Building Faith: Wartime Churches in Syonan-to

Christian POWs interned during the Japanese Occupation found ingenious ways to worship. Gracie Lee looks at a book documenting these makeshift churches in war-torn Singapore.

A painting of a church service by William Haxworth, 1942. Haxworth was the Chief Investigator of the War Risks Insurance Department of the Singapore Treasury when the war broke out. He was subsequently interned by the Japanese, first in Changi Prison and then at Sime Road Camp. He secretly drew over 300 small paintings and sketches that depicted the harsh and cramped living conditions in these POW camps. W R M Haxworth Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A painting of a church service by William Haxworth, 1942. Haxworth was the Chief Investigator of the War Risks Insurance Department of the Singapore Treasury when the war broke out. He was subsequently interned by the Japanese, first in Changi Prison and then at Sime Road Camp. He secretly drew over 300 small paintings and sketches that depicted the harsh and cramped living conditions in these POW camps. W R M Haxworth Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.heavy laden, and I will give you rest.”

– Matthew 11:28

Published in Britain in 1946, The Churches of the Captivity in Malaya was written by the Assistant Chaplain General of the Far East, Reverend John Northridge Lewis Bryan,1 to show how churches provided “spiritual and moral uplift” to Christian Allied soldiers interned in prisoners-of-war (POW) camps in Singapore during the Japanese Occupation (1942–45).

The 72-page book, released a year after the end of World War II, chronicles 20 churches, a synagogue, a memorial altar, a memorial cross and a cemetery that were established by POWs in Singapore and elsewhere. It is beautifully illustrated with 27 watercolour paintings, black-and-white sketches and photographs contributed by ex-internees. Short descriptions of each church accompany the illustrations.

The book, containing a foreword by Frederick L. Hughes, Chaplain-General to the British forces, and an introduction by Major-General Arthur E. Percival, Commander-in-Chief of the Malaya Command, serves as a valuable historical and visual record of the many churches that were built, dismantled, moved and rebuilt by POWs during the three-and-a-half years when Singapore was known as Syonan-to (Light of the South).

It is a handy resource that complements the numerous oral and written accounts on individual POW experiences. The book was in fact used to identify the artist of the Changi Murals, Stanley Warren, when the paintings were “re-discovered” in 1958. It was also used by the Singapore Tourist Promotion Board (now Singapore Tourism Board) in the design of the Changi Chapel during the 1980s.

While the Changi Murals in the former St Luke’s Chapel in Roberts Barracks and the Changi Chapel2 at the Changi Museum are the two most recognisable ecclesiastical POW sites in Singapore today, this book reminds contemporary readers that there were many more of such churches built by POWs during the Japanese Occupation. Only a small fraction of these – many of which were rough makeshift places – are represented in this book.

This book also provides a useful overview of the organisation, design and evolution of POW churches, which emerged shortly after the fall of Singapore in February 1942. These churches were sanctuaries that provided spiritual support and hope to internees who suffered from starvation and oppression under the Japanese Imperial Army. Bonded by a common purpose, internees from various Christian denominations, ranks and nationalities pitched in to build churches at detention camps in Changi, Sime Road, Adam Park and elsewhere in Singapore.

The resourceful POWs managed to achieve much with the little they had, and came up with ingenious ways to hold church services. Some churches were adapted from the ruined remains of buildings or erected from salvaged materials, while others were simply open-air assemblies that were spartanly furnished with handmade furniture. Some of the more unusual places include a rifle-range, cinema, garage and even a refrigeration building.

Church altars were designed by POWs who were trained architects, and Christian paraphernalia and furniture were fashioned from a motley assortment of materials. For instance when candles were no longer available, light bulbs from torches were mounted onto candlesticks and powered by electricity. Flower vases were made from shell cases, candlesticks from ladies’ hatstands, and choir stalls from the swinging doors of bungalows. Internees who laboured outside the camps picked wild flowers for the altar. The bread eaten during the Holy Communion rite3 was made from rice flour, maize flour or tapioca, while watered down blackcurrant jam, boiled raisins and even gula melaka (palm sugar) were used in place of wine.

Time and again, POWs were forced to abandon these makeshift churches when the Japanese authorities evacuated camps or redeployed POWs to other detention sites. Undeterred, the internees started new churches wherever they went even as their freedom was curtailed as the Occupation continued and the atrocities they suffered increased over time.

Here are examples of some POW churches featured in the book.

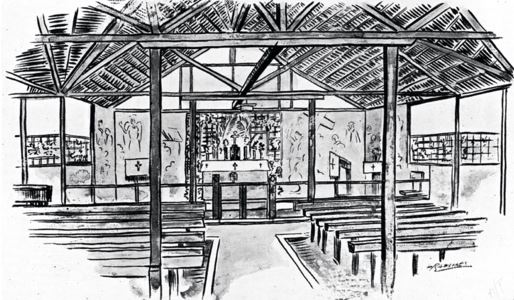

St David’s Church was erected to minister to the internees at the Sime Road POW camp. The wall murals on either side of the altar were created in charcoal by Stanley Warren, best known as the painter of the Changi Murals at St Luke’s Chapel at Roberts Barracks. The mural to the right of the altar depicted the scene from the “Nativity”, while the one on the left featured the scene from “The Descent from the Cross”. Today, a power substation occupies the site of the former St David’s Church.

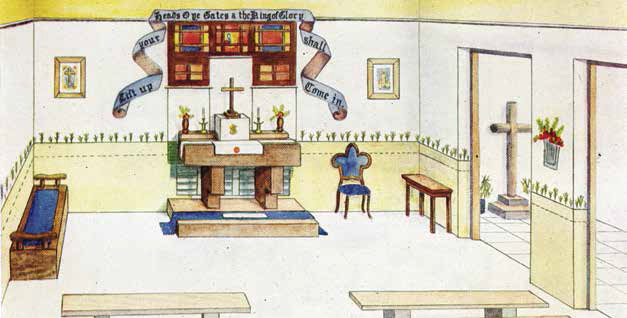

Adam Park Church (also known as St Michael’s Chapel) was established on the upper floor of a bombed house in Adam Park (now No. 11 Adam Park) and opened on Pentecost Sunday on 24 May 1942. The altar cross was taken from the mortuary chapel at Alexandra Hospital, and the stained glass windows above the altar were constructed from glass pieces and transparent paper. In April 2016, the press reported the discovery of the remains of the church’s wall murals with the Bible verse, “Lift up your heads, O ye Gates and the King of Glory shall Come in”. The murals were drawn by Captain Reverend Eric Andrews, the camp interpreter and padre, using yellow clay and Reckitt’s Blue4. Adam Park served as a POW camp during the Japanese Occupation.

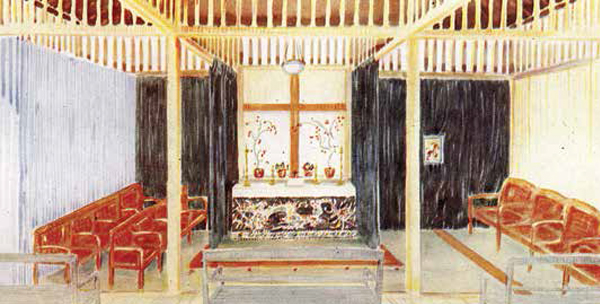

In April 1942, many POWs were dispersed to camps around the island. One such camp was set up at the Great World Amusement Park. To meet the spiritual needs of the servicemen, the Church of the Ascension at Great World opened on Ascension Day on 14 May 1942. The church was formed by combining four shop units, including a Chinese beauty parlour. Furnishings were scoured from empty shops in the amusement park and adapted for use. This may explain the hint of chinoiserie present in the interior of the church.

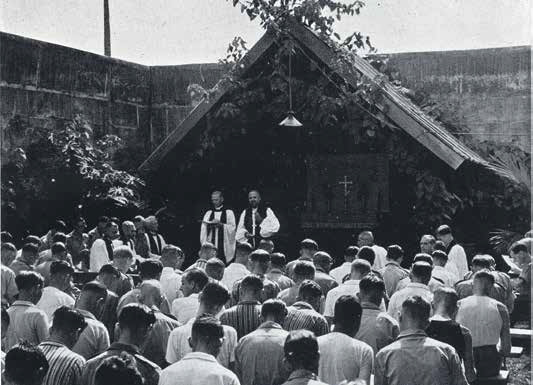

The architecture of St George’s Church, located near the Changi Gaol, is typical of open-air POW churches of the time. Built in 1944, this was the third iteration of St George’s Church – the first was near Changi Village and the second in Kanburi (or Kanchanaburi), Thailand. In this particular construction, the church had a rudimentary “A” frame roof measuring 14 ft by 10 ft that functioned as a chancel and shelter for the altar. On the altar was a brass cross, known as the Changi Cross. It was fashioned from a 4.5 Howitzer shell in 1942 and followed the church during its various relocations. The rest of the church was exposed to the elements and enclosed only by an attap fence. The church also had permanent benches that could seat 200 people. Shrubs, creepers and tropical flowers were planted to beautify the sanctuary. In April 1945, the church moved for the fourth and last time to the officers’ area of Changi Prison. The altar cross currently resides at the Changi Museum.

St Paul’s Church, which opened in June 1944, was constructed inside Changi Gaol, between the Punishment and Isolation blocks. The pulpit, altar rails, lectern, cross and memorial tablets were recycled from the dismantled churches in the Selarang area. The church was the venue for the first Confirmation5 service after the liberation of Singapore in September 1945.

All images are from The Churches of the Captivity in Malaya by John Northridge Lewis Bryan and published by the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (1946). The author wishes to thank the society for granting permission to reproduce the images in this article.

Gracie Lee is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. She works with the Rare Materials Collection, and her research areas are in colonial administration and Singapore’s publishing history.

Gracie Lee is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. She works with the Rare Materials Collection, and her research areas are in colonial administration and Singapore’s publishing history.

References

Amstutz, H. B. (1945). Prison camp ministries: The personal narrative of Hobart B. Amstutz, 17 February 1942 to 7 September 1945. Singapore: Wesley Manse. Call no.: RRARE 940.5478 AMS; Microfilm no.: NL 10071

Australian Government, National Capital Authority. (2013, March 19). Changi Chapel. Retrieved from National Capital Authority website.

Blackburn, K. (2015). The ghosts of Changi: Captivity and pilgrimage in Singapore. In K. Reeves, et. al. (Ed.), Battlefield events: Landscape, commemoration and heritage (pp. 144–163). Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Bryan, J. N. L. (1946). The churches of the captivity in Malaya. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. Call no.: RCLOS 940.5472595 BRY

Chua, S. K., & Tan, B. L. (Interviewers). (1983, September 21). Oral history interview with Mr Stanley Warren [Transcript of MP3 Recording No. 000205/08/06, pp. 54–55]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website.

Chua, S. K., & Tan, B. L. (Interviewers). (1983, September 22). Oral history interview with Mr Stanley Warren [Transcript of MP3 Recording No. 000205/08/08, p. 78]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website.

Cooper, J. (n.d.). Report on investigation of hidden mural at No. 11 Adam Park & hidden calendar at No. 5 Adam Park. Retrieved from Adam Park Project website.

Cooper, J. (2016). Tigers in the park: The wartime heritage of Adam Park. Singapore: The Literary Centre. Call no.: RSING 940.547252095957 COO

Cordingly, L., & Waite, T. (2015). The Changi cross: A symbol of hope in the shadow of death. Norwich: Art Angels Publishing. Call no.: RSING 940.5472520922 COR-[WAR]

FEPOW Community. (n.d.). Reverend L V. Headley. Retrieved from FEPOW Community website.

Hamzah Muzaini & Yeoh, B. S. A. (2016). ‘Localising’ war representations at the Changi Chapel and Museum. In Contested memoryscapes: The politics of Second World War commemoration in Singapore (pp. 47–68). Farnham, Surrey, England: Ashgate. Call no.: RSING 940.546095957 MUZ-[WAR]

Hayter, J. (1991). Priest in prison: Four years of life in Japanese-occupied Singapore, 1941–1945. Thornhill: Tynron. Call no.: RSING 940.547252092 HAY

Headley, G. (2009, March 10). The work of the church in the Japanese jail camps. Retrieved from From Harlech & London website.

Imperial War Museums. (2016). Scenes in Changi prisoner-of-war camp, Singapore 1942. Retrieved from Imperial War Museums website.

Stubbs, P. W. (2003). The Changi murals: The story of Stanley Warren’s war. Singapore: Landmark Books. Call no.: RSING 940.547252092 STU

Tan, B. L. (Interviewer). (1983, June 20).Oral history interview with Carl Francis de Souza [Transcript of MP3 Recording No. 000290/07/01, pp.1–3, 7–11]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website.

Tan, B. L. (Interviewer). (1983, June 20). Oral history interview with Carl Francis de Souza [Transcript of MP3 Recording No. 000290/07/02, p. 14]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website.

The Adam Park Project. (2016, May 22). Captain Eric Andrews – St Michael’s Chapel, Adam Park, Choral Register and Congregational Roll p. 285. Retrieved from Adam Park Project website.

Zaccheus, M. (2016, April 11). WWII tale unravels at Adam Park bungalow. The Straits Times. Retrieved from The Straits Times website.

Notes

-

Bryan, J. N. L. (1946). The churches of the captivity in Malaya. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. Call no.: RCLOS 940.5472595 BRY ↩

-

The open-air Changi Chapel in the Changi Museum is a representative replica of the many chapels that were built by POWs during the Japanese Occupation. It is often mistaken to be an exact copy of an original war-time chapel, also named the Changi Chapel, at the Royal Military College in Canberra, Australia. The chapel in Australia was first built in 1943 at Sime Road Camp and re-assembled by Australian forces at Changi Camp in 1944. After the war, the chapel structure was dismantled and taken to Australia. In 1988, it was restored as a memorial to Australian POWs. In contrast to the chapel in Australia, Changi Chapel in Singapore is a simpler structure made from wooden planks with a high “A” frame roof covered with attap (palm) leaves. Its thatched hut design is an archetype of the many make-shift open-air churches built at the time. ↩

-

Holy Communion is a Christian sacrament in which consecrated bread and wine are partaken as the body and blood of Jesus Christ or as symbols of Christ’s body and blood in remembrance of Christ’s death. ↩

-

Reckitt’s Blue is a laundry whitener that contains traces of blue dye. ↩

-

Confirmation is a Christian sacrament or rite where adolescents or adults, having been baptised as infants and now reached the age of reason, affirm their Christian beliefs and become a full member of the church. ↩