The Sook Ching

February 15 marks the 75th anniversary of the fall of Singapore. Goh Sin Tub recounts the horrors that many Chinese suffered at the hands of the Japanese in this short story.

In December 1941, just as I turned 14, World War II descended on us in Singapore. Our family was then living in a shophouse on peaceful Emerald Hill, which suddenly became no longer peaceful, indeed more like a battlezone. Our neighbourhood was close to Monk’s Hill, an anti-aircraft artillery site and therefore a target of enemy air attack. The din of that aerial bombardment so near was nerve-racking. We packed a few bags and fled off to Granduncle’s house, a relatively safe storehouse-cum-residence in Philip Street in the centre of town.

Then, on 16 February 19421 (Chinese New Year’s Day of that year!), to our shock and dismay, the British capitulated and the Japanese army marched in.

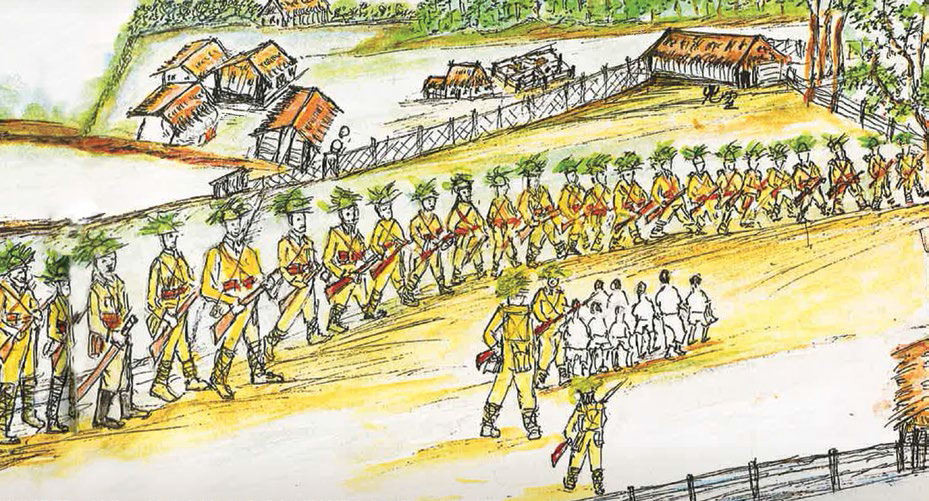

On 17 February, our new masters issued their first public order in Singapore, now called Syonanto: all male Chinese adults were to report the very next day at designated camps – under threat of “severe punishment”, a phrase quickly to become familiar. Most of us presumed then it was only for some kind of registration of people.

But those concentrations of the Chinese were actually for a sinister purpose.

The conquering Japanese troops had arrived with horrendous baggage: memories of bloody encounters with the mainland Chinese in the still ongoing Sino-Japanese war. And they were sorely aware that the Chinese in Singapore had been anti-Japanese, staging demonstrations, organising boycotts of Japanese goods and raising money (the China War Relief Fund) to help the Chinese on the mainland in their fight against invasion. And there were the Singapore Chinese who took up arms against the Japanese: volunteers with the British forces as well as those MCP (Malayan Communist Party) diehards, who struggled against them in the jungles of the Malay Peninsula.

Led by the ruthless Kempeitai (Japanese Military Police), the victorious soldiers went all out to screen the Chinese, however hasty and slapdash the operation, to seek and destroy anyone suspected of being hostile, no matter how flimsy the evidence, no matter how many were fingered. This operation was their infamous Sook Ching – a haphazard sudden horror that slaughtered possibly up to 50,000 Singapore people.2 Indeed there were few Singapore Chinese families who did not lose one or more relatives in that massacre, without doubt the darkest hour in our history.

The day the Allied troops left was the signal for instant lawlessness and chaos in the streets. My father saw how looters, our own local people, went on a rampage, breaking into vacated shops and homes everywhere. He became anxious about our own home that we had left unguarded. Not knowing how bloodthirsty and trigger-happy the occupying soldiers were, he rashly decided to rush back home instead of reporting to the Maxwell Road camp designated for our area. He would not risk the whole family going back with him, but he agreed to take along Sin Chan, my 16-year-old elder brother.

We were to remain ignorant till days later about what happened to Father and Sin Chan after they left the safe haven of Granduncle’s house.

Meanwhile, Granduncle took charge of me. Together with his own son and his workers (whom he had always treated like family members, even to the extent of providing them with meals and shelter in his home), he took us to report at the Maxwell Road camp.

The camp was an unforgettable experience, although we were only there overnight. At the barricaded entrance of the camp, we came face to face with the ugly face of the enemy: uncouth and aggressive Japanese soldiers, yelling loudly and brandishing bayoneted rifles at us, clearly straining to be given cause to stab or shoot us. Indeed, we could hear screams now and then – and we could see bodies lying around, whether dead, ill or asleep we did not know. As we stepped around the screened entrance into the open area of the camp, we were hit with a shocking scene: a panoramic sea of anxious faces. Fear, palpable as heartbeats of panic, in all eyes. Frightened faces wherever we looked. And into that quagmire of terror-stricken humanity we were at once engulfed, with that sinking sensation of being sucked in, identity lost, now part of the world of the helpless and the damned…

For hours we stayed in that hell-hole, squatting around in tight huddles, doing nothing, on the edge of hysteria from not knowing our fate. We were shoved into queues. Then hurried forward, one by one. It was followed by more waiting outside a makeshift tent. Soon, we were standing there before our judges and executioners: a screening panel of unfriendly soldiers and interpreters. This included some strange men who had their faces hidden behind hoods and spoke only in whispers but did a lot of pointing with their fingers.

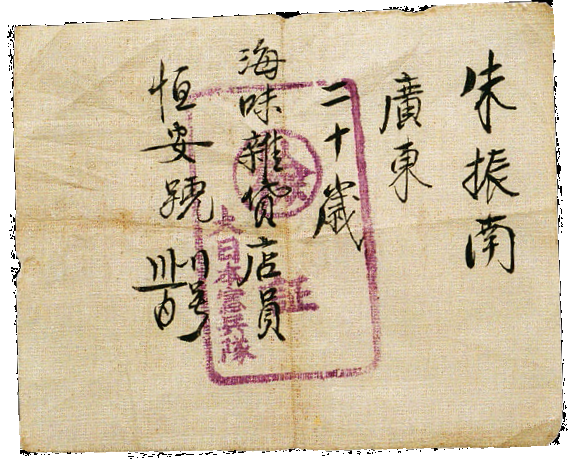

Those of us cleared after questioning were given slips of paper chopped with a seal. When they ran out of paper, they would stamp those cleared on their shirts or arms. These chops had to be preserved at all costs. Over the coming days they would be lifesavers: precious proof of screening clearance whenever Japanese soldiers checked us on the streets or came to search our homes.

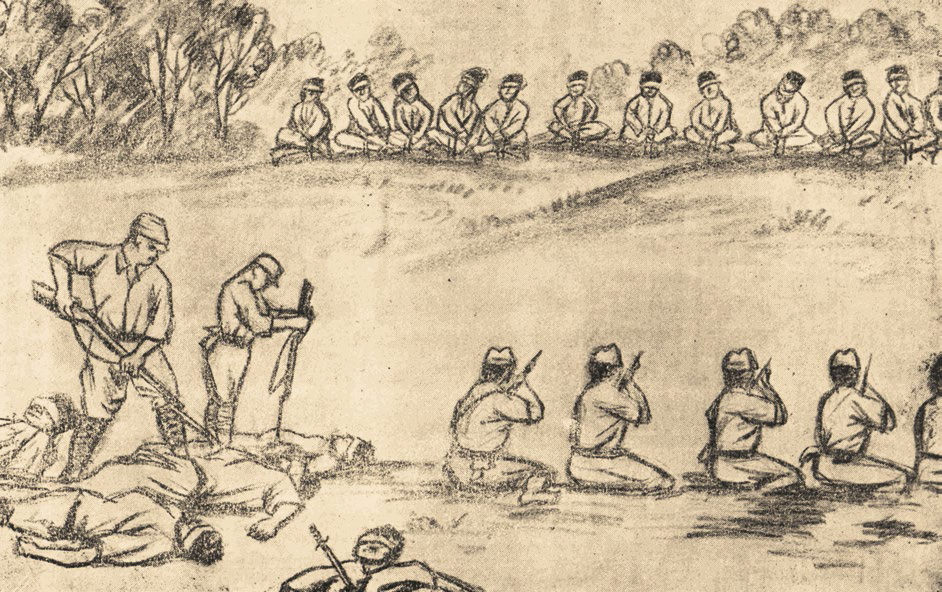

Here and there, someone before that inquisition team would be dragged off and made to squat in a cordoned group below the hot sun under the surveillance of soldiers with guns vigilantly trained on them.

We thought they were people needing further screening or selected to do some work or other. We did not know that they were the ones who would never go back home.

Granduncle took up the rear of our family group in the queue. I think he wanted to make sure that all his family got through that Sook Ching filter. We did – all of us. He did not.

A clueless teenager who had grown up as a sheltered child, I stood wide-eyed and quavering like jelly before those Japanese inquisitors. That helped me. I was clearly not worth their wasting time on. An interpreter passed me a stamped slip and told me to scram. I quickly stepped out into the open street.

Granduncle had given me strict instructions. Don’t hang around outside the camp once you’re out of it. Don’t wait for the rest of our group. That could be dangerous.

So at once I took to my heels, heading for our Philip Street home. The trouble was that I was such a wimp and literally not streetwise at all. I did not know my way around that Chinatown neighbourhood. I got lost and wandered about the streets, getting more and more confused and frightened. I must have been going around in circles for hours. There was nobody around I could ask for help. Everyone was either still in the camp or locked up behind their own closed doors. The few I saw, perhaps like me screened and released, were in desperate hurry to get out of the streets – no one had time for a lost kid.

That was one of those times when the grace I received from school education by the Christian Brothers taught me what to do. I prayed.

And my prayer was answered.

I heard someone calling out to me. It was Yeo Tian Chwee, one of Granduncle’s young workers. He too had been cleared. He had headed for the safety of home at once. When he found out that I was missing he bravely went back into the streets to search for me.

We reached home safely. Someone told us that although everyone else was back, Granduncle was still not home yet. Tian Chwee immediately took to the streets again to find out what had happened to him. He did not return till he had to – it was getting dark and the Japanese had imposed curfew after dark. He came home with sad news. Someone had seen Granduncle: he was one of those pushed into the packed trucks that took away the uncleared…

Grandaunt cried but she never gave up hope. The days of Granduncle’s not coming home stretched into weeks, then months, then years…

And the vultures came, always bringing hope, always needing to be paid to get more news, devouring the old lady, flesh and spirit, till she became a shadow of her old happy self. Till she wept those lovely eyes of hers hollow and blind.

Tian Chwee, thankfully saved from that Sook Ching purge, remained a mainstay of the family, marrying the daughter of his boss, managing the family business, looking after the old lady and the rest of the family and workers.

For myself, Sook Ching was the purge of my childhood innocence. It was my first encounter with evil…

What of my father and Sin Chan?

We were worried sick about them. They had disobeyed the Japanese authorities’ order: they had not reported to their designated screening camp. Both had no saving chop to safeguard them from detention (or a worse fate) if caught without that precious proof of clearance. So we thought. Actually, both had also gone through another Sook Ching camp.

My brother had been cleared.

My father had not… but lived.

Where were they? What to do? We could only pray – my mother with her calming joss-sticks (she was not a Christian then), I with the powerful prayers the Christian Brothers had taught me.

Suddenly, they turned up at Philip Street – with a harrowing story of hide-and-seek, and running for dear life, and finally escaped from the Japanese.

The day they set out they had to pass through Japanese barricades but they reached our Emerald Hill home safely. They found the house all right – or almost all right, as the house adjoining ours had been partially devastated by a bomb that totally demolished the house next to it on the other side!

They had no food and had to depend on the charity of neighbours.

The soldiers came frequently to search all the houses. On one occasion there was a peremptory knocking, and just as Sin Chan opened the door a bayonet was impatiently thrust in. My brother felt the coldness of steel right next to his cheek – a chilling experience he recalls up to this day.

The people of Emerald Hill were ordered to report for screening. They were to assemble at Ord Road, not far off. Father and Sin Chan packed food and other necessities on to a bicycle which they pushed along. They did not get far. Their bicycle was spotted by Japanese soldiers and snatched away from them – everything on it too!

They reached Ord Road where they stayed for two days. Fortunately, there were good people around who shared food with them. From Ord Road they were made to march to Arab Street where their Sook Ching camp was situated. At Arab Street, Father was relieved to spot a friend who had a crockery shop there. He gave food and shelter to Father and Sin Chan while they waited for their screening the next day.

Sin Chan was lucky. He was quite dark-complexioned then. That fact might have saved his skin as he looked like a Malay – without any fuss they cleared him stamping him on the hand with their precious chop.

Yes, he was lucky. He recalled a school cadet corps friend of his, fit-looking like him – the young man stupidly came to that same camp wearing his military-looking cadet boots. He did not make it out of the camp.

Father, tall and athletic-looking, was fingered too. He was roughly pulled aside and made to squat on the roadside with others in a group guarded by soldiers – those not given stamps of clearance.

His immediate concern was for his son. He at once yelled to him: “Don’t worry. Just go to my friend’s house. Stay there. Wait for me to come back!”

How could Sin Chan not worry? But what else was there to do? He obeyed Father and went to the crockery shop to wait.

Father later told Sin Chan what happened to him. He saw trucks coming along to pick up those in the squatting group. He knew then he had to get out of there. He noticed a monsoon drain near where the trucks were lined up. He delayed climbing up on to the trucks. He waited for his chance when the guards were not looking. That chance did not come till the very end when he was the last man in the group: he then slipped quietly into the drain. He hid till everyone had gone. Then he climbed out and made his way to his friend’s shop not far off.

Miraculously, Father had escaped the Sook Ching!

Father and Sin Chan decided to find their way to Philip Street. They had to hide and watch what was going on ahead of them in case they came upon any barrier. Where they found people being checked for clearance chops they had to find other routes – as Father did not have clearance. They came upon scenes of people being made to kneel on the roadside for hours. Those people were hit with the butts of rifles. Prudently, Father and Sin Chan stayed away from those roadblocks.

Finally, at River Valley Road near the old Great World Amusement Park, they found a sandbag wall that they thought was unguarded. As it was getting dark they thought they could take a chance and climb over the barrier.

Father climbed over to the top. He reached out with his hand to help Sin Chan over.

At that moment their world nearly came to an end. There were soldiers around! These yelled out at them: “Kora!” and more – words they did not understand. They were not about to stay and find out what that was about. They continued their run from the wall. One soldier opened fire. But they were already over – and running off as fast as their legs could carry them. Luckily, the soldiers decided not to give chase.

Our family reunited, we decided to play it safe and not test any barricade till the need for stamped clearances was over.

We stayed on at Granduncle’s place for many days after that till the dust stirred up by that first wave of savage Japanese invaders had settled down. The barricades were removed, and it was less hazardous to make our homeward journey to Emerald Hill.

The nightmare of that “purification through purge” has passed into history – unforgettable history.

For me personally, Sook Ching was no “purification through purge”. Yes, my guilelessness had been purged – but Sook Ching was also impurification for me: my initiation, into the reality of a hard and cruel world.

Illustration and handwritten note by the artist Ma Jun (马骏) describing the display of severed heads at the Cathay Building on 6 July 1942. All rights reserved, Tan, S. T. L., et. al. (2009). Syonan Years 1942–1945: Living Beneath the Rising Sun. Singapore: National Archives of Singapore.

Illustration and handwritten note by the artist Ma Jun (马骏) describing the display of severed heads at the Cathay Building on 6 July 1942. All rights reserved, Tan, S. T. L., et. al. (2009). Syonan Years 1942–1945: Living Beneath the Rising Sun. Singapore: National Archives of Singapore. Goh Sin Tub (1927–2004) wore many hats in his lifetime – as teacher, social worker, high-ranking civil servant, banker and property developer, and also as chairman of the Board of Governors at St Joseph’s Institution. Although he had been writing since his school and university days, he only pursued it seriously after his retirement in 1986. Although Goh was a prolific writer of short stories, he also wrote poetry and two noteworthy novels. In all, he published 20 books during his two-decade-long writing career, mainly about Singapore and its struggles during its transformative years.

Goh Sin Tub (1927–2004) wore many hats in his lifetime – as teacher, social worker, high-ranking civil servant, banker and property developer, and also as chairman of the Board of Governors at St Joseph’s Institution. Although he had been writing since his school and university days, he only pursued it seriously after his retirement in 1986. Although Goh was a prolific writer of short stories, he also wrote poetry and two noteworthy novels. In all, he published 20 books during his two-decade-long writing career, mainly about Singapore and its struggles during its transformative years.

Notes

-

According to official accounts, Singapore fell to the Japanese on 15 February 1942. The British surrender took place at the old Ford Factory in Bukit Timah, where the Japanese had set up their headquarters. ↩

-

Following the fall of Singapore on 15 February 1942, Chinese males between 18 and 50 years of age were ordered to report to designated centres for mass screening. Many of these ethnic Chinese were then rounded up and taken to deserted spots to be summarily executed. This came to be known as Operation Sook Ching (the Chinese term means “purge through cleansing”). It is not known exactly how many people died; the official estimates given by the Japanese is 5,000 but the actual number is believed to be 8−10 times higher ↩