The A(YE), B(KE) and C(TE) of Expressways

Lim Tin Seng charts the history of Singapore’s expressways, from the oldest Pan-Island Expressway, built in the 1960s to the newest Marina Coastal Expressway.

AYE, BKE, CTE and ECP… the list goes on. These are not some random letters haphazardly thrown together but acronyms of Singapore’s expressways. Since making their appearance in the late 1960s, expressways have helped to ease congestion on arterial roads and ensure the smooth flow of traffic around the island.

The Early Roads

Expressways are dedicated roads that enable motorists to travel uninterrupted at high speeds from one place to another. Also referred to as highways, motorways, freeways or interstates – depending on which country you live – these are usually dual carriageways with multiple lanes in each direction. The world’s first expressway, Bronx River Parkway in New York, was built in 1908. By the 1930s, expressways were found in Europe when the initial phases of the Autobahn (Germany) and Autostrade (Italy) were completed.1

For most part of the 19th century, Singapore was served primarily by roads made of laterite, a reddish soil with a high iron oxide content.2 Trams, bullock carts and horse-drawn carriages traversed the streets, kicking up clouds of red dust as they transported goods and people around town and to other parts of the island.

Some of the frequently used roads at the time included Bukit Timah Road and Orchard Road which linked the fledgling town of Singapore to plantations in the north, Serangoon Road and Geylang Road to plantations in the east, and Tanjong Pagar Road and New Bridge Road to the port in the west. Over time, the expansion of the town followed the grid pattern of these main thoroughfares.3

As motor vehicles became prevalent in the early 20th century, laterite roads were replaced with asphalt-surfaced metalled roads. Paved with hand-packed granite, limestone and bituminous materials, these roads bore the weight of motorised vehicles and facilitated a much faster and smoother travel experience.4

Although metalled roads did not reach rural areas until the 1960s, the ease of motorised travel encouraged people to move to the suburbs, which in turn spurred the expansion of the island’s road network. By the end of the 1930s, major roads such as Upper Serangoon Road, Punggol Road, Changi Road, Jurong Road, Sembawang Road and Woodlands Road appeared on maps connecting the town centre to all corners of the island.5

Unfortunately, motor vehicles soon became a double-edged sword: in a matter of 10 years, from 1915 to 1925, the number of private registered motor vehicles on the island rose from 842 to 4,456. By 1937, the number had ballooned to 9,382, adding to traffic congestion in the town centre along with rickshaws, bicycles, trishaws and bullock carts.6

As traffic rules, which were first introduced in 1911, were inadequate, travelling on congested roads in the town centre became increasingly hazardous. It was common to see drivers – liberated by the lack of road signs and markings – weaving dangerously in and out of heavy traffic with nary a thought to the safety of other road users. The most vulnerable were rickshaw pullers and their passengers as well as pedestrians forced to walk on the streets because of the clutter blocking the “five-foot ways” (as pavements were called back then).7

The government tried to bring some order by launching the island’s first public road safety programme in 1947, and installing the first automatic traffic signals at the junction of Serangoon and Bukit Timah roads a year later. In 1950, a 30-mile-per-hour speed limit was imposed on all roads, and in 1952, the first zebra crossings were introduced in Collyer Quay.8

These improvements, however, were insufficient to improve traffic conditions, especially when the number of motor vehicles continued to grow, reaching nearly 58,000 in 1955.9 It was clear that a more concerted approach was needed. The opportunity came in 1951 when the Singapore Improvement Trust was asked to prepare a master plan to guide the physical development of the island.

Road Hierarchy

The master plan – completed in 1955 and implemented in 1958 – introduced a five-level road hierarchy to differentiate the island’s roads by function. At the highest level were arterial roads, such as Bukit Timah Road and Woodlands Road, that served the entire island. Major roads or radial routes, such as Geylang Road and Changi Road, linking the city centre to the suburbs came next. Next in the hierarchy were main thoroughfares or local roads, such as Cross Street and Market Street, which “bypassed” built-up areas. Then there were development roads that provided access to shops and buildings and, finally, minor roads.10

The master plan also introduced measures to improve traffic flow. These included segregating non-motorised vehicles and pedestrians from motorised vehicles, and increasing the width of a traffic lane to the optimum 10 ft. To relieve traffic congestion in the city centre, the master plan recommended the creation of a network of carparks with public transport connections along the fringes of the Central Business District to support a park and ride scheme.11 Under this scheme, motorists were encouraged to switch to public transport before entering the city.

The master plan also called for the establishment of three self-sufficient satellite towns in Woodlands, Yio Chu Kang and Bulim (now part of Jurong West) in an effort to reduce overcrowding in the city centre.

Despite these measures, the 1958 master plan was fundamentally flawed: the changes it proposed were based on the assumption that urban growth would be slow and steady, premised on a projected population growth of 2 million by 1972. Moreover, the plan did not formulate a long-term strategy for road planning other than identifying a few arterial roads to be straightened or widened and a few new ones to link the new housing estates in Queenstown and Toa Payoh to the city centre. The master plan also incorrectly surmised that existing roads would be sufficient to meet future traffic demands.12

The pace of urbanisation picked up in the early 1960s, and by the time Singapore achieved independence in 1965, its motor vehicle population had risen to nearly 200,000 and was growing at an alarming rate of about 80 new vehicles per day.13 This further worsened traffic congestion on the roads. Recognising the inadequacy of the 1958 master plan, the government commissioned the State and City Planning (SCP) study in 1967 to draft a new land use and transport plan, known later as the Concept Plan.

A Network of Expressways

The Concept Plan was conceived by the SCP team comprising staff from the Planning Department, Urban Renewal Department, Housing and Development Board, and the Public Works Department. Unlike the 1958 master plan, this new plan took into account the fact that Singapore’s population was projected to reach 4 million by 1992.14

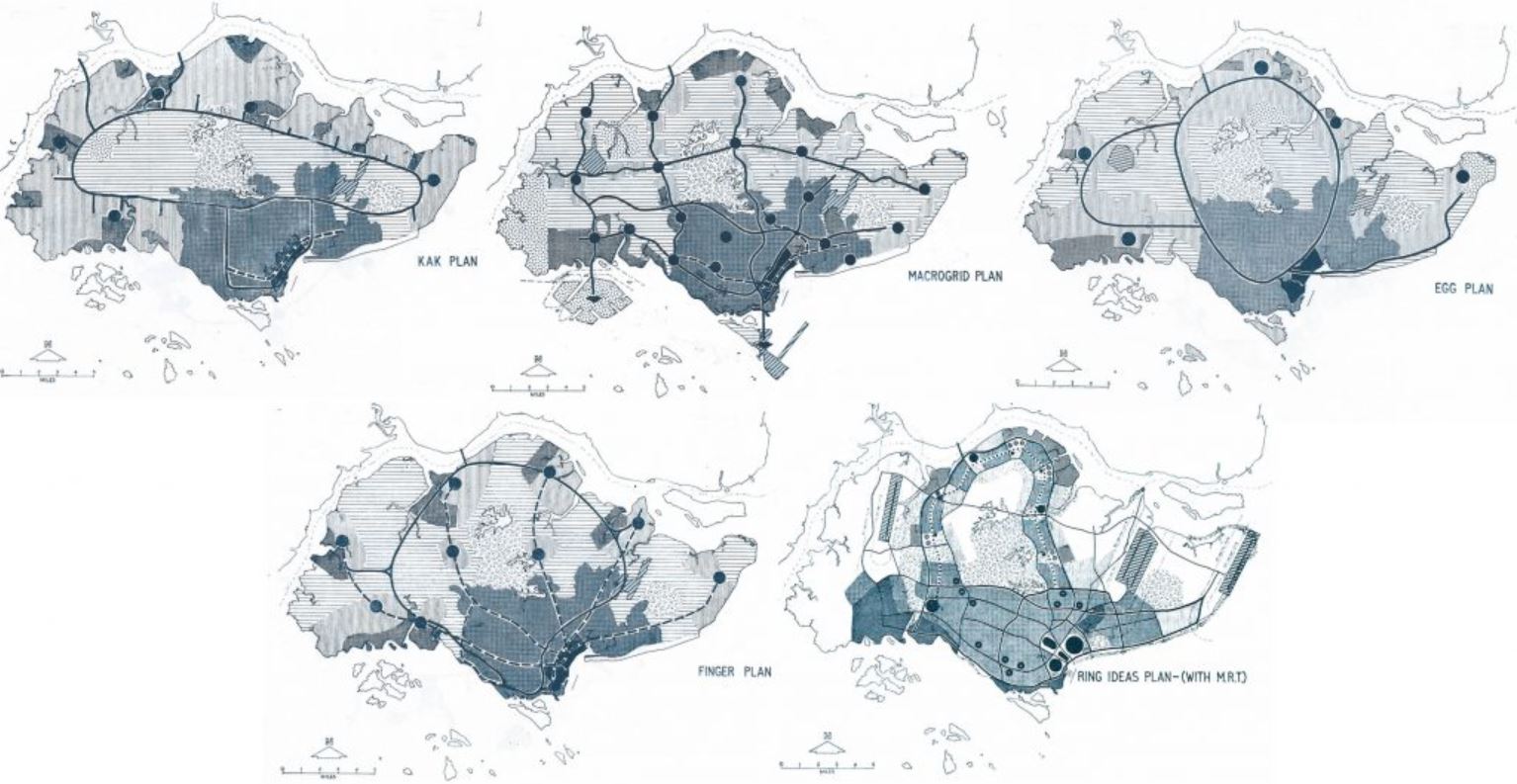

To develop the framework of the Concept Plan, the SCP team conducted a series of extensive surveys on land, building, population and traffic to identify how land could be optimised for growth and industrialisation.15 At the end of the intensive four-year study, the SCP team presented 13 draft concept plans for consideration.

Each of these plans offered a different interpretation of how the island’s land should be used, and how its transport network should be organised to connect people to housing, employment, services and recreation. For instance, the KAK Plan proposed connecting the different parts of Singapore by a large circular central expressway, while the Macrogrid Plan, as the name suggested, divided the island into a series of rectangular blocks using a web of expressways.16 The Finger Plan recommended that expressways radiate from the city centre like the five fingers of a hand, while the EGG Plan featured two interlinked egg-shaped expressways.

Eventually, the Ring Plan was adopted as Singapore’s first Concept Plan in 1971. It proposed moving the people away from the built-up and overcrowded city centre to high-density satellite towns encircling the central catchment area. The plan also recommended the establishment of a southern development belt spanning Changi in the east to Jurong in the west. Different pockets of activities would then be linked to one another and to the city centre by a network of interconnected expressways.17

The First Expressways: PIE and ECP

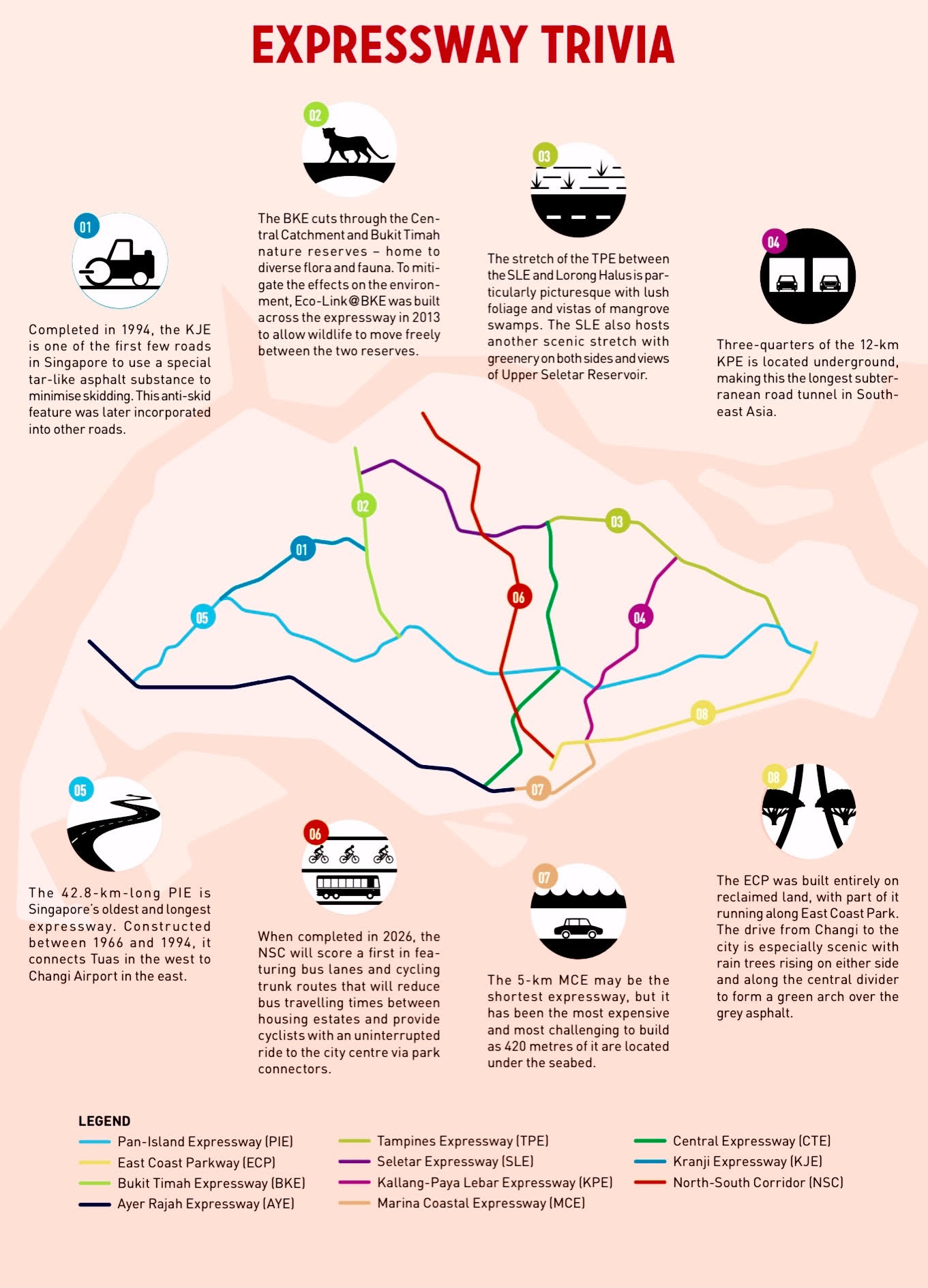

The location of the first expressways in Singapore was based largely on the proposals laid out in the 1971 Concept Plan. This included the island’s oldest and longest Pan-Island Expressway (PIE), a high-speed carriageway connecting industrial estates and housing estates along the southern development belt, including Jurong, Bukit Timah, Toa Payoh, Kallang, Eunos, Bedok and Tampines as well as Changi Airport.18

The 42.8-km PIE was initially conceived as a 35-km-long dual three-lane carriageway, with a central divider and hard shoulder. The 35-km stretch was constructed between 1966 and 1981 and involved four phases: Phase I between Jalan Eunos and Thomson Road, Phase II between Thomson Road and Jalan Anak Bukit, Phase III between Jalan Eunos and Changi Airport, and Phase IV between Jalan Anak Bukit and Jalan Boon Lay.19 In 1992, a new section at the western end was added to link the PIE to Kranji Expressway (KJE).20

During the construction of PIE, roads such as Jalan Toa Payoh, Jalan Kolam Ayer and Paya Lebar Way were widened, while flyovers such as Aljunied Road Flyover and Bedok North Avenue 3 Flyover were built to obviate the need for traffic light junctions.21 Grade-separated interchanges, including Thomson Road Interchange, Toa Payoh South Interchange and Bedok Road North Interchange, were also constructed to improve traffic flow into and out of the PIE.22 In 1978, a trumpet-shaped interchange was added at the eastern end of the PIE to connect it to the island’s second expressway – the East Coast Parkway (ECP).23

The 19-km ECP, built entirely on reclaimed land, links Changi Airport and major housing estates along the south-eastern coastline of Singapore to industrial sites and the CBD. Some of the estates that the ECP serves include Bedok, Siglap and Marine Parade. Construction took place over 10 years, between 1971 and 1981, in four phases. Phases 1 and 2 covered the stretch from Fort Road to Nallur Road, while Phases 3 and 4 comprised the 7-km portion from Nallur Road to Changi Road and the scenic 5.4-km section from Tanjong Rhu to Keppel Road respectively.24

One prominent feature of the ECP is the 185-hectare East Coast Park that runs alongside it. The park stretches over 15 km with access to a beach and amenities such as barbecue pits, cycling and jogging tracks, fishing spots, bicycle and skate rentals, food and beverage outlets, and chalets.25 A second feature of the ECP is the iconic 1.8-km Benjamin Sheares Bridge that links the expressway to the CBD and offers panoramic views of the city skyline. Named in memory of Singapore’s second president, the bridge spans Kallang Basin and Maria Bay and was the longest elevated viaduct on the island at the time.26

EXPRESSWAY GARDENS

Unlike the endless grey expanses of asphalt found in most countries, many of Singapore’s expressways are lined with trees providing shade and central dividers blooming with flowering shrubs. This is not an act of Mother Nature: when the PIE and ECP were constructed, specific instructions were given to beautify these expressways. On the drive from Changi Airport towards the city, tourists are usually struck by the image of Singapore as a beautiful garden city in the tropics.

The Era of Expressways: BKE, AYE, CTE, KJE, TPE and SLE

Another six expressways were built between the 1980s and 90s, touted as the “Era of Expressways”. During this period, the Public Works Department also carried out a series of improvements, such as the widening and re-alignment of existing expressways and roads. Underground roads, tunnels, viaducts, semi-expressways, flyovers and interchanges were also constructed to improve connectivity.27

The first expressway built during this period is Bukit Timah Expressway (BKE). Completed in 1986, the BKE begins at the Bukit Timah portion of the PIE and continues north towards Woodlands Checkpoint. It is a six-lane 11-km dual carriageway that serves housing estates in Woodlands, Bukit Panjang and Bukit Timah.

Hot on the heels of the BKE was Ayer Rajah Expressway (AYE), built in 1988. The 26.5-km AYE spans the south-western coast of Singapore, stretching from the western end of the Marina Coastal Expressway (MCE) to Tuas in the west. The expressway also passes Ayer Rajah industrial estate, which it is named after, as well as housing estates in Clementi, West Coast and Bukit Merah. The AYE is connected to Tuas Second Link, which was completed in 1995 and provides an alternative route to Johor in Malaysia.

The Central Expressway (CTE) was constructed one year later in 1989 to serve residents and industrial estates in Toa Payoh, Bishan and Ang Mo Kio. At 15.5 km long, this is currently the only expressway that connects the northern parts of the island directly to the city. Construction of the CTE was conducted in phases, and comprises segments from Seletar to Bukit Timah Road, Chin Swee Road to the AYE in Radin Mas, and the two tunnels (Chin Swee Tunnel and Kampong Java Tunnel) that run along the Singapore River, Fort Canning and Orchard areas.

The 1990s saw three expressways built: Kranji Expressway (KJE) in 1994, Tampines Expressway (TPE) in 1996 and Seletar Expressway (SLE) in 1998. The KJE is located in the northwestern part of the island. At 8.4 km, the expressway passes through Kranji industrial estate as well as housing estates in Bukit Panjang, Choa Chu Kang, Bukit Batok and Jurong. It also connects to the BKE at Gali Batu Flyover, and the PIE at Tengah Flyover.

The TPE in the northeastern part of Singapore serves the housing estates of Tampines, Pasir Ris, Lorong Halus, Punggol, Sengkang and Seletar. The 14.4-km expressway merges with the PIE near Changi Airport in the east. It also connects with the CTE and SLE in the northern part of the island. The stretch of the expressway between SLE and Lorong Halus is a particularly scenic drive with lush greenery and views of mangrove swamps and farmland.28

At almost 11 km long, the SLE, also in the northeastern part of the island, connects with the BKE at Woodlands South Flyover and terminates at the CTE-TPE-SLE interchange near Yio Chu Kang, providing greater connectivity to the residents of Woodlands, Yishun and Yio Chu Kang. The stretch of the SLE near the Upper Seletar Reservoir is a particularly scenic drive with lush greenery on either side.

As these expressways were being constructed, supporting arterial roads were widened to increase their capacity. Roads in the city centre were also improved, albeit on a limited scale, due to the heavily built-up nature of the area. Some of the improvements included converting roads prone to congestion into one-way streets, and removing street-level parking and itinerant hawkers to improve traffic flow.

In the years to come, a variety of other measures – many of them taking advantage of technology – were introduced to reduce traffic congestion. These included computerised traffic light management and measures to reduce the number of cars on the road, such as raising import duties and taxes, the introduction of the Vehicle Quota System to control the car population through Certificates of Entitlement (COE) that could be purchased via an open bidding process, and eventually, the Electronic Road Pricing System which charged motorists for usage of busy roads during peak hours.29

To encourage commuters to switch from cars to public transportation, the network of bus services was extended and improved. The game changer in public transportation, however, was the introduction of the island-wide Mass Rapid Transit (MRT) network in 1988. From the first 6km of the North-South line that opened in November 1987, the network has expanded to include four other lines – East-West, North-East, Circle and Downtown – with a sixth line in the making, the Thomson-East Coast line.

ECO-LINK @ BKE

Eco-Link@BKE is a 62-metre-long wildlife crossing spanning the Bukit Timah Expressway (BKE). Located between the Pan-Island Expressway and Dairy Farm exits, the ecological bridge – the first of its kind in Southeast Asia – reconnects Bukit Timah Nature Reserve and Central Catchment Nature Reserve that were split up when the BKE cut through the forest in 1986.

The eco-link, which opened in 2013, was constructed to provide a safe passage for native animal species, such as flying squirrels, monitor lizards, palm civets, pangolins, porcupines, birds, insects and snakes, between one reserve and the other. The ability to travel between the nature reserves is important as it allows the animals to expand their habitat, increase their forage range and enlarge their genetic pool, ultimately increasing their chances of survival.

To stimulate a natural environment, native trees and shrubs such as Oil Fruit Tree, Singapore Kopsia and Seashore Mangosteen were planted along the length of the bridge. The vegetation along the edges of the link acts as a buffer against traffic noise and pollution. To keep a record of animals using the bridge, cameras with motion sensors have been installed at strategic points along the link to monitor animal movement between the nature reserves.

Public guided walks organised by the National Parks Board between late 2015 and early 2016 have been suspended so as not to disturb the animals using the link.

Next-Generation Expressways: KPE and MCE

Despite the emphasis on public transport, plans were afoot to further improve the existing network of roads and expressways.30

Completed in 2008, the 12-km Kallang-Paya Lebar Expressway (KPE) was aimed at improving connectivity in the north-eastern corridor as well as cut travel time from the city centre to the newer housing estates of Sengkang and Punggol.31 The expressway also relieves pressure on the CTE, and is connected to the ECP, TPE and PIE.32 With three-quarters of the KPE located underground, it is the longest subterranean road tunnel in Southeast Asia.

The 5-km Marina Coastal Expressway (MCE) was completed at the end of 2013. It has a 3.6-km underground tunnel, with a 420-metre stretch of it located under the seabed, making this expressway the most expensive – and the most challenging to build – to date.33

The MCE connects the eastern and western parts of Singapore, and provides a high-speed link to the New Downtown area in Marina Bay. With the opening of the MCE, the section of the ECP between Central Boulevard and Benjamin Sheares Bridge was downgraded to an arterial road called Sheares Avenue, while the stretch between Central Boulevard and the AYE was demolished. This freed up prime land for the development of new projects in the Marina Bay area.34

The Future: NSC

In 2008, the government announced plans for the construction of Singapore’s 11th expressway, the 21.5-km North-South Corridor (NSC). When completed in 2026, the NSC will connect the city centre with towns along the north-south corridor. These include Woodlands, Sembawang, Yishun, Ang Mo Kio, Bishan and Toa Payoh. The NSC will also intersect and link up with existing expressways such as the SLE, PIE and ECP as part of the plan to improve the overall connectivity of the existing road network.35

The opening of the NSC in 2026 will usher in a new era of transport in Singapore. Expressways will no longer be seen as high-speed carriageways solely for motor vehicles; instead, they will be designed to complement public transport and even cater to non-motorised users. In anticipation of population growth and demographic changes in the next two decades, the government will have to think of innovative ways to improve road connectivity and deliver a world-class transport system in line with its vision to remake Singapore.

A unique feature of the NSC will be its dedicated bus lanes and cycling trunk routes. The bus lanes will help to reduce bus travelling times between housing estates along the new expressway and the city centre, while the cycling lanes will link up with the Park Connector Networks to provide cyclists with a direct route to the city centre. Both the bus and cycling lanes will support the government’s vision of transforming Singapore into a “car-lite” society where cycling and public transport would be the preferred mode of transport.36

Lim Tin Seng is a Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. He is the co-editor of Roots: Tracing Family Histories – A Resource Guide (2013); Harmony and Development: ASEAN-China Relations (2009) and China’s New Social Policy: Initiatives for a Harmonious Society (2010). He is also a regular contributor to BiblioAsia.

Lim Tin Seng is a Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. He is the co-editor of Roots: Tracing Family Histories – A Resource Guide (2013); Harmony and Development: ASEAN-China Relations (2009) and China’s New Social Policy: Initiatives for a Harmonious Society (2010). He is also a regular contributor to BiblioAsia.

NOTES

-

Lay, M.G. (2009). Handbook of road technology (p. 22). London: CRC Press. Retrieved from Google Books. ↩

-

Soh, E.K. (1983). A history of land transport in Singapore, 1819–1942 (p. 19). Singapore: National University of Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 388.4095957 SOH); Goh, C.B. (2013). Technology and entrepot colonialism in Singapore, 1819–1940 (pp. 102–103). Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. (Call no.: RSING 338.064095957 GOH) ↩

-

Thomson, J.T. (1846). Plan of Singapore Town and adjoining districts [Cartographic material]. London: J.M. Richardson. (Call no.: RRARE 912.5957 THO-[KSC]); Dale, O.J. (1999). Urban planning in Singapore: The transformation of a city (p. 17). Shah Alam: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 307.1216 DAL) ↩

-

Survey Department, Singapore. (1940). Singapore island [General map]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Trimmer, G.W.A. (1938). Report on the present traffic conditions in the Town of Singapore (pp. 6, 34). Singapore: Govt. Print. Off. (Microfilm no.: NL 7547) ↩

-

Sharp, I. (2005). The journey: Singapore’s land transport story (p. 74). Singapore: SNP Editions. (Call no.: RSING 388.4095957 SHA); Warren, J.F. (2003). Rickshaw coolie: A people’s history of Singapore, 1880–1940 (pp. 288–289). Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING 388.341 WAR) ↩

-

Fwa, T.F. (Ed.). (2016). 50 years of transportation in Singapore: Achievements and challenges (p. 207). Singapore: World Scientific. (Call no.: RSING 388.095957 FIF); Safety first at Collyer Quay. (1952, January 25). The Straits Times, p. 9; Speed limit for rural areas. (1950, January 5). The Singapore Free Press, p. 6; Governor heralds road campaign. (1947, May 12). The Straits Times, p. 1; 2 zebras go, one to come. (1953, June 12). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore. Registry of Vehicles. (1960). Annual report for the year 1960 (p. 1). Singapore: Govt. Print. Off. (Call no.: RCLOS 388.31 SIN-[AR]) ↩

-

Fwa, 2016, p. 204; Colony of Singapore. (1955). Master plan: Reports of study groups and working parties (p. 101). Singapore: F.S. Horslin. (Call no.: RCLOS 711.4095957 SIN) ↩

-

Colony of Singapore, 1955, pp. 54–55, 101. ↩

-

Colony of Singapore, 1955, pp. 52, 54. ↩

-

Singapore has 197,945 motor vehicles. (1966, January 22). The Straits Times, p. 14. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Fwa, 2016, p. 17; Urban Redevelopment Authority. (2014). Concept Plan 1971. Retrieved from Urban Redevelopment Authority website; Campbell, W. (1970, March 23). New impetus as ring plan gets go-ahead. The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Fwa, 2016, p. 130; Major survey of land and buildings. (1967, August 18). The Straits Times, p. 8; ‘Unique nation state’ plan. (1967, September 20). The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore. Planning Department. (1969). Annual report for the year 1968 & 1969 (pp. 4–18). Singapore: Planning Department. (Call no.: RCLOS 711.4095957 SPDAR) ↩

-

The Straits Times, 23 Mar 1970, p. 8; Campbell, B. (1970, April 8). What the Ring Concept Plan looks like. The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Land Transport Authority. (2013, August 17). Pan Island Expressway. Retrieved from Land Transport Authority website. ↩

-

Land Transport Authority, 17 Aug 2013; Public Works Department. (1967). Annual report for the year 1967 (p. 8). Singapore: Govt. Print. Off. (Call no.: RCLOS 354.59570086 SIN); Ministry of Culture. (1981, January 10). Speech by Mr Teh Cheang Wan, Minister for National Development, at the official opening of the Pan-Island Expressway between Jalan Eunos and East Coast Parkway, 10 January 1981 at 11 am [Press release]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website; Ministry of Culture. (1989). Singapore Yearbook 1989 (p. 145). Singapore: Govt. Print. Off. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 SIN). ↩

-

PIE will reach Tuas by ’94. (1992, January 8). The Straits Times, p. 3; PIE extension to open tomorrow. (1993, December 3). The Straits Times, p. 33. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Land Transport Authority, 17 Aug 2013; Public Works Department, 1967, p. 8. ↩

-

Ensuring nonstop traffic flow. (1980, December 18). The Straits Times, p. 20. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Interchanges for eastern part of PIE to cost $34m. (1978, January 11). The Straits Times, p. 15. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Campbell, W. (1971, August 8). Where 100,000 will live and play on reclaimed East Coast. The Straits Times, p. 6; Scenic highway contract goes to Japanese firm. (1976, September 9). The Straits Times, p. 17; Pointers give drivers a pleasant trip. (1981, April 18). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

National Parks Board. (2018, March 19). East Coast Park. Retrieved from National Parks Board website. ↩

-

Last part of East Coast Parkway to open. (1981, September 25). The Straits Times, p. 11; New expressway will serve long-term needs. (1981, April 18). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Sharp, 2005, p. 69; Dhaliwal, R. (1995, March 5). $1.9 b for roads over next 5 years. The Straits Times, p. 3; Lee, H.S. (1986, March 21). Record budget for roads. The Business Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The TPE runs through it. (1996, September 6). The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

A smooth glide to Jurong and Tuas. (1990, April 7). The New Paper, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Fwa, 2016, pp. 203–204. ↩

-

Singapore. Land Transport Authority. (1996). A world class land transport system: White paper (p. 20). Singapore: Land Transport Authority. (Call no.: RSING 388.4095957 SIN) ↩

-

Cheong, C. (2008). Building Singapore’s longest road tunnel: The KPE story (p. 19). Singapore: SNP Editions. (Call no.: RSING 624.193095957 CHE); Land Transport Authority. (2008). Transcending travel: A macro view: Annual report 2007/2008 (p. 30). Retrieved from Land Transport Authority website. ↩

-

Ng, D. (2008, September 20). KPE by numbers. The New Paper, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Ministry of Transport. (2013, December 28). MCE opening ceremony. Retrieved from Ministry of Transport website. ↩

-

Land Transport Authority. (2015, December 14). Marina Coastal Expressway: Features. Retrieved from Land Transport Authority website. ↩

-

Two more expressways in 2013, 2020, says PM Lee. (2008, September 20). Today, p. 16. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Land Transport Authority. (2017, June 6). North-South Corridor. Retrieved from Land Transport Authority website. ↩

-

Land Transport Authority, 6 Jun 2017; Land Transport Authority. (2016, April 28). LTA to call for tenders for North-South Corridor [Press release]. Retrieved from Land Transport Authority website; Becoming a ‘car-lite’ society. (2015, October 6). Today, p. 20. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩