Wartime Victuals: Surviving the Japanese Occupation

Desperate times call for desperate measures. Lee Geok Boi trawls the oral history collection of the National Archives to document how people coped with the precious little food they had during the war.

A father and daughter having a simple meal of porridge and nuts. Deprivation and hardship were a constant feature of life during the Japanese Occupation. Image reproduced from Wikimedia Commons.

A father and daughter having a simple meal of porridge and nuts. Deprivation and hardship were a constant feature of life during the Japanese Occupation. Image reproduced from Wikimedia Commons.In times of war and occupation, food is about survival and not quality or flavour. For the people who lived through Singapore’s harrowing Japanese Occupation years from 1942 to 1945, survival was made all the more difficult for a number of reasons.

Singapore has always been a port city, its lifeline fuelled by trade and commerce.1 Although the first commercial plantations of nutmeg and pepper never quite took off,2 there were considerable swathes of land where pineapple, coconut and rubber grew in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

The town centre made up less than a quarter of the island and there were plenty of rural areas with kampongs that were engaged in market gardening, poultry and pig rearing,3 along with Indian dairy farmers who kept cows to produce milk for sale. Singapore’s rural areas were, in fact, so large that the Municipal Council that administered the island had a Rural Board.

The 1931 census put the population of Singapore at 557,7004 (although a census had been planned for 1941, it was never carried out because of the war). The only pre-war figure available is a 1939 estimation by the British, who cited the population size as 767,700.5 In 1943, the Chosabu (Department of Research),6 estimated that the population in Syonan-to – the Japanese name for occupied Singapore (meaning “Light of the South Island”) – was around 900,000.7

The sudden spike in the population between 1939 and 1943 arose from the influx of refugees from Malaya in search of safety on the island as well as the injection of some 100,000 British Army troops into Singapore for the defence of British Malaya.8 The unexpected increase in the population put severe pressure on food supplies, which was not a good thing as Singapore imported most of its food.

Pre-war Singapore was the key port in the region, handling not only commodities such as tin, rubber and copra (dried coconut kernels from which oil is obtained) from Malaya, but also the storage and distribution of oil from the Dutch East Indies (present-day Indonesia) and Borneo. Singapore was also a major distribution centre for foodstuffs and consumer goods in the region, with Japan as a key trading partner. In the 1930s, Japan supplied more than half of Singapore’s everyday essentials, ranging from canned sardines and cotton goods to glassware and bicycles.9

Once Japan’s economy went on a war footing, it ceased to be Malaya’s main source of consumer goods. At the same time, Singapore’s other supply chains were affected by the war in Europe. More critically, Japan’s Pacific War disrupted Singapore’s food supply. Train and shipping lines that used to transport rice from Burma and Thailand were seized by the military, and the movement of people and goods were subjected to strict security checks. At the same time, traditional rice-growing cycles were affected by the war, leading to a reduced supply at a time when the need was greatest.

Pre-war Singapore hosted small enterprises producing such foodstuffs as soya sauce, noodles, tofu (beancurd), bread, biscuits and confectionery, all of which depended on imported ingredients. Once the supply of basic imported ingredients were cut off, these businesses either had to close down or resort to using substitutes.

For example, noodle makers had to use tapioca flour as a substitute for wheat or rice flour. People had to adjust their eating habits, switching from rice to other more easily available carbohydrates such as tapioca and sweet potatoes. While Singapore did not face outright famine during the Occupation years, it saw an increase in diseases relating to malnutrition and a spike in deaths. Between 1942 and 1945, the combined death rate for men and women more than doubled from 29,831 to 65,158.10

Queuing Up for Food

At the start of the Occupation in 1942, the Japanese seized the food stocks that had been set aside by the British. The appropriated stockpiles were reserved for Japanese military use with a smaller portion set aside for the general population.

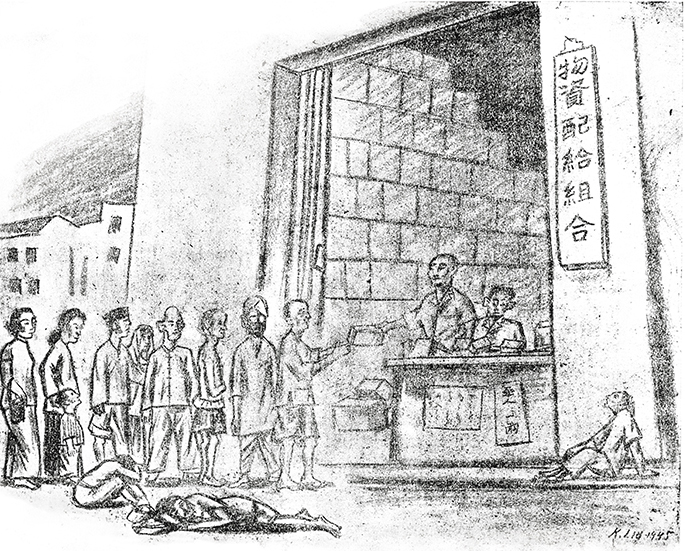

This sketch by the artist Liu Kang portrays the Japanese distribution system of essentials, which was widely seen as responsible for the black market, and the enrichment of the Japanese and unscrupulous businessmen. Image reproduced from Liu, K. (1946). Chop Suey (Vol. I). Singapore: Eastern Art Co. Collection of the National Library Singapore (Accession no.: B02901746G).

This sketch by the artist Liu Kang portrays the Japanese distribution system of essentials, which was widely seen as responsible for the black market, and the enrichment of the Japanese and unscrupulous businessmen. Image reproduced from Liu, K. (1946). Chop Suey (Vol. I). Singapore: Eastern Art Co. Collection of the National Library Singapore (Accession no.: B02901746G).The British defence strategy for Singapore in the face of an impending crisis was to hold out until naval ships came to the rescue. Part of this defence plan involved the stockpiling of food until help came, but this was never fully realised as Singapore’s humid climate meant that food supplies could not be stored for long periods. In any case, in the final days preceding the fall of Singapore, warehouses and shops were looted. Immediately after the British surrendered, Japanese soldiers conducted house-to-house searches; if loot was discovered, it was confiscated, and the perpetrators had their heads promptly cut off.

Food import and export businesses in Singapore were taken over by Japanese companies, and the military administration began grouping suppliers of various commodities into distribution monopolies called kumiai. For instance, the import and distribution of rice was handled by Mitsubishi Shoji Corporation. The Cold Storage supermarket, which had a good refrigeration system and was a major importer of frozen meat, was made into a butai, a company linked to the military.

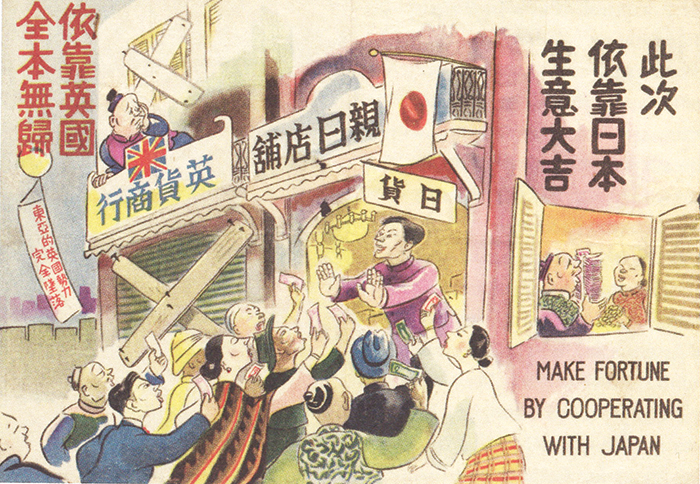

During the Japanese Occupation, food import and export businesses in Singapore were taken over by Japanese companies. This is a propaganda leaflet promoting Japanese goods and cooperation with the Japanese. Source: David Ernest Srinivasagam Chelliah (Acc 4/1990, 18).

During the Japanese Occupation, food import and export businesses in Singapore were taken over by Japanese companies. This is a propaganda leaflet promoting Japanese goods and cooperation with the Japanese. Source: David Ernest Srinivasagam Chelliah (Acc 4/1990, 18).To exercise control over the population and the supply of food, a rationing system was instituted and the members of all households had to be registered to receive ration cards. As part of the rationing system, any movement of people from one household to another or out of Singapore had to be reported to the neighbourhood police. Rations would then be adjusted accordingly. Food and other related essentials were sold at controlled prices that were published in the newspapers daily. Theoretically, consumers could buy their rations at fixed prices although in practice, this was not the case.

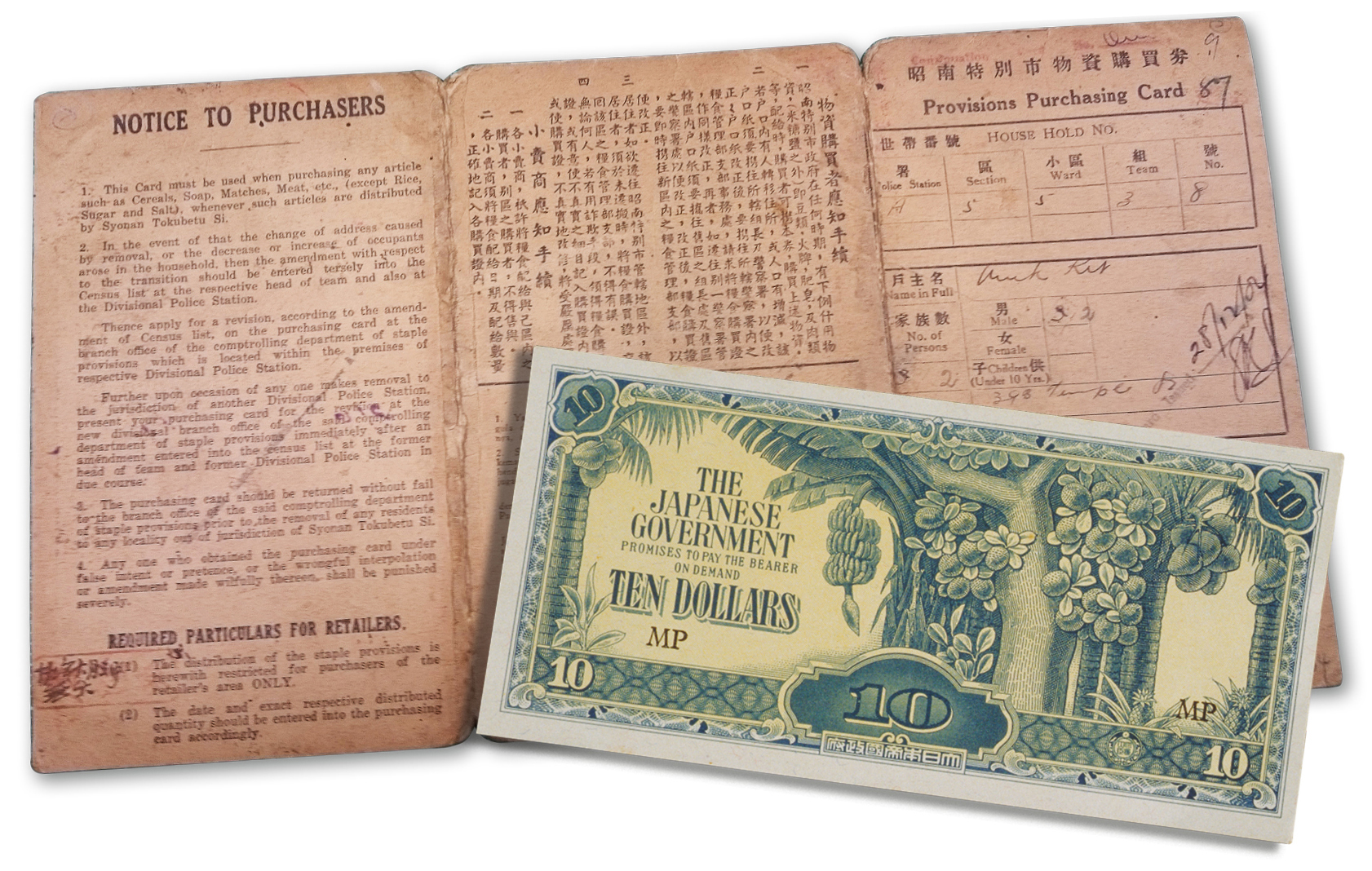

(Top) A provisions purchasing card issued to households during the Japanese Occupation for the purchase of items such as cereal, soap, matches, meat, etc. (except rice, sugar and salt) distributed by the Syonan Tokubetsu Si (Municipal Administration). Mak Kit Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

(Top) A provisions purchasing card issued to households during the Japanese Occupation for the purchase of items such as cereal, soap, matches, meat, etc. (except rice, sugar and salt) distributed by the Syonan Tokubetsu Si (Municipal Administration). Mak Kit Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore. (Bottom) A $10 bill in use during the Japanese Occupation. Known as “banana money” because of the motifs of banana trees on the bank notes, the currency became worthless due to runaway inflation coupled with black market practices. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

Long queues for rations would form hours before the shops opened and people were rarely able to buy their quota of foodstuffs at the published prices. The quality, too, left much to be desired: rice was often weevil-infested and the sugar damp.

Over time, the rations shrank in quantity as well. The rice ration, for instance, started at 20 katis (about 12 kg) a month per person, dropping to 8 katis for men, 6 katis for women and 4 katis per child towards the end of the Occupation. Even then, people were not allowed to buy the full month’s entitlement all at once, but had to queue for them weekly or whenever new supplies were available.

Food became “cash” in the war economy. It became the practice for big companies to provide lunch for the staff as part of their wages. Cold Storage, being a butai, appeared to have been particularly generous in this regard. Chinese primary school teacher Tan Cheng Hwee, who used to work for Cold Storage during the Japanese Occupation, remembered his very big lunches at work:

“That is the best part of our lives in Cold Storage, because our lunch, I think, is equivalent to that of the Commander-in-Chief of this Japanese Army in Singapore. Every day on each table, we had one [imported from the US] Rhode Island chicken. And we can pick and choose whatever liver we want. We had four plates and one cup of soup. And each bowl of vegetables is a very big one. We had so much to eat. So much so – there were about 20 people eating at the Cold Storage – every day they had enough remaining for eight people to carry home.”11

On top of this generous lunch, Tan was given 1 kg of rice to take home every day. Bags of rice became prizes at competitive games and social functions as well as wages for work done. It was more valuable than “banana money”,12 the currency introduced by the Japanese for use in the Japan-occupied territories of Singapore, Malaya, North Borneo, Sarawak and Brunei.

Another form of “cash” were the vouchers that were given out for various things; especially valuable were vouchers for cloth and clothing. Couples who registered with the military government their intent to marry were given cloth vouchers that could be exchanged or sold for something else. Informal barter trade became common. If someone had harvested too much tapioca, he could exchange it with a friend or neighbour for sweet potatoes or vegetables.

Given the shortages, celebrations of annual festivals and weddings were invariably low key. In any case, the Japanese military police, or Kempeitai, frowned on large gatherings and imposed a nightly curfew. Celebratory meals, on the rare occasions that they took place, were usually lunches and it was not uncommon for guests to bring food to share at the table.

Black Market Blues

Defined as the “illegal trading of goods that are not allowed to be bought and sold, of which there are not enough of for everyone who wants them”, the black market was very active during the Occupation years. Scarcity led to hoarding and inflated prices even though hoarding was a crime. Corrupt officials in the monopolies set up by the Syonan administration were themselves responsible for hoarding and trading on the black market for personal gain.

Many people who survived the Occupation had no choice but to turn to the black market for much sought-after medicines, tinned milk for babies and better food for the sick, among other goods. The black market was the only recourse as people began to release their hoarded stockpiles in order to get their hands on other essentials they needed.

Although British propaganda was remarkably effective in persuading people that the outbreak of World War II in Europe in 1939 would not reach Singapore, the more far-sighted had begun hoarding essentials to see themselves through what could be a really difficult time.

The relatively wealthier segments of Asian society in pre-war Singapore accumulated assets such as gold, jewellery, household goods, furniture and clothes. Some converted fixed assets such as property or land into gold or Straits dollars, which they kept hidden until the need to use them arose. As existing stocks of essential goods in occupied Singapore depleted and shortages were more acutely felt, all manner of consumer goods surfaced in the black market.

As the Japanese administration printed more “banana money” to fund its war expenses, the value of the notes plummeted in value, made all the worse by the rise of counterfeit money. Spiralling prices meant that one had to carry large bags of notes just to buy the smallest items. Businessman Chua Eng Cheow said that when the banana notes were first introduced, the value was on par with the Straits dollar. Pre-war an egg cost 3 cents, but at the end the Occupation it was $100. A kati (600 g) of pork went from 30 cents to $1,500!13 The Straits dollar, gold and jewellery re-surfaced on the black market in lieu of the “banana” currency.

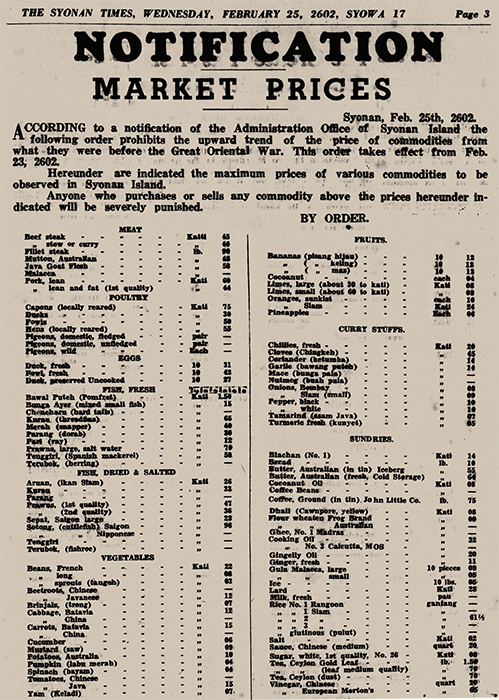

A newspaper notice listing the prices of basic food items at the start of the Japanese Occupation. The Syonan Times, 25 February 1942, p. 3.

A newspaper notice listing the prices of basic food items at the start of the Japanese Occupation. The Syonan Times, 25 February 1942, p. 3.Black market trading was dangerous territory. If a nasty or desperate neighbour reported unusually lavish food consumption or the sudden availability of scarce medicine, the household could expect a visit from the dreaded Kempeitai, who paid for such inside information with cash or food. Because of the surreptitious nature of the black market, it provided numerous jobs for “runners”, or people who made a commission whether in kind or cash by connecting buyer with seller. Tan Cheng Hwee described it thus:

“If you have something [of value], you ask one after another whether you require this thing or not. And probably that chap will say ‘Okay, I’ll try and sell for you’. Then it goes like this, from one person knowing until, in the end, 20 people know about it. Then the sale will go through… anything from measuring tape… to gold.”14

Chu Shuen Choo, another war survivor, recalled that things like food or medicines bought from the black market had to be hidden carefully, “otherwise you will be queried ‘where did you get this?’ and then you will get into trouble”.15

Growing Your Own Food

In order to develop self-sufficiency, the Japanese administration held exhibitions that taught people how to cultivate their own food. Seeds for crops were sold cheaply or given away. Radio Syonan broadcasted talks about food cultivation, and detailed instructions were published in the daily newspaper, The Syonan Shimbun.

School fields were turned into vegetable plots and schoolchildren had to spend part of the time tending their vegetable plots. Any piece of land that could be easily used to cultivate food crops was made over. The best known of these conversions was the Padang fronting the Municipal Building,16 which was turned into a tapioca field. Other common crops were sweet potatoes, various types of beans, kangkong (water convolvulus), bayam (spinach), mustard greens, and gourds such as bitter gourd and bottle gourd. All fruits, even tropical varieties such as rambutans, durians and mangosteens, were considered a luxury as fruit trees took time to mature and when they produced fruit, it was only seasonally.

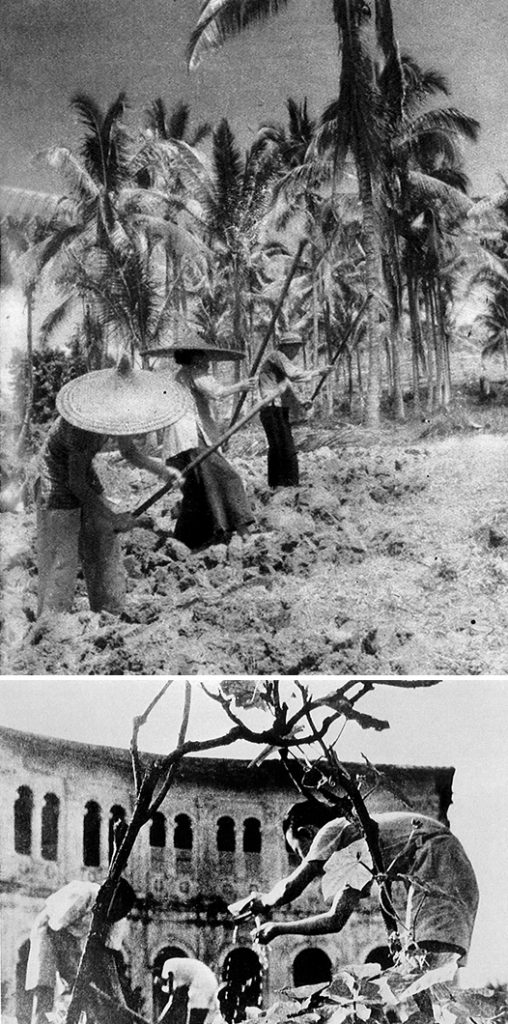

(Top) People were encouraged to grow vegetables, sweet potatoes and tapioca during the Japanese Occupation. Image reproduced from Lee, G.B. (2005). The Syonan Years: Singapore Under Japanese Rule 1942–1945 (p. 165). Singapore: National Archives of Singapore and Epigram. (Call no.: RSING q940.53957 LEE-[WAR]).

(Top) People were encouraged to grow vegetables, sweet potatoes and tapioca during the Japanese Occupation. Image reproduced from Lee, G.B. (2005). The Syonan Years: Singapore Under Japanese Rule 1942–1945 (p. 165). Singapore: National Archives of Singapore and Epigram. (Call no.: RSING q940.53957 LEE-[WAR]).(Bottom) The ground in front of St Joseph’s Institution on Bras Basah Road was turned into a vegetable garden as was every spare bit of land in Singapore including the Padang. Image reproduced from Lee, G.B. (2005). The Syonan Years: Singapore Under Japanese Rule 1942–1945 (p. 163). Singapore: National Archives of Singapore and Epigram. (Call no.: RSING q940.53957 LEE-[WAR]).

There were several issues with developing food sufficiency in Singapore. Few people knew much about farming or keeping livestock and, to make matters worse, the island’s soil for the most part was not rich in nutrients. As chemical fertilisers were not available, some resorted to enriching the land with human faeces and urine, but this practice ran the risk of contamination and the spread of intestinal parasites such as tapeworms and food-borne diseases.

Keeping livestock posed its own share of challenges as there was no access to animal feed. Food scraps were scarce too as practically nothing was thrown away and people usually cleaned off their plates when they sat down to a meal.

Necessity being the mother of invention, some were quite creative in addressing these issues. In an oral history interview, Lee Tian Soo, then a student living in Chinatown, recalled:

“I kept 20 to 30 fowls. We used to buy small chickens and then we looked after them… We had to look for something to feed the chickens. So we used to go down the drains with a candle to look for cockroaches. We would put them in a bottle and the next morning, we fed them to the chickens. Those chickens grew very fast.”17

Whatever that could not be eaten or was unpalatable was chopped up and fed to livestock along with duckweed to add bulk. Another survivor, Tan Sock Kern, nurtured a couple of goats that were given by an Indian friend into a small flock. Goats, she found, were easy to keep as they ate grass and, better yet, produced milk.18 Stray cats and dogs sometimes disappeared from the streets and into cooking pots. Kwang Poh, who sold cats and dogs for food, even did the slaughtering when asked to do so.19

The military began a campaign to return people from Malaya who were not originally from Syonan to their hometowns up north. They were soon joined by residents from Singapore who, out of their volition, also travelled north to stay with relatives in Malaya where there was easier access to homegrown rice and food. To reduce the pressure on food supplies, the Syonan administration began resettling people outside Syonan in remote makeshift villages where they were encouraged to grow their own food.

There was at least one small settlement for Indians on Batam. The Eurasian and Chinese Catholic settlement was located in Bahau, in Negeri Sembilan. The largest and most successful was the Chinese settlement in Endau, Johor. Bahau was an unmitigated disaster. The land there was hilly and the soil poor with no ready access to water. Malaria was particularly rampant and killed off the very old and the very young. Apart from malaria, the settlers knew little about crop cultivation. Weakened by disease and malnutrition, farming became too difficult. Bahau saw some 3,000 settlers – men, women and children – moving from Singapore in search of a better life. By the time the Occupation ended, between 300 and 1,500 people had died in Bahau (the exact figures are unknown).

The first settlers to Bahau – mainly young, single men – had to clear the land, build a rudimentary road from the train station to the camp and set up basic infrastructure before the families started arriving (Japanese propaganda photo). Courtesy of Father René Nicolas.

The first settlers to Bahau – mainly young, single men – had to clear the land, build a rudimentary road from the train station to the camp and set up basic infrastructure before the families started arriving (Japanese propaganda photo). Courtesy of Father René Nicolas.In Endau, malaria was less of a problem and the community had leaders who had some knowledge of agriculture. Endau settler Chu Shuen Choo said in her oral history interview:

“We had fruits, we had vegetables. … We had fish from the stream, eggs… a few ducks which, when we felt like eating, we just cut them up and ate them. … We had pork… And I would buy gula melaka (palm sugar) because my children wanted to eat sweets. We had no money to buy sweets, so I would cut this gula melaka into small portions, put them in the bottle. So whenever they wanted anything to eat, my sister would say ‘There is your gula melaka. Go and take’.”20

At the end of the Occupation there were some Endau settlers who chose to remain there rather than return to Singapore. For the town dwellers, part of the attraction of Endau or Bahau had been the freedom from Kempeitai surveillance even though they knew they were opting for an uncertain life as “farmers”.

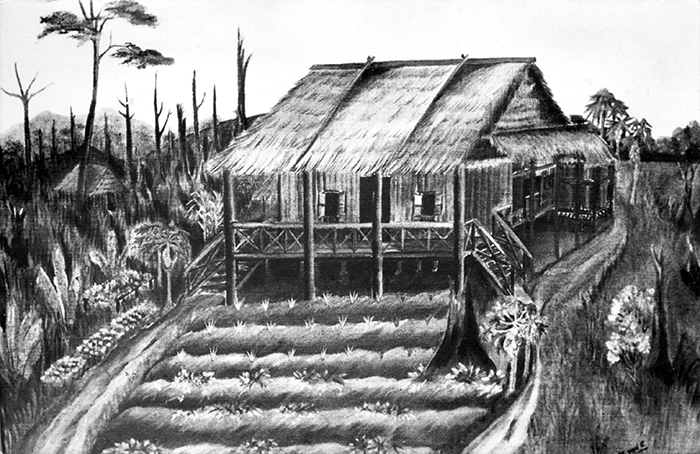

Painting of a hut belonging to Dr John Bertram van Cuylenburg and Mrs van Cuylenburg in the Bahau settlement. The painting was done by Mrs van Cuylenburg in 1945. In 1943, due to food shortages in Singapore, the Japanese administration launched resettlement schemes to relocate people to farming communities in Endau in Johor and Bahau in Negeri Sembilan. F.A.C. Oehlers Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Painting of a hut belonging to Dr John Bertram van Cuylenburg and Mrs van Cuylenburg in the Bahau settlement. The painting was done by Mrs van Cuylenburg in 1945. In 1943, due to food shortages in Singapore, the Japanese administration launched resettlement schemes to relocate people to farming communities in Endau in Johor and Bahau in Negeri Sembilan. F.A.C. Oehlers Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Wartime Victuals

With rice supplies drying up, tapioca, sweet potato and ragi (a type of millet) became the default staples in occupied Singapore. Tapioca and sweet potato were fairly easy to grow, especially tapioca, but it wasn’t pleasant to eat on its own. Tapioca that was made into noodles became rubbery when cooked. Bread was made with non-wheat flours, which yielded a tough loaf that sometimes had to be fried to make it remotely edible.

Chu Shuen Choo described ragi as “black stuff like sago. And we used to cook it like sago. Put scraped coconut on top of it and make it sweet, and eat it like a sort of cake to substitute rice. Otherwise we would be so hungry the whole day”.21 Cooking oil was scarce, so people had to make do with palm oil. Chu’s family would make their own coconut oil by boiling down coconut milk, and used their palm oil rations for lighting oil lamps instead.

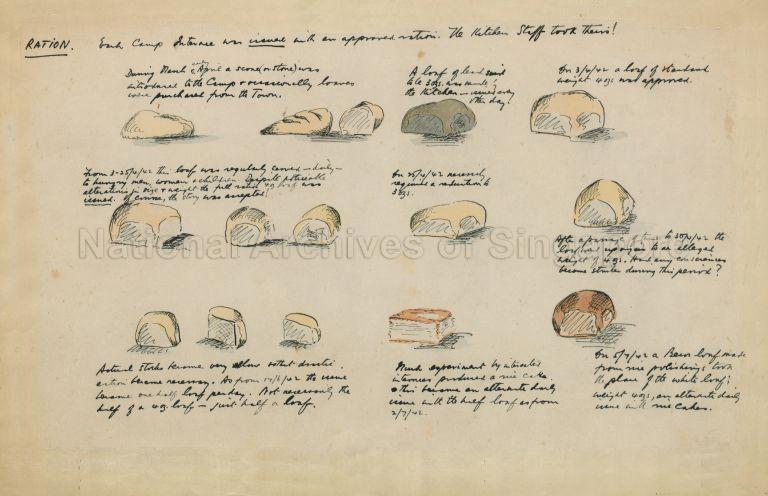

William R.M. Haxworth was the Chief Investigator at the War Risk Insurance Department in Singapore when he was interned during the Japanese Occupation, first at Changi Prison then at Sime Road Camp. During his internment, Haxworth produced more than 300 paintings and sketches depicting the terrible living conditions in the prisoner-of-war camps. This sketch titled “Bread Ration” takes a humorous look at the fluctuating portion sizes of prison rations as well as the internees’ attempts at baking, with their “scones” resembling “stones”. W.R.M. Haxworth Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

William R.M. Haxworth was the Chief Investigator at the War Risk Insurance Department in Singapore when he was interned during the Japanese Occupation, first at Changi Prison then at Sime Road Camp. During his internment, Haxworth produced more than 300 paintings and sketches depicting the terrible living conditions in the prisoner-of-war camps. This sketch titled “Bread Ration” takes a humorous look at the fluctuating portion sizes of prison rations as well as the internees’ attempts at baking, with their “scones” resembling “stones”. W.R.M. Haxworth Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.The phrase “a tasty wartime meal” sounds like an oxymoron, but a tasty dish simply requires aromatic ingredients. Although shallots, onions and garlic did not thrive in Singapore and had been imported before the war, there were other traditional aromatics that fared well here with minimal fertilising. Among these were ginger, serai (lemongrass), lengkuas (greater galangal or blue ginger), krachai (lesser galangal or finger root), limau perut (kaffir lime), limes, turmeric and chillies. Some even grew wild. Other typical Southeast Asian ingredients such as dried shrimps, ikan bilis (anchovies) and belacan (shrimp paste), were also fairly accessible as both were produced in Malayan coastal fishing villages.

Tan Cheng Hwee said: “I used to cook long beans with a bit of dried prawns and belacan. I brought it to work and throughout this time, I was eating this sort of food.”22 With just a combination of three basic ingredients – salt, belacan and chilli – one could prepare a reasonably tasty dish of, say, sweet potato leaves. Adding coconut milk made the dish even tastier. Coconuts were easily available as there were coconut trees everywhere even though coconuts were a controlled commodity. Coconut pulp could be finely ground and used to thicken gravy as well as add bulk and dietary fibre to a dish, while coconut water is tasty and rich in vitamin C.

Salt, an essential ingredient in food, was abundant, with Singapore surrounded by sea water. Palm sugar was used as a sweetener and, in lieu of soya sauce, there was fish sauce, also easily made by allowing small fish and salt to ferment in barrels placed in the sun. Coastal villages in Punggol, Pasir Ris and Pasir Panjang were inhabited by Malay fishermen who engaged in fishing. Because so much of the island was still rural, there was a small supply of chickens, ducks, eggs and pork as well as some market gardening produce.

The availability of such food was, of course, confined to those with the ability to pay for them. For most, the wartime diet was wholly inadequate. Many people, especially children, suffered from diseases caused by malnutrition, such as rickets, beriberi, pellagra, scurvy and anaemia. People fell ill easily because their immune systems were compromised. Malaria was rampant as were water-borne diseases like typhoid and dysentery. Water had to be boiled, requiring the use of fuel and matches that were difficult to come by.

The drugs necessary to treat various diseases were not available or hard to procure, and the food needed to keep people healthy or aid in the recovery of those who were ill were beyond the reach of the poor. All this had a profound impact on the survivors of the Japanese Occupation. Thereafter, their mantra would be “Do not waste food”, repeated frequently to a post-war generation of young people who would grow up in the midst of relative plenty.

Rationing remained in full force even after the British returned in 1945 and more stocks of food and other essentials began coming in. Image reproduced from Lee, G.B. (2005). The Syonan Years: Singapore Under Japanese Rule 1942–1945 (p. 159). Singapore: National Archives of Singapore and Epigram. (Call no.: RSING q940.53957 LEE-[WAR]).

Rationing remained in full force even after the British returned in 1945 and more stocks of food and other essentials began coming in. Image reproduced from Lee, G.B. (2005). The Syonan Years: Singapore Under Japanese Rule 1942–1945 (p. 159). Singapore: National Archives of Singapore and Epigram. (Call no.: RSING q940.53957 LEE-[WAR]).LEMAK SWEET POTATOES AND KANGKONG

This recipe, courtesy of the late Kathleen Woodford of the Eurasian Association, Singapore, is a typical wartime dish that made use of ingredients that were easily available during the lean years of the Japanese Occupation. Both recipe and photo are reproduced from Wartime Kitchen: Food and Eating in Singapore, 1942–1950 written by Wong Hong Suen and published in 2009 by Editions Didier Millet and the National Museum of Singapore (Call no.: RSING 641.30095957 WON).

Ingredients

500 g sweet potatoes, peeled and cut into pieces

500 g kangkong, cleaned and cut

2 cups coconut milk

Salt to taste

1 tablespoon oil

1 tablespoon dried shrimps

4 shallots

5 fresh chillies

Instructions

• Heat the oil in a saucepan before frying the pounded ingredients for a few minutes.

• Add the coconut milk and sweet potatoes and simmer till the latter are soft.

• Add the kangkong and boil.

• Adjust the seasoning to taste.

Lee Geok Boi is the author of several books on the Japanese Occupation of Singapore and a prolific writer of cookbooks on Asian cuisines, particularly Southeast Asian recipes and culinary traditions.

Lee Geok Boi is the author of several books on the Japanese Occupation of Singapore and a prolific writer of cookbooks on Asian cuisines, particularly Southeast Asian recipes and culinary traditions.

NOTES

-

Kwa, C.G., Heng, D., & Tan, T.Y. (2009). Singapore: A 700-year history: From early emporium to world city. Singapore: National Archives of Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 959.5703 KWA-[HIS]) ↩

-

Koh, T., et al. (Eds.). (2006). Singapore: The encyclopaedia (p. 24). Singapore: Editions Didier Millet in association with National Heritage Board. (Call no.: RSING 959.57003 SIN-[HIS]) ↩

-

Singapore. Department of Statistics. (1983). Economic & social statistics Singapore 1960–1982 (p. 4). Singapore: Dept. of Statistics. (Call no.: RSING q315.957 ECO). The land use figure was taken from 1950. Pre-war figures would have been similar or even less. ↩

-

Singapore. Department of Statistics, 1983, p. 7. ↩

-

Huff, G., & Majima, S. (Trans. & Ed.). (2018). World War II Singapore: The Chosabu reports on Syonan (p. 4). Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.5703 WOR-[HIS]) ↩

-

The Chosabu was set up in Syonan by a team of Japanese academics and civil servants to collect statistics aimed getting a better understanding of Singapore, a key port city in the region. Such an understanding was critical to Japan’s plans for the realisation of its Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, a rationalisation for its military expansionism. ↩

-

Huff & Majima, 2018, p. 4. ↩

-

Lee, G.B. (2005). The Syonan years: Singapore under Japanese rule 1942–1945 (p. 55). Singapore: National Archives of Singapore and Epigram. (Call no.: RSING q940.53957 LEE-[WAR]). The figure for British troops taken captive varies from about 100,000 to 130,000. ↩

-

Kratoska, P.H. (2018). The Japanese occupation of Malaya and Singapore, 1941–1945: A social and economic history (p. 14). Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.5103 KRA) ↩

-

Singapore. Department of Statistics, 1983, p. 10. ↩

-

Low, L.L. (Interviewer). (1984, April 12). Oral history with Tan Cheng Hwee [Transcript of recording no. 000416/14/9, p. 112–113]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

The term “banana money” derived its name from the motif of the banana plant stamped on the $10 note. The initial issue of “banana money” had serial numbers and contained safety features such as a watermark and a security thread. Over time, these features were dropped as the Japanese military issued more notes and in larger denominations whenever it ran out of money. This led to hyperinflation and a sharp fall in the value of the currency. ↩

-

Tan, B.L. (Interviewer). (1986, December 14). Oral history interview with Chua Eng Cheow [Transcript of recording no. 000722/16/10, p. 133]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Low, L.L. (Interviewer). (1984, April 2). Oral history interview with Tan Cheng Hwee [Transcript of recording no. 000416/14/6, pp. 72–73]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Low, L.L., & Tan, B.L. (Interviewers). (1984, August 22). Oral history interview with Chu Shuen Choo @ Mrs Gay Wan Guay [Transcript of recording no. 000462/12/5, p. 69]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

During the Japanese Occupation, the Municipal Building was made the municipal headquarters of the Japanese forces. When Singapore was granted city status on 22 September 1951, the building was renamed City Hall. Today, the former City Hall and the former Supreme Court adjoining it have been converted into the National Gallery Singapore. ↩

-

Low, L.L. (Interviewer). (1983, May 14). Oral history interview with Lee Tian Soo [Transcript of recording no. 000265/7/3, p. 31]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Yeo, G.L. (Interviewer). (1993, October 20). Oral history interview with Tan Sock Kern [Transcript of recording no. 001427/20/15, p. 225]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Ng, S.Y. (Interviewer). (1983, March 10). Oral history interview with Kwang Poh [Transcript of recording no. 000256/14/9, p. 110]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Low, L.L., & Tan, B.L. (Interviewers). (1985, March 25). Oral history interview with Chu Shuen Choo @ Mrs Gay Wan Guay [Transcript of recording no. 000462/12/9, p. 120–121]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Low, L.L., & Tan, B.L. (Interviewers). (1984, August 22). Oral history interview with Chu Shuen Choo @ Mrs Gay Wan Guay [Transcript of recording no. 000462/12/6, p. 79]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Low, L.L. (Interviewer). (1984, March 3). Oral history interview with Tan Cheng Hwee [Transcript of recording no. 000416/14/5, p. 63]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩