In Honour of War Heroes: The Legacy of Colin St Clair Oakes

Who was the architect behind Singapore’s Kranji War Cemetery and other similar memorials in South and Southeast Asia? Athanasios Tsakonas has the story.

On a bright and early Saturday morning on 2 March 1957, Governor of Singapore Robert Black presided over the unveiling of the Singapore Memorial at the Kranji War Cemetery. Under a sky filled with towering clouds, Black, a former prisoner-of-war interned in Changi during the Japanese Occupation (1942–45), was received by Air Marshal Sir Arthur Longmore, Vice-Chairman of the Imperial War Graves Commission (IWGC).

Some 3,000 guests, including dignitaries and representatives of the various Commonwealth governments, had gathered to bear witness to the culmination of an event that had commenced over a decade earlier in the aftermath of World War II.

Unveiling the Memorial

As the party comprising Black, selected guests and the presiding clergy was about to lay their wreaths at the base of the Cross of Sacrifice, a weeping, elderly Chinese woman dressed in a worn samfoo suddenly emerged from the crowd and stumbled up to the cross. Major-General J.F.D. Steedman, Director of Works at the IWGC, gently put his arm around her shoulders and led her away to a chair under the shade of a tree. Journalist Nan Hall reported in The Straits Times the following day that the woman had “sobbed loudly and rocked her head in her hands”.1

Following the unveiling and a short speech by Governor Black, the Last Post was played, hymns were sung, and blessings offered by clergy from the Hindu, Islam, Buddhist and Christian faiths. A flypast by jet fighters from the Royal Australian Air Force punctured the sky in a salute. The British national anthem, God Save the Queen, concluded the service prior to the laying of wreaths and inspection of the memorial by invited guests. The ceremony, steeped in the tradition of a protocol dating from the beginnings of the IWGC in 1917, would be over within a few hours.

After the ceremony, the sobbing woman identified herself as Madam Cheng Seang Ho (alias Cheong Sang Hoo), an 81-year-old wartime heroine whose husband’s name was one of those engraved on the very memorial being unveiled. Madam Cheng and her husband Sim Chin Foo (alias Chum Chan Foo) had joined a group of army and civilian fighters known as Dalforce during the Japanese Occupation.2 Her husband would subsequently be captured by the Kempeitai, the Japanese military police, and tortured to death.3

It was a poignant moment that captured the essence of the human sacrifice the memorial was erected to convey, not only for the servicemen who died in the war and whose names were inscribed on the stone panels, but also for those who would come to pay their respects and find some measure of solace.

The Legacy

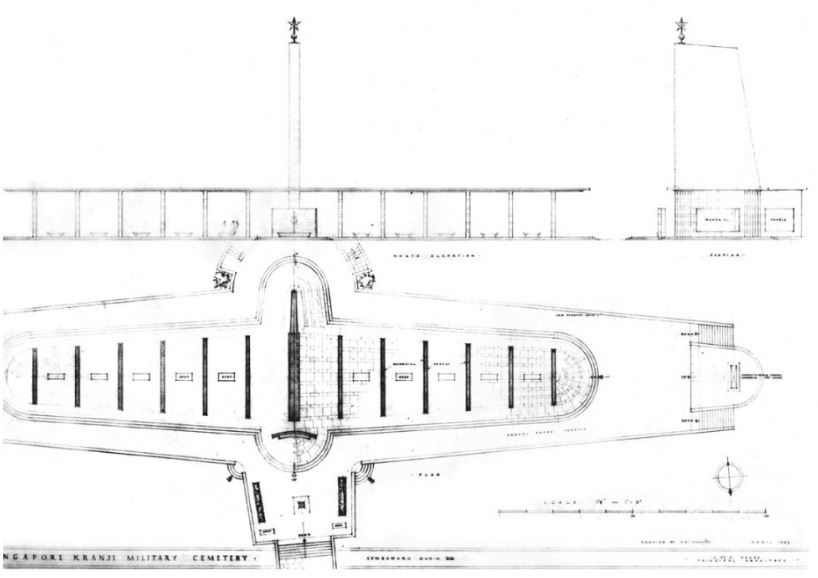

Designed by a relatively unknown young architect named Colin St Clair Oakes (see text box below), the Kranji War Cemetery resembles the design of many such war cemeteries he would design in South and Southeast Asia, influenced by his military service background and experience of having lived and worked in this part of the world.

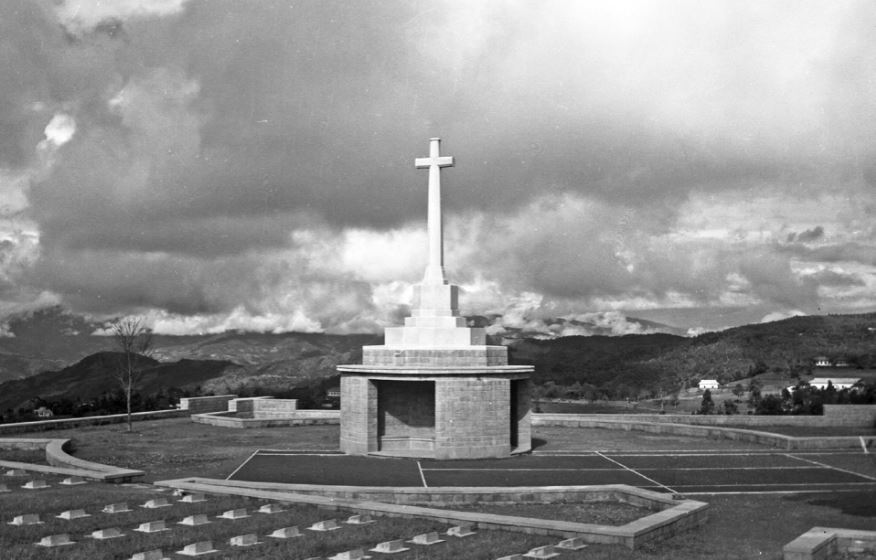

Oakes’ appointment by the IGWC would prove an astute choice as he would introduce a modernist sensibility to the various commemoration and pilgrimage sites he designed in the region, a sensibility that would later define his career. Similarly, Kranji can be framed within the wider context of similar sites that bear testament to the horrors and brutality of war. Although located in disparate countries, the shared architectural heritage of these sites gave rise to a common history with its own narrative: the advance of the Japanese campaign, its subsequent military confrontation and occupation, and eventual retreat.

Kranji War Cemetery, like other similar sites in the region, had a contested history from the outset. It was perceived as quintessentially British or “imperial” in form, sentiments not shared by a colonised populace seeking independence from their oppressors. From the IWGC’s perspective, this “sacred site” represents the fallen soldiers and airmen of the Commonwealth forces in the war against the Japanese.

The bodies interred and names inscribed at Kranji reflect a foreign enterprise far removed from their places of origin. Kranji also bears testimony to its uncomfortable position within a society that is culturally different from the West. As a result, the cemetery has become relatively isolated, bereft of visitors as well as the accompanying vigils and commemoration services that might occur at the better known and more frequently visited war cemeteries and memorials of Western Europe.

Over the years, the literature on Kranji has placed the war cemetery and memorial within various scholarly frameworks. Edwin Gibson and G. Kingsley Ward’s Courage Remembered (1989), Philip Longworth’s The Unending Vigil (1967) and Julie Summers’ Remembered: A History of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (2007), nominally view Kranji through a Eurocentric lens, as an effect of the institution and its ideals. It is one of the few cemeteries created from the “distant” war against Japan, yet somehow fitting in within the wider war graves endeavour.

Outside the “imperial” view, the most comprehensive book written on Kranji is by Singaporean journalist Romen Bose. Titled Kranji: The Commonwealth War Cemetery and the Politics of the Dead (2006), the book offers the first insight into the establishment of the cemetery from the perspective of its host country.4 It details all of Kranji’s individual memorials and explores the politics of its approval and funding, along with the official unveiling of the Singapore Memorial. The publication also marks an important shift in the local perception of Kranji.

From the late 1980s onwards, there was renewed interest from both the public and state over the battlefield history of the Japanese invasion and occupation of Singapore. New literature on the subject gave rise to a national discourse on Singapore’s post-colonial history, raising important questions on national identity.5 Academics Brendah Yeoh and Hamzah Muzaini have described the prevailing literature as tending to “analyze these spaces of memory as loci of ‘personal’ mourning or as symbolic manifestations of imperial identities”.6

The Imperial War Graves Commission in Asia

Barely two months after the surrender of the Japanese and the end of World War II, three senior officers of the British Army gathered at Croydon Airfield in South London on the wintry morning of 14 November 1945. The men had been tasked by the IWGC to travel to India, Burma and the Far East to visit sites that had witnessed some of the heaviest battles of the war and assess the burial sites where their fallen comrades had been laid to rest. They would then recommend the suitability of these sites in becoming permanent war cemeteries.

Accompanying the IWGC’s Deputy Director of Works, Major Andrew MacFarlane, was Colonel Harry N. Obbard,7 seconded from the army as the Inspector for India and Burma, and Major Colin St Clair Oakes, an architect recently discharged from active service. The itinerary included visits to all known military cemeteries so that the advisory architect could make proposals for their general layout and architectural treatment. The men would also traverse the Siam-Burma Railway and advise on the number, location and layout of military cemeteries from this dark episode of World War II. Covering over 26,000 miles by air, rail, road and water, the trip would conclude in Singapore. It would be late February 1946 before the team returned to London.

Despite having to contend with the difficulty of travelling in war-ravaged countries, the party managed to visit hundreds of burial sites – many hastily prepared by the army graves service units – in five countries and over 50 cities within the space of just three months. Working around the clock with little rest, Oakes was forced to write his notes and prepare sketches under hurricane lamps well into the night. Yet, in spite of the personal discomforts of the trip, the conceptual ideas for the present-day Commonwealth War Cemeteries in India, Burma, Bangladesh, Thailand and Singapore had been cast.

Kranji: The Final Choice

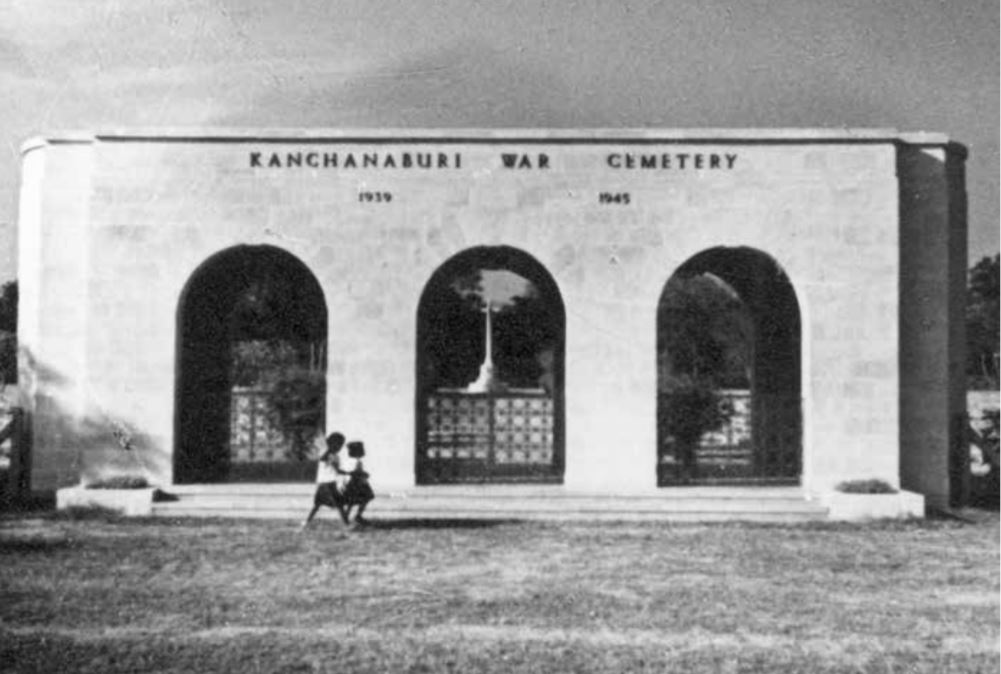

A long-standing policy of the IWGC was to select sites that were the scene of significant battles or were associated with disturbing but significant memories. The scholar Maria Tumarkin, in her book Traumascapes (2005), identified the places upon which war cemeteries are founded as bearing the tangible imprint left behind at a place of violent suffering or “traumascape”.8 Obbard and Oakes were aware of this policy. In their initial tour of Asia, they were asked to identify sites that could be built as war cemeteries. Notable examples in this regard were Kohima and Imphal in India, Chungkai and Kanchanaburi in Thailand, Thanbyuzayat in Myanmar, and Sai Wan Bay in Hong Kong.

Arriving in Singapore on 6 January 1946, Obbard and Oakes would meet Colonel Foster Hall, the British Army’s Deputy Director of Graves Registration & Enquiries, and were also briefed by Lieutenant-Colonel A.E. Brown, the recently appointed head of the Australian War Graves Service.9 Over the next seven days, they visited burial grounds at Buona Vista, Changi, Nee Soon, Melaik (located north of the former Mental Hospital along Yio Chu Kang Road), Wing Loong, Point 348 (Bukit Batok Hill) and Kranji. Their primary task was to critically assess the suitability of the existing burial sites and select one place where all the Allied war graves on the island could be consolidated and re-interred permanently. Oakes would then assess each location and compile the final report for the IWGC.

Buona Vista, situated high up in a cluster of hills about five miles to the west of the port, had few trees but possessed excellent coastal views. However, its sandy soil and water run-off were problematic. Melaik, on the other hand, would be the most centrally placed cemetery on the island but was unfortunately enclosed within a dense plantation of rubber trees and the site hemmed in on three sides by building development. On the fourth side, across the road, it adjoined the mental asylum and leper colony.

Wing Loon, located at the eastern end of the island near Changi Prison and accessible by a semi-private road, had much to commend it with its views of the sea. But it would entail securing permanent access rights to the road and additional sea-fronting land to its south; this site was later ruled out due to the difficulty of acquiring land.

Nee Soon, Changi and Kranji had existing cemeteries. Nee Soon was situated on sloping ground facing the Seletar River estuary, about 400 yards from the main road. Oakes had identified Nee Soon as a “pleasant and suitable” site for a war cemetery, but agreed with Obbard that it was better retained as a permanent Muslim War Cemetery given the large number of Muslim graves at this site.

Changi cemetery, established during the Japanese Occupation by POWs incarcerated at the adjacent Changi Prison, was Obbard’s original choice for the Combined Allied Christian War Cemetery in Singapore.10 Its well-tended graves told a tragic history that was well suited for memorialisation. However, as it was located adjacent to the runways of Changi Aerodrome, which the Royal Air Force was enlarging, it was precluded from consideration as it would involve removing and re-interring the existing graves.

Ironically, Kranji cemetery, located within the grounds of a former POW hospital overlooking the Johor Straits, was not even considered in the first place. “Difficult cemetery to expand and situation not exceptional”, reported Oakes.11 Obbard too concurred that Kranji, along with Buona Vista, as being “surrounded by jungle and are on very sandy soil, and would be costly to construct… [besides] there are no special historical associations with these two sites at Buona Vista and Kranji”.12

It was, in fact, a small yet prominent hill in central Singapore that captured Oakes’ imagination and fulfilled all the necessary requirements. At a height of 104 ft, Point 348, also known as Bukit Batok Hill, overlooked Ford Motor Factory, site of the Allied surrender to the Japanese. Tall and conical in shape, it was well situated along the main road connecting Singapore town to the Johor Straits. The summit had been levelled and extensively terraced with a wide road built to access it, all constructed by Australian POWs.

During the early days of the Occupation, the Japanese had used the same labour force to erect a war memorial and a Shinto shrine known as Syonan Chureito on its summit to commemorate their war heroes. In a small gesture to the prisoners, the Japanese had allowed the Allied forces to build a memorial to honour their war dead; this comprised a 15-foot-tall wooden cross behind the Shinto shrine. Both were destroyed when the Japanese surrendered, and only two entrance pillars and a steep flight of 120 steps leading to the summit remained when the officers arrived to assess the site.13

In his report submitted to the IWGC, Oakes identified Point 348 as the site most suited for the development of the permanent war cemetery in Singapore. Writing to headquarters, he said:

“The site is one of the most impressive imaginable. From the summit, the views across the whole island, and to the sea beyond are superb…. Taking into consideration all factors, POINT 348 is probably the best site for the proposed Allied Christian Cemetery. With it could well also be combined a memorial to the missing from that theatre of operations.”14

The “factors” Oakes referred to were, in fact, three minor difficulties he foresaw in shaping the hill for its new role as a war cemetery. Aside from the existing terracing which was unable to accommodate the almost 2,500 estimated war graves, there was the “large unsightly factory with tall chimneys, which at present disfigures the main axis and proposed cemetery approach”.15 Both, however, were not obstacles to Oakes. To accommodate additional war graves, he recommended levelling the lower slopes of the hill to create more terraces, and as for the “unsightly” factory, he proposed screening it out with a gently sloping carriageway winding around the hill along with suitable plantings.

It was the third difficulty that proved insurmountable. Given the presence of the Japanese shrine, Oakes noted that “its previous association as an enemy memorial might be considered objectionable”.16 Obbard recognised the sensitivities associated with the site and, in the end, recommended that Changi be the preferred choice for the war cemetery, with Nee Soon to be retained for the Muslim war graves.

However, soon after the men left Singapore, they were informed that additional land required for establishing a war cemetery at Changi could not be secured. Instead, the Royal Air Force had demanded the urgent removal of the graves in the cemetery so that the airport could be expanded. Obbard then revised his recommendation in line with Oakes’:

“This hill [at Point 348] forms actually the best of all the sites we saw for a cemetery. We did not suggest it in the first place because its previous use as a Japanese memorial hill might be regarded as objectionable; but, if the Changi site is not available, then we strongly recommend the adoption of this hill site, on which a most impressive cemetery can be formed, and on which also a memorial to the missing could very well be set up. The advisory architect is preparing a suggested layout on this site.”17

However, in the subsequent chaos of the aftermath of the war and in spite of the uncertainty of the Changi site, the IWGC went ahead to recommend it as the permanent war cemetery for Singapore. This decision carefully avoided the sensitivities Point 348 would have generated among locals and returning service personnel. But it would be a short-lived decision, for HQ Air Command South East Asia had proceeded with extending the airport at Changi in the meantime and would not guarantee building near the earmarked site. With both sites Obbard and Oakes had recommended declared unsuitable, Kranji, which had been placed well down on their lists, was selected as a suitable compromise.

Work on establishing Kranji as a war cemetery began in April 1946, with all available clues to the locations of other grave sites in Singapore followed up. Search workers from the Graves Units in Australia and the United Kingdom were despatched to Singapore, but the lack of manpower to physically dig and relocate graves made progress painfully slow. Returning Singaporean residents assisted in the effort to locate and identify graves and remains. It was not until the end of 1946, some 16 months after the Japanese surrender, that all the war graves on the island had been exhumed and moved to Kranji.

Post-War Developments

Colin St Clair Oakes would not see through the completion of Kranji War Cemetery, nor attend the unveiling ceremony of his “winged” memorial. By the late 1940s, he had taken up a partnership at Sir Aston Webb & Son, and rejoined the Architectural Association. In 1949, with a young family and having endured years away during the war, followed by months travelling for the IWGC, Oakes was appointed Chief Architect of Boots Pure Drug Company,18 continuing his predecessor’s work in rebuilding the many Boots stores in England that were destroyed during the German bombings.

KANJI’S WAR DEAD

Named after the local tree, pokok kranji or keranji, Kranji is situated in the north of Singapore, on a small hill with commanding views over the Straits of Johor. The British first established a military base in this area in the 1930s, which also served as a depot for armaments and ammunition during the early days of World War II. When the Japanese attacked Singapore by air on 8 December 1941, the camp was turned into the battalion headquarters for the Australian forces. On 9 February 1942, Kranji was defended by the Australian 27th Brigade and a company of Chinese Dalforce volunteers when the Japanese first landed on Singapore soil at nearby Kranji Beach.

During the Japanese Occupation, Kranji camp was appropriated as a field hospital for the Indian National Army (INA) until its departure in 1944. The camp was then modified to accommodate returning POWs from the SiamBurma Death Railway as well as large numbers of sick and injured POWs transferred from Changi Prison. As with the small hospital at Changi, the makeshift “Kranji Hospital” also established a small cemetery for those who died within its care. When the war ended, this simple hospital graveyard would be expanded to become Singapore’s main war cemetery.

In early 1946, the Imperial War Graves Commission (IWGC) would send officers and an architect to Singapore to advise on the general layout of Kranji for its impending transformation into a war cemetery and a memorial to the missing. Yet, plans for the present-day cemetery would not materialise immediately. As the IWGC had a long-standing policy of not taking over any remains that could not be satisfactorily proven as entitled to a war grave burial, there was a protracted impasse over identifying the remains of both combatants and non-combatants.

Across the causeway, the Malayan Emergency and numerous post-war independence movements in Asia seeking sovereignty from colonial rule would see further delays. It would take more than 10 years and the involvement of various parties, the British Army and War Office, the British Colonial Office, the IWGC and the Singapore government, before the Kranji War Cemetery and Memorial was officially unveiled on 2 March 1957.

Today, Kranji contains the remains of 4,461 Commonwealth casualties of World War II from numerous burial sites spread across Singapore, including graves relocated from Changi, Buona Vista and Bidadari. The Chinese Memorial marks the collective grave for 69 Chinese servicemen killed during the Occupation in 1942. In addition, there are the Singapore (Unmaintainable Graves) Memorial, Singapore Cremation Memorial and the Singapore Civil Hospital Grave Memorial; the latter commemorates more than 400 civilians and Commonwealth servicemen buried in a mass grave on the grounds of Singapore General Hospital. The Kranji Military Cemetery, which is the resting ground for non-world war burials, adjoins to the west.

The most visible structure is the Singapore Memorial, designed to reflect an aeroplane with its 22-metre (72-ft) central pylon and wing-shaped roof supported by 12 stone-clad pillars inscribed with the names of over 24,000 casualties who have no known graves. It is dedicated to servicemen from the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, Ceylon, India, Malaya, the Netherlands and New Zealand.

Annual memorial services are held at the Kranji War Cemetery on Remembrance Day and ANZAC (Australian and New Zealand Army Corps) Day. The Remembrance Day ceremony is traditionally held on the second Sunday of November to honour those who sacrificed their lives in war. ANZAC Day takes place on 25 April.

REFERENCES

Blackburn, K., & Hack, K. (2012). War Memory and the making of Modern Singapore (p. 110). Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING 940.53595 BLA-[WAR])

Bose. R. (2006). Kranji: The Commonwealth war cemetery and the politics of the dead. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions. (Call no.: RSING 940.54655957 BOS-[WAR])

Commonwealth War Graves Commission (2018). Kranji War Cemetery. Retrieved from Commonwealth War Graves Commission website.

Lane, A. (1995). Kranji War Cemetery, Singapore. Stockport, Cheshire: Lane Publishers. (Call no.: RSING 940.54655957 LAN-[WAR])

Longworth, P. (1967). The unending vigil: A history of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. London: Constable. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Colin St Clair Oakes, the architect with the Imperial War Graves Commission responsible for designing a number of cemeteries located across South and Southeast Asia. These include Kranji War Cemetery in Singapore; Taiping War Cemetery in Malaysia; Kanchanaburi War Cemetery and Chungkai War Cemetery, both in Thailand; Rangoon War Cemetery in Burma; Imphal War Cemetery and Kohima War Cemetery, both in India; Sai Wan Bay Cemetery in Hong Kong; and Chittagong War Cemetery in Bangladesh. Courtesy of the Oakes Family Collection.

Colin St Clair Oakes, the architect with the Imperial War Graves Commission responsible for designing a number of cemeteries located across South and Southeast Asia. These include Kranji War Cemetery in Singapore; Taiping War Cemetery in Malaysia; Kanchanaburi War Cemetery and Chungkai War Cemetery, both in Thailand; Rangoon War Cemetery in Burma; Imphal War Cemetery and Kohima War Cemetery, both in India; Sai Wan Bay Cemetery in Hong Kong; and Chittagong War Cemetery in Bangladesh. Courtesy of the Oakes Family Collection.

Born 23 May 1908, in the village of Tanyfron in north Wales, the childhood of Colin Sinclair Rycroft Oakes was bookended by the achievements of the Victorian age and the catastrophe of World War I. This was a period that also ushered in new attitudes to function and style – a movement that otherwise became known as Modernism.

Admitted to the Northern Polytechnic School of Architecture in 1927, Oakes would come under the tutelage of British abstract artist and pioneer of Modernism, John Cecil Stephenson. The polytechnic would instil in him a cosmopolitan outlook and design temperament that veered towards the contemporary. It also inspired his first overseas foray, departing in April 1930 for Helsinki, Finland, to join the practice of architect Jarl Eklund. Eklund would also mentor a young Eero Saarinen, one of the great architects of the 20th century.

Oakes’ return home in 1931 would prove short-lived. His application to the prestigious Rome Scholarship in Architecture, offering an opportunity to live and study at the British School at Rome, was successful. Travelling to the historic cities of Europe and producing detailed measured drawings from archaeological sites, Oakes’ work would be exhibited at the Royal Academy, and see his scholarship extended for a second year. It would also be the last, as by 1932, Italy’s fascist regime, coupled with rising anti-British sentiments, had created an environment of hostility.

By spring of 1936, Oakes once again left England, this time for India. Appointed Second Architect to the Government of Bengal, he would quickly assume the role of Acting Government Architect, responsible for the design of numerous public projects such as the Calcutta Custom House, expansion of Dum Dum Jail, and technical colleges in Dacca and Chittagong. His design contribution included three bridges, notably the iconic SevokeTeesta Bridge spanning the Teesta River.

Oakes’ experience of living in India, along with membership of the Territorial Army during his youth, would prove beneficial to the British Army when the Japanese entered World War II. Commissioned as a Captain, Oakes’ posting to Bengal would see his active involvement in the Allies’ Arakan Campaign into Burma. For his role in the campaign, Oakes was bestowed an MBE in May 1944 and promoted to the rank of Major.

Shortly after the end of the war, Oakes came to the attention of Sir Frederic Kenyon, Director of the British Museum and Artistic Advisor to the Imperial War Graves Commission (IWGC). On 2 November 1945, Oakes was invited to undertake a three-month-long tour of the very regions he had recently lived and fought in – along with Ceylon (Sri Lanka), Siam (Thailand), Malaya and Singapore – on behalf of the IWGC.

It would culminate with his appointment as a Principal Architect of IWGC, and tasked with the design of numerous war cemeteries and memorials in Asia. These edifices would later prove to be his defining body of work, bringing together all that he had learnt from his past. In accepting the position, Oakes would follow in the footsteps of his predecessors but, unlike them, he would become the only Principal Architect who had served in the recent war.

Athanasios Tsakonas is a practising architect with degrees from the University of Adelaide and the National University of Singapore. This essay is a precursor to his book on Colin St Clair Oakes, the Principal Architect from the Imperial War Graves Commission who designed many of the war cemeteries found in South and Southeast Asia.

Athanasios Tsakonas is a practising architect with degrees from the University of Adelaide and the National University of Singapore. This essay is a precursor to his book on Colin St Clair Oakes, the Principal Architect from the Imperial War Graves Commission who designed many of the war cemeteries found in South and Southeast Asia.

NOTES

-

Hall, N. (1957, March 3). Thoughts of the past move 81-year-old war heroine to tears. The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Blackburn, K., & Hack, K. (2012). War memory and the making of modern Singapore (p. 110). Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING 940.53595 BLA-[WAR]) ↩

-

Dalforce was a volunteer army whose members were recruited from among the ethnic Chinese community in Singapore. It was formed in December 1941 and named after its commander, Lieutenant Colonel John Dalley of the Federated Malay States Police Force. See National Library Board. (2014, August 19). Dalforce written by Chow, Alex. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia; Mdm Cheng and Sim Chin Foo’s aliases courtesy of Kevin Blackburn in written communication, 24 April 2018. ↩

-

Private Sim Chin Foo, Dalforce, Service no. DAL/46, died 1 September 1942, col. 399, Singapore Memorial. ↩

-

Bose. R. (2006). Kranji: The Commonwealth war cemetery and the politics of the dead. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions. (Call no.: RSING 940.54655957 BOS-[WAR]) Kranji would later be included as a chapter in Bose’s 2012 book. See Bose, R. (2012). Singapore at war: Secrets from the fall, liberation & aftermath of WWII. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions. (Call no.: RSING 940.5425 BOS-[WAR]) ↩

-

Lee, A. (2015, November 9). A case of renewed identity: The fading role of WWII in Singapore’s national narrative. Retrieved from Singapore Police Journal website. Lee asserts that the war memory in Singapore is political rather than emotional. Singapore’s abandonment by the British and subsequent occupation by the Japanese was used to emphasise self-reliance and the concept of “total-defence”, and the importance of a strong national identity. ↩

-

Hamzah Muzaini & Yeoh, B.S.A. (2007, June). Memory-making ‘from below’: Rescaling remembrance at the Kranji War Memorial and Cemetery, Singapore. Environment and Planning, 39 (6), 1288–1305, p. 1288. Retrieved from ResearchGate website. ↩

-

Harry Naismith Obbard (1898–1970) was commissioned into the Royal Engineers during World War I. Seconded to the Indian Army in 1924, he was serving on the staff of GHQ, New Delhi, when he was loaned out to IWGC for the tour of India, Burma and the Far East. By November 1946, Obbard had been promoted to Brigadier and appointed Chief Administration Officer, IWGC India, Pakistan and Southeast Asia District, overseeing all the Commission’s works in the region, including French Indo-China and Hong Kong. ↩

-

Tumarkin, M. (2005). Traumascapes: The power and fate of places transformed by tragedy (pp. 10–11). Melbourne: Melbourne University Press. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

CWGC SDC 97 Box 2004. Obbard’s Tour Reports 1945–46. Annexure 2. The meeting also included British Army officers Major-General K.G. McLean and Major-General Denning. Foster Hall at the time was heading the Graves Registration Units, undertaking the recovery and concentration of remains found in Burma and along the Siam-Burma Railway. Brown would in a few years be appointed Secretary-General of the IWGC, heading up the ANZAC Agency responsible for the war graves throughout Australia, Indonesia, Borneo, Papua New Guinea, the Pacific and Japan. ↩

-

CWGC SDC 97 Box 2004. Obbard’s Tour Reports 1945– 46. Annexure 6, In his notes on the selection of sites for permanent military cemeteries on Singapore, Obbard highlights that Foster Hall’s original proposal was for three Christian cemeteries at Buona Vista, Kranji and Changi, and one Muslim cemetery at Nee Soon. Agreeing on Nee Soon for the Muslim site, Foster Hall indicated it contained the ashes of Hindu cremations and the need to scatter them. ↩

-

CWGC Add 1/6/17 Box 2003, Oakes report,Nov–Dec1945. ↩

-

CWGC SDC 97 Box 2004,Obbard’s Tour Reports1945–46. ↩

-

Bose, 2006, pp. 47–50. Also referred to as the Bukit Batok Memorial, and along with the Allies’ memorial cross, it was constructed under the engineering commander-in-charge Yasugi Tamura, using 500 Australian prisoners-of-war from the Sime Road and Adam Park camps. ↩

-

CWGC Add1/6/17 Box 2003, Oakes report,Nov–Dec 1945. ↩

-

CWGC Add 1/6/17 Box 2003,Oakes report,Nov–Dec1945. ↩

-

CWGC Add 1/6/17 Box 2003,Oakes report, Nov–Dec 1945. ↩

-

CWGC SDC97 Box 2004,Obbard’s Tour Reports 1945– 46. In a special note to Annexure 6. ↩

-

Beacon, October 1949. In-house publication of Boots Pure Drug Company. Oakes joined Boots in 1949, with an arrangement with the IWGC to hand over part of the outstanding war cemeteries whilst committing to completing the remainder. This arrangement would conclude on 31 March 1953. ↩