Head Count: The History of Census-taking in Singapore

The very first census here was conducted in 1824. Ang Seow Leng reveals how doing a headcount has evolved over the last 200 years.

Singapore’s population has grown steadily over the decades to reach a total population of 5.7 million as at June 2019.1

Population censuses provide vital surveys of individuals in order to understand the basic demographic composition and trends of a society. They are also useful for developing evidence-based policies in strategic planning and decision-making. In the case of Singapore, figures on population distribution by areas, for instance, are studied to plan the requirements for schools, markets, hospitals and other public amenities.

The Handbook on the Management of Population and Housing Censuses, published by the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs in 2016, defines a population census as “the total process of planning, collecting, compiling, evaluating, disseminating and analysing demographic, economic and social data at the smallest geographical level pertaining, at a specific time, to all persons in a country or in a well-delimited part of a country”.2

While huge amounts of resources are required to conduct a massive census exercise, the methods used in collecting data are equally important as these affect the quality and accuracy of the final results.

Censuses are conducted on either a de facto or de jure basis. The de facto population “consists of all persons who are physically present in the country or area at the reference date, whether or not they are usual residents”, while the de jure population is defined as “all usual residents, whether or not they are present at the time of the enumeration”.3

Patterns of global migration and settlements shape the demographic, social and economic histories of a country. For instance, Adam McKeown’s research showed that major long-distance migration flows in the years between 1846 and 1940 from India and southern China, and to a much lesser extent from Africa, Europe, North Eastern Asia and Middle East to Southeast Asia, the Indian Ocean Rim and the South Pacific, numbered around 48 to 52 million.4 These migration patterns make for interesting analyses and studies.

Early Censuses in Singapore

According to then Acting Colonial Secretary of the Straits Settlements Hayes Marriott, when Stamford Raffles arrived in Singapore in 1819, the estimated population size was around 150, including 30 Chinese and the Malays who had accompanied Temenggung Abdul Rahman when he settled in Singapore in 1811.5 The number of inhabitants soon grew exponentially. Raffles, writing to Henry Petty-Fitzmaurice, the 3rd Marquess of Lansdowne, on 15 April 1820 claimed:

“When I hoisted the British flag the population scarcely amounted to 200 souls, in three months the number was not less than 3,000 and it now exceeds 10,000 principally Chinese…”.6

Although primary records of the early censuses of Singapore are no longer available, they can be found in secondary sources such as newspapers and books. According to Charles Burton Buckley, one of Singapore’s earliest newspaper columnists, Singapore’s first census took place in January 1824. It recorded a population of 10,683, comprising 74 Europeans, 16 Armenians, 15 Arabs, 4,580 Malays, 3,317 Chinese, 756 Indians, and 1,925 Bugis, and others.7

Marriott reported that censuses were taken almost every year, from 1825 to 1860,8 but noted that the figures for these earlier censuses were unreliable. He pointed out that, in 1833, the census was carried out by two constables who were deployed to the settlement and had to attend to their primary duties on top of census-taking.9 Thomas John Newbold, a lieutenant with the Madras Light Infantry who moved to Melaka in 1832,10 also recorded the censuses of Singapore from 1824 to 1836, noting that a census was not taken in 1835. He did not list any figures for 1831.11

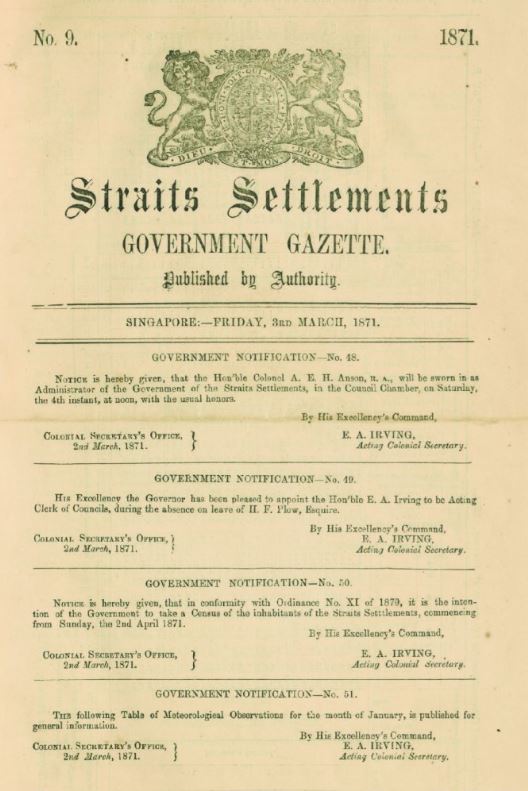

It was only on 2 April 1871 that the first systematic census of Singapore as part of the Straits Settlements was conducted.12 The Census Bill had been passed in October 1870 to collect more reliable data, conferred power on the Governor and Executive Council to formulate rules for taking the census and to impose punishments on those who refuse to cooperate.13 This bill was introduced at a time when the practice of taking a census once every 10 years was adopted throughout the British Empire. In 1871, the Singapore census took place around the same time that Great Britain and Ireland conducted theirs.14

The 1871 landmark census was different from the 1860 census, which Governor Harry Ord had dismissed. He wrote that “no great reliance can be placed upon the returns of the population stated to have been taken in that year [1860], so that for any purposes of comparison now, they are of little or no value”.15 The 1871 census, on the other hand, had trained enumerators to handle the census. The categories of data collected were also expanded from sex and race to include information on age, occupation, town-country divisions and the type of dwellings. The total population of Singapore at the time was 97,111.16

Successive censuses were carried out once every 10 years until 1931. It was observed during the 1931 census that all the non-Malay immigrants in Malaya were mainly sojourners who arrived here to seek a fortune without any intention of residing here permanently, and that the increase in the formation of a settled population of non-Malay origin had been very slow.17 The first pan-Malayan census began in 1921.18 Although preparations for the 1941 census had been underway, the onset of World War II derailed plans.

The Japanese Occupation Years

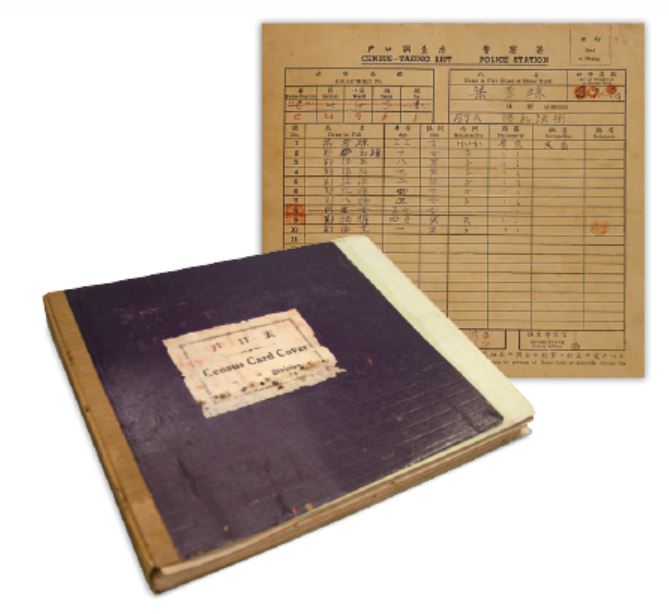

After Singapore fell to the Japanese in February 1942, the island became known as Syonan-to. During the Japanese Occupation (1942–45), the Chosabu (Department of Research) recruited Japanese academics and civil servants, and sent them to Southeast Asia to research Southeast Asian economies and societies for Japan’s administrators.19 One of the reports produced by the Chosabu in Singapore was “Population by Occupation in Syonan Municipality” in December 1943.

The Chosabu noted that the last population census had taken place in Singapore in 1931, and that the police stations on the island had conducted a census survey in April 1943. The same report recorded the approximate population as being around 855,679. This figure was derived from the category that recorded occupations in the April 1943 census survey. The information was used to “identify the circumstances among the population in regard to rationing and other matters”.20

The Chinese viewed the information-gathering with suspicion as they had suffered greatly during Operation Sook Ching from February to March 1942 when Chinese males between the ages of 18 and 50 were summoned to report at mass screening centres; anyone who was suspected of being anti-Japanese was executed. Hence, the report also noted that “for nationality, most Chinese responded with their home region but a few identified themselves only as Chinese. There was no consistency. The same is true of occupation”.21

Post-war Censuses

The first post-war census was conducted in 1947, after a lapse of 16 years. M.V. Del Tufo, Superintendent of the Census, wrote in the Foreword of the Report on the 1947 Census of Population that the Japanese Occupation had resulted in loss or destruction of records, and the lack of manpower and frequent strikes added to the challenges of carrying out the census.

To quell fear and distrust among people after the war, the British authorities explained that the “census had nothing to do with income tax or rice cards, nor would it be used as a check on individuals”.22 They also assured the people that “all the information with regard to individuals [would be] treated as confidential, and may not be used for any purpose other than preparing tables of statistics about the community as a whole”.23 At the time, there were thousands of squatters, mostly Chinese, who were living on lands that did not belong to them and they feared eviction if discovered during the census taking.24

Compared with the labour-intensive manual method of processing earlier censuses, the 1947 census used a mechanical method of punched cards to speed up the tabulation of the results. Deputy Superintendents of Census were appointed in the states of the Federation of Malaya, except in Perak where the Census Headquarters undertook the Deputy’s functions, and in Singapore. The Singapore census also included the populations residing in offshore islands such as Pulau Ubin, Pulau Tekong Besar and St John’s Island as well as those on Christmas Island and Cocos (Keeling) Islands. (The Cocos Islands and Christmas Island were transferred to Australia in 1955 and 1958 respectively.25)

The next census was conducted on 17 June 1957, with the Singapore Department of Statistics handling the census for the first time. It also marked the first time that the census was conducted only for Singapore.26

Post-independence Population Censuses

Singapore gained independence in 1965 and the first post-independence population census was conducted in 1970, 13 years after the 1957 census. This was based on recommendation by the United Nations (UN) that each country undertakes a population census during the year ending in “0” or as near to those years as possible. The UN held the view that “the census data of any country are of greater value nationally, regionally and internationally if they can be compared with the results of other countries which were taken at approximately the same time”.27 Subsequent censuses in Singapore saw a constant improvement in the coverage of data, fieldwork, method in collecting data and an increasing reliance on technology.

The 1970 census adopted the de facto concept and counted all persons present in Singapore at the time of the census enumeration. Then Minister for Finance Goh Keng Swee was the Chairman of the Census Planning Committee. The Superintendent of this census was P. Arunmainathan, and he was supported by 3,000 field workers comprising mainly teachers and students. The census involved the use of computer-generated data as well as a wider coverage of the types of data collected and the use of sampling population. A two-volume report was published in 1973.28

The census in 1980 saw new data collected, for instance, income from work, address of work place or school, and usual mode of transport to work and school. Then Minister for Trade and Industry Goh Chok Tong was the Chairman of the Census Planning Committee, while the Superintendent of Census was Khoo Chian Kim. About 2,600 people were employed for this exercise.29 Between 1981 and 1986, nine statistical releases and five census monographs on demographic trends, trends in language, literacy and education, labour force, household and housing, as well as geographic analysis, were published.

The Census (Amendment) Bill that was passed on 28 March 1990 allowed for the exchange of information between government bodies in order to facilitate data gathering during population census exercises, and thus avoid duplication of efforts. To preserve confidentiality and prevent the misuse of information, only the Superintendent of Census is able to obtain and share information.30

Then Minister for Trade and Industry Mah Bow Tan chaired the 1990 Census Planning Committee, with Lau Kak En as Superintendent. With the support of more than 2,000 people employed to conduct the census exercise during the peak period, it was the first time when details of Singaporeans and permanent residents abroad were included. This was also the first time a country used a census form that had been pre-printed with relevant particulars from various government databases.31 Six statistical releases and six census monographs were published between 1991 and 1996, covering almost the same topics as the 1980 census.

Singapore became one of the first countries in the world to submit census returns through the internet for the 2000 population census. In this census, Singapore adopted a register-based approach to census-taking for the first time, in which basic data from existing government databases were utilised, thus greatly reducing the need for data entry.32 With the adoption of a register-based census, the de jure concept based on a person’s usual place of residence was used instead.

In 1996, the Department of Statistics developed an integrated database system known as the Household Registration Database, which captured the basic count of individuals and the overall profile of the population, including information like age group, sex, ethnic group, citizenship and house-type.33 Only 20 percent of all households were surveyed in order to verify the accuracy of data.34 For these participating households, the census adopted a tri-modal data collection strategy that allowed residents to choose one out of three options to provide information: internet enumeration, computer-assisted telephone interview or the traditional face-to-face interview.35 This resulted in greater efficiency in data collecting and was less labour-intensive.

The Chairman for the Census 2000 Planning Committee was then Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of Trade and Industry Khaw Boon Wan, and the Superintendent was Leow Bee Geok. Five statistical releases and nine advance data releases were published between 2000 and 2001. These covered topics such as education, religion, literacy and language, economic characteristics, mode of transport, households and housing, household income growth and distribution, and marriage and fertility.

As the fifth census since independence, the exercise in 2010 also adopted a register-based approach in which the basic population count and characteristics were compiled from administrative sources. Hence, there was a reduction of field interviewers to only 140, with 20 field supervisors across 10 regional offices in the country. These interviewers also made use of mobile personal computers to carry out their enumeration on the go, thus removing the need for hardcopy survey forms. Another 400 daily-rated staff were recruited to support day-to-day operations. Ravi Menon, then Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of Trade and Industry, was the Chairman of the 2010 Census Planning Committee, with Chief Statistician Wong Wee Kim as Superintendent.36 In 2011, three statistical releases were releases were published on demographic characteristics, education, language and religion, households and housing, and geographic distribution and transport.

The Future of Census

Censuses allow a country to collect data on the demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of its population. Singapore has gone through 14 censuses since 1871, and each one has seen an increasing reliance on technology, especially in the recent censuses.

Emerging global trends have influenced the manner in which a census exercise is designed and undertaken, especially in developed countries. While the purpose of a census has evolved from its early days as a means for implementing taxation policies, and conscription into military service or forced labour, it has become a useful tool for social analysis and understanding as can be seen in the increasing number of census questions to gather more social statistics for successive censuses.37

Data collected during a census is crucial for any government for the purposes of long-term planning, decision-making and policy formulation. A thorough and detailed analysis of any census typically takes two years or more to complete, by which time the efficacy of the results might be called into question. One of the challenges in census-taking is the timely analysis of the findings so that these remain relevant and useful for the aforementioned purposes. Another challenge is the difficulty in capturing accurate demographic characteristics due to increasing migration and human mobility for work and study.

In a digital age where linked data and sophisticated data analysis tools are readily available, countries like Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Finland and Slovenia have moved away from traditional approaches in conducting a census. They now rely on centralised databases administered by the government such as tax records, electoral lists and school rolls, and also engage in periodic polling of a sample population size.38

Census data derived completely from administrative register-based sources do not require citizens to fill in census questionnaires. However, such a method is not without its drawbacks. The administrative sources may not be appropriate for census use as the information gathered is not meant for statistical purposes. Certain information may also not be available or complete in administrative databases.

It is common for countries, therefore, to adopt a combination of a register-based survey with enumeration or survey data, similar to what Singapore did in the 2000 and 2010 censuses; this will also be the case in the upcoming 2020 census.39 It will be interesting to see how Singapore’s future censuses keep up with evolving demographics and trends.

The author wishes to thank the Singapore Department of Statistics for reviewing the essay.

BITING DOGS, CAPSIZED BOATS AND STRIKING WORKERS: STORIES FROM THE 1947 CENSUS

By Jimmy Yap

In general, carrying out a census is no easy task. However, back when Singapore was not as urbanised as it is now, counting its inhabitants was particularly challenging. Newspaper accounts of how the 1947 census was conducted give a good sense of the issues faced by census takers (or enumerators as they are more properly known).

The 1947 census was an important one, being the first undertaken after the war. It was a massive exercise that included all towns, villages, people living in the jungles and on boats and houses built out at sea, and even passengers on trains.40

To incentivise enumerators, the Malayan Census Headquarters introduced a prize scheme under which $40,000 were given out in Singapore and the Malayan Union to the most efficient enumerators on the recommendation of the local headquarters.41

Besides using government department staff and teachers for census work, hundreds of schoolboys in Singapore were also recruited as enumerators and were each paid $40 for their efforts.42 About 80 scouts from the 10th Singapore Troop of St Andrew’s School also volunteered to assist in the taking of the census in the rural areas of Singapore.43

According to one news report, enumerators in the rural areas were frequently regarded with “extreme suspicion”:

“The country population, especially farmers are not always willing to open their doors. It takes a good five minutes to convince the occupants of some houses that census officers are not policemen, detectives or gangsters, but just people assigned by the Government to find out the number of people living in a house.

“This information must be obtained from the principal occupier of the house and if he does not happen to be in, as is often the case, the census officer has to make the long trek back at a time when his informant is likely to be home.”44

Another problem faced in the rural districts was that many houses were not marked on maps. “The census officer covers a district, then climbs up a hill for the house on top. When he reaches it and looks round the surrounding country he is almost always sure to spot a hut that he had overlooked because it was not marked. He is then obliged to go down again to fulfil his task.”45

In addition to swamps, rivers, jungles and suspicious tenants, the enumerators had to deal with dogs. The same news report said that “two of the men returned with dog bites while several others have been chased by dogs found in almost every house in the country”.46

Another challenge was to count those who lived off the main island of Singapore. In some cases, the government relied on the people who knew the area best – the fishermen. One man, Penghulu Awang Chik, described as a “weather-beaten, 41-years’-old fisherman who has spent more than a score [of] years on Singapore’s fishing ground”, was roped in to be an enumerator. In one week in May, he visited eight small islands and “accounted for 188 lonely island homesteads”.47

Because of the weather, travelling by sea could be challenging. Census supervisor T. Cordeiro had to carry out census work on Pulau Tekong. Unfortunately, just as he was about to leave the island, he was hit by a storm and his boat capsized. Fortunately, Cordeiro and five others in the party managed to hang on to their boat and they made their way safely back to Pulau Tekong.48

Counting the people living aboard vessels in the harbour required census officials to carry out their task between midnight and dawn. The enumerators – each supplied with a torchlight, a pencil, census forms, passes, and a set of instructions – were protected in the course of their duties by the police.

Malaya Tribune reporter Harry Fang accompanied the enumerators as they boarded the various vessels in the harbour and on the rivers. The night did not begin well for them though. The first vessel they boarded was the steamer Giang Ann. Fang said: “[W]e were half way through when a European member of the crew, apparently awaked in his sleep by the commotion, appeared in his pyjamas and created a small argument. Finally, we learned that the steamer’s crew had [already] been censused.”49

Naturally, most crew members did not react well to the appearance of Fang and company, given that they were awakened by enumerators “armed with torchlight, and escorted by policemen”.

Fang added that the “first reaction was always one of fear but after our explanation, the men became assured and readily supplied us with required information”. That said, getting the truth took time. “False names and ages were often given at first and after much gentle persuasion, the truth was finally told.”50

Conducting a census at sea had unexpected hazards as well, namely hardworking fisherman. “An old disinterested Chinese with his son fishing in a sampan off Beach Road nearly snared the Marine Police Chief, Mr J.W. Chiltern, when he cast his prawn net at the moment Mr Chiltern passed in one of his branch’s fast new launches.”51

This is not to say that census officials working in the city had an easy time. Some had to be given police escorts because as the Deputy Superintendent of the Census put it, in some parts of Singapore, “they would knock you on the head if you asked them their names”.52

Sometimes the census officials would get help from unexpected sources, as one newspaper story reported. “The Singapore Rubber Workers’ Union yesterday took time off from conducting a strike and a ‘squat’ to help the Deputy Superintendent of Census, Mr R.H. Oakeley, get census particulars from 120 recalcitrant workers”.53

The official report of the 1947 census – released in October 1949 – gave Singapore’s population as 940,824, which was almost double the figure for the 1931 census.54

Ang Seow Leng is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. Her responsibilities include managing the Singapore & Southeast Asian Collection, developing content as well as providing reference and research services related to Singapore and Southeast Asia.

Ang Seow Leng is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. Her responsibilities include managing the Singapore & Southeast Asian Collection, developing content as well as providing reference and research services related to Singapore and Southeast Asia.

Notes

-

Department of Statistics Singapore. (2019, October 1). Singapore Population. Retrieved from Department of Statistics Singapore website. ↩

-

United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Statistics Division. (2016). Handbook on the Management of Population and Housing Censuses. Retrieved from United Nations website. ↩

-

United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Statistics Division. (2019). Population and Vital Statistics Report (p. 1). Retrieved from United Nations website. ↩

-

McKeown, A. (2004, June). Global migration, 1846–1940. Journal of World History, 15 (2), p. 156. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Marriott, H. (1991). The peoples of Singapore: inhabitants and population. In Brooke, G.E., Makepeace, W. & Braddell, R. St. John, Sir. (Eds.). One hundred years of Singapore (p. 341). Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 ONE) ↩

-

Bastin, J. (2014). Raffles and Hastings: Private exchanges behind the founding of Singapore (p. 148). Singapore: National Library Board Singapore [and] Marshall Cavendish Editions. (Call no.: RSING 959.5703 BAS). According to Saw Swee Hock, “the enthusiasm of Raffles had led him to exaggerate somewhat” the population of Singapore. Thomas Braddell reported that the total population was 5,874 in 1821. See Saw, S. (2012). The population of Singapore (p. 8) (3rd Ed.). Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. (Call no.: RSING 304.6095957 SAW) ↩

-

Buckley, C.B. (1984). An anecdotal history of old times in Singapore 1819–1867 (p. 154). Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 BUC) ↩

-

Tables listing the figures for each of the early census from 1824 till 1911 are provided by Marriot from pages 355 to 362. Please note that census figures for years 1823 to 1828 can also be found in Singapore. (1829, February 12). The Singapore Chronicle and Commercial Register, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Papers of Thomas John Newbold. Retrieved from Archives Hub website. ↩

-

Newbold, T.J. (1971). Political and statistical account of the British settlements in the Straits of Malacca (Vol. 1, pp. 283–285). Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RCLOS 949.5 NEW) ↩

-

Saw, S. (1969, March). Population trends in Singapore, 1819_1967. Journal of Southeast Asian History, 10 (1), p. 36. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website; Untitled. (1871, March 15). Straits Times Overland Journal, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Straits Settlements. Government gazette. (1871, March 3). Government Notification No. 50. Singapore: Mission Press, p. 93. (Microfilm no.: NL1004) ↩

-

The legislative session. (1870, October 25). Straits Times Overland Journal, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Straits Settlements. Government gazette. (1870, October 21). Ordinance No. XI of 1870. An Ordinance for taking the Census of the Straits Settlements. Singapore: Mission Press, p. 607. (Microfilm no.: NL1004); Untitled. (1870, November 19). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Legislative Council. (1870, May 28). The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Straits Settlements. Government gazette. (1870, May 27). Speech of His Excellency Major General Sir Harry Ord, C.B., R.E., at the opening of the session of the Legislative Council of the Straits Settlements, on Monday, the 23rd May, 1870. Singapore: Mission Press, p. 148. (Microfilm no.: NL 1004) ↩

-

Straits Settlements. (1871). Blue book for the year (p. P8). Singapore: Government of the Colony of Singapore, Raffles National Library Archives. (Microfilm no.: NL2931) ↩

-

Saw, 2012, p. 339; Department of Statistics. (2019). Population trends 2019 (p. 37). Retrieved from Department of Statistics Singapore website. ↩

-

Vlieland, C.A. (1932). British Malaya (the Colony of the Straits Settlements and the Malay States under British protection, namely the federated states of Perak, Selangor, Negri Sembilan and Pahang and the states of Johore, Kedah, Kelantan, Trengganu, Perlis and Brunei): A report on the 1931 census and on certain problems of vital statistics (p. 9). London: Crown Agents for the Colonies. (Microfilm no.: NL3005) ↩

-

Del Tufo, M.V. (1949). Malaya, comprising the Federation of Malaya and the Colony of Singapore: A report on the 1947 census of population (p. 1). London: Published on behalf of the Governments of the Federation of Malaya and the Colony of Singapore by the Crown Agents for the Colonies. (Call no.: RCLOS 312.09595 MAL) ↩

-

Huff, G., & Majima, S. (Eds.; Trans.). (2018). World War II Singapore: The Chōsabu reports on Syonan (p. 3). Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.5703 WOR) ↩

-

Huff & Majima, 2018, pp. 133, 135. ↩

-

National Library Board. (2013). Operation Sook Ching written by Stephanie Ho. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia; Huff & Majima, 2018, p. 133. ↩

-

Census enumerators out tonight. (1947, August 23). The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Census has nothing to do with tax. (1947, March 7). The Singapore Free Press, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Saw, 2012, p. 341; Del Tufo, 1949, pp. 5, 158–160; Timeline of modern Singapore. (1999, December 31). The Straits Times, p. 37. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore census for 1957: 1,445,930. (1958, November 28). The Straits Times, p. 4; People of Singapore will be counted in 1957. (1956, April 27). The Singapore Free Press, p. 3; Pillay, T. (1957, February 1). Singapore census is set for June, 1957. Singapore Standard, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. (1969). Principles and recommendations for the 1970 population censuses. Second printing with changes of a non-substantive nature. Series M, No. 4. (p. 2). New York: United Nations. Retrieved from United Nations website. ↩

-

Arumainathan, P. (1973). Report on the census of population 1970, Singapore (p. 2). Singapore: Govt. Print. Off. (Call no.: RSING 312.095957 SIN); Sam, J. (1969, April 26). Census of S’pore next year: a $2.3 m. operation. The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Saw, 2012, p. 342. ↩

-

Saw, 2012, p. 343; Census to begin on May 20. (1980, May 14). The Business Times, p. 2; All set for the count. (1980, May 13). New Nation, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Republic of Singapore. Government gazette. Bills supplement. (1990, March 3). Census (Amendment) Bill (B 10/1990) (pp. 2–3). Singapore: [s.n.]. (Call no.: RSING 348.5957 SGGBS); Census officer can now swop information. (1990, March 29). The Straits Times, p. 18. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore. Dept. of Statistics. Census of Population Office. (1991). Census of population 1990: Advance data release (p. 2). Singapore: SNP Publishers. (Call no.: RSING 304.6021095957 CEN); 1990 census details to be released tomorrow. (1991, May 17). The Straits Times, p. 28. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Plans for Y2K census. (2000, February 29). The Business Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore Department of Statistics. (2002, June 19–21). Singapore’s new approach to census taking. At Conference on Chinese population and socioeconomic studies: Utilizing the 2000/2001 round census data. Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. Retrieved from United Nations Statistics Division website. ↩

-

Chuah, A. (2001, January 30). Minister pays tribute to chief statistician Paul Cheung. The Business Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Leow, B.G.; Singapore. Department of Statistics. (2002). Census of population 2000: Administrative report (pp. 6–7). Singapore: Dept. of Statistics, Ministry of Trade and Industry. (Call no.: RSING q304.6021095957 CEN) ↩

-

Singapore. Department of Statistics. (2011). Census of population 2010: Administrative report (pp. i, 6, 35, 50). Singapore: Dept. of Statistics, Ministry of Trade & Industry. (Call no.: RSING 304.6021095957 CEN) ↩

-

Coleman, D. (2012). Twilight of the census. Population and Development Review, 38, 334–351, pp. 334–335. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Leviathan’s spyglass. (2010, July 17). The Economist. Retrieved from Factiva via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Department of Statistics Singapore. (2019, October 4). Statistics Singapore Newsletter (Issue 2, 2019,p. 14). Retrieved from Department of Statistics Singapore website. ↩

-

Census count tomorrow. (1947, September 23). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Prizes for census enumerators. (1947, July 24). The Malaya Tribune, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Schoolboys to do S’pore census work. (1947, June 5). The Malaya Tribune, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Scouts to help census. (1947, August 16). The Singapore Free Press, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Four-fifths of rural Singapore already counted. (1947, May 25). The Sunday Tribune, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Sunday Tribune, 25 May 1947, p. 3. ↩

-

The Sunday Tribune, 25 May 1947, p. 3. ↩

-

Fisherman checks isles for census. (1947, May 11). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 11 May 1947, p. 7. ↩

-

Fang, H. (1947, September 24). Census men were asked: “Is this a raid?” The Malaya Tribune, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Malaya Tribune, 24 Sep 1947, p. 8. ↩

-

Census finds 1,000 homeless. (1947, September 25). The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Police escorts for census workers. (1947, September 24). The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore census winding up today. (1947, September 26). The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

S’pore doubles population in sixteen years. (1949, October 10). The Malaya Tribune, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩