Iron Spearhead: The Story of a Communist Hitman

Ronnie Tan and Goh Yu Mei recount the story of a ruthless Malayan Communist Party cadre whose cold-blooded murders caused a sensation in Singapore in the 1950s.

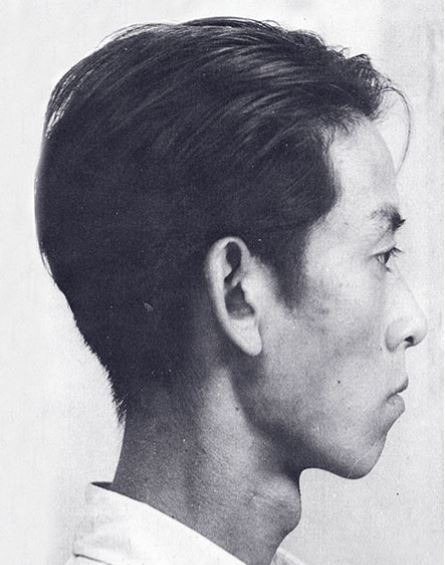

Wong Fook Kwang, who went by several aliases, including Tit Fung (literally “Iron Spearhead” in Cantonese)1 was the dreaded Commander of ‘E’ Branch, the assassination wing of the Malayan Communist Party (MCP). The MCP was most active during the Japanese Occupation years when it formed the Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA) to fight the enemy, and again in the aftermath of World War II, in the thick of the Malayan Emergency (1948–60), when it waged a guerilla war against the British in a bid to topple the colonial government and set up a communist regime.

Sometime in April 1951, Wong received a terse message from the MCP’s South Malayan Bureau’s jungle headquarters in Johor, Malaya.2 The order was clear: Lim Teck Kin, a 62-year-old “rich but kind and highly respected towkay” and pineapple magnate, must die.3 Lim was marked for assassination because he was, in the eyes of the communists, a “reactionary capitalist” employing hundreds of workers. He was therefore deemed as “an oppressor of the masses”.4

To carry out the killing, Wong ordered his henchman Yang Ah Lee5 to keep Lim under close surveillance for a week. Once the two men had established Lim’s daily routine, they put their plan into action.

Shortly after 8 am on 21 May 1951, two masked assailants intercepted Lim’s chauffeur-driven car just as it was about to leave the driveway of his house and turn onto East Coast Road. The Malay chauffeur Sairi was held at gun-point by one of the assailants, while the other fired two shots at his employer in quick succession. The deed done, the assailants walked away calmly to a waiting taxi driven by a fellow communist.

After the assailants had fled, Sairi immediately reversed the car into the driveway and raised the alarm. While one of Lim’s daughters frantically called the police, another instructed Sairi to drive her wounded father to the hospital. Lim, however, succumbed to his injuries along the way. Before losing consciousness, Lim’s last words to his chauffeur were “Apa macam?”6 or “What’s happening?” in Malay.7

Apart from masterminding Lim’s killing, Wong also instigated the murder and attempted murder of several others, including a student and even one of his comrades. Unlike in Malaya where MCP fighters could conduct open warfare from their jungle hideouts, the communists here, given that “every approach to Singapore was well-guarded”, sought to overthrow British rule “by means of subversion and terror” in order “to bring about social and industrial disruption”.8

The methods employed to achieve this included intimidation, arson attacks and murder. Wong, as the Commander of ‘E’ Branch, was tasked to carry out the killings. It was clear that he was nicknamed “Iron Spearhead” because of his cold-hearted and steely nature.

Chief Executioner of the MCP in Singapore

Little is known about Wong’s early years, except that he was born in China around 1926 and left for Singapore with his parents while still as an infant. When the Japanese invaded Singapore and Malaya during World War II, one of the first things they did was to extract revenge by singling out the Chinese for persecution, knowing that the latter had provided financial and material support for China’s war efforts against Japan. The oppressive rule of the Japanese during the Occupation years between 1942 and 1945 was exploited to the hilt by the MCP “who in the guise of patriots, enticed several thousands of young Chinese, including women, to join the MPAJA”.9 Wong was one of their most ardent recruits.

As an MPAJA member, Wong’s role was to “eradicate evils and kill traitors”.10 He was also believed to have planned the assassination of several senior Japanese officials as well as those suspected of colluding with the enemy. Wong was held in high esteem by his superiors in the MPAJA and quickly moved up the ranks. When the Emergency was declared in Malaya and Singapore in 1948, Wong, then barely 23 years old, was appointed as the MCP’s Commander of ‘E’ Branch after his predecessor left for Malaya to command a fighting unit.

The appointment obviously suited Wong to a T, for he was described as “a formidable character: ambitious, dedicated and ruthless”. He not only had a tight grip on the unit’s finances, his word too was law, for in meetings he was “always in the chair, directing and giving orders”.11 It was at one of those meetings that businessman Lim Teck Kin’s fate was sealed as well as that other victims – including the failed attempt on the life of a 14-year-old student.

How to Murder a Teen

Upon receiving instructions from the MCP’s South Malayan Bureau’s headquarters to take out an unnamed 14-year-old male student – who was suspected to have provided leads to the police about an acid attack on a teacher – Wong took a personal interest in planning the murder. The heinous attack on the teacher was believed to have been carried out by his own pupils.12 Just as he had planned the earlier murder of Lim Teck Kin, Wong monitored the student’s movements and ambushed the teen while he was cycling home after a game.

On 2 October 1951, the plan was put into action. With Wong watching expectantly from behind an inconspicuous doorway, two of his assailants, one of whom acted as a look-out, waited for the student to cycle past River Valley Road. However, unlike other days, this time the boy was not alone. He had met a friend earlier and decided to dismount his bicycle and walk with his friend along the pavement while pushing his bicycle.

At the junction of Teck Guan Road and River Valley Road, one of Wong’s accomplices suddenly emerged from his hiding place and took the boys by surprise. Pulling out his gun, he fired six shots at the intended victim at point blank. Miraculously, the bullets missed their target and the boy managed to make a run for it. Incredibly, there were no passers-by nor motorists to witness the attempted murder along the busy road, so even the police were not notified immediately. By the time the boy managed to compose himself and make a police report, a few hours had lapsed, by which time Wong and his accomplices had long made their getaway in a trishaw.

While fleeing from the scene, Wong and the gunman had a close call: the trishaw they were travelling in was stopped by a police car on routine patrol. Fortunately for the two men, the police officers had no inkling of the botched attempt to kill the boy and only did an identity card check. Had they carried out a full body search, the outcome for Wong and his accomplice would have been very different as the weapon used in the attempted murder was still in the gunman’s possession.

How to Murder a Comrade

Even before the attempted murder of the student, Wong had ordered and planned the murder of one of his own comrades, a 30-year-old man named Siu Moh. Siu was suspected by his superior Ah Poh of embezzling $300 – money that had been extorted from various businessmen and shopkeepers. Wong concurred with Ah Poh that Siu must pay for his alleged misdeeds with his life.

Kong Lee,13 a member of the ‘E’ Branch Committee, however, disagreed with the plan to kill Siu and made his view known to Wong. The latter paid no heed to this and was prepared to contravene party rules, which made it clear that no one was to kill a fellow communist without the express approval of the MCP headquarters in Johor. So Wong decided to carry out his task quietly, seeing to it that Siu “would simply disappear forever”.14 To this end, both he and Ah Poh hatched a meticulous plan to kill Siu and dispose of his remains secretly. They decided that after the murder, Siu’s remains would be buried in a prawn pond in a tidal swamp at the end of Upper Serangoon Road.

On 1 September 1951, Siu was lured to a desolate hut rented from a shrimp catcher. Here, he faced a kangaroo court, with Wong acting as both accuser and judge. During the mock trial, Wong accused Siu of embezzlement, despite the latter’s denials. Wong’s co-accusers at the clandestine gathering included Ah Poh, a lady named Lim Wai Yin (alias Ah Soo) and two other unnamed accomplices. Siu’s protestations were ignored. His accusers bound him hand and foot, gagged him with a cloth, bundled him into a boat and rowed out to a site nearby where he was mercilessly hacked to death. After the deed was done, Wong “swore his followers to secrecy – on pain of death”.15

Capture and Detention

On 11 June 1952, four policemen, including a Chinese lieutenant, were in a police car patrolling the area around Bugis and Rochor roads. At 1.10 pm, they turned onto Albert Street, which was “renowned for good, inexpensive, Chinese food”,16 with the intention of conducting surprise checks at coffee shops in the area. The police officers approached a table with three Chinese men, who were so engrossed in eating and drinking that they did not notice them.

When asked to produce their identity cards, all three men refused to do so. The police lieutenant then raised his voice, to which the men reluctantly complied. Unbeknownst to the police officers, one of the men in the group was the villainous Wong Fook Kwang. An unsuspecting police corporal turned to Wong and did a body search for weapons, finding on his person instead a paper packet containing what appeared to be dried plums. Still suspicious, the corporal separated the fruit from the paper. In that instant, Wong bolted from the coffee shop and into a side street leading to Rochor Road, with the police officers hot on his heels.

At the height of the chase, a young Englishman happened to be driving along Rochor Road. On seeing a Chinese man being pursued by the police, he decided to join the chase, stepping on the accelerator to catch up with the fleeing suspect. The Englishman managed to knock Wong down with the fender of his car and got out to apprehend him until the pursuing policemen arrived. A search of the suspect’s pockets unearthed several Chinese newspaper cuttings relating to communist activities. An examination of his identity card revealed that he was Wong Fook Kwang – a name that did not mean anything to the police officers at the time.

Wong’s name did not show up on the wanted list because the police were blissfully unaware of his identity as the commander of the MCP’s assassination wing in Singapore. As author Peter Claque put it, “The police lieutenant was like a man who shoots at a noise in the jungle hoping to kill a pigeon and discovers that he has shot a tiger”.17 In the meantime, the other two men who had been with Wong had already made their escape by the time the policemen returned to the coffee shop.

Wong was taken to Beach Road Police Station where Special Branch officers were waiting to question him and examine the newspaper cuttings. True to his nature, Wong remained silent18 when he was interrogated by Special Branch officer, Superintendent John Fairbairn.19 A police search of the house located at the address listed in Wong’s identity card unearthed a cache of communist literature and documents, evidence which proved that Wong “had important communist connections and was a leader of some kind”.20

On 27 June 1952, Wong was ordered to be detained under the Emergency Regulations21 for two years. Shortly after his arrest, Wong was visited by an elderly Chinese lady who claimed to be his mother.22 She said that Wong was her only son, and appealed to the authorities for his release but to no avail. The Special Branch came down hard on anyone deemed to have communist connections.

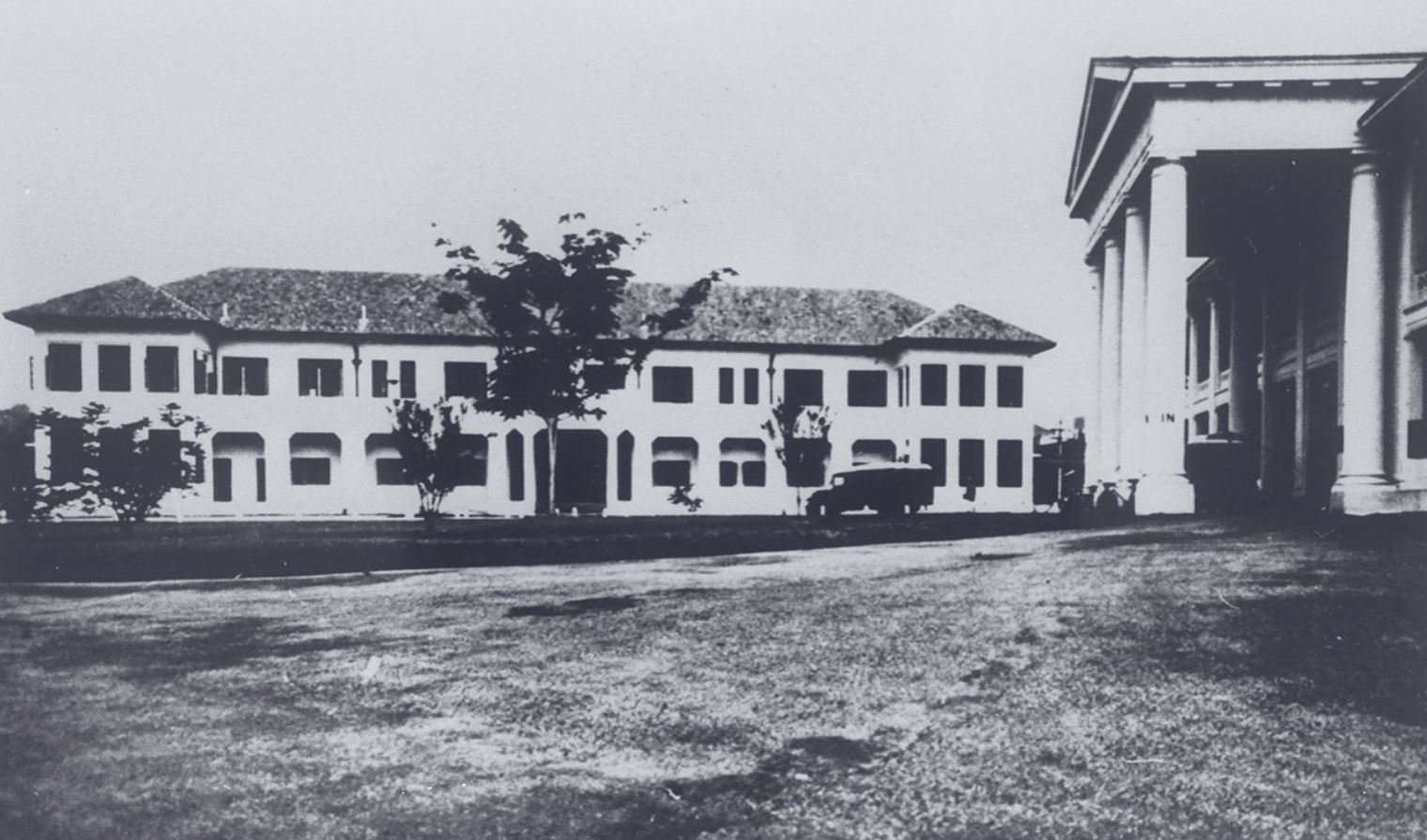

The day after his arrest, Wong appeared ill and a doctor confirmed that he was suffering from advanced tuberculosis and had to be moved to the prison ward at the Singapore General Hospital (SGH) for observation and treatment. When doctors assessed that Wong had recovered sufficiently, he was transferred back to Changi Prison on 16 October 1952 and placed in solitary confinement. Twelve weeks later, on 15 January 1953, Wong suffered a relapse and was sent back to the prison ward for treatment. His condition had deteriorated to the point that it was presumed his end was near. But somehow he survived.

During Wong’s second stay in hospital, the elderly woman who had earlier claimed to be his mother visited him several times. On one of her visits, she was accompanied by a man (later found to be a member of the MCP who had taken the opportunity to survey the surroundings). The information was likely used to plan Wong’s escape after MCP leaders had sanctioned it.23

On 4 March 1953, between 2 and 4 pm, the elderly woman again visited Wong at the prison ward. She also brought him a parcel of food. The parcel was thoroughly examined by a senior guard on duty before she was allowed entry. After being let through, Wong’s “mother” spoke to him in hushed tones – likely informing him of the impending attempt to help him escape.

The Brazen Escape

A severe thunderstorm raged that night. At 9.30 pm, the nurse on duty visited the 12 patients in the prison ward and noticed that Wong was in bed but awake. Shortly after, the duty police corporal switched off the lights and the nurse’s assistant went round the ward to place the last dose of medication for the day on the patients’ bedside tables. When the assistant reached Wong’s empty bed, he assumed that Wong had gone to the bathroom, so he put the medicine on the table and moved on.

Unbeknownst to him, Wong had made a run for it earlier, barefooted and in his hospital pyjamas. How he had pulled off this brazen prison break “without being seen by the three constables who guarded the ward” is a mystery to this day. The 1.7-metre-tall fugitive managed to escape with the help of a man named Ah Hong, who had sawn through the wire netting that covered most of the window of his cell as well as the inch-thick iron bars, bending it outwards in the process. “While the sawing was going on, Wong hid quietly in the verandah. He had managed to slip out of his bed unnoticed.”24

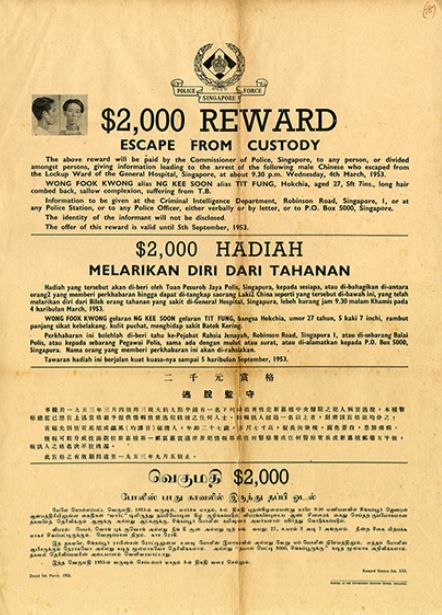

The alarm was raised at 9.40 pm when a sentry doing his rounds discovered the sawn iron bar. Special Branch was immediately alerted and road blocks set up islandwide to recapture Wong. A bounty of $2,000 was offered for information leading to his recapture. Sometime close to midnight, the hacksaw used to commit the mischief was discovered nearby. The four guards were suspended for being negligent in their duty and subsequently sacked.

Wong had escaped without his identity card as it was kept in a safe by Fairbairn. Since it was not possible for Wong to move around Singapore freely without one, especially with police road blocks set up in densely populated areas, Fairbairn knew that Wong would most likely seek refuge in rural suburbs where it would be easier to hide. The search for Wong, however, turned out to be a protracted affair that took more than a year.

Fairbairn’s hunch was right; after Wong had successfully evaded the police dragnet, he found his way to Pasir Laba25 in Jurong, in the western part of the island. There, for more than a year, he posed as a farmer and lived in an “attap-roofed shack, surrounded by lallang and bushes” in a low-lying, swampy area.26 During his time on the run, Wong had recovered fully from tuberculosis, dosing himself on controlled drugs smuggled into Singapore by fellow communists in Johor.

Wong’s Recapture

It was in October 1953, seven months after the brazen escape in March, that Special Branch received a tip-off from underworld sources that Wong was hiding out “in a small hut in a patch of jungle on Singapore Island, about 200 yards from an unnamed village north-west of the city”.27 They were also informed that Wong was protected by two armed men at all times.

It would take another nine months before Wong would be nabbed. Special Branch officers devised a meticulous plan. It initially involved gathering intelligence on the terrain and inhabitants in the area. Later, the officers discovered that there were many stray dogs in the area that were likely to bark at approaching strangers and alert Wong. It was clear that the best way to recapture Wong was to have policemen encircle the entire area surrounding the hideout.

Fairbairn also requested for Royal Air Force reconnaissance planes to fly over the area at irregular intervals to obtain aerial photographs. After carefully studying the images, Fairbairn concluded that he would need some 300 men for the job. Fortunately, he had the support of Alan Blades, Head of Special Branch, for the massive operation.

Shortly after midnight on 9 July 1954, a police convoy travelled along Jurong Road towards Pasir Laba. Soon, the entire area was completely surrounded by police officers. At 8.40 am, they barged into Wong’s shack but found that it had already been evacuated. Wong had managed to escape again!

A thorough search was made of the surroundings to flush out the fugitive. This time Wong did not get very far: he was found lying face down in the lallang, hoping that the tall grass would shield him, when a policeman nearly stepped on him. Wong did not put up a struggle, and was handcuffed and brought before Fairbairn. In Wong’s makeshift dwelling, the police found the drugs he had been using to treat his tuberculosis as well as banned communist publications. He had apparently made a full recovery by the time he was caught.

Postscript

At Wong’s trial in November 1954, his one-time comrades, Kuan Kay Tee and Yang Ah Lee, both of whom had defected, spilled the beans on him. They revealed details of the events leading up to Siu Moh’s murder, the whereabouts of Siu’s remains as well as Wong’s role in Lim Teck Kin’s murder. Despite their testimonies against him in court, Wong was not convicted of murder due to insufficient evidence. He was sentenced to a three-month jail term for escaping from prison, in addition to another five years for possessing banned communist literature. Even so, the punishment meted out to Wong seems light given the severity of his crime. During his trial, Wong asked to be banished to China with his mother instead of a prison sentence. It would take two years before his wish was granted on 20 June 1956.

Sometime in 1953, Wong had become engaged to Lin Hui Ying (林惠英), a fellow MCP member.28 Shortly after their marriage was approved by the MCP, she was arrested for her communist work.29 In 1954, Lin gave birth to their daughter in prison, and upon her release in 1955, she was deported to China. She settled in Hainan island and Wong subsequently lost contact with her.

In China, Wong married another woman. Although the union resulted in the birth of a son and daughter, it did not last and the couple were divorced in 1980. Wong then began searching for Lin.30 Unfortunately, by the time Wong received news of her in early 2004, she had already passed away the year before on 14 February 2003 at the age of 89. Wong died three years later in a hospital in Fuqing, in the city of Fuzhou.31

Ronnie Tan is a Senior Manager (Research) with the National Library, Singapore, where he conducts research on public policy as well as historical, regional and library-related issues. His other research interests include Malayan history, especially the Malayan Emergency (1948-60), and military history.

Ronnie Tan is a Senior Manager (Research) with the National Library, Singapore, where he conducts research on public policy as well as historical, regional and library-related issues. His other research interests include Malayan history, especially the Malayan Emergency (1948-60), and military history.

Goh Yu Mei is a Librarian with the National Library, Singapore, where she manages the Chinese arts and literature collection. She is interested in the relationship between society and literature.

Goh Yu Mei is a Librarian with the National Library, Singapore, where she manages the Chinese arts and literature collection. She is interested in the relationship between society and literature.

Notes

-

Wong’s last name is spelled “Kwang” in Peter Claque’s book and The Straits Times, while it is spelled “Kwong” in the Singapore Standard. Wong was also known by aliases such as Tit Fung (also spelled as “Thit Fong”) and Ng Hock Kwan. Although Tit Fung is Cantonese, which was Wong’s spoken dialect, his actual dialect group is Foochow. It is not known when Iron Spearhead was added to his string of aliases. ↩

-

Singh, B. (2015). Quest for political power: Communist subversion and militancy in Singapore (p. xxv). Singapore: Marshall Cavendish International. (Call no.: RSING 335.4095957 SIN) ↩

-

Toh, W.C., & Clague, P. (1980, August 2). Story that’s woven around a pistol and a Red. The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Clague, P. (1980). Iron Spearhead: The true story of a communist killer squad in Singapore (p. 3). Singapore: Heinemann Educational Books (Asia) Ltd. (Call no.: RSING 335.43095957 CLA) ↩

-

Yang Ah Lee would later defect to the British and work for the Criminal Investigation Department. He also testified against Wong during the latter’s trial for Siu Moh’s murder. ↩

-

Masked youth shoots millionare. (1951, May 22). Singapore Standard. p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Hsiaoshuang. (1980, July 12). First class thriller material. New Nation, p. 15. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

彭国强. (主编). [Peng, G. Q. (Ed.).] (2005). 激情岁月 [Fervid Times] (p. 107). 香港: 香港见证出版社. (Not in NLB holdings) ↩

-

In those days, the communists infiltrated and subverted Chinese schools to rally the students to their cause. ↩

-

Kong Lee is the alias of Kuan Kay Tee who, like Yang Ah Lee, later defected and joined the police force as a detective corporal attached to the Special Branch of the Criminal Investigation Department. Kuan also testified against Wong at his trial for Siu Moh’s murder. ↩

-

Throughout his time under police custody, Wong pretended to cooperate with the police but Special Branch officers knew that he was lying. The only crime he admitted to was his unsuccessful attempt to burn down a bus. Wong was eventually charged with the possession of communist publications. ↩

-

This is the same John Fairbairn who conducted a joint operation with his Malayan counterparts to arrest Ah Shu, a communist courier, in Singapore in 1952, and uncovered a trail that eventually resulted in the arrest of Lee Meng, the head courier of the MCP. For more information, see Tan, R. (2018, April–June). Hunting down the Malayan Mata Hari. BiblioAsia, 14(1), 24–29. Retrieved from BiblioAsia website. ↩

-

For more information on the Emergency Regulations, see Renick, R. (1965, September). The Emergency regulations of Malaya causes and effect. Journal of Southeast Asian History, 6(2), 1–39. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

After the elderly lady was arrested shortly after Wong’s escape, it was revealed that she was a communist agent. However, in an article published in 2005, Wong confirmed that the elderly woman was indeed his mother. See 彭国强, 2005, pp. 115–116. ↩

-

彭国强, 2005, p. 115. ↩

-

Police arrest mother after red thug leader escapes. (1953, March 6). The Straits Times, p. 1; Daring escape of red arson expert. (1953, March 8). Singapore Standard, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

On 14 February 1966, the area around Pasir Laba became a military training ground with the establishment of the Singapore Armed Forces Training Institute (SAFTI). ↩

-

Peries, B. (1954, July 11). ‘Iron Spearhead’ posed as a farmer. Singapore Standard, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Lin Hui Ying adopted another name, Lin Fei Yan (林飞燕), after she was banished to China. See 张惠宁和潘正悦. [Zhang, H.N. & Pan, Z.Y.]. (2004, January 20). 八旬老人欲寻当年 “红色恋人”[80-year-old elderly hopes to find his “red lover”]. 海南日报. Retrieved from Sina website. ↩

-

According to Leon Comber, however, Ah Soo (the alias of Lim Wai Yin), who was arrested in early 1952 for communist activities, was Wong’s wife. See Comber, L. (2008). Malaya’s secret police 1945–60: The role of the Special Branch in the Malayan Emergency (p. 229). Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies; Australia: Monash Asia Institute. (Call no:. RSING 363.283095951 COM) ↩

-

张惠宁和潘正悦, 20 Jan 2004. ↩

-

张惠宁和潘正悦. [Zhang, H.N. & Pan, Z.Y.]. (2004, February 3). 伊人已逝:此情只可成追忆 [She has passed on and the love has turned to a memory]. 海南日报. Retrieved from Sina website. ↩