapore with the intention of bringing Otokichi’s remains back to his hometown. Their departure coincided with the date that Otokichi had called upon the aforementioned Fukuzawa Yukichi exactly 143 years ago when the Japanese diplomatic mission enroute to Europe arrived in Singapore. As a gift to Singapore, the Mihama delegation performed Otokichi Beat, a song specially composed in his memory, at the Chingay parade that year.

Otokichi’s remains were subsequently exhumed and cremated, and his ashes put into three urns. One urn was placed at the Japanese Cemetery at Hougang, while the other two were brought back to Japan. One urn was sent to Ryosanji Temple in Onoura, Otokichi’s birthplace in Mihama, where gravestones had been laid in memory of the sailors on the ill-fated Hojunmaru. The last urn was given to Otokichi’s only known descendant, Junji Yamamoto, related through Otokichi’s younger sister.

The remains of Otokichi Yamamoto were finally laid to rest in his place of birth – 173 years after the intrepid 14-year-old had set sail from Japan on an unexpected adventure that took him halfway around the world.

The author would like to thank Mr Leong Foke Meng and Mr Akira Doi for reviewing this article.

Bonny Tan is a former Senior Librarian at the National Library, Singapore. She currently resides in Vietnam with her family and is a regular contributor to BiblioAsia magazine.

Bonny Tan is a former Senior Librarian at the National Library, Singapore. She currently resides in Vietnam with her family and is a regular contributor to BiblioAsia magazine.REFERENCES

Akira, D. (2007). Pioneers of Japanese bible translation: The application of the dynamic equivalent method in Japan [Masters of Arts in Japanese thesis, Massey University, New Zealand]. Retrieved from Massey Research website.

Beasley, W.G. (1995). Japan encounters the barbarian. New Haven: Yale University Press. (Call no.: RUR 327.52 BEA)

Cobbing, A. (1998). The Japanese discovery of Victorian Britain: Early travel encounters in the Far West. Richmond, Surrey: Japan Library. (Call no.: RUR 914.204 COB)

Kohl, S.W. (1982, January). Strangers in a strange land: Japanese castaways and the opening of Japan. The Pacific Northwest Quarterly, 73 (1), 20–28. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

Kwan, W.K. (2005, February 17). Japanese sailor going home after 173 years. The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Leong, F.M. (2005). The career of Otokichi. Singapore: Heritage Committee, Japanese Association Singapore. (Call no. : RSING 959.5703092 LEO)

Leong, F.M. (2012). Later career of Otokichi. Singapore: Heritage Committee, Japanese Association Singapore. (Call no. : RSING 959.5703092 LEO)

Lim, S.B. (Ed.). (2004). Images of Singapore: From the Japanese perspective (1868–1941). Singapore: The Japanese Cultural Society. (Call no. : RSING 959.57 IMA)

Mockford, J. (1991). The open gate of Fort Vancouver: Japan-America relations in early Pacific Northwest History. Clark County History, 32.

National Library Board. (2016). Yamamoto Otokichi written by Tan, Bonny. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website.

Notes of the day. (1937, May 17). The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Plummer, K. (1991). The shogun’s reluctant ambassadors: Japanese sea drifters in the North Pacific. Oregon: The Oregon Historical Society. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Prewar Japanese community in Singapore: Picture and record [Senzen Shingapōru no Nihonjin shakai: Shashin to kiroku]. (2004). Singapore: Japanese Association. (Call no. : RSING 305.895605957 PRE)

Tei, A.G., & Igarashi, Y. (2010). True life adventures of Otokichi(1817–1867) . Retrieved from JM Ottoson website.

NOTES

-

The shogunate was officially established in Edo on 24 March 1603 by Tokugawa Ieyasu. The Edo period came to an end with the Meiji Restoration on 3 May 1868. ↩

-

The first overseas Japanese mission visited America in 1860 and proved successful in building international ties. The second overseas mission was sent to Europe in 1862 with about 35 to 40 members in the entourage. En route, they stopped at British ports such as Hong Kong and Singapore. ↩

-

Leong, F.M. (2012). Later career of Otokichi (pp. 7–9). Singapore: Heritage Committee, Japanese Association Singapore. (Call no. : RSING 959.5703092 LEO) ↩

-

Fuchibe, T. (1972). Oko nikki [Journal of a trip to Europe] in Kengai shisetsu nikki sanshu [An anthology of diaries of a mission sent abroad]. Ed. Nihon Shiseki Kyokai (Vol. 98, pp. 18–19). In Kohl, S.W. (1982, January). Strangers in a strange land: Japanese castaways and the opening of Japan. The Pacific Northwest Quarterly, 73 (1), 20–28, p. 27. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

The village men raised a tombstone at the family temple in memory of the 14 they presumed had passed away that fateful day. See Plummer, K. (1991). The shogun’s reluctant ambassadors: Japanese sea drifters in the North Pacific (p. 248). Oregon: The Oregon Historical Society. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

In the 19th century, Fort Vancouver was a fur trading outpost along the Columbia River. It served as the headquarters of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Columbia Department. ↩

-

Akira, D. (2007). Pioneers of Japanese bible translation: The application of the dynamic equivalent method in Japan (pp. 61–63). [Masters of Arts in Japanese thesis, Massey University, New Zealand]. Retrieved from Massey Research website. ↩

-

There is no record of the name of his first wife although she is believed to be English. ↩

-

Death date of 18 January 1867 is derived from Leong, 2012, p. 11, which references Singapore Daily Times, 21 January 1867. ↩