When There Were Farms

Zoe Yeo presents a selection of publications on farming in Singapore from the National Library’s Legal Deposit Collection.

Food supplies imported from the far corners of the world catering to the taste buds of Singapore’s diverse races have always been readily available on the island. Although agriculture has never been a major pillar in Singapore’s economy given the scarcity of land, the city-state has sought to be self-sufficient when it comes to food. This was especially the case in the years following World War II.

During the Japanese Occupation (1942–45), people endured untold hardship and hunger when the main sources of food were cut off abruptly. As there was not enough food to go around, a black market quickly developed with prices hiked up to exorbitant levels. Left with little choice and unable to survive on food rations alone, many people resorted to growing their own food, such as tapioca, sweet potato, vegetables and the like, to stave off hunger during the war years.

In the aftermath of the war, extensive efforts were made to increase Singapore’s food production, particularly with regard to vegetables and livestock such as pigs, poultry, cattle, sheep and goats. In fact, the poultry industry developed so rapidly that Singapore became self-sufficient and was able to export the excess to neighbouring countries within a few years after the war.1 In 1948, the Department of Agriculture released the first comprehensive report on farming on the island, recording a three-fold increase in the area set aside for the cultivation of miscellaneous crops – from 5,202 acres in 1940 to 15,300 acres by 1947.

A School for Farmers

On 25 June 1959, barely a month after the People’s Action Party won the elections, the government announced the amalgamation of the agriculture, co-operatives, fisheries, rural development and veterinary divisions of the Ministry of National Development into the Primary Production Department (PPD).

The main objective of the new department was to ensure that the needs of farmers and fishermen were better served, and to facilitate cooperation between various units so that policies could be implemented more quickly. One area of priority was the improvement of production by introducing new methods of farming and fishing.2

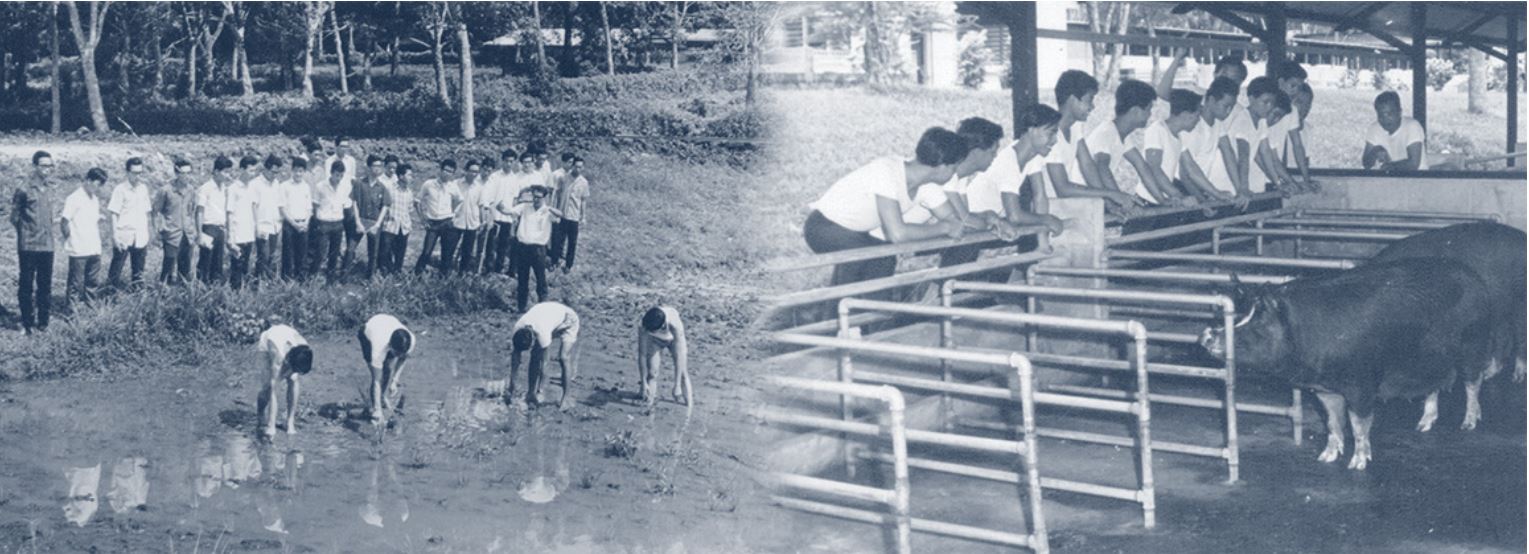

The Farm School at Sembawang – the first of its kind in Singapore – commenced classes on 1 August 1965. The school aimed to boost the agricultural output of the state with a programme that would equip novice farmers and fishermen with practical and technical farming skills.

Built at a cost of $250,000, the school – located in the Central Research Station of the PPD office on Sembawang Road – was a joint effort by the Ministry of National Development and the Ministry of Education.

To qualify for the farming programme, applicants were required to have at least primary six qualifications and be a full-time farmer. If the applicant was not a farmer, then the person’s guardian should be one. School fees were waived and, instead, trainees received a monthly allowance of $100 from the government, of which $65 was deducted for food and lodging.

After training more than 20 batches of students, the school announced its closure in November 1984 due to dwindling enrolment – marking the end of the first and only school dedicated to farming in Singapore.3

High-tech Farming

Over the decades, rapid urbanisation has greatly reduced land available for farming in Singapore, from 32,069 acres in 1966 to a mere 3,620 acres today. Farming activities are presently concentrated at six agrotechnology parks located in low density areas such as Lim Chu Kang, Murai, Sungei Tengah, Nee Soon, Mandai and Loyang.

These parks optimise the use of the island’s limited land space by increasing productivity through the application of science and technology in farming methods. Apart from food production, farms located in agrotechnology parks also serve as research and development hubs, and have developed innovative and creative farming methods suited for the tropics.

Additionally, these farms have transformed their traditional business models by tapping the eco-tourism market and offering “agri-tainment” to visitors. Today, people who visit agrotechnology parks can participate in activities such as goat milking, learning about frog farming and even opting for a farm-stay to be up close and personal with nature.4

Here is a sampling of publications on farms and farming from the National Library’s Legal Deposit Collection.

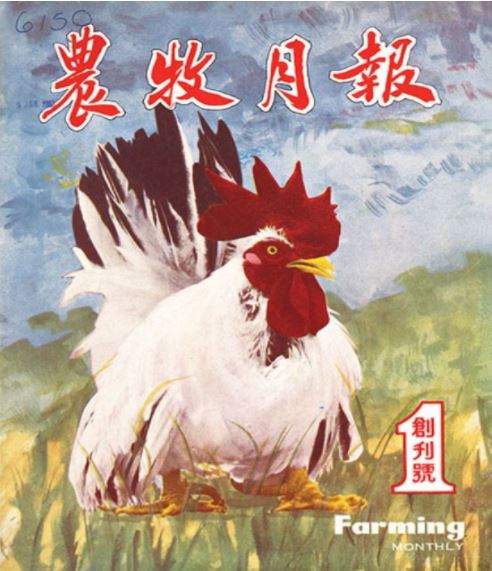

This publication was started by pioneering poultry farmer Ho Seng Choon, with the aim of keeping farmers in Singapore and Malaya updated on the latest information and technology on poultry farming. Ho’s farm, Lian Wah Hang Quail and Poultry Farm, is one of the oldest surviving farms in Singapore today. This inaugural issue, published in August 1962, covers subjects such as best practices in poultry farming and the challenges encountered in the rearing of domesticated birds.

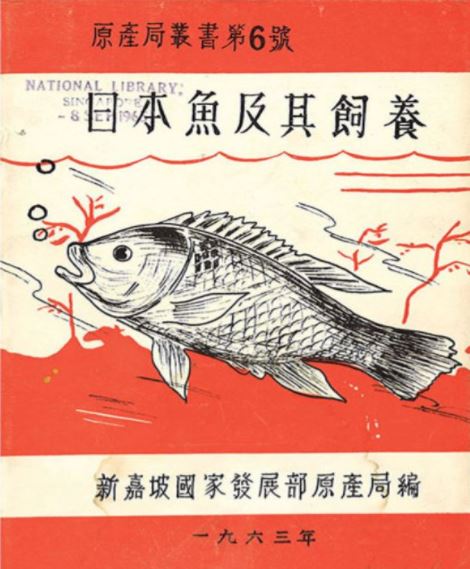

Varieties of Japanese fish were first introduced to Singapore during the Japanese Occupation as a substitute for the falling number of local saltwater fish and carps, whose import from China was restricted during the war. Known for their tenacity and ability to adapt to both fresh and salt water, Japanese breeds grew to become one of the most commonly reared fish in Singapore in the 1960s.

The life of a trainee at the Farm School is depicted through photos in this booklet produced by the Primary Production Department. Trainees started their day with practical farming work in the morning and attended lectures in the afternoon. The school also organised film shows and tours to feedmills, private farms, factories and places of interest. Additionally, well-known personalities in the farming industry were invited to give talks on farming and other related topics.

Goat farms in 1960s Singapore reared goats ranging from local species to breeds imported from Switzerland and India. Booklets published by the Primary Production Department provided farmers with tips on taking care of different types of goats, including breeding methods, feeding and the proper ways of housing the goats.

Legal Deposit is one of the statutory functions of the National Library and is supported through the provisions of the National Library Board Act. Under the act, all publishers, commercial or otherwise, are required by law to deposit two copies of every physical work and one copy of every electronic work published in Singapore, for sale or public distribution, with the National Library within four weeks of its publication. The Legal Deposit function ensures that a repository of Singapore’s published heritage is preserved for future generations. For more information, please visit www.nlb.gov.sg/Deposit.

Zoe Yeo is an Associate Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. Her responsibilities include developing the National Library’s collections as well as providing content and reference services on topics relating to Singapore and Southeast Asia.

Zoe Yeo is an Associate Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. Her responsibilities include developing the National Library’s collections as well as providing content and reference services on topics relating to Singapore and Southeast Asia.

NOTES

-

Malayan Agri-Horticultural Association. (1956). The First Singapore Agricultural Show, 1–5 September, 1956; Souvenir Programme. Singapore: Public Relations Office. (Call no.: RDTYS 630.95951 MAL) ↩

-

National Library Board. (2014). Primary Production Department is formed. Retrieved from National Library Online. ↩

-

农业学校停办, (1984, November 29). 联合早报 (Lianhe Zaobao), p. 5.Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

National Library Board. (2009). Farmlands in Lim Chu Kang written by Jean Lim. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia. ↩