The House of Ripples

Martina Yeo and Yeo Kang Shua piece together historical details of the little-known River House in Clarke Quay and discover that it was once a den for illicit triad activity.

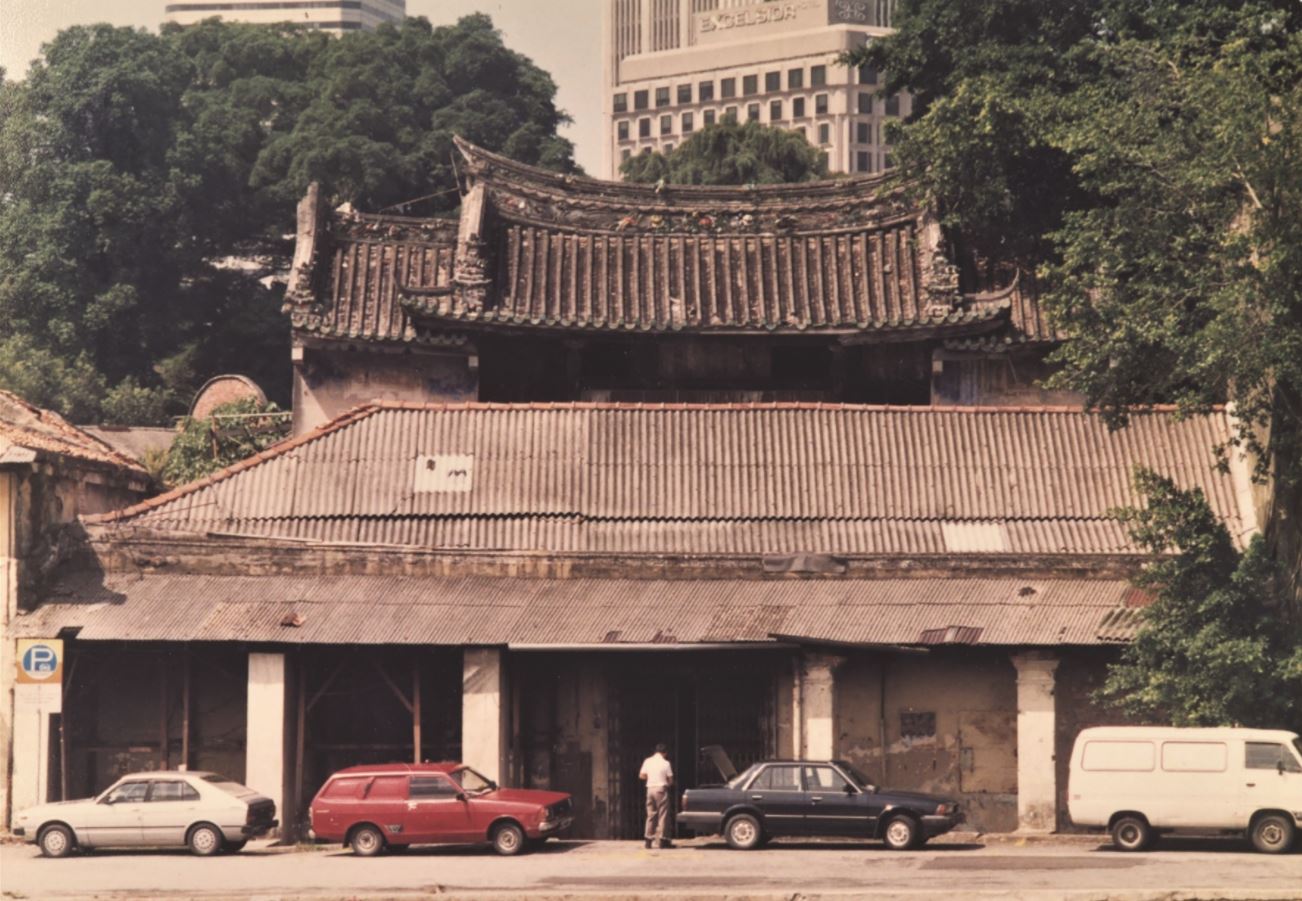

Walking along the Singapore River – where godowns (warehouses) lining its banks were a ubiquitous sight in the 19th and 20th centuries – one building strikes the casual observer as being atypical. Designed in the southern Chinese style with a prominent tiled roof and a curved ridge embellished with ceramic shards, the building is stylistically different from the others in the area. This is River House along Clarke Quay, poetically known as “House of Ripples” or Lianyi Xuan (涟漪轩) in Chinese.

Until very recently, River House was believed to have been built in the 1880s by Tan Yeok Nee (陈旭年), a wealthy Teochew gambier and pepper merchant. The house is a two-storey building with its front entrance facing the Singapore River. Unlike traditional southern Chinese mansions, however, the house is devoid of a detached entrance gateway that aligns with the edge of the street and typically leads to a forecourt.

Around the same period, Tan Yeok Nee also ordered the construction of another elaborate Chinese-style mansion along present-day Clemenceau Avenue – which has since been preserved as a national monument and is known as the House of Tan Yeok Nee. Given the geographical proximity of the two dwellings (they are only about one kilometre apart) and the similar architectural styles and approximate construction periods they shared, one wonders why Tan built the two residences so close to each other. More interestingly, it calls to question whether River House was even built by Tan in the first place.

River House has had different addresses over the course of its history: at first Municipal No. 3 North Campong Malacca (also concurrently as Warehouse No. 3 North Campong Malacca) in the late 19th century, followed by 13 Clarke Quay, and today, 3A River Valley Road. Its original address and location within the traditional commercial and godown district suggests that River House served as or was perhaps even originally built as a warehouse, as opposed to a private residence. An examination of the land leases and architectural history of the building will shed light on its owners, design, purpose and subsequent development.

Shady Beginnings

River House occupied eight parcels of land, five of which form the grounds of the main building. The land leases for these five plots were issued by the British East India Company to two different people between 23 July 1851 and 1 November 1855. The leases for the remaining three plots, which stretched from the main building to the now expunged vehicular road known as Clarke Quay, were issued only on 26 October 1881. All were 99-year leases.

An 1863 photograph taken by Sachtler & Co. and another dating from the mid-1860s show the land being occupied by a two-storey masonry building and several smaller single-storey houses. Surrounding the structures were swampy grounds with houses on stilts clearly visible on the opposite river bank.

The two-storey building in these photographs cannot be River House as it is stylistically different in form and much smaller than the building we see today. In fact, River House had not yet been built in the 1860s. It was only in July 1870 that the five land leases of the main house were consolidated under a single ownership comprising three individuals. This possibly marks the earliest date of construction. Given that the earliest building plans of private buildings held by the National Archives of Singapore date from 1884 and that no original building plan of River House has ever been found, it is possible to surmise that the house was likely built sometime between 1870s and 1883.

What’s more, there is no indication from archival records that River House was ever owned or leased by Tan Yeok Nee. The three owners in 1870 – Choa Moh Choon (蔡茂春), Lee Ah Hoey (李亚会) and Neo Ah Loy – had interesting backgrounds and were likely unrelated to each other as they had different family names.1 The probable identities of two of these owners, however, provide a clue as to what the house could have been used for.

From as early as 1854 until his death on 10 January 1880, a man named Choa Moh Choon was known to be the headman of the notorious Ghee Hok Society (also known as Ghee Hok Kongsi; 义福公司). Based on evidence, such as the date of Choa’s death (as indicated in the Straits Settlements Government Gazette and various land transactions), it is highly likely that the owner of the land in 1870 where River House was subsequently built and the headman of the Ghee Hok Society were one and the same person.

Choa was born in the Teo Yeo (潮阳) district of the Teochew prefecture (Guangdong province) in China and arrived in Singapore in 1838 when he around 19 years old. His official occupation was listed as “Doctor and Theatre Manager” after it became compulsory for secret societies and their headmen to register themselves.2 In actual fact, Choa was known to be involved in illegal activities. He operated brothels and framed a man who wanted to leave the Ghee Hok Society, causing the latter to be imprisoned for two years.

After Choa’s death, the aforementioned Lee Ah Hoey (one of the other title deed owners) became the society’s new headman. On official records, Lee was a “Rice Shop Keeper and Manager of Theatre”, but in reality, he was better known as the ringleader of the failed 1887 attempt to murder William A. Pickering, the first Chinese Protector of Singapore.3 As part of Pickering’s job was to stamp out Chinese triad activity in the colony, he made many enemies in the community.

Lee was subsequently tried and banished from the Straits Settlements on 12 October 1887, leaving the leadership of the Ghee Hok Society with no clear successor.4 Before Lee left Singapore, he appointed one Lee Yong Kiang (李永坚) to handle matters pertaining to River House. An Indenture of Mortgage dated 7 February 1890 between Lee Ah Hoey and Hermann Naeher of Lindau, Germany, indicates that Lee Ah Hoey was purportedly residing in China at the time the document was signed and that Lee Yong Kiang was acting on his behalf. Sometime between 7 February 1890 and 1892, Lee Ah Hoey had surreptitiously returned to Singapore. He was subsequently caught and deported for life in October 1892.

As for the third owner Neo Ah Loy, little is known about him. When the five land parcels were mortgaged in August 1873, the names listed on the mortgage document were Choa Moh Choon, Lee Ah Hoey and Leang Ah Teck (梁亚藉), suggesting that Neo Ah Loy might also have gone by the name Leang Ah Teck. This is not an improbable supposition given that Neo and Leang are Teochew transliterations of the family name Liang (梁).

A “Secret Society” House

Since two of its three owners were headmen of the infamous Ghee Hok Society, could River House have been or intended to be its new kongsi (secret society) house? Or was it purely coincidental that they were joint owners?

The Ghee Hok Society was predominantly made up of Teochews. It is believed to have been founded around 1854 by those involved in the “Small-Dagger” (厦门小刀会) rebellion in Amoy (Xiamen), China, who fled to Singapore after the movement failed. The Ghee Hok was one of several societies that made up the Ghee Hin Kongsi in Singapore – where it was variously known as the Heaven and Earth Society (Tiandi Hui; 天地会) and the Triad – whose main objective was to overthrow the Manchus and restore the Ming dynasty in China. Despite being part of the same umbrella organisation, the Ghee Hok Society engaged in frequent clashes with rival Ghee Hin triads.

In the decades leading up to the 1880s, the membership of the Ghee Hok Society grew from 800 in 1860 to 14,487 in 1889, the year before it was dissolved. Society members included those involved in illicit businesses as well as ordinary folks such as small-time hawkers and peddlers. Before 1886, the society’s registered address was 25-4 Carpenter Street, during which time it frequently clashed openly with rival societies in the area – such as the Say Tan (姓陈), Say Lim (姓林) and Hai San (海山).

On official records at least, there is no reference to River House serving as the Ghee Hok Society’s headquarters before 1886. From 1886 until its dissolution in 1890, the society was located at 3 River Valley Road, which was very near the junction of River Valley Road and Hill Street. It is possible that the leaders of the society were searching for a new site near Clarke Quay, presumably for easier access to the port facilities of the Singapore River. Both the official old and new headquarters – first at Carpenter Street and then at River Valley Road – were very small units and seemed rather unbefitting for such a large society. If this was the case, River House could have served as the unofficial headquarters of the Ghee Hok Society.

In December 1880, an earlier loan that was taken up before Choa Moh Choon’s death, and which used the house as collateral, was repaid in full. The house was then transferred to Lee Ah Hoey, Teng Seng Chiang (郑成章) and Koh Hak Yeang (许学贤) at the behest of the two remaining original owners, Lee Ah Hoey and Neo Ah Loy. It is likely that the legal owners of the house might have held the property unofficially in trust for the Ghee Hok society. As we shall see later, this was indeed the case for a subsequent group of owners of River House.

Teochew Influences

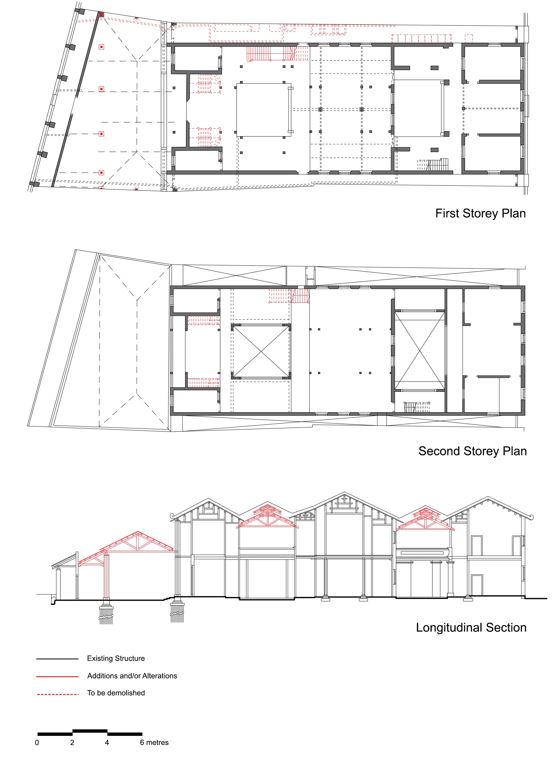

What we do know for certain is that the predominantly Teochew make-up of the Ghee Hok Society is reflected in the architectural style of River House. The building has a Teochew sidianjin (四点金) or “four-points of gold” layout, with two internal courtyards flanked by a pair of huoxiang (火巷) or fire alleys.

Traditionally, Teochew houses, especially the more elaborate mansions, contain side wings or congcuo (从厝) that extend beyond the fire alleys. The alleys serve as physical breaks that prevent fire, should one break out, from spreading easily from one part of the house to another. Additionally, these alleys provide privacy to extended families living in different sections of the house.

Side wings, however, are noticeably absent in River House. Could the owners have intended to build side wings after they had raised enough money to acquire the adjacent plots of land? Or did the owners foresee the importance of having physical breaks in an area packed cheek-by-jowl with godowns, knowing full well how fires can easily spread?

Regardless, the fire alleys were probably the reason why River House survived a raging fire that engulfed its neighbour at 14 Clarke Quay on 21 August 1920. The fire was so huge that it required 36 firefighters and three firefighting machines before it was finally extinguished. The fire alleys, which provided the only escape routes for the occupants of River House, had front and back doors. The back doors opened into Clarke and Read streets, while the front doors opened into the now expunged Clarke Quay road. The main building did not have a back door at the time.

Besides its layout, other features of River House are typically Teochew too. These include the gentle curves of its roof ridges, its structural system as well as the recessed entranceway. The roof ridges are decorated with qianci (嵌瓷), or ceramic shard ornamentations, in an array of colours. According to the 1919 building alteration plan showing the proposed alterations to the house, the roof truss system is in the tailiang style (抬梁式), which “comprises successive tiers of beams and struts in a transverse direction”.5 The ends of the granite cantilever beams on the front facade, known as jitou (屐头), are carved in a highly abstract chihu (螭虎) motif. Chihu is believed to be one of the nine sons of a dragon or long (龙). Such cantilever beams are also characteristic of Teochew architecture.

Fronting the river is the house’s recessed entranceway. It is called the aodumen (凹肚门) as the layout of the entranceway resembles the Chinese character “凹”. In traditional Teochew architecture, the recessed entranceway does not have any openings leading to the outside apart from the main door, with lime-moulded panels or huisu (灰塑) taking the place of windows. However, River House has a window on either side of the entranceway. These windows are unlikely to be later additions, as they were already in place by the time the plans for proposed alterations were drawn up in 1918 and 1919.

The centrepiece of the entranceway is a doorway framed with solid granite carved with different motifs. An examination of the geological composition indicate that the granite is possibly of local origin. The motifs include a pair of dragon-fish or aoyu (鳌鱼) carved with eyelets known as diaoliankong (吊帘孔), which were used for hanging ceremonial banners; a pair of door seals or menzanyin (门簪印) as well as a pair of incense stick holders or chaxiangkong (插香孔) embellished with a flower-and-vase motif and flanking the entrance. Traces of the green pigment used specifically in Teochew architecture can still be seen in the inscribed grooves of these motifs.

Above the door lintel, the plaque bearing the name of the house is held up by a pair of stone lions known as biantuo (匾托). The present pair of biantuo found at the house today protrude and appear to be blocking the plaque rather than elevating it; these are new and not the originals. The proportions and style of the new lions are unlike the flatter and rounder style that is typically Teochew.

In addition, the presence of a void between the plaque and the lintel is unique to Teochew architecture. The void and the plaque are currently concealed by the signage for the restaurant that currently occupies the building.

A Gambier Shed

By 1890, with the remaining owners – Teng Seng Chiang and Koh Hak Yeang – having passed away, River House came under the sole ownership of Lee Ah Hoey. As mentioned earlier, he had mortgaged the house in February 1890 to Hermann Naeher, a German who later became an honorary citizen of Lindau in southern Germany.6

When Lee defaulted on the mortgage, the house was sold to Arthur William Stiven of Stiven & Co. on 20 June 1891. This took place before Lee was deported for the second time in October 1892. Stiven subsequently sold the property to Tan Lock Shuan (陈禄选) on 7 July 1896.7 It is unclear what the house was used for under Stiven’s ownership, although his company was listed as “Merchants and Commission Agents” in the 1893 Singapore and Straits Directory, with offices at Boat Quay and Battery Road.8

Soon after Tan Lock Shuan acquired the property, he engaged an architect to design and build a gambier shed on the open space in front of the house. This open space made up the remaining three land parcels of River House, which were acquired by Lee Ah Hoey and Teng Seng Chiang in 1881. The shed remained a feature of River House for almost a century until it was demolished in the early 1990s when Clarke Quay was conserved as a heritage area.

Tan was the kangchu (港主) or headman of Sungai Machap, a pepper and gambier plantation, in Johor. From the mid-1880s onwards, large tracts of land in Johor were cleared for pepper and gambier plantations, both of which were lucrative cash crops then. The harvested crops were shipped to Singapore for processing and transhipment before being exported to the rest of the world. Tan most probably used the shed at River House for the processing, storage and trading of gambier from his Johor plantations.

The 1896 building plan of the gambier shed is significant as it shows the existence of River House by this date. No demolition of any structures in the open area in front of the main house are indicated on the building plan. It is thus unclear if there were any structures, such as a detached entrance gateway typically found in Chinese mansions, in the open space prior to 1896.

A School Campus

After Tan Lock Shuan passed away on 30 July 1908 without leaving a will, the Supreme Court of the Straits Settlements granted Letters of Administration of his estates to Tan Soo Guat (陈思悦). Three years later, on 26 July 1911, the latter mortgaged River House to Tan Tji Kong for $23,000, a handsome sum at the time. While Tan Soo Guat would make timely payments on the loan’s nine-percent interest rate, he had trouble repaying the principal sum. Fortunately, he was able to sell the house on 30 April 1913 for $24,250, which was more than enough to repay the principal sum.

The new group of owners were Leow Chia Heng (廖正兴), Chua Tze Yong (蔡子庸), Ng Siang Chew (黄仙舟) and Low Cheo Chay (刘照青), all prominent leaders of the Teochew community and trustees of Tuan Mong School (端蒙学堂).9

Chua also served as the president and vice-president of the Singapore Chinese Chamber of Commerce in 1907 and 1908 respectively. He was a wealthy merchant who made his money in the import and export of rice and sugar. Both Chua and Ng were also trustees of Ban See Soon Kongsi (万事顺公司), a small Teochew society formed in May 1847, which made significant contributions to the finances of Tuan Mong School. Low was also a staff of Ban See Soon and managed its estates. Although River House was legally held under their individual capacities, the four men were, in fact, acting for and on behalf of Tuan Mong School.

In July 1913, the school relocated to River House from 52 Hill Street after the landlord sought to increase its rent. During the graduation ceremonies of the third, fourth and fifth student cohorts in December 1914, December 1915 and June 1917 respectively, photographs were taken at the recessed entranceway of the building – to date the first extant close-up photos of the building.

The photos show huisu (灰塑) or pargetting work (decorative plastering) on the walls of the recessed entranceway in sets of three panels: upper, middle and lower. These panels were traditionally moulded from oyster-shell lime (贝灰), sometimes with paper fibre added to the mixture to improve its tensile strength and to prevent cracking. The panels were then coloured using fresco painting. By the time the first graduation photo of the third student cohort was taken at River House in 1914, the original panels had been given a whitewash. The steps leading to the house that were once visible in the photos no longer exist today, after the ground in front was raised during restoration work in 1993.

By 1917, River House could no longer accommodate Tuan Mong’s rapidly expanding student population and the school’s board of management started looking for new premises. On 26 April 1918, the building was sold to Ho Ho Biscuit Factory for $65,000 – more than two-and-a-half times the purchase price just five years earlier – and the school moved to 29 Tank Road.

In 1918 and 1919, Ho Ho Biscuit Factory submitted alteration plans to convert River House into a godown, suggesting that the house was perhaps not originally built to be a warehouse. The alterations included covering up the internal courtyards as well as reinforcements that increased the load capacity of the building. Although Ho Ho Biscuit sold the property in 1946, for the next five decades – from the 1940s to 90s – the different owners of River House continued to use it as a warehouse.

Leaving a Legacy

In 1993, River House was restored – sadly with some of its original Teochew characteristics lost in the process – and rented out as a commercial space (it is currently occupied by the VLV restaurant and lounge).

Despite its prominent location and intricate architecture, the fascinating story behind River House has been buried in the annals of Singapore’s history for too long. The evidence drawn from the National Archives of Singapore and other government agencies reveals a building with a somewhat dubious past, but nevertheless one that is intimately intertwined with the social, economic and political conditions of the time.

The location and architecture of River House bear testimony to the importance of the Teochew community in Singapore’s early trade, and the refined building traditions they brought from southern China. For nearly 150 years, River House has witnessed the rise and decline of the Singapore River as a trading centre along with various communities who made and lost fortunes along this body of water. Today, River House continues to play a similar role as successive generations recreate their own meanings while the building is repurposed for new functions.

Martina Yeo Huijun is a researcher with the Architectural Conservation Lab at the Singapore University of Technology and Design.

Martina Yeo Huijun is a researcher with the Architectural Conservation Lab at the Singapore University of Technology and Design.

Dr Yeo Kang Shua is an Assistant Professor at the Singapore University of Technology and Design.

Dr Yeo Kang Shua is an Assistant Professor at the Singapore University of Technology and Design.

REFERENCES

Deportation of Chinese towkays. (1887, October 17). Straits Times Weekly Issue, p. 14. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Blythe, W. (1969). The impact of Chinese secret societies in Malaya: A historical study (pp. 80, 259–260). London: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSEA 366.09595 BLY)

Choa, M.C. (1864). The memorial of Chuah Moh Choon of Singapore Chinese merchant [memorial]. Straits Settlements Records, W54, p. 238. (Microfilm no.: NL151)

Dunman, T. (1865) Letter to the Secretary to Government Straits Settlements Singapore. Straits Settlements Records, W54, p. 286. (Microfilm no.: NL151)

Friday, 15th March. (1872, March 28). Straits Times Overland Journal, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Friday, 16th September. (1870, September 23). Straits Times Overland Journal, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Kim, Y.J., & Park S.J. (2017). Tectonic traditions in ancient Chinese architecture, and their development. Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering, 16(1), 31–38, p. 32. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Knapp, R.G. (2010). Chinese houses of Southeast Asia: The eclectic architecture of sojourners & settlers (p. 72). Clarendon, Vt.: Tuttle. (Call no.: RSING 728.370959 KNA)

李谷僧 & 林国璋. (1936). 新加坡端蒙学校三十周年纪念册 (pp. 14, 16). 新加坡: 新加坡端蒙学校. Available via PublicationSG.

林远辉 & 张应龙. (2016). 新加坡马来西亚华侨史 (p. 392). 广东: 高等教育出版社. (Call no.: Chinese RSING 959.5004951 LYH)

Local and general. (1892, October 6). Daily Advertiser, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

M.A. Fawzi Mohd. Basri. (1984). Sistem Kangcu dalam sejarah Johor 1844–1917 (p. 51). Kuala Lumpur: Persatuan Sejarah Malaysia. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Monday, 19th September. (1870, September 23). Straits Times Overland Journal, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

National Heritage Board. (2006). Discover Singapore heritage trails (p. 25). Singapore: National Heritage Board. (Call no.: RSING 915.95704 DIS-[TRA])

Settlement of Singapore Registry of Deeds. Private Property Deeds. Singapore: Singapore Land Authority. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Sim, S. (2002, March 28). Mansion from the past. Today, p. 33. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Singapore and Straits directory for 1893. (1893) (p. 161). Singapore: Printed at the Mission Press, p. 161. (Microfilm no.: NL1180)

Singapore. Building Control Division. (1918). Additions and alterations to building, conversion into godown (cancelled) [Building plan no.: 438/1918]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website.

Singapore. Building Control Division. (1919). Additions and alterations to 13 Clarke Quay for conversion into a godown [Building plan no. 40/1919]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. Singapore. Municipality. (1921). Administration report of the Singapore municipality for the year 1920 (p. 9–H). Singapore: The Straits Times Press. (Microfilm no.: NL3410)

Singapore. The statutes of the Republic of Singapore. (1987, March 30). Ngee Ann Kongsi (Incorporation) Ordinance (Cap. 370, 1985 Rev. ed.). Retrieved from Singapore Statutes Online website.

Song, O.S. (2016). One hundred years’ history of the Chinese in Singapore: The annotated edition (p. 487). Singapore: National Library Board. Retrieved from BookSG.

Straits Settlements Government Gazette. Singapore: Government Printing Office. Retrieved from BookSG.

Straits Settlements: Office of Inspector-General of Police. (1872, October 12). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Survey Department, Singapore. (1870–1890). Land divisions at Clarke Quay and North Boat Quay [Survey map] [Accession no.: SP000037]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website.

Survey Department, Singapore. (1958). Sub-Division No.9, Block No.1 [Survey map] [Accession no. SP002158]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website.

The late attack upon the Protector of Chinese. (1887, September 7). Straits Times Weekly Issue, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Trocki, C.A. (2007). Prince of pirates: The temenggongs and the development of Johor and Singapore, 1784–1885 (pp. 101–102, 117–119). Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.5103 TRO)

颜清湟. (2007). 从历史角度看海外华人社会变革 (p. 151). 新加坡: 新加坡青年书局. (Call no.: Chinese RSING 959.004951 YQH)

NOTES

-

Choa Moh Choon was also spelled as Choah Moh Choon, Chua Moh Choon and Chuah Moh Choon. He was also known as Choa Cheng Moh. In addition, Lee Ah Hoey was spelled as Lee Ah Hoy and Li Ah Hoey. ↩

-

Pickering, W.A. (1880, January 26). Report of the Chinese Protectorate, Singapore, for the year 1879 (G.N. 154). Straits Settlements Government Gazette, 14(15), p. 228. Singapore: Government Printing Office. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

Pickering, W.A. (1881, April 29). Annual report on the Chinese Protectorate, Singapore, for the year 1880 (G.N. 192). Straits Settlements Government Gazette, 15(18), p. 357. Singapore: Government Printing Office. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

There was no one listed as the President of the Ghee Hok Society for 1887 in the “Table showing the Number of Chinese Secret Societies, registered under Section 3 of Ordinance No. XIX of 1869, with Situation of Meeting Houses of Members, &c., in Singapore.” Found in Pickering, W.A., (1888, April 27). Annual report on the Chinese Protectorate, Singapore, for the year 1887 (G.N. 261). Straits Settlements Government Gazette, 22(20), p. 909. Singapore: Government Printing Office. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

Kim, Y.J., & Park S.J. (2017). Tectonic traditions in ancient Chinese architecture, and their development. Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering, 16(1), p. 32. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Hermann Naeher was also spelled as Hermann Näher. ↩

-

Tan Lock Shuan was also spelled as Tan Lok Shuan and Tan Lok Swan. ↩

-

Singapore and Straits directory for 1893. (1893) (p. 161). Singapore: Printed at the Mission Press, p. 161. (Microfilm no.: NL1180) ↩

-

Chua Tze Yong was also known as Chua Choo Yong, while Leow Chia Heng was sometimes spelled as Liau Chia Heng. ↩