Wheels of Change: 1896–1970

Advertisements targeting aspiring car owners have come a long way since the first automobile was launched in Singapore in 1896, as Mazelan Anuar tells us.

The word “automobilism”, meaning the use of automobiles,1 entered the English lexicon in the late 19th century when motor vehicles emerged as a new mode of private transportation. Karl Benz’s “Patent-Motorwagen”, first built in 1885, sparked a vehicular revolution that saw animal power replaced by the internal combustion engine. Thus was born the automobile, which literally means “self-moving” car. Although the term “automobilism” has fallen into disuse, the world’s love affair with automobiles has never waned, with succeeding generations embracing it with as much enthusiasm as the early adopters.

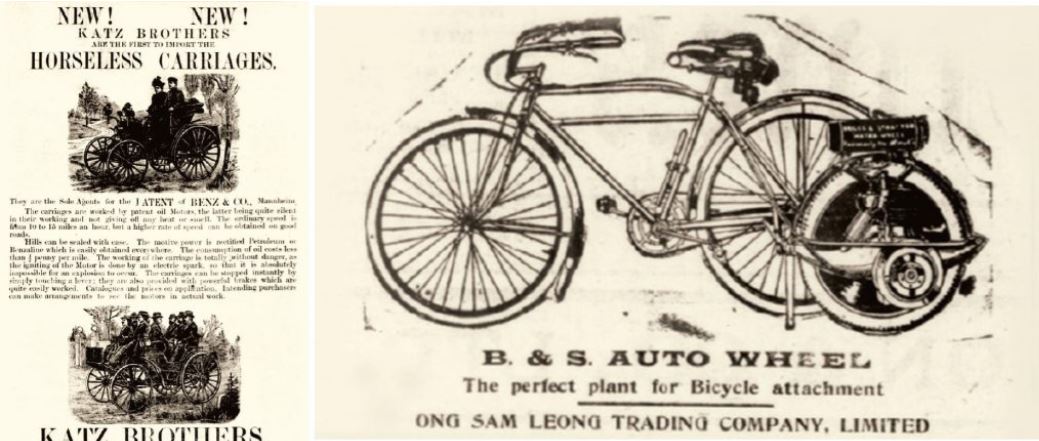

The Horseless Carriage

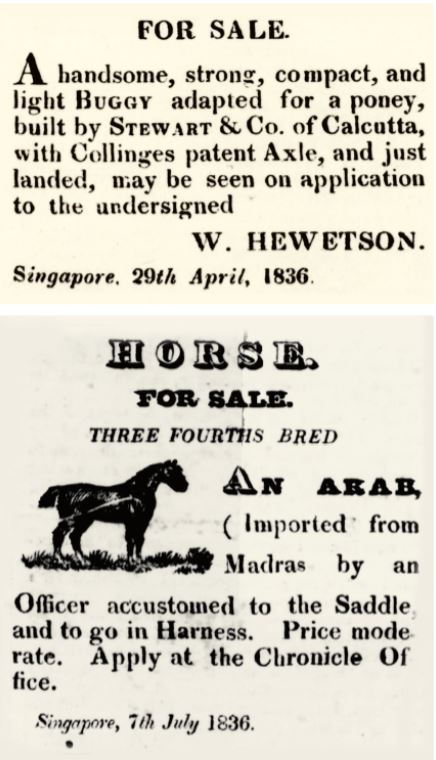

The Katz Brothers ushered in the age of automobilism in Singapore when they imported the first automobiles in August 1896. Before this, the horse-drawn carriage, shipped in from Britain since the 1820s, was a popular means of passenger transport. Another common mode of transportation in the late 19th century was the jinrickshaw (literally “man-drawn carriage” in Japanese), originally from Japan and introduced in Singapore in 1880 from Shanghai.2

The Katz Brothers were the sole agents for Benz and Co.’s “Motor Velociped”, which was advertised as a “horseless carriage”. A favourable review in The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser described it as a “neat-looking four-wheeled carriage” that did not require an “expert driver”, but commented that its $1,600 price tag was “somewhat high”.3

Automobile ads continued to make reference to “horseless carriages” for decades afterwards, and well into the mid-1950s. This was usually to draw attention to the fact that the product or company had existed since the dawn of the automobile industry and had grown in tandem with it. Examples of such advertisements included those for Dunlop Tyres, Shell (formerly the Asiatic Petroleum Company) and Chloride Batteries Limited.

The introduction of automobiles was enthusiastically embraced by the who’s who of Singapore and Malaya. A certain B. Frost of the Eastern Extension Telegraph Company and subsequently Charles B. Buckley, publisher and famed author of An Anecdotal History of Singapore, were the first to own and drive the Benz in Singapore.4 Soon, more automobiles were brought into Singapore. The Benz was followed by the De Dion Bouton and then the Albion.5

All three models shared a reputation for being very noisy and hence did not require horns to make themselves heard. Buckley dubbed his car “The Coffee Machine” because of the awful grinding noises it made.6

Who Dares Wins

Singapore’s first lady motorist was Mrs G.M. Dare, who drove a Star motorcar before switching to a two-seater Adams-Hewitt in 1906.7 That year, car registration came into force and Mrs Dare enjoyed the distinction of driving Singapore’s first registered car, which bore the licence plate number S-1.8 She nicknamed her car “Ichiban” (Japanese for “Number One”), but the locals, amazed and possibly fearful in equal measures at seeing her at the wheel, called it the “Devil Wind Carriage”.9

Even more amazing was the fact that Mrs Dare clocked more than 69,000 miles (111,000 km) driving the car all over Singapore, Malaya, Java, England and Scotland.10 She is also credited for teaching driving to the first Malay to obtain a driving licence in Singapore, a chauffeur by the name of Hassan bin Mohamed.11

The Rise of the Automobile

In 1907, the Singapore Automobile Club (SAC) was formed, with Governor John Anderson as its president. Notable members included the Sultan of Johor; Walter John Napier, a lawyer-academic who was the first editor of the Straits Settlements Law Reports; and E.G. Broadrick, president of the Singapore Municipality between 1904 and 1910 and later the British Resident of Selangor.12 Remarkably, by 1908 – when the world automobile industry was still in its infancy13 – there were already 214 individuals in Singapore licensed to drive “motor-cars, motor-bicycles and steam-rollers”.14

In June 1907, The Straits Times announced that it was devoting a special column to automobilism.15 The column started off as “Motors & Motoring” in 1910, was renamed “The Motoring World” in 1911 and ran until 1928.16 Its longevity was testimony to the fascination with cars among the paper’s readers, if not the general population.

(Right) Instead of purchasing an expensive motorcycle or an even more costly automobile, the motorised bicycle was a viable alternative for those with a smaller budget. This advertisement shows a motorised wheel attached to the rear wheel of a bicycle to make it go faster. As there were no proper traffic rules in the early 20th century, people came up with ingenious ways to travel. Image reproduced from The Straits Times, 10 March 1921, p. 2.

The monthly Motor Car and Athletic Journal was launched in March 1908, but it proved short-lived and ceased publication after 12 issues.17 It was only in the 1930s that the Automobile Association of Malaya (AAM), which SAC became a branch of in 1932, began to venture into publishing, with Malayan Motorist (first issue 1933), Motoring in Malaya (1935), Handbook of the Automobile Association of Malaya (1939) and, much later, AAM News Bulletin (1949).18 Car advertisements were regularly featured in AAM’s magazines as well as in the newspapers.

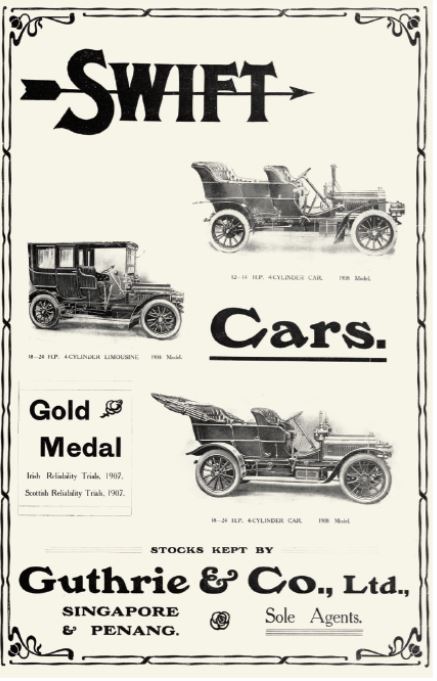

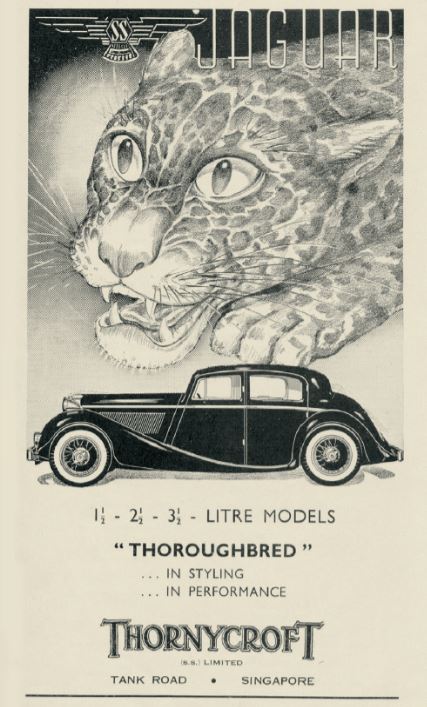

Reliability and Affordability

Up until the 1920s, car advertisements in the United States and Europe tended to highlight the vehicles’ technical features in order to familiarise potential owners with the exciting yet intimidating new world of automobile technology.19 Manufacturers recognised that scepticism about dependability and reliability were major obstacles to widespread public acceptance of motor vehicles as a means of private transportation.20

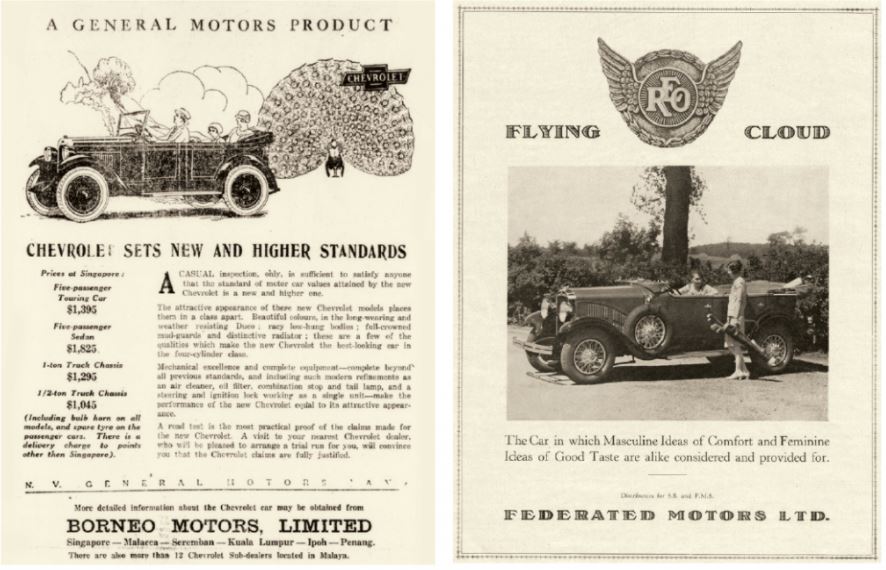

It was a similar scenario in Singapore. Distributors and agents highlighted both the reliability and affordability of their vehicles by touting the technology behind the cars and their attractive prices. There were also attempts at associating prestige with the advertised cars, but this was meant to build brand reputation and reflected the manufacturers’ ambitions rather than consumers’ desire for high-end luxury vehicles.

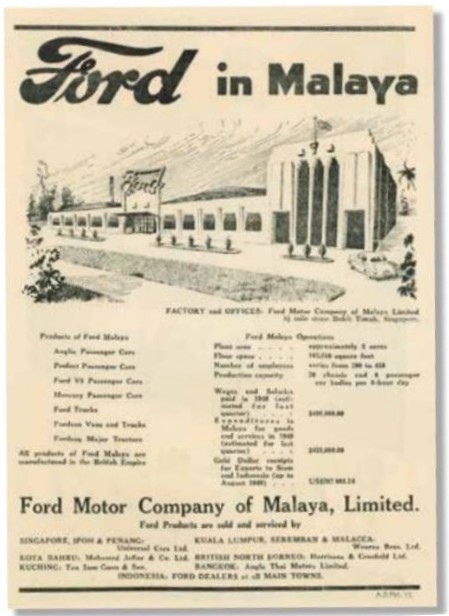

Ford in Singapore

In 1909, just a year after Henry Ford’s iconic Model T was introduced in America and took the world by storm, Ford cars entered the Singapore market.21 Initially imported by Gadelius & Company, Ford’s presence grew in Singapore when the Ford Motor Company of Malaya was established in 1926 to supervise the supply and distribution of its products in Malaya, the Dutch East Indies, Siam and Borneo.22 It initially carried out car assembly work in a garage on Enggor Street before expanding to larger premises on nearby Prince Edward Road in 1930. In 1941, the company moved to a newly built factory in Bukit Timah.23

Throughout this time, as well as in the decade following the end of World War II, Ford’s advertisements in Singapore rarely departed from its marketing tactic of playing up the efficiency of its cars and competitive pricing.

Japanese Marques

From the late 1950s, Japanese-made cars became available in Singapore. By 1970, one in two cars purchased in Singapore was a Japanese model.24 The main reason for their popularity? Value for money.

Japanese cars were much cheaper than their American and European counterparts, and were winning races in both local and international motor competitions in the late 1960s. The advertisements cleverly highlighted these achievements and, at the same time, banked on the tried-and-tested formula of good value, efficiency as well as reliability to attract buyers.

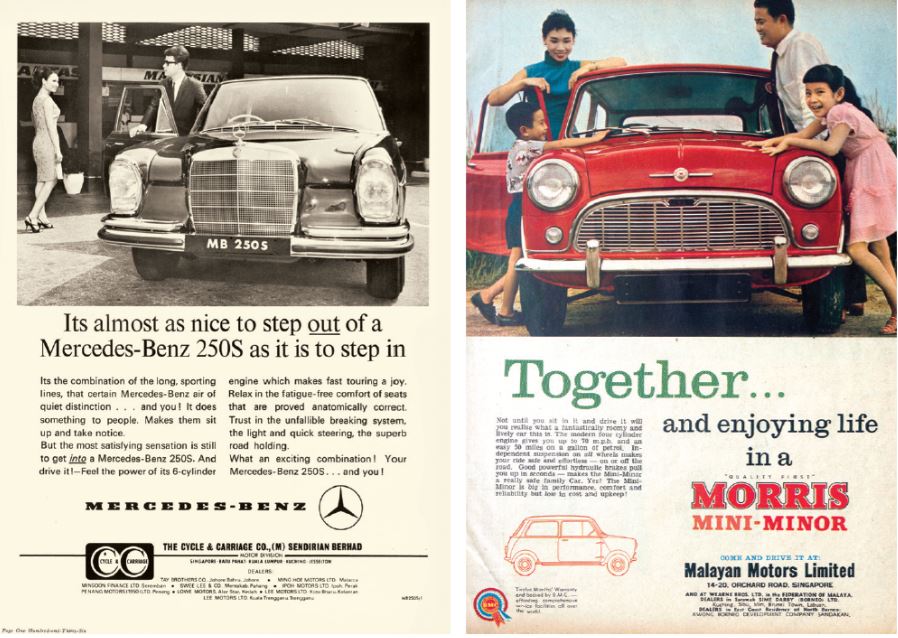

(Right) The REO Flying Cloud was advertised as appealing to the sensibilities of both men and women. Image reproduced from British Malayan Annual, 1929, p. 32.

(Right) The Renault Dauphine had every detail worked out to “anticipate the desires of lady drivers or their male consorts”. Image reproduced from The Straits Times, 15 February 1959, p. 9.

(Right) This advertisement portrays car ownership as a happy family ideal, with a picture perfect modern family admiring their brand new Morris motorcar. Image reproduced from Her World, November 1960.

First introduced in 1910, the taxi-cab service in Singapore was the brainchild of C.F.F. Wearne and Company. Singapore became the second city in Asia after Calcutta, India, to have such a service and it was lauded as being modern and affordable. Two Rover cars were fitted with “taximeters” and were initially used to provide a reservations-only private taxi service before obtaining the licence to ply the streets for public hire. At a charge of 40 cents per mile and with a seating capacity of five passengers, taxi-cab services worked out to be no more expensive than hiring a first-class rickshaw.

A fleet of taxis along North Bridge Road, 1968. Meters were made compulsory for all licensed taxis by 1953. However, many private cars were used by unlicensed taxi drivers to ply the streets for hire. People negotiated fares with the driver and strangers could be picked up along the way to share the fare. George W. Porter Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A fleet of taxis along North Bridge Road, 1968. Meters were made compulsory for all licensed taxis by 1953. However, many private cars were used by unlicensed taxi drivers to ply the streets for hire. People negotiated fares with the driver and strangers could be picked up along the way to share the fare. George W. Porter Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

In 1919, the Singapore Motor Taxi Cab and Transport Company Limited was incorporated in the Straits Settlements (comprising Singapore, Penang and Malacca) and published its prospectus in the local newspapers to raise $350,000 as capital. The company proposed starting a taxi service comprising a fleet of 40 Ford Landaulettes as taxi-cabs. The 20-horsepower six-seater Landaulette was distributed by C.F.F. Wearne and Company.

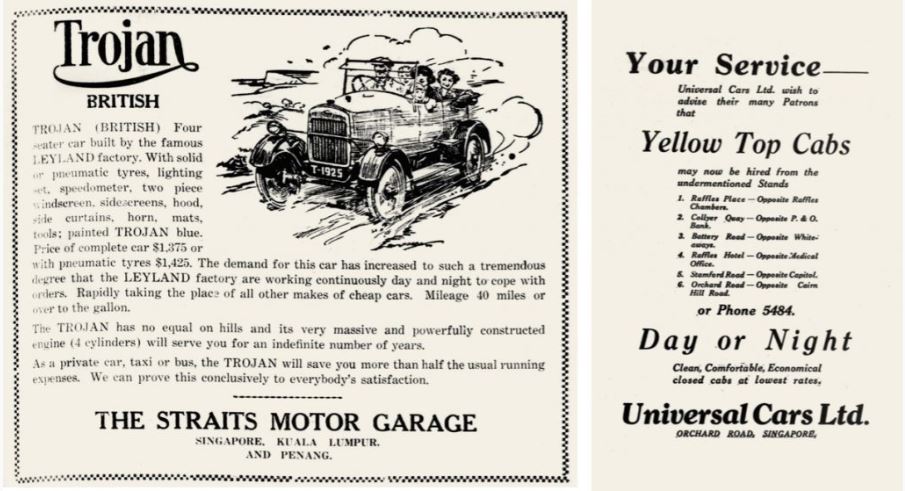

(Left) The four-seater Trojan was promoted as a “private car, taxi or bus” that could halve the usual running expenses for a car. Image reproduced from The Singapore Free Press, 9 September 1925, p. 5.

(Left) The four-seater Trojan was promoted as a “private car, taxi or bus” that could halve the usual running expenses for a car. Image reproduced from The Singapore Free Press, 9 September 1925, p. 5.(Right) Yellow Top Cabs first appeared in Singapore in 1933 and soon became a familiar sight on the streets. Image reproduced from The Straits Times, 6 November 1933, p. 16.

By the end of 1920, the Singapore Taxicab Co. was advertising a “Call a Taxi” service in *The Straits Times*. Its black-and-yellow taxis were stationed at Raffles Place, General Post Office, Grand Hotel de l’Europe, Adelphi Hotel, Raffles Hotel and the company’s garage at 1 Orchard Road, ready to pick up passengers. The fare was 40 cents per mile – the same as when taxi services were introduced a decade earlier.

Abrams’ Motor Transport Company started a vehicle-for-hire scheme in the mid-1920s. Customers could hire a car or lorry at $3 per hour, which was touted as being cheaper than a taxi. Among the car models available for hire was the five-seater Gardner.

In 1930, Borneo Motors Limited imported a new type of taximeter that could calculate fares automatically. Apparently there had been disputes between drivers and passengers over the correct fare to be paid (taximeters became compulsory only in 1953). The new taximeter had been used in other Asian cities such as Rangoon and Calcutta.

Yellow Top Cabs – launched by Universal Cars Limited which claimed to have the lowest metered rates for closed cabs – made its debut in Singapore in 1933. Advertisements for Yellow Top Cabs between 1933 and 1934 sang praises of their cleanliness, efficiency and reliability. The cabs were available at taxi stands – at Raffles Place, Collyer Quay, Battery Road, Raffles Hotel, Stamford Road and Orchard Road – and could also be booked by telephone.

After World War II, many private cars were used by unlicensed taxi drivers to ply the streets for hire. These illegal “pirate taxis” caused problems for both licensed taxi drivers as well as the authorities, although it was argued that they provided a much-needed public service.

In 1970, the National Trades Union Congress started its Comfort taxi service and offered pirate taxi drivers the opportunity to join its operations. A total ban on pirate taxis came into force in July the following year.

This essay is reproduced from the book, Between the Lines: Early Print Advertising in Singapore 1830s-1960s. Published by the National Library Board and Marshall Cavendish International Asia, it retails at major bookshops, and is also available for reference and loan at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and selected public libraries [Call nos.: RSING 659.1095957 BET].

The exhibition “Selling Dreams: Early Advertising in Singapore” takes place at level 10 of the National Library Building on Victoria Street. A variety of print advertisements from the 1830s on subjects such as food, fashion, entertainment, travel and more are on display until 24 February 2019.

Mazelan Anuar is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. His research interests are in early Singapore Malay publications and digital librarianship. He manages the National Library’s Malay language collection as well as the NewspaperSG portal. (He is a safe driver, and owns the reliable and down-to-earth Toyota Wish.)

Mazelan Anuar is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. His research interests are in early Singapore Malay publications and digital librarianship. He manages the National Library’s Malay language collection as well as the NewspaperSG portal. (He is a safe driver, and owns the reliable and down-to-earth Toyota Wish.)

NOTES

-

Definition of automobilism in English. (n.d.). English Oxford Living Dictionaries. Retrieved from Oxford University Press website. ↩

-

Singapore. Archives and Oral History Department. (1984). The land transport of Singapore: From early times to the present (p. 4). Singapore: Archives and Oral History Department; Educational Publications Bureau Pte Ltd. (Call no.: RSING 779.9388095957 LAN) ↩

-

Singapore’s first autocar. (1896, August 13). The Singapore Free Press, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Hope, T. (1935, October 8). How Singapore has been revolutionised by the modern motor car. The Singapore Free Press, p. 20; An autocar anniversary. (1927, August 13). The Singapore Free Press, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Sutton, R.T. (1958, July 5). Singapore’s first motor car was a problem. The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press, 13 Aug 1927, p. 5. ↩

-

Makepeace, W., Brooke, G.E., & Braddell, R.S.J. (Eds.). (1991). One hundred years of Singapore (Vol. 2, p. 364). Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 ONE-[HIS]) ↩

-

Davies, D. (1955, March 13). Mr. Buckley and his coffee machine. The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Groom, P. (1957, November 4). Famous ‘firsts’ of days gone by in S’pore. The Singapore Free Press, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Makepeace, Brooke, & Braddell, 1991, p. 364. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 13 Mar 1955, p. 12. ↩

-

Yap, J. (2007). Motoring beyond 100: Celebrating 100 years of the Automobile Association of Singapore (p. 15). Singapore: Automobile Association of Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 629.2830605957 YAP) ↩

-

Eckermann, E. (2001). World history of the automobile (p. 25). Warrendale, PA: Society of Automative Engineers. (Call no.: R 629.22209 ECK) ↩

-

Untitled. (1907, June 6). The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Motors & motoring. (1910, May 14). The Straits Times, p. 11; The motoring world. (1911, January 6). The Straits Times, p. 11; The motoring world. (1928, December 15). The Straits Times, p. 18. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Makepeace, Brooke, & Braddell, 1991, p. 362. ↩

-

Laird, P.W. (1996, October). “The car without a single weakness”: Early automobile advertising. Technology and Culture, 37 (4), 796–812, p. 797. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Scharchburg, R.P. (1993). Carriages without horses: J. Frank Duryea and the birth of the American automobile industry (p. 119). Warrendale, PA: Society of Automative Engineers. (Call no.: RBUS 338.7629222 SCH) ↩

-

Why buy a motor car. (1909, December 24). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Ford Company opens here. (1926, November 23). The Singapore Free Press, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Ford company in Malaya is 30 years old. (1956, November 9). The Straits Times, p. 14. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Soh, T.K. (1971, October 11). Japanese cars to cost more. The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩