Give Me Shelter: The Five-footway Story

The five-footway – the equivalent to the modern-day pavement or sidewalk – was a hotly contested space in colonial Singapore. Fiona Lim relives its colourful history.

“Crowded, bustling, layered, constantly shifting, and seemingly messy, these sites and activities possess an order and hierarchy often visible and comprehensible only to their participants, thereby escaping common understanding and appreciation”.1

It may seem surprising in today’s context but the concept of a “messy urbanism” as defined by academics Jeffrey Hou and Manish Chalana is an apt description of Singapore in the 19th and mid-20th centuries. Such a phenomenon was played out in the five-footways of the town’s dense Asian quarters, including Chinatown, Little India and Kampong Glam.

Before Singapore’s skyline was dominated by soaring skyscrapers and high-rise flats, the most common architectural type was the shophouse. A typical shophouse unit comprises a ground-floor shop and a residential area above that extends outwards, thus increasing the living space above and creating a sheltered walkway below called the “five-footway”, between the street and entrance to the shophouse. Today, depending on the area, shophouses are highly sought after as commercial spaces or as private residences; they rarely function as both shop and house.

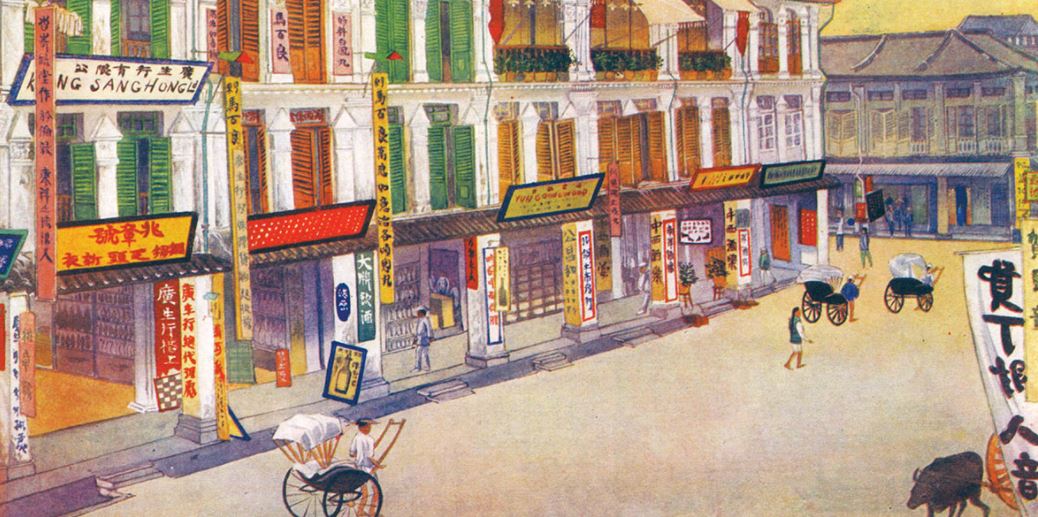

Early paintings of Singapore by Government Surveyor of the Straits Settlements John Turnbull Thomson – such as “Singapore Town from the Government Hill Looking Southeast” (1846) and “View of Chinatown from Pearl’s Hill” (1847) – feature contiguous rows of shophouses in the town centre. But what was not depicted in these early paintings, often framed from a considerable distance, was the bustling local life unfolding within the five-footways.

The Mandatory Five-footway

The five-footway (historically, often used interchangeably with the term “verandah”) was originally mandated by Stamford Raffles as part of his 1822 Town Plan of Singapore – also known as the Jackson Plan. Article 18 of the plan states: “Description of houses to be constructed, each house to have a verandah open at all times as a continued and covered passage on each side of the street.” This was to be carried out “for the sake of uniformity” in the townscape.2 Raffles’ intention to have the verandah “open at all times” would be frequently invoked in future contentions about the use of this space.

Scholars suggest that Raffles became acquainted with this architectural feature during his time as Lieutenant-General of Java. The Dutch colonisers had earlier introduced covered walkways and implemented a regular street alignment in Batavia (present-day Jakarta), capital of the Dutch East Indies.3

In the late 19th and right up to the mid-20th century, an assortment of traders, from tinsmiths, barbers and cobblers to letter writers and parrot astrologers, conducted their businesses along the five-footways, while hawkers peddled food, drinks and even household sundries.

Operating in the five-footway required minimal capital, and thus it was the most viable option for those with little means. In turn, vendors could provide essential goods and services to consumers cheaply. The five-footway came to sustain the economic and social life of a working class of mainly immigrants who had come to Singapore to find work, hoping to give their families back home a better life.

Although the lives of Asian migrants in Singapore were steeped in this ecosystem, many Europeans found this vernacular environment appalling. Those who considered this social space as a novelty tended to view it as “exotic”, as John Cameron, former editor of The Straits Times, did when he wrote: “[I]n a quiet observant walk through [the five-footways] a very great deal may be learned concerning the peculiar manners and customs of the trading inhabitants.”4

British traveller and naturalist Isabella Bird was similarly taken by the liveliness of the five-footways when she visited Singapore in 1879:

“… more interesting still are the bazaars or continuous rows of open shops which create for themselves a perpetual twilight by hanging tatties or other screens outside the sidewalks, forming long shady alleys, in which crowds of buyers and sellers chaffer over their goods.”5

The “Five-footway” Misnomer

The five-footway was historically known as the verandah, kaki lima, ghokhaki or wujiaoji (五脚基) – the latter three meaning “five feet” in Malay, Hokkien and Mandarin, respectively. However, these vernacular names and the commonly used “five-footway” are in fact misnomers: few of these walkways are actually 5 feet (1.5 m) wide as the regulation for the width of the path changed over time.

While the earliest verandahs spanned 5 or 6 feet (1.5 or 1.8 m), from the 1840s onwards, the law decreed that the path should be at least 6 feet wide. In 1887, the stipulated width extended to 7 feet (2.1 m), and subsequent legislations decreed a minimum of 7 feet. A 1929 by-law declared that footways in the busy thoroughfares of Chulia Street, Raffles Place and High Street should be at least 8 feet (2.4 m) wide, with no more than two feet of space occupied.6

Life in the Five-footway

Depending on which part of town a traveller was exploring, he or she might be in for a rude shock if they believe the following description of the five-footway (c. 1840) by Major James Low, a long-time employee of the Straits Civil Service:

“A stranger may well amuse himself for a couple of hours in threading the piazas [sic] in front of the shops, which he can do unmolested by sun, at any hour of the day.”7

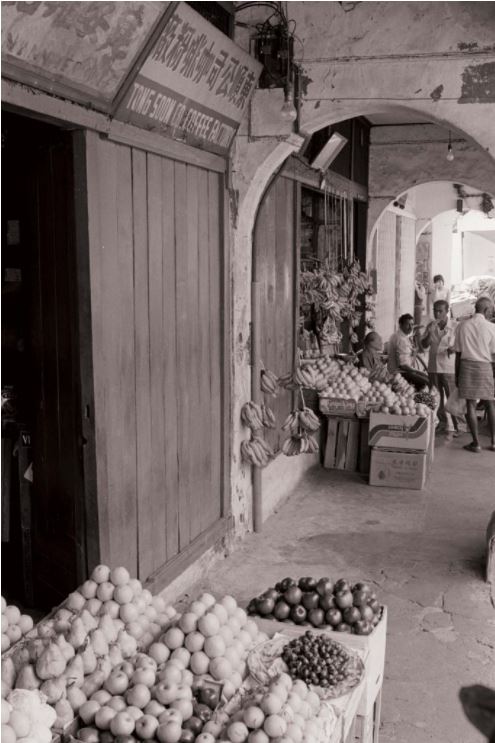

In reality, the five-footways in the town’s Asian quarters teemed with so much obstruction and activity that pedestrians were all too often forced onto the road.

Low’s view was not a popular one. In 1843, a disgruntled individual offered a sharply contradictory experience in a letter to The Singapore Free Press, arguing for the public right of way:

“[The verandah] is or was intended to provide for the accommodation of the public by furnishing them with a walk where they might be in some degree free from the sun and dust, and be in no danger of sudden death from numerous Palankeens that are always careering along the middle of the way. But this seems to have been forgotten, and the natives have very coolly appropriated the verandahs to their own special use by erecting their stalls in it and making it a place for stowing their goods.”8

The five-footway was originally intended for the use of pedestrians. Not only would the sheltered path provide respite from the tropical heat or a sudden downpour, it also served as a safe path away from road traffic. However, over time, the Asian communities began to use the five-footway for their own purposes, according to their needs and the realities of the day.

Pragmatic shop owners often used the five-footway outside their shop to store or display goods. The more enterprising ones rented out parcels of space to other small vendors – an attractive deal considering the good flow of human traffic and low overheads. Soon, all sorts of trades and activities began occupying the five-footways.9

In the Kampong Glam district, designated as the Arab quarters in Raffles’ 1822 Town Plan, the five-footways became thriving sites for Bugis, Arab and Javanese businesses and all manner of Islamic trade. On Arab Street, historically referred to as Kampong Java, Javanese women sold flowers along the shophouse verandahs. So famous was this street for its flower trade that it was known as Pookadei Sadakku (Flower Street) in Tamil.

Meanwhile, lined up along the five-footways of nearby Bussorah Street were ambin, or platforms, on which people could rest or have a shuteye. Rosli bin Ridzwan, who grew up on Bussorah Street, recalled that whenever an elderly person was seated on the ambin, younger ones would greet him or her and promptly walk on the road alongside as a show of deference.10

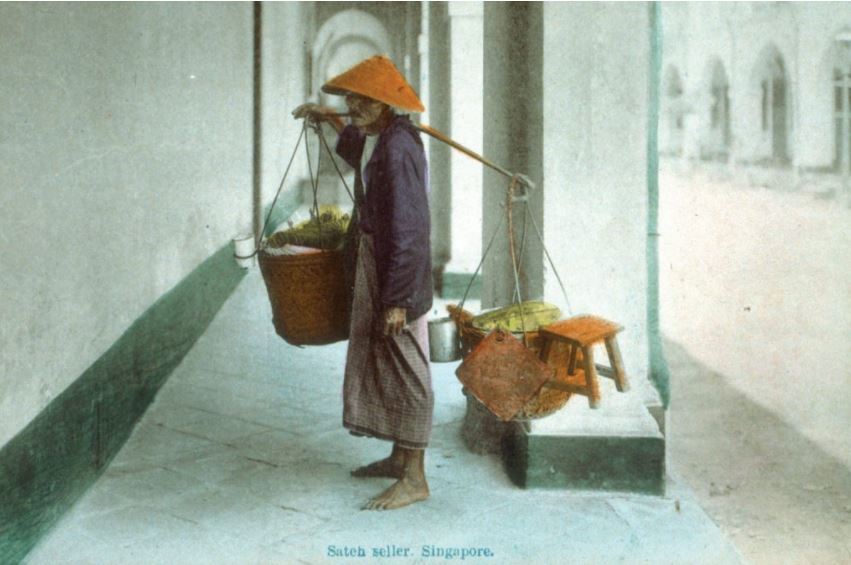

The most common occupant of the five-footway was probably the food vendor. Hawkers were either itinerant, meaning they would move around looking for customers, or they might occupy a fixed spot on the five-footway or on the kerbside, sometimes even extending their makeshift stalls onto the road with tables and chairs. All manner of food was sold, including satay, laksa, “tok-tok” noodle, putu mayam and kacang puteh. During lull periods, some hawkers laid down their wares and took a nap in the five-footways.

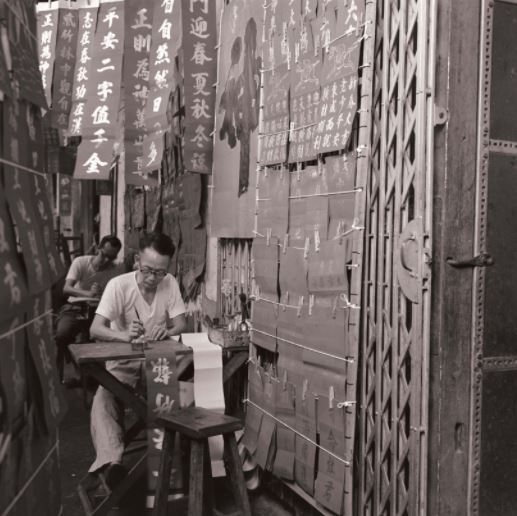

Besides food, one could find tradesmen and women engaging in various occupations that supported the inhabitants of the densely populated Chinatown. Letter-writers armed with ink and brush penned letters for illiterate customers or wrote festive couplets for Chinese celebrations.11 Barbers simply pulled out a chair and hung a mirror on the wall in front before providing haircuts and shaves for customers.12

Foong Lai Kum, a former resident of Chinatown, remembered a man known as jiandao lao (剪刀佬; colloquially “Scissors Guy” in Mandarin) plying his trade on the five-footway of Sago Lane, sharpening the scissors used by young women working at rubber factories, or the knives used by hawkers or butchers.[^13] And, thanks to the itinerant pot mender, one never had to shell out money for a new pot.13

Five-footway traders were also found in the Serangoon Road area, today’s Little India. The lady selling thairu (curd) would be perched on a step, with packets of the Indian staple displayed on a wooden crate. On another five-footway nearby was the paanwalla, who prepared the betel-leaf-wrapped snack known as paan. Indian parrot astrologers were also a common sight: based on the customer’s name and date of birth, these fortune tellers used green parakeets to pick a numbered card inscribed with the customer’s fortune from a stack.14

During festive occasions like Hari Raya, Deepavali and Chinese New Year, shop owners and vendors packed the five-footways, with their goods often spilling onto the streets. And whenever a wayang (Chinese opera) performance or other communal event was staged, the five-footway became part of the viewing arena.

At dusk, as traders wound up for the day, residents gathered at the five-footway for a conversation, to smoke opium or just enjoy the fresh air. Many shophouse residences were occupied by coolies and samsui women, who each rented a tiny cubicle out of the many that had been carved up for subletting in a single unit. This resulted in cramped living quarters with poor ventilation. Unsurprisingly, residents preferred to relax outdoors after a hard day’s work, and often the only available space was the five-footway below. Some even opted to sleep there at night as it was airier than their dank and overcrowded cubicles.15

The five-footway did not merely serve economic needs – it was also a space for social interaction. Rather than being just a “conduit for human traffic” as it had originally been intended, academic Brenda S.A. Yeoh suggests that Asians perceived the five-footway in a “more ambivalent light”, such that the space was “sufficiently elastic to allow the co-existence of definitions”.16 It was precisely this flexibility of use that created the colourful multiplicity of local life found in the five-footways.

A Public Health Threat

While mundane daily life unfolded in the five-footways, the authorities were dogged by sanitary issues such as clogged drains and sometimes even abandoned corpses. A strongly worded letter published in The Straits Times in 1892 by the municipal health officer accused “vagrant stallholders” of dumping refuse and bodily excretions into drains, causing an “abominable stench”.17

An exasperated member of the public echoed this sentiment in 1925, calling the obstruction by hawkers a “grave menace not only to the safety but also to the cleanliness and order of the town”.18 The congestion of the five-footways prevented the municipality from carrying out sanitation works, such as the maintenance of drains. Over the years, the campaign to remove five-footway obstruction was often couched in the interests of public health and hygiene.

Adding to the public health threat was the issue of visual disorder, which was also anathema to the government. An article published in 1879 in the Straits Times Overland Journal bemoaned the state of chaos along the five-footways:

“It is not too much to say that there is no well-regulated city in this world in which such a state of affairs as can be daily seen, in say China Street, would be permitted.”19

Some Europeans also floated orientalist – and ultimately racist – conceptions of Asians in Singapore.

An 1898 article in The Singapore Free Press charged that the practice of obstructing a public walkway was “essentially Eastern” and attributed this to the Asians’ supposed lack of civility, “as the large majority of those… have been born and brought up in places where our more civilised views do not prevail… it is the more difficult for the authorities to secure obedience to their wishes”.20

Whose Right of Way?

As the public and private spheres met in the liminal space of the five-footway, conflict over the right of use became inevitable. Almost from the very start, the verandah had been a thorny issue for the municipal authorities. Members of the public – mainly Europeans – expressed their frustration at having to jostle for space with vendors and their wares, along with shops whose goods occupied the entire walkway and the odd coolie having a siesta. Complaints revolved around the “risk of sunstroke or being run over” as pedestrians had to walk along the side of the road.21 Meanwhile, the municipality faced great difficulty in regulating the verandah for pedestrian use.

Conflict over the use of the footways persisted for over a century, with the “Verandah Question” becoming a hotly debated topic in many municipal meetings. In 1863, it seemed that the municipal commissioners and frustrated pedestrians had won the battle when the court ruled that all verandahs were to be “completely cleared and made available for passenger traffic”.22

However, as few people actually adhered to the regulation, the encumbrance of the five-footways continued, much to the chagrin of law enforcers. Finally, in July 1887, legislation was passed granting municipal officers the power to forcefully clear the five-footways and streets of any obstructions. The perceived incursion into the space used by the Asian communities resulted in a three-day strike and riot in February 1888 (see textbox below).

Nonetheless, the five-footway trade and the various obstructions continued unabated – as did complaints by the Europeans – with the Asians fighting back against any threat to their livelihoods and way of life. At the end of the 19th century, the municipal authorities decided that it would be impossible to enforce a completely free passageway; instead, they sought a compromise such that vendors could carry on with their trades as long as they were itinerant and did not encroach on any particular area for prolonged periods.

By 1899, the five-footway problem was referred to as the “very old Verandah Question” in the press,23 with the situation devolving into a game of “whack-a-mole” as officials sought out “obstructionists” and meted out fines to offenders. On 26 September 1900 alone, 70 individuals were fined $5 each for obstructing the five-footway.24 However, as the sheltered walkway was a transient space that saw the movement of both humans and goods, the task of completely eradicating occupation of the five-footways proved rather onerous. A letter to The Straits Times in 1925 said as much:

“The most insidious and worst kind of obstruction is the temporary one. It consists generally of merchandise being either despatched from or received into a godown. In reality the obstruction is permanent, because as soon as one lot is removed another takes its place.”25

From 1907 onwards, night street food hawkers were subject to licensing by the authorities. After Singapore’s independence in 1965, food peddlers were moved into new standalone hawker centres. Nevertheless, the occasional itinerant food vendor could still be spotted along five-footways up until the 1980s. Over time, other five-footway traders also disappeared as the rules and their enforcement were tightened. Those with the means could relocate to a permanent location, while others simply gave up their trade for good.

Resurgence of an Old Problem

In 1998, the problem resurfaced when Emerald Hill in the Orchard Road district was redeveloped into a nightlife area. To promote vibrancy in Emerald Hill, the Urban Redevelopment Authority permitted the use of the five-footway for food-and-beverage businesses. However, this drew the ire of a long-time resident, who said she was deprived of “the seamless, sheltered stroll she used to enjoy”, denying her the “equal right to that public space as intended by the town planners of yore”.26

In 2015, the popular nightlife at Circular Road near Boat Quay came under threat when the Land Transport Authority became stricter with countering pavement obstruction. Officials spotted “goods, tables and other materials” that had been “untidily” laid out on the streets, five-footways and back lanes of shophouses. This led to pedestrians having to skirt these obstructions and walk along the side of roads, causing them “inconvenience and danger”27 – a refrain that harks back to as early as the 1840s.

But one thing has changed: the use of the five-footway for business is today framed in terms of culture and heritage as people feel that allowing a more flexible use of the five-footway would help preserve the “city’s character”.28

These days, albeit rarely, one may encounter a cobbler, florist or tailor on the five-footways of Little India, Chinatown or Kampong Glam, or shophouse businesses using the walkway space in front to display their goods.

Navigating Singapore’s five-footways today is still a more interesting way of experiencing the city compared to the modern air-conditioned shopping complex, where homogeneity and predictability reign.

On 21 February 1888, under orders from Municipal President T.I. Rowell, municipal inspectors began clearing away obstructions along five-footways in the Kampong Glam area. As the authorities moved towards North Bridge Road, many shopkeepers shuttered their shops in protest. Chinese secret societies also began fomenting unrest – they had a stake in the five-footway trade as they offered “protection” to vendors in their territories in return for a fee. Soon, tramcars entering the town centre became the target of people armed with stones, and had their windows smashed.

The violence escalated the following day. Secret society members hurled stones and bricks at people and vehicles in the vicinity of South Bridge Road, China Street, Canal Road, Boat Quay and North Bridge Road. Europeans who ventured into these areas were pelted with stones, with a number of them sustaining injuries. The town came to a standstill as no carriages or rickshaws dared to ply the area. The disruption continued into 23 February.

Following a deadly confrontation with the police, the riots were quelled and, on the third day, shops began reopening. In the following weeks, local newspapers became once again fixated with the “Verandah Question”. Eventually, the law was amended to relax the prohibition of five-footway obstruction – as long as the five-footway could accommodate people walking two abreast, the authorities took no action.

Fiona Lim is a freelance writer, editor and researcher who is interested in the complexities of a city and its people.

Fiona Lim is a freelance writer, editor and researcher who is interested in the complexities of a city and its people.

NOTES

-

Hou, J., & Chalana, M. (2016). Untangling the ‘messy’ Asian city (p. 3). In J. Hou & M. Chalana (Eds.), Messy urbanism: Understanding the “other” cities of Asia (pp. 1–21). Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. (Call no.: RSEA 307.76095 MES). ↩

-

Buckley, C.B. (1902). An anecdotal history of Singapore (Vol. 1, p. 84). Singapore: Fraser & Neave, Ltd. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

Lim, J.S.H. (1993). The ‘Shophouse Rafflesia’: An outline of its Malaysian pedigree and fits subsequent diffusion in Asia. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 66 (1) (264), 47–66, pp. 51–52. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Cameron, J. (1865). Our tropical possessions in Malayan India […] (p. 60). London: Smith, Elder and Co. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

Bird, I. ([1883]; 1967 reprint). The Golden Chersonese and the way thither (p. 150). Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.5 BIR). ↩

-

Yeoh, B.S.A. (2003). Contesting space in colonial Singapore: Power relations and the urban built environment (p. 272). Singapore: Singapore University Press. (Call no.: RSING 307.76095957 YEO). ↩

-

When local house rents were cheap. (1934, April 15). The Sunday Tribune, p. 19. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

[Untitled]. (1843, February 23). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

In the 1890s, the five-footway could be divided up into a maximum of four units and subleased, each paying a monthly rent of between $1 and $15. See Yeoh, 2003, p.247. ↩

-

National Heritage Board. (2012). Kampong Glam: A heritage trail (pp. 27, 35). Retrieved from National Heritage Board website. ↩

-

Yeo, L.F. (Interviewer). (2000, May 13). Oral history interview with Song Moh Ngai [Recording no. 002304/25/17]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Yeo, L.F. (Interviewer). (1999, October 6). Oral history interview with Sew Teng Kwok [Recording no. 002209/23/5]; Yeo, G.L. (Interviewer). Oral history interview with Kannusamy s/o Pakirisamy [Transcript of recording no. 000081/28/18, pp. 285–286]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website; Cameron, 1865, p. 66. ↩

-

Singapore. Archives & Oral History Department. (1985). Five-foot-way traders. Singapore: Archives & Oral History Department, p. 36. (Call no.: RDLKL 779.9658870095957 FIV). ↩

-

Siddique, S., & Shotam, N.P. (1982). Singapore’s Little India: Past, present, and future (pp. 101–104). Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. (Call no.: RSING 305.89141105957 SID). ↩

-

Oral history interview with Sew Teng Kwok, 6 Oct 1999. ↩

-

The municipal health officer on the verandah question. (1892, April 30). The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Street obstruction. (1925, July 11). The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

[Untitled]. (1879, May 7). Straits Times Overland Journal, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Street obstruction. (1898, July 7). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (Weekly), p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

On the verandah. (1898, February 26). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

News of the week. (1863, May 16). The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The verandahs again (July 6th). (1899, July 13). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (Weekly), p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

[Untitled]. (1900, September 26). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 11 Jul 1925, p. 10. ↩

-

Tan, S.S. (1998, April 10). Eat, drink on 5-foot ways. The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Yeo, S.J. (2015, July 5). Goodbye to al fresco dining? The Straits Times, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Hartung, R. (2015, July 31). Preserve the city’s character on the footways. Today, p. 22. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩