Let There Be Light

Timothy Pwee enlightens us about the history of street lighting in Singapore, starting with the first flickering oil lamps that were lit in 1824.

Lighted torches illuminating the evening sky as coolies transport coal to refuel a ship, c. 1876. Given the amount of fuel such torches consumed, it is not surprising that two years after this image was published, the first electric light began replacing torches. However, it would take several decades before electricity would light up many of the streets in Singapore. This illustration first appeared in The Graphic on 4 November 1876. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

Lighted torches illuminating the evening sky as coolies transport coal to refuel a ship, c. 1876. Given the amount of fuel such torches consumed, it is not surprising that two years after this image was published, the first electric light began replacing torches. However, it would take several decades before electricity would light up many of the streets in Singapore. This illustration first appeared in The Graphic on 4 November 1876. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

There is something special about Singapore at night. The glittering skyline of the Central Business District and Marina Bay is now an iconic image, while the annual festive light-ups of Orchard Road, Chinatown, Geylang Serai and Serangoon Road never fail to draw a crowd intent on taking selfies and wefies.

Singapore did not always sparkle after dark though. The first streetlights relied on feeble, flickering oil lamps, which were joined by gas-lit lamps in the second half of the 19th century. Even then, street lighting was limited to major areas in town. Streetlamps running on electricity were introduced in the early 20th century but there were not very many of these back then. It was only after World War II that the authorities came up with plans to ensure that all of Singapore’s streets would be lit at night.

The First Streetlamps

According to Charles Burton Buckley’s 1902 work, An Anecdotal History of Singapore, the first streetlamps in the settlement were lit on 1 April 1824, some five years after the British East India Company set up a trading post on the island. Oil lamps using coconut oil were installed on some bridges and major streets, at police tannah (police outpost or station) and on the facade of important buildings. While these lamps were an improvement over moonlight, there were problems. According to Buckley, “there were very few lamps and they had only a single glass in front, so the light was little use. As if to show this, Mr Purvis’s godown was broken into that same night and robbed of goods worth $500”.1

Indeed, the lamps themselves could become the targets of theft, as reported by the Singapore Chronicle in 1836:

“Last night the dwelling houses of both Messrs. Fraser and Guthrie, immediately adjoining each other, were entered by thieves. From the former all the hanging lamps in the upper verandah were taken away, and from the latter, only one lamp [left] hanging at the bottom of the stair-case, which they could not ascend from the door having been fortunately locked.”2

The lack of adequate street lighting meant that the “natives”, as locals were referred to by European residents, used torches with naked flames whenever they held night processions. This, of course, posed a fire hazard to buildings made of combustible materials such as wood and attap. In an 1833 letter to the editor of the Singapore Chronicle, the writer expressed concern after seeing a number of such processions during a walk around town:

“Last night I took a walk through the Town and in the course of my perambulations met no less than three or four processions of a similar kind… all of them carrying a greater or less number of torches, from which sparks were continually flying up into the air…”3

The poor lighting, combined with the absence of a proper police force in the early decades of colonial Singapore, contributed to the spate of violent crimes committed under the cover of darkness, as this account from the Singapore Chronicle in February 1832 demonstrates:

“[The] witness was awoke by a noise and perceived Chinese and witness’s companions fighting – also observed by the torches the Chinese brought, that the latter took away 7 boxes. Witness and his companions pursued, but he received a wound in the right arm. On returning observed that Bander and Bandarre, two of the crew had been killed and that the Nacodah of the prow likewise had received a wound….”4

It was only in 1843 that Singapore got its first fulltime police commissioner, Thomas Dunman. That same year, Maria Revere Balestier, wife of the first American consul in Singapore Joseph Balestier, donated a bell from her family’s Revere Foundry in Boston to St Andrew’s Church (subsequently demolished and replaced by St Andrew’s Cathedral in 1861).

As was typical in the largely unlit world of that era, Singapore was unsafe at night and had an after-dark curfew. One condition of Balestier’s gift was that the bell would be rung for five minutes every night, immediately after the firing of the 8 pm gun, to announce the start of curfew hours. This practice continued until 1874.5 (The bell currently resides in the National Museum of Singapore).

Aside from facilitating crime, the lack of street lighting also increased the chances of accidents, as a letter in The Singapore Free Press in July 1844 noted:

“I beg to suggest a remedy against broken legs of a dark night by the erection of two lamp Posts at the top of the Stairs. A bright idea that and no mistake! It would also be judicious to place lamps at each of the landing places, which would probably prevent the numerous accidents we hear of to parties leaving the steps on a dark night. It is not long since an unfortunate Commander of a vessel was drowned near the entrance of the river; now, Mr Editor, had there been a light the chances are his life might have been saved.”6

The landing places in question would have been located along the north bank of the Singapore River, in front of what is today the Asian Civilisations Museum. It seems that lamps were indeed installed after that letter was published, because in 1847, there was another letter complaining that the lamps had been removed when repairs were carried out at the Landing Place, causing people to miss their step and fall into the water:

“A few evenings since a Lady accompanied by her Husband, child and ayah nearly met with a very serious accident. They had alighted from a Palanquin and were proceeding to the landing place to embark in a Boat when the gentleman, who was in advance, not being aware of any steps, fancied he was still far from the water, and was in consequence precipitated to the bottom. The Lady unconscious of the danger was following, when a gentleman present caught her by the arm. The Ayah went a little to the left and fell amongst the loose stones but fortunately without injury to the child.”7

Detail from Charles Dyce’s The River from Monkey Bridge (ink and watercolour, 1842–3) showing a bridge lamp on the right. It would have been fuelled by coconut oil as this was before the introduction of gas lighting in Singapore in 1864. Image reproduced from Liu, G. (1999). Singapore: A Pictorial History, 1819–2000 (p. 31). Singapore: Archipelago Press in association with the National Heritage Board. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 LIU-[HIS]).

Detail from Charles Dyce’s The River from Monkey Bridge (ink and watercolour, 1842–3) showing a bridge lamp on the right. It would have been fuelled by coconut oil as this was before the introduction of gas lighting in Singapore in 1864. Image reproduced from Liu, G. (1999). Singapore: A Pictorial History, 1819–2000 (p. 31). Singapore: Archipelago Press in association with the National Heritage Board. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 LIU-[HIS]).

By 1849, it seems that lighting the town had become a priority, as the Municipal Committee decided to add “nearly 50 lamps, at a cost or lighting, of 300 dollars a year, exclusive of the first cost of lamps &c”.8

Merely adding a lamp did not necessarily mean there would be sufficient illumination as this complaint in The Singapore Free Press of 19 April 1850 attests:

“Most of the Public lamps are of no use whatever, through the dirt which covers them, and which prevents the rays of the light from passing through it. The lamplighters have no clean rags, employ very dirty ones, and have been seen using the water of the drains, that is to say muddy and dirty water, to clean these lamps. There is also a scarcity of lamplighters, it being sometimes pretty near Gun-fire before the lamps in some localities are reached.”9

Another problem was the tendency of some of these lamps to go out at night as this 1861 complaint in The Straits Times illustrates: “We call the attention of the Public Lamplighter to the fact, that the lamp at the corner of High Street and North Bridge Road, generally ceases to burn at One A.M.”10

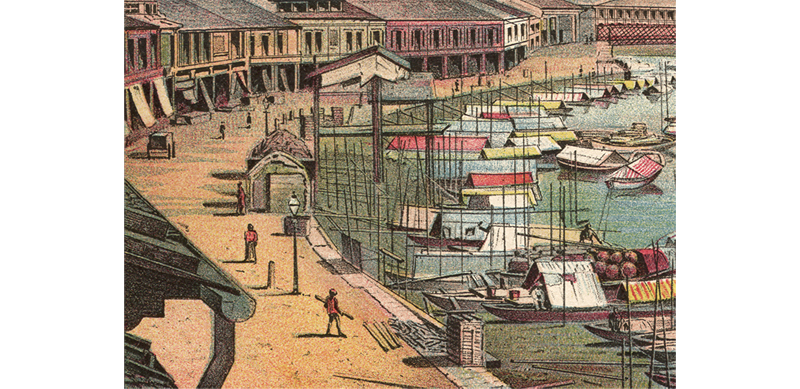

Detail from an illustration from the 1880s showing gas lamps along Boat Quay. The design of public lamps did not change much throughout the 19th century until the advent of electric lighting in the 20th century. Image reproduced from Moerlein, G. (1886). A Trip Around the World (p. 57). Cincinnati, Ohio: M. & R. Burgheim. Retrieved from BookSG. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Accession no.: B03351770D).

Detail from an illustration from the 1880s showing gas lamps along Boat Quay. The design of public lamps did not change much throughout the 19th century until the advent of electric lighting in the 20th century. Image reproduced from Moerlein, G. (1886). A Trip Around the World (p. 57). Cincinnati, Ohio: M. & R. Burgheim. Retrieved from BookSG. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Accession no.: B03351770D).

From Oil to Gas

While the fledgling town of Singapore was trying to get by with oil lamps, the big European cities of the 19th century were moving away from oil lamps to gas-lit lamps for street lighting. Cities in Europe had already embarked on gas lighting before Stamford Raffles arrived in Singapore in 1819. The Gas Light and Coke Company11 had been established in London in 1812 to supply gas for public use.

Installing gas-lit streetlamps around a city was no small matter though. Methane, the gas used for these lamps, had to be manufactured from coal and then distributed by an underground network of pipes to each lamp post. This meant that heavy investment was needed to build a gas production plant and to lay out a network of pipes connected to fixed lamp posts. The gas plant would also require a constant supply of coal. In addition, legislation would be needed to allow for the laying of underground pipes around the city.

In 1856, several acts were passed by the Legislative Council of India (known as the Indian Acts), which allowed for the appointment of municipal commissioners, granted powers of taxation and created a common legal structure for the municipal governments in Indian cities, including those in the Straits Settlements. These acts replaced a hodgepodge of older laws. In particular, the provisions of “Act XIV for the Conservancy and Improvement of the Towns of Calcutta, Madras, and Bombay, and the Several Stations of the Settlement of Prince of Wales’ Island, Singapore and Malacca” vested municipal commissioners with powers to contract and maintain street lighting. In the decade following this legislation, the cities under Indian administration, including Singapore, introduced gas streetlamps, something previously found only in the municipalities of Britain.

Robert Rigg, the first Secretary of the Municipal Commission, is credited as the driving force behind the introduction of gas lighting to Singapore.12 However, not much is known of his exact contribution, nor is it clear how or when the Singapore Gas Company – the firm behind the setting up of gas lamps here – was started. What is known is that there were negotiations from at least 1860 onwards about floating a company in London to build gasworks and piping in Singapore for street lighting. The company was officially registered in London in 1861, and a deal was subsequently struck for the company to supply a minimum of 400 gas lamps to the town of Singapore. The company also oversaw the construction of Singapore’s first gasworks, Kallang Gasworks,13 in 1862 to supply piped gas for street lighting.

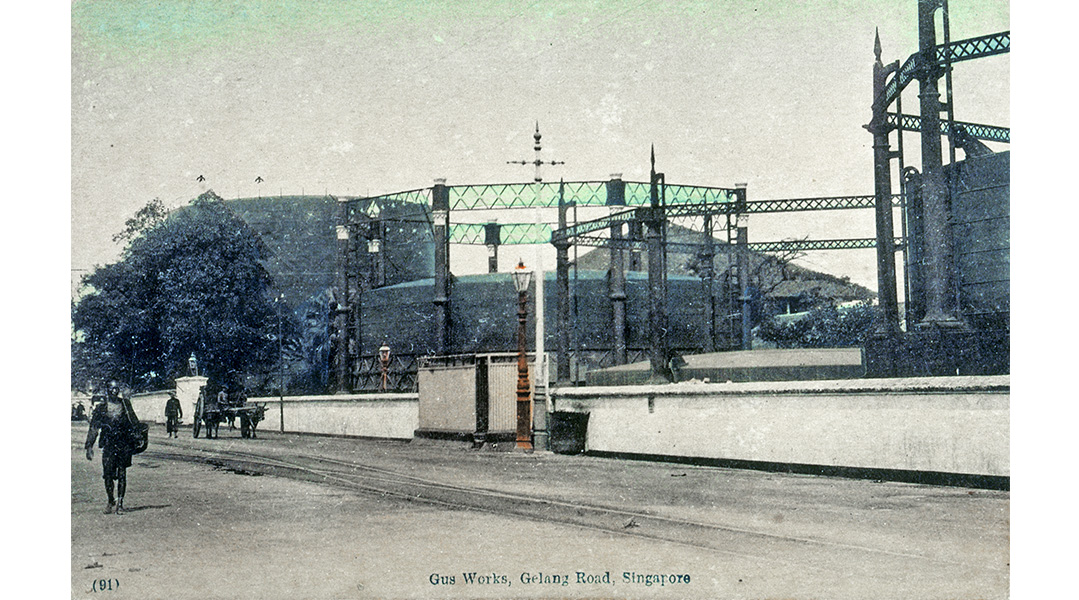

Singapore’s first gasworks, Kallang Gasworks, c. 1911. The gasworks was constructed in 1862 to supply the first piped gas for street lighting. It was decommissioned in March 1998 and its function taken over by Senoko Gasworks. Arshak C. Galstaun Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Singapore’s first gasworks, Kallang Gasworks, c. 1911. The gasworks was constructed in 1862 to supply the first piped gas for street lighting. It was decommissioned in March 1998 and its function taken over by Senoko Gasworks. Arshak C. Galstaun Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The gas lamps were first lit on the occasion of Queen Victoria’s birthday on 24 May 1864. People were supposedly so fascinated with the lamps that they were “seen going up to the lamp-posts and touching them gingerly with their finger-tips; they could not understand how a fire came out at the top without the post getting hot”.14 The Singapore Free Press reported that crowds “follow[ed] the lamplighter from lamp to lamp and gasp[ed] with astonishment and admiration as he produced light from nothing”.15

Why was a London-based company providing the infrastructure of streetlamps instead of a local one in Singapore? Aside from the engineering expertise being in London, there was also the large capital investment needed. At the time, Singapore did not have a capital market to raise the funds required.

The availability of gas lighting did not mean the end of oil lamps however. While the main thoroughfares were lit with gas, less important areas continued to rely on oil lamps. Interestingly, the new gas lamps were not lit during the full moon and the Municipal Council decided that oil lamps should be left unlit as well.16

The prevalence of street lighting gave life to the city, as a poem composed by 许南英 (Xu Nan Ying) in 1896, demonstrates:

“海山雄镇水之涯,商贾云屯十万家;

三岛千洲人萃处,此坡合好号新嘉.

傍晚齐辉万点灯,牛车水里闹奔腾;”17

[Translation]

“Sea and mountain meeting at the shore,

A multitude of businesses gather;

Where people of a thousand lands meet,

‘Singapore’ is the name of this town.

Ten thousand lamps light up the evening,

Kreta Ayer bustles with life;”

A gas lamp along Geylang Road, c. 1900s. Lim Shao Bin Collection, PictureSG, National Library, Singapore.

A gas lamp along Geylang Road, c. 1900s. Lim Shao Bin Collection, PictureSG, National Library, Singapore.

The Advent of Electric Lighting

Electric lamps only started appearing on Singapore’s streets from the early 20th century, although electricity had been used for indoor lighting from as early as the 1880s.

Cities in the United States first began using electric arc lighting in the 1870s, despite its light being too glaring. Electric arc lighting involved placing two carbon electrodes slightly apart but close enough for an electric spark to form between the two electrodes, emitting a brilliant arc. So brilliant was the light that one of the earliest records of its use was by the British Navy as searchlights mounted on ships. Not everyone appreciated being spotlit though, as this irate-sounding letter in The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser Weekly Mail Edition in 1890 illustrates:

“A great inconvenience could be very easily abolished if the Royal Engineers on Pulau Brani would, in their electric searchlight practice, avoid choosing the exact time and neighbourhood of the departure of mail steamers. It is a physical impossibility to pilot a vessel safely in the face of the blinding glare of the electric light.”18

Another downside was that the open arc was a potential fire hazard, which precluded it from being used indoors.

The Tanjong Pagar Dock Company installed an electric arc light in July 1878; the Siemen’s arc lamp emitted light equivalent to about 2,000 candles “to facilitate work which had to be carried on all night”.19

In February 1885, the Telegraph Office in Singapore installed 59 Edison-Swan incandescent bulbs. These bulbs worked by heating a filament in a vacuum to produce light. The following year, the Union Hotel on Hill Street replaced its gas burners with electric lamps, using incandescent bulbs of either 16 or 32 candlepower each (around 20 to 40 watts ).20 In 1890, Government House (now known as the Istana) was also fitted with incandescent lamps.21

Using such bulbs for street lighting, however, took longer. While the owners of individual buildings could install a small generator to power their own lights, a system of electric street lighting – which was more complex – necessitated an electrical power station, in the same way that gas lighting required a central gasworks.

The impetus was the introduction of the electric tram system in Singapore, which led to the setting up of the city’s first electrical power station. In 1901, the Singapore Tramways Ltd was founded in London, and work on the power station and headquarters at MacKenzie Road in Singapore began the following year. The power station began generating electricity in 1905 and the first regular tramway route started running on 25 July the same year. The power station also supplied the electricity required for electric street lamps, which were first used in 1906 to light up Raffles Place and the Esplanade (now Padang).

Singapore’s first electrical power station on Mackenzie Road, 1905. It generated electrical power for the trams and also supplied the electricity for electric street lamps, which were first installed in 1906. F.W. York Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Singapore’s first electrical power station on Mackenzie Road, 1905. It generated electrical power for the trams and also supplied the electricity for electric street lamps, which were first installed in 1906. F.W. York Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Electricity quickly penetrated society, used in government offices, commercial buildings and homes. The Tanjong Pagar Dock even started its own power plant to electrify operations in 1909. Singapore’s increasing electricity demand led to the opening of a second power station, St James Power Station,22 in 1927.

A major power failure on the evening of 16 April 1936 showed how dependent Singapore had become on electricity, with cookers and refrigeration shutting down and cinemas cancelling screenings. Even Government House was not spared, and Governor Shenton Thomas “had to ‘feel’ his way round the passages until peons arrived with electric torches”. The Singapore Free Press reported that a “feature of the ‘black-out’ was the revelation that about seven-eighths of the streets of Singapore, claimed to be one of the most modern cities of the East, are still gas-lit”.23

In November 1936, a Straits Times editorial claimed that Singapore had “some of the worst lighted streets in the world”, and the obsolete and old-fashioned gas street lamps provided poor lighting for motorists and pedestrians.24 T.H. Stone, President of the Singapore Rotary Club, echoed this view. In a Rotary luncheon in September 1937, he said “[t]he complete overhaul of Singapore’s lighting is necessary and urgent because there is not a single street in this island that is properly lit”.25

The rise of the automobile was the reason for the sudden disaffection with gas streetlamps. Poorly lit streets made the darkness between gas lamps dangerous blind spots for drivers.

In the early 1930s, there was a further development of the electric arc lamp. By sealing the lamps in tubes of sodium or mercury vapour to create a bright glow, it made “perpetual daylight” possible as one enthusiastic 1933 report in The Straits Times put it.26 By 1937, both Kuala Lumpur and Ipoh had installed test stretches of mercury vapour lamps with positive results.27 Singapore did its own test along East Coast Road between Katong and Siglap with 300-yard stretches lit up by mercury vapour, sodium vapour and standard electric filament lamps.28

In December 1937, a committee was set up to look into traffic problems in Singapore and to recommend solutions.29 The report, produced the following year, noted that poor street lighting was one of the causes of traffic accidents and proposed lighting standards for the various classes of streets. The most important routes were classified as Group A, and only mercury or sodium vapour lamps were deemed suitable for these roads. The dozen highway routes included the main thoroughfares in town such as Beach Road, Orchard Road and Connaught Drive as well as major routes outside of town, like Clemenceau Avenue, Kallang Road, Bukit Timah Road, Thomson Road and Serangoon Road.30

The lighting recommendations, however, were not accepted by the Municipal Commission who proceeded with its own lighting plans and street classification system. In 1940, it successfully lit a stretch of Clemenceau Avenue using mercury vapour lamps but further plans were derailed due to the war.31

At the start of the Japanese Occupation (1942–45), the Japanese Military Administration took the opportunity to repair the damage caused by the war by replacing street lighting at 43 major junctions in Singapore with electric street lighting.32

The immediate post-war years saw Singapore’s population swelling to over 900,000 due to people being displaced from Malaya and the surrounding region. The resulting demand, which saw a sharp increase in the use of gas plus the difficulty of getting replacement gas lamps, hindered repair and servicing work.

In December 1946, the Municipal Commission approved a $30,000 budget to install 72 electric lamps at various strategic locations in the city, such as Victoria Street, Bras Basah Road, River Valley Road and Outram Road as an initial measure.33 In 1947, a proper five-year scheme costing $1 million was implemented to install more than 3,000 electric street lamps in Singapore. This was followed in July 1951 by a second five-year plan amounting to $1.5 million to improve street lighting.34

Overhead electric tram lines and an electric lamp along High Street, early 20th century. Lim Shao Bin Collection, PictureSG, National Library, Singapore.

Overhead electric tram lines and an electric lamp along High Street, early 20th century. Lim Shao Bin Collection, PictureSG, National Library, Singapore.

In 1954, the City Council (successor of the Municipal Commission) announced that the approximately 530 gas street lamps still in use in Singapore would be scrapped by the end of the following year and replaced with electric lamps.35

Whether in 1955 or a little later, the complete crossover to electric bulbs would have put Singapore’s 25 lamp attendants out of work. By the late 1940s, time switchers had replaced the lamplighters, who previously did their rounds in the evening to light the gas lamps and then returning in the morning to extinguish them.36 However, while lamp lighting was no longer needed, the lamps still needed cleaning and maintenance. This was a job handled by the lamp attendants employed by the Gas Department.

While electric lamps were brighter and cheaper, there was, however, one important task that gas lamps excelled at that electric lamps could not accomplish – concealing bad smells. In 1955, about a dozen gas lamps around Singapore were kept burning day and night, supposedly to “offset the smell which might otherwise escape from the sewage mains near which they were installed”, according to City Councillor Chan Kum Chee.37 These gas lamps were located in places such as the Telok Ayer police station, Fort Canning and the Immigration Office.

By the 1960s, thanks to widespread electrification, Singapore glowed at night. Songs were even written about how beautiful Singapore was after dusk. The 1962 P. Ramlee movie Labu dan Labi, a comedy about two bumbling servants, features the song “Singapura Waktu Malam”, a paean to Singapore at night. The opening stanza goes:

“Singapura waktu malam

Lampu neon indah berkilauan

Gedung tinggi gemerlapan

Sungguh megah tiada bandingan”

[Translation]

“Singapore at night

Neon lights beautifully sparkling

Glittering tall buildings

Really magnificent without compare”

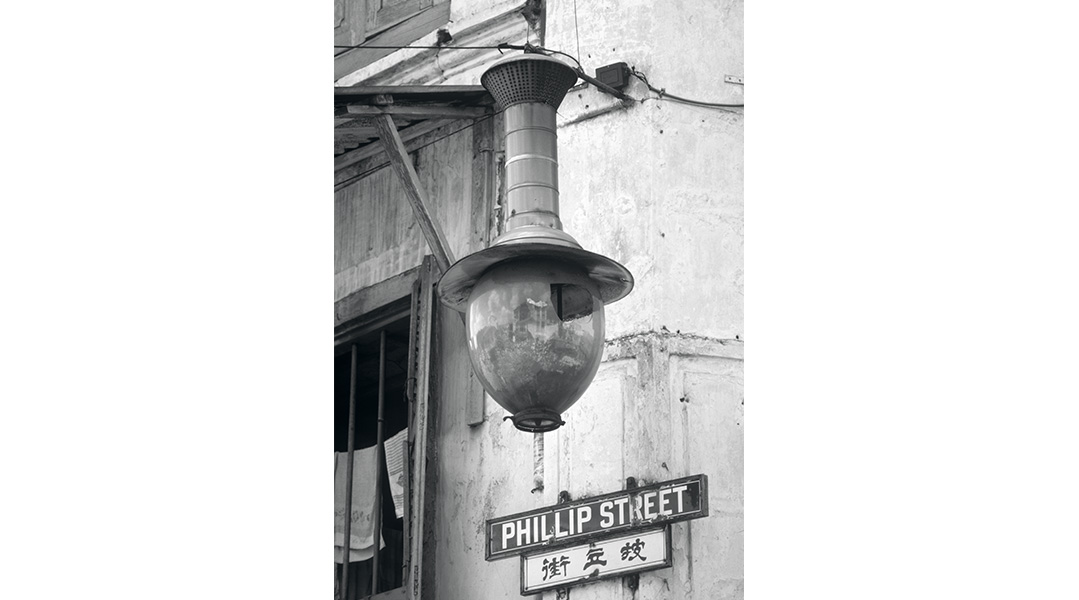

The bulb of this street lamp along Phillip Street photographed in 1968 resembles the ones from early 20th-century Singapore. Lim Shao Bin Collection, PictureSG, National Library, Singapore.

The bulb of this street lamp along Phillip Street photographed in 1968 resembles the ones from early 20th-century Singapore. Lim Shao Bin Collection, PictureSG, National Library, Singapore.

| Assistance for the English translations of the Chinese poem by 许南英 and the Malay song by P. Ramlee were provided by colleagues Goh Yu Mei and Juffri Supaat respectively. |

Timothy Pwee is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. He is interested in Singapore’s business and natural histories, and is developing the library’s donor collections around these areas.

Timothy Pwee is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. He is interested in Singapore’s business and natural histories, and is developing the library’s donor collections around these areas.

NOTES

-

Buckley, C.B. (1902). An anecdotal history of old times in Singapore (Vol. I; p. 155). Singapore: Fraser & Neave. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.57 BUC) ↩

-

Singapore. (1836, May 14). Singapore Chronicle, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Correspondence. (1833, May 30). Singapore Chronicle, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore. (1832, February 2). Singapore Chronicle, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Balestier bell finds a home. (1937, October 17). The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Correspondence. (1844, July 24). The Singapore Free Press, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Free Press. (1847, August 12). The Singapore Free Press, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Free Press. (1849, February 22). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Local. (1850, April 19). The Singapore Free Press, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Untitled. (1861, January 12). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Gas Light and Coke Company, headquartered in Westminster, London, made and supplied coal gas and coke. It was the first company set up to supply London with coal gas and operated the first gasworks in the United Kingdom, which was also the world’s first public gasworks. ↩

-

Untitled: Gas for Singapore. (1861, August 17). The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Kallang Gasworks was decommissioned in March 1998 and its function taken over by Senoko Gasworks. See Tan, B. (2018). Kallang Gasworks. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia, National Library, Singapore. ↩

-

Makepeace, W., Brooke, G.E., & Braddell, R.S.J. (1921). One hundred years of Singapore: Being some account of the capital of the Straits Settlements from its foundation by Sir Stamford Raffles on the 6th February 1819 to the 6th February 1919 (Vol. II; p. 512). London: John Murray. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.51 MAK-[RFL]) ↩

-

Groom, P. (1957, October 21). Crowds worshipped the ‘miracle’ lamplighter. The Singapore Free Press, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Municipal Council. (1864, July 9). The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

饶宗颐 [Rao, Z.Y.]. (1994).《新加坡古事记》(pp. 283–284). 香港: 中文大学出版社. (Call no.: Chinese RSING 959.57 JTI) ↩

-

Untitled. (1890, October 8). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser Weekly Mail Edition, p. 399. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The electric light in the Straits Settlements. (1886, November 22). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The first installation of the electric light in Singapore. (1886, April 3). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Electric light at Government House. (1890, February 25). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Nuradilah Ramlan & Neo, T.S. (2017). St James Power Station. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia, National Library, Singapore. ↩

-

Great black-out in Singapore. (1936, April 17). The Singapore Free Press, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Move to better Singapore’s street lighting. (1936, November 22). The Straits Times, p. 15. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Strong criticism of Singapore’s lighting. (1937, September 30). The Singapore Free Press, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Daylight at night on British roads. (1933, August 3). The Straits Times, p. 17. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Around Malaya. (1937, March 24). The Malaya Tribune, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Important street lighting plan started in Singapore last night. (1938, September 3). The Malaya Tribune, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Committee will investigate city traffic problems. (1937, December 1). The Singapore Free Press, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Trimmer, G.W.A. (1938). Traffic conditions in Singapore, 1938 (pp. 18–25). Singapore: Government Printing Office. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

Singapore relighting scheme postponed. (1940, March 2). The Singapore Free Press, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Syonan to have better type street lights. (1942, July 14). Syonan Shimbun, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

More street lights at strategic points. (1946, December 18). The Malaya Tribune, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Lights for 86 miles of road. (1951, July 7). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

A brighter S’pore soon: Gas yields to power. (1954, June 1). The Singapore Free Press, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Time and the lamplighter. (1948, June 13). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Lamps that are never put out. (1955, March 21). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩