Karikal Mahal: The Lost Palace of a Fallen Cattle King

William L. Gibson uncovers the story behind the pair of grand buildings along Still Road South and their transformation over the last century.

A rare colour photo of The Grand Hotel with its striking tower (building No. 26) taken by an unknown serviceman from RAF Changi before land reclamation works began, c. 1958. The round fountain pavilion where Moona Kader Sultan received his Legion d’Honneur is seen on the left. Courtesy of RAF Changi Association.

A rare colour photo of The Grand Hotel with its striking tower (building No. 26) taken by an unknown serviceman from RAF Changi before land reclamation works began, c. 1958. The round fountain pavilion where Moona Kader Sultan received his Legion d’Honneur is seen on the left. Courtesy of RAF Changi Association.

A stately, two-storey mansion stretches impressively along Still Road South in the eastern part of Singapore. On the opposite side of the busy, arterial road lies a no less spectacular building.

Now occupied by two preschools, these impeccably maintained structures are located on generous, manicured plots of land that were once just steps away from the sea. Some residents of the neighbourhood, however, will remember a time before land reclamation when these buildings looked very different.

Older residents will recall the presence of a third building on this massive plot of land, sitting between these two structures, that was bulldozed to make way for the construction of Still Road South when the government acquired part of the land in the early 1970s. The three buildings were collectively known as The Grand Hotel for a time.

The two remaining buildings on opposite sides of Still Road South was left derelict for more than a decade until the preschools took over the premises in 2016. For years rumours swirled about these abandoned buildings, and few knew that they were originally built as a private residence before becoming a hotel. Named Karikal Mahal, the buildings have played hosts to both high-society garden parties and illicit bedroom trysts for over a century. Karikal Mahal’s fascinating history is intertwined with stories of unimaginable wealth, allegations of murder and even feats of magic.

The Cattle King

Towards the close of World War I, successful Tamil Muslim businessman Moona Kader Sultan acquired a large plot of land not far from Telok Kurau.1 Formerly verdant coconut estates, the area was becoming a popular destination for seaside living, with bungalows and luxurious houses sprouting up among the palm trees as old plantation lands were sold off in small allotments in the area we now know as Katong. Although Kader Sultan owned many properties in Singapore, he chose this breezy seafront land to build a personal Shangri-La – which he named Karikal Mahal – a testament to his wealth and status as much as a monument to his business acumen or, as some would say, his folly.

Kader Sultan did not start out wealthy. Born in Karikal, part of France’s colonial possessions in India, he arrived in Singapore as a teenager in 1879 and started out as a moneychanger near the docks.2 He later claimed that at the time, the remuneration for his hard work was his “food and three dollars a month”.3

Witnessing the wealth being made by other Tamil Muslims in the cattle and sheep importation business, Kader Sultan turned his hand to the trade. Over the ensuing decades, he bought, bullied and buried rivals to his Straits Cattle Trading Company, which he had established with a handful of partners until he acquired the firm in 1914 to become the dominant cattle trader in Singapore.4 The press dubbed him the “Cattle King”, a title he held for the next 20 years. He was also one of the wealthiest men in Singapore then.

Kader Sultan soon became a prominent member of the Indian community in Singapore. He was one of the first members of the Mohammedan Advisory Board, created in 1915 to represent Muslim community interests to the colonial authorities. Four years later, he was named a Justice of the Peace.5

Kader Sultan was an avid football fan and established a football team for his company. For many years, he was President of the Malaya Football Association and launched the “Kader Sultan Cup”.6

Not forgetting his humble beginnings, Kader Sultan donated $10,000 to the Red Cross during World War I and a large amount to the Raffles College endowment fund, possibly over $20,000, during Singapore’s centenary in 1919.

He was loyal to his adopted home, noting in his speech to Muslim community leaders during the centenary that “living in a country which protects our persons, homes and hearths, and allows us privileges to practice our religion and customs as no other Government would do, we should contribute – the rich his thousands and the poor his mite – to make the Centenary a great success”.7

In 1923, Kader Sultan was issued with a Certificate of Naturalisation to honour his 45 years in the Straits Settlements.8 The highest accolade came in 1925 when he was made a Chevalier of the Légion d’Honneur. French Consul Andre Danjou presented Kader Sultan with the award at a garden party held on the grounds of his seaside Karikal Mahal home, an event covered not only in the local press but also in Paris by the weekly French newspaper L’Illustration.9 Singapore’s Cattle King had achieved international recognition.

But there was another side to the man. The livestock trade was a rough-and-tumble business and as Kader Sultan consolidated his position, rumours swirled of his nefarious dealings. As early as 1897, the Straits Cattle Trading Company was investigated for illegally exporting livestock.10 In 1906, in a case that dragged on for a year, the company was charged with supplying adulterated milk to hospitals.11

In 1920, the Commission on Profiteering launched investigations into profiteering and price-gouging by various cattle companies, including the Straits Trading Cattle Company.12 That same year, Kader Sultan’s name was prominently mentioned in relation to an attempted murder of a law clerk by mail bomb.13 In each instance, the Cattle King managed to stay above the fray, but the cut-throat nature of the livestock trade would eventually prove to be his undoing.

A Residence Fit for a (Cattle) King

On the land he bought in Katong, Kader Sultan developed a palatial estate for himself and his many wives, and one befitting his stature. He constructed three sprawling bungalows, one of which featured a three-storey tower, built in a mixture of late-Victorian, Italianate and Indian architectural styles, on adjoining plots of freehold land. Altogether, the land comprised a total 202,536 sq ft (roughly two-and-a-half football fields), not including adjacent lots he owned.14 The bungalows were connected by a neat square of walkways cutting through a sprawling garden. A fountain and fishpond were situated in the centre, surrounded by a circular pavilion. Just beyond the ornate seawalls, the surf rolled onto the beach.

Kader Sultan claimed that it cost him $500,000 to develop the site and build the bungalows. He named his lavish estate Karikal Mahal – Karikal (or Karaikal) being the town of his birth in southern India and Mahal meaning “palace” in Hindi and, perhaps with a wry sense of humour, also the Malay word for “expensive”.

In June 1930, the Singapore Municipal Commissioners approved the name Karikal Road for a private road between East Coast Road and Kader Sultan’s home. Two months later, the commissioners gave the name Karikal Lane to another parallel road between East Coast Road and Kader Sultan’s residence.15 (Running west of Karikal Lane, Karikal Road subsequently became part of Still Road South after land reclamation works in the 1970s.16)

Kader Sultan also owned the adjacent plots of land and on one of the lots fronting East Coast Road, he erected a bandstand and maintained the land as a football pitch and park for the community. The site was even used to host a travelling circus in October 1935.17

It is not clear exactly when Karikal Mahal was completed, although two dates have been suggested – 1920 and 1922.18 The earliest mention of it is found in newspaper reports from December 1922, when the “palatial residence” and grounds were used to host a farewell gathering for Captain A.R. Chancellor, the Inspector-General of Police, on his retirement and return to Europe.19 It was not the last high-society event that Karikal Mahal would host for a local luminary.

| THE INSPECTOR-GENERAL AND THE CATTLE KING |

| The closest we have to a biography of Moona Kader Sultan by someone who knew him is a brief description published 10 years after his death in a memoir by René Onraet, Inspector-General of the Straits Settlements Police from 1935 to 1939. |

| Onraet used the story of Kader Sultan to illustrate a point that “Asiatics” weave together “personal interests” with “loyalty to a higher cause” as a regular course of business. |

| The bulk of the sketch of Kader Sultan is a confessional conversation that the Cattle King shared with Onraet after his fall from grace in 1936. It paints the picture of a bitter, broken man. |

| Kader Sultan regretted the extravagance of Karikal Mahal. He said: “This house made living very expensive for me. The marriages of my sons from under its roof cost me a fortune. It has proved ‘mahal’ [expensive] indeed. Having to live up to it has helped to ruin me.” |

| As for the civic accolades he received, Kader Sultan was cynical. “In Karikal, I was persuaded to back some unknown man at the municipal elections, and later was awarded the Légion d’Honneur, as my candidate was elected! I think I got my J.P. [Justice of the Peace] in Singapore not only for being a leading Indian but for giving 10,000 dollars to the Red Cross fund in 1917. I also gave 20,000 dollars for Raffles College. The Government did not return these sums to me when they deprived me of my J.P.-ship.” |

| Onraet presents the quotes as though they were transcriptions of an actual conversation, but how accurate are the details? Did Onraet recall these words from memory? Did he embellish the story? We have no way of knowing. While this sketch appears to open a window into Kader Sultan’s final years, it must be taken with a pinch of salt. |

|

| Kader Sultan was declared bankrupt in 1936 after failing to pay his creditor just over $50,000. His Straits Cattle Trading company had shut down the year before. The Malaya Tribune, 9 January 1937, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. |

| REFERENCE |

| Onraet, R.H. (1947). Singapore: A police background (pp. 8–11). London: Dorothy Crisp and Co. (Not available in NLB holdings) |

In January 1930, the Muslim community threw a tea party in honour of Roland John Farrer, President of the Municipality – a position equivalent to Mayor of Singapore – on being made a Companion of the Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George. Farrer was highly regarded by the Muslim community for his work as Chairman of the Mohammedan Advisory Board and for lobbying to have Hari Raya Haji declared a public holiday. The band of the Johore Military Forces performed for over 1,000 guests and photographs of the event in the Malayan Saturday Post show long tables draped in white set in the garden of Karikal Mahal.20

Despite hobnobbing with high officials and the upper echelons of society, Kader Sultan’s cattle business was slowly unravelling. In the late 1920s, the livestock trade suffered a debilitating blow due to an outbreak of rinderpest and foot-and-mouth disease that severely restricted the importation of sheep and cattle.21

The beginning of the end came in early 1934 when Kader Sultan was implicated in a murder. Two of his employees had assaulted a man named Ferthal Khan, who worked for a rival cattle firm. Khan later died from his injuries. During court proceedings, the Cattle King denied ordering the assault. Although subsequently cleared of any wrongdoing, the scandal was hard to live down. Kader Sultan’s appointment as Justice of the Peace was revoked at the end of that year. In 1935, his Straits Cattle Trading Company shuttered permanently, and a year later he was declared bankrupt after failing to pay his creditor just over $50,000.22

Kader Sultan died in June 1937, aged 74, while visiting his hometown in India. He left behind six sons, five daughters and numerous grandchildren.23

Just before his death, Karikal Mahal was put up for sale at an auction to clear his debt. The property was valued at $150,000 but the highest bid received was $90,000.24 According to records at the Singapore Land Authority, the property was acquired in probate in 1938 by The Chartered Bank of India, Australia and China, a predecessor of today’s Standard Chartered. The buildings were emptied, but they would not stay vacant for long.

The Malayan Magic Circle

In August 1939, the Malayan Magic Circle located its new headquarters at Karikal Mahal. A branch of a British organisation founded in 1905, the Malayan Magic Circle started out in 1935 as a club for the settlement’s resident magicians. Proceeds from their performances were donated to charitable organisations and by 1939, they had disbursed over $25,000. They also put up free shows in hospitals and military barracks. 25 One of their most popular tricks was performed by founding member Armand Joseph Braga, a prominent lawyer and later Minister for Health under the David Marshall and Lim Yew Hock governments after the war. The trick involved Braga escaping from a full-sized coffin after being chained inside.

The Malayan Magic Circle most likely occupied the now-demolished building at 24 Karikal Road. The tenants were certainly happy in their new home, boasting of the “commodiousness” of the property in their newsletter, The Magic Fan, and noting that a “large and well-appointed stage” had been installed.26

The good times would not last long. By October 1941, with the war looming, the group decided to shutter its clubhouse due to gasoline rationing and members’ pressing wartime duties. But the club remained active, with performances at the Victoria Theatre and military garrisons to help boost wartime morale. It even staged a show on the night when the first Japanese bombs dropped on Singapore on 8 December 1941.27 The island fell two months later.

The Japanese Occupation

During the Japanese Occupation (1942–45), Karikal Mahal was appropriated by the Japanese military. Following the British surrender in February 1942, some members of the city’s European community were herded together on the Padang before being forced to march 8 km to Karikal Mahal, which had been transformed into a concentration camp surrounded by barbed wire. A pit latrine was dug on the beach where the D’Ecosia condominium is now located.

Within days, the internees started printing a camp newsletter produced by Australian Guy Wade and British-born Harry Miller, a former editor with The Straits Times, titled Karikal Chronicle.28

The men did their best to settle into what they thought would be their home for the next few years. Labour was divided, rules laid out and plans were made to plant the gardens. Props left behind by The Malayan Magic Circle were used to liven up the place. A library was created using books taken from the Kelly & Walsh bookstore (with the blessing of the manager), with the coffin from Braga’s escape act employed as an unconventional bookcase.29

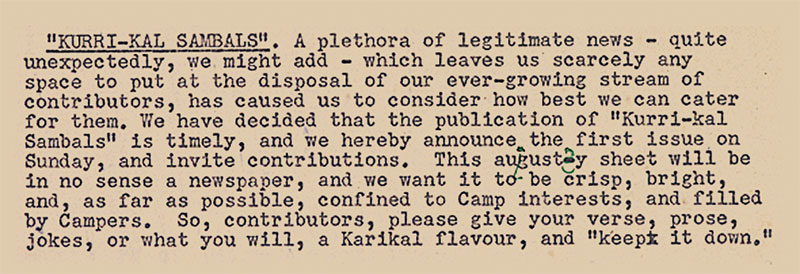

Nonetheless, the going was tough as food rations were often short. A standard joke was “I’m getting so thin I don’t know if I have stomach ache or back ache!”, but the men did their best to keep up their spirits. The Karikal Chronicle of 4 March 1942 announced a new light-hearted supplement titled Kurri-kal Sambals that would feature jokes and anecdotes of camp life with a “Karikal flavour”.30

Karikal Mahal was initially used as an internment camp for Europeans after the fall of Singapore in 1942. The prisoners began publishing a newsletter titled Karikal Chronicle and in its 4 March 1942 issue, announced plans for a supplement called Kurri-kal Sambals featuring jokes, prose and verse. However, the move to Changi Prison put paid to this plan. Retrieved from Cambridge University Library website.

Karikal Mahal was initially used as an internment camp for Europeans after the fall of Singapore in 1942. The prisoners began publishing a newsletter titled Karikal Chronicle and in its 4 March 1942 issue, announced plans for a supplement called Kurri-kal Sambals featuring jokes, prose and verse. However, the move to Changi Prison put paid to this plan. Retrieved from Cambridge University Library website.

However, the following day, a little over a fortnight after they first arrived, the Japanese announced that Karikal Camp would be vacated and the internees were marched to their new home in Changi Prison. The removal came as a shock but the editors of the Karikal Chronicle managed to put out an issue that day, scrawling “Special Edition” in pencil across the top.31 They would establish a sister paper, Changi Guardian, which they kept in print over the torturous years ahead.

The fate of the building throughout the Occupation years is unknown. After the war, the buildings remained vacant for several years as Singapore sought to recover from the terrible ordeal.

The Grand Hotel

In 1947, the Lee Rubber Company acquired the property along with the football field and an empty lot to the west. The company had been set up in 1931 by Lee Kong Chian, later Chairman of the Oversea Chinese Banking Corporation and Chancellor of the University of Singapore, and a highly respected philanthropist who established the Lee Foundation.32 Prior to the war, on the lot adjacent to Karikal Mahal, a road was laid and named Kuo Chuan Avenue, after Lee’s father, with quaint black-and-white bungalows built on either side.

The buildings of Karikal Mahal were renovated into a residential guest house called The Grand Hotel,33 which offered “seaside accommodation on reasonable monthly terms”, with “continental cuisine” and “new furniture”. Among its enticements was “Neptune’s Bar” serving “special Sunday tiffins”.34 The first European manager was replaced after a few years by James Tan, who would oversee the property for the next four decades.

An aerial photograph from 1958 shows The Grand Hotel and its tower (No. 26; bottom left of photo), as well as Nos. 24 and 25, with only some modifications from Kader Sultan’s time. The tower was demolished sometime in the 1960s. British Royal Air Force, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

An aerial photograph from 1958 shows The Grand Hotel and its tower (No. 26; bottom left of photo), as well as Nos. 24 and 25, with only some modifications from Kader Sultan’s time. The tower was demolished sometime in the 1960s. British Royal Air Force, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A map of the old Karikal Mahal estate, together with Nos. 24, 25 and 26, superimposed on a Google Maps image of the area today. Building no. 24 was torn down to make way for Still Road South. Land reclamation has also pushed the shoreline further south and much of Marine Parade now is built on reclaimed land.

A map of the old Karikal Mahal estate, together with Nos. 24, 25 and 26, superimposed on a Google Maps image of the area today. Building no. 24 was torn down to make way for Still Road South. Land reclamation has also pushed the shoreline further south and much of Marine Parade now is built on reclaimed land.

The field just north of the property remained an open space used by the neighbourhood kids for football matches and kite-fighting competitions.35

Newspaper advertisements from 1961 show one of the buildings nestled in a leafy garden; it had become an idyllic seaside retreat popular with servicemen from Changi Air Base.

The End of an Era

The beachfront oasis met an untimely end when land reclamation works began in 1966.36 The government mounted an ambitious modernisation campaign that included the reclamation of most of the southeastern coast of the island, with plans to build a new airport and a coastal highway leading to the city.

The massive reclamation project pushed the shoreline out, landlocking The Grand Hotel and replacing the seaside promenade with a busy thoroughfare – Marine Parade Road.

In anticipation of an interchange at Still Road leading into East Coast Parkway, Karikal Road was widened to accommodate increased vehicular traffic. The expansion bifurcated the property, obliterating the fountain, pavilion and walkways. Building No. 24 was demolished, and the remaining two structures isolated from one another by six lanes of a busy roadway. Towards the end of the decade, Karikal Road was renamed Still Road South.

A view of the now demolished building No. 24, 1967. It was torn down when the government acquired part of the land in the early 1970s to construct Still Road South. Lee Kip Lin Collection, PictureSG, National Library, Singapore..

A view of the now demolished building No. 24, 1967. It was torn down when the government acquired part of the land in the early 1970s to construct Still Road South. Lee Kip Lin Collection, PictureSG, National Library, Singapore..

By the early 1970s, it appears that The Grand Hotel limped on and was promoted as a 20-room budget hotel offering long-term rental packages at cheap rates. Its former grandeur lost, the place soon fell on hard times. In 1985, to keep the hotel afloat, long-time manager James Tan began charging a special rate of $50 for four hours of use, and the hotel soon developed a reputation as a destination for clandestine rendezvous.37

In 1993, The New Paper tabloid ran an exposé on “short time” love hotels in Katong, including The Grand Hotel. When interviewed, Tan, then 82, and living in the hotel, explained that business had declined during the 1970s and early 80s. To counter this, he introduced the new rate. “Now, the hotel is 80 percent full on the average. Business is good. Most of our income comes from these hourly bookings. On a good day, as many as six couples check into the hotel for a few hours… On weekdays, the hourly booking is more popular. During weekends, we have 100 percent occupancy, but most are here for a day.”38

Tan added there was one occasion when a woman stormed into the hotel with a private investigator and demanded to see her husband, who had booked a room to have a tryst with his mistress. Due to the ruckus created by the woman and her husband at the hotel reception, both were ordered to leave immediately.

Despite Tan’s best efforts, the hotel’s days were numbered. As the area became gentrified with luxury condominiums rising where seaside bungalows once stood, the seedy hotel became an embarrassment. In 2000, it lost its operating licence and closed down. The two buildings would spend the next 15 years lying vacant, slowly degrading from the humidity and the exhaust fumes from the increasingly busy road in front.

A New Chapter

In December 2003, the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) gave the building at 26 Still Road South conservation status under its “Conservation Initiated by Private Owners” scheme. This meant that the building could not be demolished and renovations had to be approved by the URA.39

In the meantime , the value of the property continued to soar. The Sunday Times noted in 2007 that the 60,000-square-foot plot of land at 25 Still Road South was valued at $300 million. Despite the eye-watering valuation, a representative of Lee Rubber said the company was using the building to store furniture. In 2009, the URA also granted conservation status to No. 25 under a new initiative for the creation of a Joo Chiat/Katong historical district, preserving what was left of Karikal Mahal. Lee Rubber, however, still had no plans for the two buildings at the time.40

A view of the still standing building No. 25 on Still Road South as it appeared in 1985. Lee Kip Lin Collection, PictureSG, National Library, Singapore.

A view of the still standing building No. 25 on Still Road South as it appeared in 1985. Lee Kip Lin Collection, PictureSG, National Library, Singapore.

It was only in 2016 that the buildings were given a new lease of life. Following a $5-million renovation, the two stately bungalows are now home to Odyssey The Global Preschool and Pat’s Schoolhouse Katong (at 25 and 26 Still Road South respectively), both operated by Busy Bees Asia which leased the buildings from Lee Rubber.41

The grounds of the two preschools are not open to the public but a wander around the site offers glimpses of the grandeur of the old estate. A portion of the original seawall still runs along Marine Parade, in front of No. 26. The football field on East Coast Road remains vacant, but greatly diminished in size due to road expansion works.

Pat’s Schoolhouse Katong now occupies one of Karikal Mahal’s buildings at 26 Still Road South. Courtesy of Willam L. Gibson.

Pat’s Schoolhouse Katong now occupies one of Karikal Mahal’s buildings at 26 Still Road South. Courtesy of Willam L. Gibson.

The initials “MKS” that were once emblazoned in a crest on the pediment above the main door of No. 25 no longer exist. The letterings were removed during the recent makeover, effectively erasing all traces of Moona Kader Sultan a century after he first built his Singaporean Xanadu. Karikal Lane is the only remaining vestige of the name that the Cattle King had given his palace.

| The author is continuing his research into Karikal Mahal and The Grand Hotel, and seeks photographs or stories about the site. Please contact him at cesasia21@gmail.com if you would like to help. |

Dr William L. Gibson is an author and researcher who has lived in Southeast Asia since 2005. His biography of the French journalist and explorer Alfred Raquez is forthcoming from Routledge. Learn more at www.williamlgibson.com.

Dr William L. Gibson is an author and researcher who has lived in Southeast Asia since 2005. His biography of the French journalist and explorer Alfred Raquez is forthcoming from Routledge. Learn more at www.williamlgibson.com.

NOTES

-

Lee Kip Lin claims Kader Sultan bought a plot of about 20 acres “between East Coast Road and the sea” in 1917. Lee, K.L. (2015). The Singapore house, 1819–1942 (p. 55). Singapore: Marshall Cavendish. (Call no.: RSING 728.095957 LEE). However, Lee cites no source and I could find no corroborating evidence for this date. Singapore Land Authority records for the property begin only in 1928. ↩

-

A. Muslim. (1937, June 9). Letters to the editor The late Mr. Kader Sultan. The Malaya Tribune, p. 20. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Onraet, R.H. (1947). Singapore: A police background (p. 9). London: Dorothy Crisp and Co. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Laffan, M. (2017). Belonging across the Bay of Bengal: Religious rites, colonial migrations, national rights (p. 108). New York: Bloomsbury Publishing. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

New advisory board. (1915, June 19). The Straits Times, p. 9; Untitled. (1919, January 9). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 23. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Boy scouts. (1919, April 1). The Malaya Tribune, p. 5; Malaya Football Association. (1919, November 21). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

How the Muslim community celebrated the Singapore Centenary. (1919, February 11). The Malaya Tribune, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Social and personal. (1923, August 25). The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Mr. K. Sultan honoured. (1925, March 9). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Une Fête Française a Singapour. (1925, April 25). L’Illustration, (4286), p. 414. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Illegal exportation of cattle. (1897, May 4). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser Weekly, p. 13. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Alleged adultration of milk. (1906, May 16). The Straits Times, p. 5; Adulterated milk. (1907, November 21). The Straits Times, p. 7; Adulterated milk. (1908, March 16). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Profiteering. (1920, November 27). The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Bukit Timah Road bomb outrage. (1920, October 28). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Page 2 Advertisements Column 4. (1936, November 11). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Municipal action. (1930, June 14). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 12; Singapore road names. (1930, August 12). The Straits Times, p. 20. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Savage, V.R., & Yeoh, B.S.A. (2013). Singapore street names: A study of toponymics (3rd ed.). Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions. (Call no.: RSING 915.957014 SAV-[TRA]) ↩

-

Harmston’s Circus comes to town. (1935, October 23). The Straits Times, p. 17. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Norman Edwards and Peter Keys claim the architect was the prolific Swan & Maclaren and provide two dates for the construction, 1920 and 1922. Edwards, N., & Keys, P. (1988). Singapore: A guide to buildings, streets, places (pp. 302–303). Singapore: Times Books International. (Call no.: RSING 915.957 EDW). However, they offer no source for their claim and seemed unaware that Moona Kader Sultan built the property. When contacted, Swan & Maclaren said they have no record of the site. ↩

-

Farewell to Captain Chancellor. (1922, December 11). The Straits Times, p. 8; Capt. A.R. Chancellor: Guest of the Mohammedan community. (1922, December 18). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 12; Hon. Capt. A.R. Chancellor. (1922, December 18). The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Mr Farrer feted. (1928, January 18). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 10; Mr. R.J. Farrer, C.M.G., entertained by the Muslim community. (1930, February 1). Malayan Saturday Post, p. 13. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Siddique, S., & Purushotam, N. (1982). Singapore’s Little India: Past, present, and future (p. 75). Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. (Call no.: RSING 305.89141105957 SID) ↩

-

Rivalry of livestock sellers revealed. (1934, February 9). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 3; The Gazette. (1934, December 4). The Straits Times, p. 16; Man who owed $51,306. (1936, February 22). The Malaya Tribune, p. 20. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Death of Cattle King. (1937, June 3). The Malaya Tribune, p. 13. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Affairs of millionaire. (1937, January 9). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 3; Bankruptcy of ‘Cattle King’. (1937, January 9). The Malaya Tribune, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Magic Circle. (1939, July 26). The Straits Times, p.14; Magic Circle Clubhouse. (1941, October 17). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Commentarium. (1939, October). The Magic Fan, 2 (2), 1. (Call no.: RRARE 793.8 MF; Accession no.: B32431654F) ↩

-

Magic Circle giving up clubhouse. (1941, October 17). The Malaya Tribune, p. 2; The clock didn’t stop. (1974, December 8). The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Archer, B. (2004). The internment of Western civilians under the Japanese, 1941–1945: A patchwork of internment (p. 105). London; New York: RoutledgeCurzon. (Call no.: R 940.53170952 ARC) ↩

-

University of Cambridge. (1942, March 3). Karikal Chronicle, 11. Retrieved from Cambridge University Library website. The entire Karikal Chronicle can be accessed online at https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-RCMS-00103-00012-00029. ↩

-

Karikal Chronicle, 12, 4 Mar 1942. ↩

-

Karikal Chronicle, 13, 5 Mar 1942. ↩

-

National Library Board. (2011). Lee Kong Chian written by Nor-Afidah Abd Rahman & Jane Wee. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website. ↩

-

Some online sources report the name as “Renaissance Grand Hotel”. This is an error. ↩

-

Page 2 Advertisements Column 4. (1947, September 27). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Merrilads Soccer. (1947, December 25). The Morning Tribune, p. 16. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Squire, T. (2019). Always a commando: The life of Singapore army pioneer Clarence Tan (pp. 86–88). Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions. (Call no.: RSING 355.0092 SQU). ↩

-

National Library Board. (2016). Marine Parade written by Alvin Chua. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website. ↩

-

Singapore Tourist Promotion Board. (1971). The hotels of Singapore (p. 3). Singapore: Singapore Tourist Promotion Board. Retrieved from BookSG; Page 23 Advertisements Column 3: Where to stay (S’pore). (1971, March 8). The Straits Times, p. 23; Hubby caught at hotel. (1993, January 8). The New Paper, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The New Paper, 8 Jan 1993, p. 7. ↩

-

Chan, C. (2004, November 13). Deserted but still grand. The Straits Times, p. 15. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Leow, V. (2007, April 22). Mitre Hotel owners sitting on another property goldmine. The Sunday Times, p. 6; Tay, S.C. (2009, January 17). Marked for preservation. The Straits Times, p. 93. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Lin, M., & Heng, J. (2016, July 31). New life for two grand dames. The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩