Blazing a Trail: The Fight for Women’s Rights in Singapore

The Singapore Council of Women was the city’s first female civil rights group that took bold steps to champion laws affecting women. Phyllis Chew documents its hard-won victories.

“Forget for a time the rights and privileges which a dying custom and a faulty judgment bestows upon a selfish husband, and learn to think in terms of your duties as fathers. The destiny of millions of Chinese girls is in your hands. Deal with them as you would like your daughters to be dealt with.”1

Singapore Council of Women, 23 August 1954

After the Japanese Occupation ended in 1945, Singapore women – emboldened by a political awareness brought about by the events of World War II – emerged with a greater confidence in their abilities. They had witnessed the humiliating defeat of British forces by Japanese military might, and with it a shattering of the myth of white colonialist supremacy.

Taking inspiration from women such as Elizabeth Choy, the war heroine who was incarcerated and tortured by the Japanese military police, gender-related inhibitions were slowly cast away. Women began contributing to the war rehabilitation effort – for the first time two women were elected to the Municipal Commission2 – and started reaching out to less fortunate segments of society.

Emerging from the confines of their homes, women volunteered for jury services and several took office as Justices of Peace. They volunteered at feeding centres set up by the colonial government for thousands of impoverished children who were denied food and basic nutrition. Others banded together to establish the first family planning association in Singapore, convinced that families should have no more children than they could feed, clothe and educate.

Women recreated an identity for themselves by setting up alumni associations (such as Nanyang Girls’ Alumni), recreational groups (Girls’ Sports Club) race-based groups (Kamala Club) religious groups (Malay Women’s Welfare Association), housewives’ groups (Inner Wheel of the Rotary Club), professional groups (Singapore Nurses’ Association), national groups (Indonesian Ladies Club) and mutual help groups (Cantonese Women’s Mutual Help Association).

One association, however, stood out amidst the post-war euphoria – the Singapore Council of Women (SCW). This was a group energised by its vision of uniting Singapore’s diverse women’s groups across race, language, nationality and religion in its fight for female enfranchisement. Looking back at the history of women’s rights movement in Singapore, it would not be an overstatement to claim the SCW marked the awakening of Singapore women to a new and heightened consciousness of what they could achieve.

By defining clear goals, organising working groups, enlisting public support, and engaging the media, government and the international community, the SCW showed how Singaporean women, hitherto overshadowed and relegated to the fringes of society, would lead the way in changing their status quo.

Origins of the Singapore Council of Women

The seeds of the SCW were sown on 12 November 1951 when a small group of women under the leadership of Shirin Fozdar (see text box below) called a public meeting to discuss the formation of an organisation that would champion women’s rights in Singapore. Thirty prominent women in the community met, including Elizabeth Choy, Vilasini Menon, and Municipal Commissioners Mrs Robert Eu (nee Phyllis Chia) and Amy Laycock (see Note 2).

The women agreed that despite the fine work done by the Young Women’s Christian Association, the Social Welfare Department and the Malay Women’s Welfare Association, their “admirable work could not ameliorate the legal disabilities under which women have been suffering and which were the root causes of many of the social evils”.3

Accordingly, Fozdar called for the setting up of a new organisation that would unite the women of Singapore and would not “overlap [with] the work and activities of the existing social welfare organisations, but go to the root causes of all the social evils that exist and handicap the progress of women towards their emancipation and their enjoyment of equal rights…”.4

Taking advantage of the politically conducive climate, the SCW was inaugurated on 4 April 1952, barely five months after that first meeting mooted by Fozdar. The first executive committee (with Fozdar as Secretary-General and Choy as President) comprised mainly members drawn from the main women’s groups of the period, including the YWCA. Altogether there were seven Chinese, four Indians, two Malays, one Indonesian and one Briton – a composition that would not change much over the next 10 years. This racial mix in turn reflected the composition of the rank-and-file SCW membership; the majority were Chinese, followed by Malays, Indians, Eurasians and Europeans.

An International Sisterhood

Influenced by two of its members – Winnifred Holmes, the overseas representative of the Women’s Council of the United Kingdom in Singapore and V.M. West, a former member of Britain’s National Council of Women – one of the first things that the SCW did was to affiliate itself with leading overseas women’s rights groups, such as the International Council of Women (ICW), the National Council of Women in Great Britain, the National Council for Civil Liberties in London, and the British Commonwealth League.5

Viewing itself as part of a network of a worldwide confederation of women, the SCW kept abreast with world affairs and lobbied for women’s rights through letter and telegram lobbies. When British women petitioned the House of Commons on 9 March 1954 to demand for “equal pay for equal work”, the SCW sent a telegram of support. When the United Nations Economic and Social Council registered the Convention on the Status of Women on 7 July 1954, the SCW alerted the local press.6 When Egyptian feminist Doria Shafik went on a hunger strike in March 1954 to seek voting rights for the women of her country, the SCW sent a telegram to General Muhammed Neguib of Egypt asking him to consider her demands.7

Closer to home, when Perwari, the Indonesian Women’s Association, marched to Indonesian Prime Minister Ali Sastroamidjojo’s office demanding the abolition of polygamy and child marriages in December 1953, the SCW extended its support.8 When Governor of Singapore Robert Black was transferred to Hong Kong in 1957, the SCW petitioned him to assist the Hong Kong Council of Women in its efforts to change marriage laws in the British colony.9

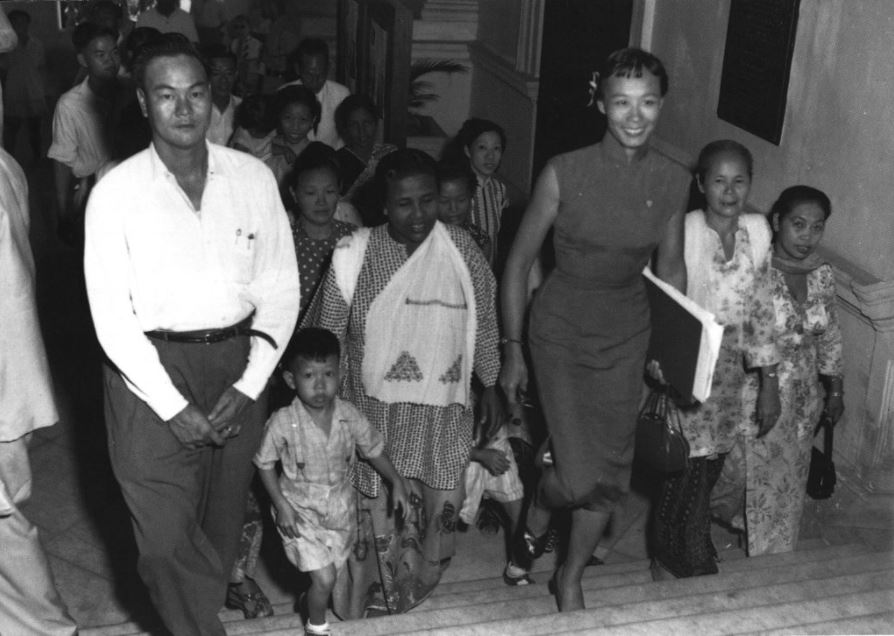

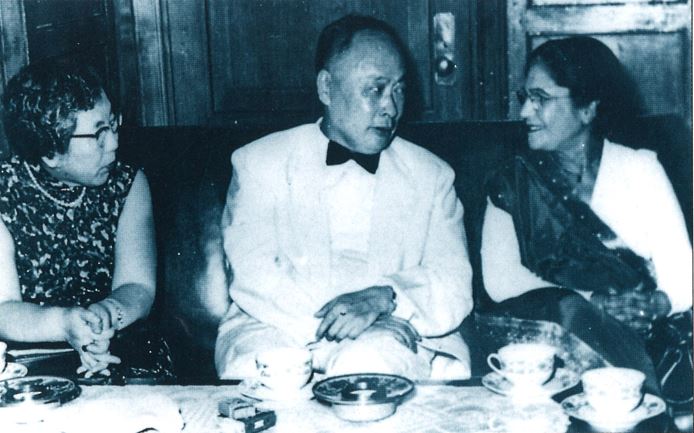

Both Fozdar and the SCW’s second president Mrs George Lee (nee Tan Cheng Hsiang) liaised with women’s groups in Hong Kong, Vietnam, Cambodia, China and Britain and undertook lecture tours.10 At the 1958 Afro-Asian Conference in Colombo, Fozdar’s criticism of Singapore as an important stop in the trade of Asian women triggered press publicity and caused an uproar with government officials, including Singapore’s Chief Minister Lim Yew Hock.11 The SCW had been increasingly concerned about prostitution in Singapore as well as the rising number of girls and women from Hong Kong and China sold to brothel owners against their will.12

In the Public Eye

Throughout the 1950s, the SCW raised its public profile in Singapore by giving public talks to make its agenda known.13 But it wasn’t all talk and no action. The group developed its own distinct brand of community service. Instead of merely raising funds and working with existing welfare organisations, the SCW pioneered several new initiatives that it ran itself.

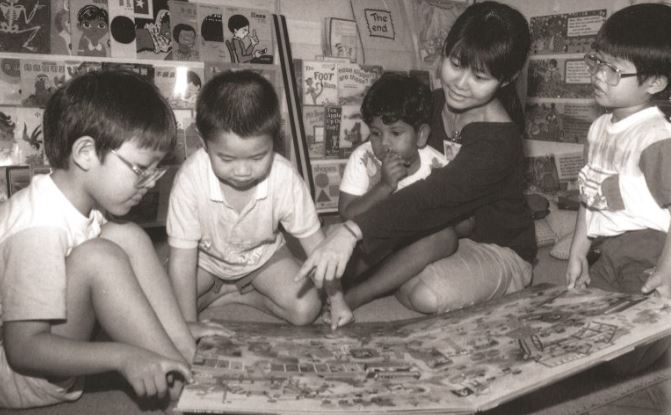

In February 1953, the SCW set up the first girls club in Singapore. Money was raised and a suitable site at Joo Chiat Welfare Centre was found. Equipment such as typewriters and sewing machines were donated, and SCW members recruited to teach English, cooking, sewing and self-defence. The club proved so popular that 200 girls registered on the first day, forcing the SCW to transfer some classes to Tanjong Katong Girls’ School.14

Another task the SCW pioneered was the setting up of crèches in factories in 1952. Noticing that large numbers of working women were finding it difficult to raise their children with full-time jobs, they appealed to factories that employed more than 100 women – such as Lee Rubber Co Ltd., Malayan Breweries and the Dunlop Rubber Purchasing Co. Ltd. – to consider setting up crèches within their factory premises.15 SCW members offered advice on how to run these crèches economically “so that children will not be left unattended… while the mother is at work”. Unfortunately, while some factories promised to look into the matter, most were reluctant to take up SCW’s offer.

The main focus of the SCW, however, was to provide counselling to the many hapless women who had been deserted or divorced by their husbands. SCW members spent much time liaising with the Department of Social Welfare on marriage counselling, and pressured the Department of Immigration to curb the importation of women from Hong Kong, China and Japan who came to Singapore to become secondary wives. With regard to the vice trade, the SCW proposed establishing a centre where women who wished to leave prostitution could be rehabilitated and taught useful skills to make a new living for themselves; this call, however, fell on deaf ears.16

Municipal Commissioner Mrs Robert Eu, who was a founding member of the SCW recalled: “Whenever, a mother came to see me in tears that her husband was taking another wife because she was three months pregnant, I had to tell lies to Immigration so as to prevent the man from importing another wife from Shanghai.” Lies were necessary because “if I told the truth, they would say I was interfering with Chinese customs, so I had to say he was importing a wife to be a prostitute”.17

The Fight Against Polygamy

In 1953, the SCW drafted an ordinance, the Prevention of Bigamous Marriages, which it distributed to members of the Legislative Assembly.18 The bill essentially called for the abolition of bigamous marriages.

This was a time when women were completely subject to customary and religious laws that allowed men to take more than one wife. Divorce laws were lax and women were greatly disadvantaged. While a man could divorce his wife on the slightest pretext, women could not do the same since the wife and children were often financially dependent on the husband as head of the household.

In addition, as most marriages were not properly registered, women were left with few rights for settling grievances in court and often had to resort to government or quasi-government agencies like the Social Welfare Department and the Chinese Consulate General for informal arbitration.

However, the bill was roundly criticised by conservative leaders from the Malay, Indian and Chinese communities, all of whom protested against it on the grounds of culture and customary laws.19 Undaunted, the SCW appealed to the colonial government, calling on the British authorities “to do for the women of Singapore what Lord Bentinck, your countryman, did for the women of India”.20

In 1954, a petition was sent to Stanley Awbery, a member of the House of Commons in England, decrying “the terrible insecurity of married life in this country” and the opposition the SCW faced in its attempts to institute reforms. The petition prompted Awbery to ask the Secretary of State for the Colonies in the House of Commons to report on the divorce rate in Singapore as well as “the steps which were being taken to tighten the marriage and divorce laws so as to give the women the same marital rights as are enjoyed by women in other parts of the British Commonwealth”.21

The colonial government was placed in a difficult situation. While concerned with the protection of women in the colony, they were unwilling to interfere in local customs and careful with enacting legislation that would arouse religious controversies. The British authorities advised the SCW to first change the opinions of the men sitting on the Muslim Advisory Board (MAB) with regard to the rampant practice of polygamy, the high divorce rate and the many instances of girls under 16 years of age who had been divorced multiple times in the community.

Following this advice, the SCW began to petition the MAB for reforms. Thus began in 1953 a series of correspondences between the SCW and the MAB, the local body responsible for advising the government on social, cultural, economic and religious matters pertaining to Muslims.22

In 1953, SCW’s Muslim sub-committee members, many of whom had joined anonymously “for fear of being divorced” by their husbands, produced a handbill that was distributed to various kampongs. Quoting from the Quran, the handbill argued that monogamy, rather than polygamy, was the natural state of affairs:

“And if you fear that you cannot act equitably towards orphans, then marry such women as seem good to you, two and three and four; but if you fear that you will not do justice [between them] then [marry] only one or what your right hand possesses [i.e. females taken as prisoners of war]; this is more proper that you may not deviate from the right course.”23

However, the police quickly put a stop to the distribution of these handbills for fear of serious repercussions (Shirin Fodzar had already been threatened with murder on two occasions).

In 1955, the SCW wrote to General (and to be president) Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt, then the dominant force in Arab politics, imploring him to rescue Muslim women all over the world and to legislate for monogamous marriage, so that other Muslim countries could follow in Egypt’s footsteps.24

Aware that marriage laws in the Federation of Malaya were more flexible and that Malay men wishing to avoid Singapore’s stricter laws could make use of the loophole and get married in Johor, the SCW began to include the Federation in their agenda. In November 1955, a petition was also sent to all the Sultans in the Malay states.

A series of talks was undertaken by SCW committee members between 1955 and 1957 in the town halls of Kuala Lumpur, Penang, Ipoh, Taiping and Muar.25 Fozdar’s rallying cry that “shame and misery are forced on Muslim women in Malaya in the name of God and religion”26 at one of these talks won her many supporters as well as opponents.

Another reason the SCW took its fight across the border was because it was fired by its ambition to establish a Malayan Women’s Council (which would include Singapore in its make-up). Although The Malay Mail reported that Shirin Fozdar and the SCW had “a rapidly increasing following throughout Malaya and Singapore and not from the womenfolk only”,27 it criticised “her programme for a Malayan Women’s Council… as revolutionary in its way as that of the most extreme nationalists in Malaya”.28

Nevertheless, the seeds had been planted: a meeting of the UMNO Kaum Ibu (Women’s Section of the United Malay National Organisation) in 1958 moved a resolution that concrete steps should be taken to curb the high divorce rates and that divorced women should be given alimony.29 A National Council of Women’s Organisations (NCWO) in Malaya also took root in 1963 with the express aim of raising the status of women by fighting for, among other things, reforms in marriage and divorce laws.

These developments placed pressure on the conservative MAB in Singapore for reforms and to agree to most of SCW’s demands as stipulated in the Muslim Ordinance of 1957.

The Women’s Charter of 1961

Between 1955 and 1959, the SCW lobbied various political parties in Singapore to address the injustices faced by women, arguing that “the attainment of independence will remain an idle dream if the men in this country do not rise to generous heights to grant that independence to their own kith and kin – the women of the country”.30

While leaders of several political parties jostling for power – this was the tumultuous period before the British acceded to Singapore’s request for internal self-government in 1959 – were sympathetic to SCW’s cause, they felt that putting it down as party policy could cost them votes in future elections due to its controversial nature.31 However, the People’s Action Party (PAP), under pressure from members of its Women’s League – many of whom were young, Chinese educated and markedly socialist in their ideals – took the strongest stand on women’s rights.

Launched in 1956 under the leadership of Chan Choy Siong, a pioneer female politician, the PAP Women’s League adopted SCW’s 1952 slogan of “one man one wife”, as part of its anti-colonial manifesto.32 The first big event organised by the league was the celebration of International Women’s Day on 8 March 1956.

The rally was held at four places simultaneously and attended by more than 2,000 people, most of whom were trade unionists and Chinese school students.33 Women leaders from all walks of life were invited to celebrate the occasion. The SCW’s representative was Shirin Fozdar, who urged the frenzied crowd to support the abolition of polygamy. On the same day, a resolution was passed by the Women’s League in support of the principle of monogamy (and subsequently moved during the PAP’s annual general meeting in 1957).

Thus, the PAP became the only political party to campaign openly on the “one man one wife” slogan. The extent to which the adoption of women’s rights contributed to the PAP’s unexpected landslide victory in the 1959 general election that launched Singapore as a fully self-governing state should not be underestimated.34 Women came out in full force on polling day because voting was now compulsory. The party’s clear victory – it won 43 of the 51 seats contested – and its subsequent control of the Legislative Assembly meant that Singapore society was now prepared to accept the idea of civil rights for women. As a result, the long-drawn-out controversy over the issue of polygamy and child marriages finally came to an abrupt end.

It took two years before the Legislative Assembly passed the Women’s Charter Bill on 24 May 1961 – with the ordinance coming into force on 15 September 1961 – finally bringing to a climax SCW’s decade-long fight for women’s rights. The Charter provided that the only form of marriage permitted would be monogamous, whether the rites were civil, Christian or customary. Women could now sue their husbands for adultery and bigamy, and receive both a fair hearing and justice under the law. The Charter strengthened the law relating to the registration of marriages and divorce, and the maintenance of wives and children, and also contained provisions regarding offences committed against women and girls.

Although the Charter did not apply to Muslim women, its promulgation forced the Muslim community to look into ways of further improving the status of Muslim women through an amendment of the Muslim Ordinance of 1957. In 1960, the Muslim Syariah Court was empowered to order husbands to provide maintenance to their divorced wives until these women remarried or died. Getting divorced was no longer a simple process for Muslim men, and they were not allowed to take another wife if they were unable to show proof of their financial means. Although the SCW was unable to introduce monogamy in Muslim marriages, it was, nonetheless, able to limit the practice of polygamy.

The End of the Singapore Council of Women

Having achieved her mission, Shirin Fozdar left Singapore in 1961 to set up the Santhinam Girls’ school in Yasohorn, northeast Thailand, an impoverished area where rural girls would have opportunities to learn livelihood skills instead of resorting to prostitution.

Deprived of Fodzar’s vision and dynamism, the SCW languished in the 1960s under a new political climate that saw grassroots organisations, such as the People’s Association, taking over many civic activities that were once left to NGOs. Eventually, left without a purpose and mission, the SCW was deregistered in 1971.

The SCW’s legacy goes far beyond the successful lobbying that led to the Women’s Charter of 1961. It blazed an entirely new path for women after World War II, seeing women as being equal to men and lifting women’s groups in Singapore beyond fundraising, social networking and self-improvement courses.

Rather than accept that women could only play supporting roles to men in society, the SCW confronted the injustices faced by all women in Singapore. From the outset, the SCW was single-minded in the pursuit of its goals, vociferous in its demands, wide-ranging in its call for reforms benefiting women, and forward-looking in its agenda. In short, the SCW was responsible for the awakening of Singapore women to a new consciousness of themselves as humans with a purpose and a goal.

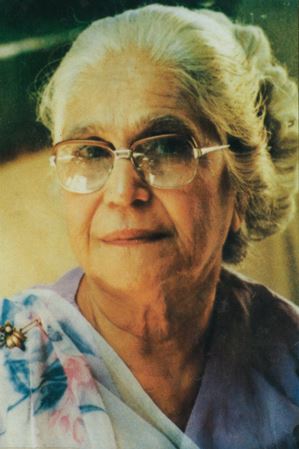

Shirin Fozdar was born in 1905 in Bombay (now Mumbai), India, to Persian parents. She studied at a Parsi school in Bombay and then at St Joseph’s Convent in Panchgani, Maharashtra. After graduating from Elphinstone College, she enrolled at the Royal Institute of Science (both in Mumbai) to study dentistry, where she met her husband, Khodadad Muncherjee Fozdar, a doctor. When the couple arrived in Singapore in 1950, polygamy was a common and accepted practice.

As Secretary-General of the Singapore Council of Women between 1952 and 1961, Fozdar was the “brains” and public face of the women’s rights group. Inspired by the Baha’i principle that men and women are equal in status, Fozdar had begun the fight for the emancipation of women in India when she was just a teenager.

Shirin Fozdar was the Secretary-General of the Singapore Council of Women between 1952 and 1961. Strongly believing that women are equal to men, she had begun the fight for the emancipation of women in India when she was just a teenager. Image reproduced from Ong, R. (2000). Shirin Fozdar: Asia’s Foremost Feminist (cover). Singapore: Rose Ong. (Call no.: RSING 297.93092 ONG).

Shirin Fozdar was the Secretary-General of the Singapore Council of Women between 1952 and 1961. Strongly believing that women are equal to men, she had begun the fight for the emancipation of women in India when she was just a teenager. Image reproduced from Ong, R. (2000). Shirin Fozdar: Asia’s Foremost Feminist (cover). Singapore: Rose Ong. (Call no.: RSING 297.93092 ONG).

Her involvement in the women’s movement in India culminated in her nomination in 1934 as the country’s representative at the All Asian Women’s Conference on women’s rights at the League of Nations in Geneva. In 1941, Fozdar delivered peace lectures to the riot-torn Indian city of Ahmedabad on the instructions of Mahatma Gandhi, leader of the Indian independence movement against British rule, who called her “his daughter”.

Fozdar passed away from cancer on 2 February 1992 in Singapore, leaving behind three sons and two daughters; her husband had died in 1958. Her personal collection comprising newspaper clippings, letters, correspondences, minutes of meetings, receipts and invoices are on loan to the National Library Board for digitisation by her son Jamshed. These are found in the library’s Jamshed & Parvati Fozdar Collection.

The SCW was a broad-based organisation with four main objectives:

–affiliation with other women’s organisations in Singapore;

–furthering the cultural, educational, economic, moral and social status of women in Singapore;

–ensuring through legislation, if necessary, justice to all women and to further their welfare as embodied in the Declaration of Human Rights Charter;

–facilitating and encouraging friendship, understanding and cooperation among women of all races, religions and nationalities in Singapore.

REFERENCE

The Constitution of the SCW, Registrar of Societies, 1952.

Dr Phyllis Ghim-Lian Chew is a professor at Nanyang Technological University. She has written many books, including Emergent Lingua Francas (Routledge, 2009) and A Sociolinguistic History of Early Identities in Singapore (Palgrave, 2010). She is past president of AWARE (Association of Women for Action and Research) and UWAS (University Women’s Association of Singapore).

Dr Phyllis Ghim-Lian Chew is a professor at Nanyang Technological University. She has written many books, including Emergent Lingua Francas (Routledge, 2009) and A Sociolinguistic History of Early Identities in Singapore (Palgrave, 2010). She is past president of AWARE (Association of Women for Action and Research) and UWAS (University Women’s Association of Singapore).

NOTES

-

SCW to Chinese Advisory Board, 23 August 1954; SCW to Secretary for Chinese Affairs, 11 November 1954. ↩

-

The first two women elected to the Municipal Commission were Mrs Robert Eu (nee Phyllis Chia) in 1949 and Miss Amy Laycock in 1950. The Municipal Commission was renamed the City Council in 1951 when Singapore acquired city status. ↩

-

Minutes of Protem Committee, 20 November 1951. ↩

-

Minutes of Protem Committee, 20 November 1951. ↩

-

SCW to President, International Council of Women 6 January 1959; YWCA to SCW 31 May 1954, Minutes of the SCW 9 September 1953. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press, 15 July 1954. ↩

-

SCW to General Neguib of Cairo, March 1954. ↩

-

SCW to Indonesian Women’s Association, Djarkarta, 26 December 1953. ↩

-

Minutes of the SCW, 30 July 1958. ↩

-

Annual report of the SCW, 1954 and 1960; The Sunday Times, 17 August 1958; The Singapore Free Press, 8 August 1959; The Straits Times, 10 August 1959; The Sunday Times, 6 September 1959, The Straits Times, 8 September 1959. ↩

-

The Sunday Times, 17 August 1958; Minutes of the SCW 1 June 1957, 18 November 1957 and 19 March 1958. ↩

-

SCW to Minister for Labour and Welfare, 16 September 1957; Minister for Labour and Welfare to SCW, 25 September 1957. See also Lai, A.E. (1986). Peasants, proletarians and prostitutes: A preliminary investigation into the work of Chinese women in colonial Malaya (pp. viii, 115). Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. (Call no.: RSING 331.409595104 LAI) ↩

-

The Straits Times, 29 April 1952; The Straits Times, 2 March 1952; The Straits Times, 6 August 1957; The Singapore Free Press, 30 August 1957; The Straits Times, 26 July 1958; The Singapore Free Press, 15 October 1959; The Sunday Times, 2 August 1959; see also Rev S.M. Thevathasan to SCW, 27 February 1952 and Methodist Fellowship Group to SCW, n.d. ↩

-

Muriel Blythe to the SCW, 17 February 1953; The Straits Times, 2 April 1953; The Singapore Free Press, 16 February 1953; The Straits Times, 20 February 1953; Minutes of the SCW, 19 September 1953, 20 October 1953 and 16 September 1957. ↩

-

Lee Seng Gee to SCW, 2 July 1952; Dunlop Rubber to SCW, 3 July 1952; Malayan Breweries to SCW, 14 July 1952. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press, 30 July 1958; Minutes of the SCW, 16 October 1957, 18 November 1957 and 3 January 1958. ↩

-

Interview with Mrs Robert Eu, 11 November 1992. ↩

-

See Appendix A in Chew, P.G.L. (1994, March). The Singapore Council of Women and the women’s movement. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 25 (1), 112–140, p. 139. ↩

-

Minutes of the SCW, 5 January 1954. ↩

-

SCW to the Governor-in-Council, 3 June 1957. ↩

-

House of Commons, Reply from Hopkinson to Awbery, 27 January 1954; Letter of Awberry to SCW, 21 January 1954. ↩

-

Minutes of the SCW, 6 August 1953; SCW to MAB, 14 December 1953 and 19 March 1954; MAB to SCW, 18 December 1953. ↩

-

Handbill distributed by the SCW, c. December 1953/January 1954. See also Minutes of SCW, 8 January 1954, 12 January 1954 and 9 February 1954. ↩

-

SCW to President Nasser of Egypt, 8 September 1955. ↩

-

Borneo Bulletin, 19 March 1954; The Malay Mail, 23 May 1955; The Straits Times, 20 April 1958; The Malay Mail, 25 July 1960. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 5 February 1958; The Weekender, 7 March 1958. ↩

-

The Malay Mail, 25 April 1958. ↩

-

The Malay Mail, 30 May 1955. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 7 June 1958. ↩

-

The Malay Mail, 9 July 1955; The Weekender, 4 November 1955. ↩

-

J.M. Jumabhoy to Shirin Fozdar. 26 April 1958; Chief Minister Lim Yew Hock to Shirin Fozdar, 22 March 1956; SCW to Chief Minister Lim Yew Hock, 3 February 1958; SCW to Chief Minister Lim Yew Hock, 6 July 1955; See also The Malay Mail, 9 July 1955. ↩

-

Interviews with Dr Toh Chin Chye, 27 January 1993; and S. Rajaratnam, 1 February 1993. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 9 March 1956. ↩

-

Interview with Ong Pang Boon, 27 January 1993. ↩