Raffles Displaced

Raffles, once widely admired and revered as the founder of Singapore, has been portrayed in a more complicated light in recent years, as Ng Yi-Sheng tells us.

Raffles’ “Disappearance” by Teng Kai Wei in partnership with the Singapore Bicentennial Office. On 31 December 2018, the polymarble Raffles statue along the Singapore River was painted over to give the optical illusion that it had been removed. Courtesy of the Singapore Bicentennial Office.

Raffles’ “Disappearance” by Teng Kai Wei in partnership with the Singapore Bicentennial Office. On 31 December 2018, the polymarble Raffles statue along the Singapore River was painted over to give the optical illusion that it had been removed. Courtesy of the Singapore Bicentennial Office.

On 7 June 2020, as the Black Lives Matter protests raged around the world, a group of anti-racism activists in Bristol toppled a statue of the 17th-century slave trader Edward Colston, rolled it all the way to the harbour, and then triumphantly dumped it into the Avon River.

This act galvanised activists across the globe. In Brussels, people began defacing sculptures of the murderous King Leopold II. In Boston and St Paul, statues of Christopher Columbus were attacked while in Penang, a Francis Light statue was vandalised with red paint.

Meanwhile, in Singapore, satirical Twitter account @Raffles_Statue reposted a video of the Colston statue being dropped into the harbour, with this comment:

“I’d like to declare that I can’t swim. #StatueLivesMatter”1

This was just one of many voices in mid-2020 urging Singaporeans to consider the removal of the statue of Stamford Raffles. Dhevarajan Devadas, a research assistant at the Institute of Policy Studies, posted on Facebook that we should “finally acknowledge the impact of colonialism on the indigenous people of this region by vacating his place of honour”.2 Veteran journalist Jeevan Vasagar agreed, writing in a column for the Nikkei Times that “Raffles should disappear for good”.3

An engraving of Stamford Raffles by James Thomson, 1824. National Portrait Gallery, London. Image reproduced from Boulger, D.C. (1897). The Life of Sir Stamford Raffles. London: Horace Marshall & Son. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Accession no.: B03013459C).

An engraving of Stamford Raffles by James Thomson, 1824. National Portrait Gallery, London. Image reproduced from Boulger, D.C. (1897). The Life of Sir Stamford Raffles. London: Horace Marshall & Son. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Accession no.: B03013459C).

How did this revolt against Raffles arise? One major stimulus was the publication of Tim Hannigan’s Raffles and the British Invasion of Java (2012).4 This non-fiction work details how Raffles instigated the British East India Company’s bloody invasion and subsequent occupation of Java between 1811 and 1815, ritually humiliating the royals and pillaging their treasure houses, and mismanaging funds and alienating his colleagues. He even allowed the local Javanese to be kidnapped for slavery, including sexual bondage, for his friend Alexander Hare’s colony in Banjarmasin, on the island of Borneo.5

Criticisms mounted with Nadia Wright’s William Farquhar and Singapore: Stepping out from Raffles’ Shadow (2017),6 which claims that the credit for establishing the port of Singapore should in fact go to the first Resident, William Farquhar, rather than Raffles, who spent a mere eight months on the island. Then in 2019, the Asian Civilisations Museum’s exhibition titled “Raffles in Southeast Asia – Revisiting the Scholar and Statesman” highlighted how his writings on Southeast Asia were rife with plagiarism and misinterpretation of evidence.

Artists and playwrights have been inspired by these polemics. Jimmy Ong, for instance, has created numerous artworks that depict Raffles being punished for his sins. In his charcoal drawing Roro Rafflesia (2015), Raffles is stripped naked and scolded by a Javanese goddess. In his performance installation Open Love Letters (2018), Raffles’ headless and legless body is sawn in half and used as a charcoal grill to make biscuits known colloquially as “love letters”.

Haresh Sharma’s play Civilised (2019) imagines Raffles and Farquhar still alive in the present day, collaborating as oppressors. Alfian Sa’at and Neo Hai Bin’s documentary theatre production Merdeka / 獨立 / சுதந்திரம் (2019) features re-enactments of key events in Singapore’s history, including Raffles’ callous treatment of Sultan Husain Shah in Singapore and the royal family in Yogyakarta.7

The 2019 theatre production of Merdeka / 獨立 / சுதந்திரம் by Alfian Sa’at and Neo Hai Bin re-enacts key events in Singapore’s history, including Stamford Raffles’ callous treatment of Sultan Husain Shah in Singapore and the royal family in Yogyakarta. Courtesy of of W!ld Rice.

The 2019 theatre production of Merdeka / 獨立 / சுதந்திரம் by Alfian Sa’at and Neo Hai Bin re-enacts key events in Singapore’s history, including Stamford Raffles’ callous treatment of Sultan Husain Shah in Singapore and the royal family in Yogyakarta. Courtesy of of W!ld Rice.

These revisionist depictions of Raffles represent only the latest in a series of cultural movements, all grappling with a figure who has loomed large over popular history in Singapore. Over the past two centuries, dozens of artists and intellectuals have invoked his name to further their own agendas. Taken as a whole, their works reveal the complex and continually shifting relationship between Singapore society and the legacy of colonialism.

Raffles Instituted (1817–1942)

The earliest artworks associated with Raffles arose not out of victory, but abject failure. In 1815, he was dismissed from Java, having failed to make the colony profitable for the East India Company. Back in London, he took pains to restore his reputation. In 1817, he wrote and published The History of Java8 and commissioned portraits of himself by George Francis Joseph and James Lonsdale, a marble bust by sculptor Francis Leggatt Chantrey, a miniature by Alfred Edward Chalon as well as a coat of arms to commemorate his knighthood.

Plaster cast of Francis Leggatt Chantrey’s bust of Stamford Raffles. Bastin Collection, National Library, Singapore. (Accession no.: B29029424J).

Plaster cast of Francis Leggatt Chantrey’s bust of Stamford Raffles. Bastin Collection, National Library, Singapore. (Accession no.: B29029424J).

Raffles died in 1826, bankrupt. It was his widow, Lady Sophia Raffles, who took on the task of rehabilitating her husband’s image, with considerably more success. In 1830, she published his papers under the title, Memoir of the Life and Public Services of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles,9 and even convinced Chantrey to erect a life-size marble statue of him at Westminster Abbey in 1832, which still stands today. She also commissioned multiple copies of Chantrey’s bust of Raffles, including one that she sent to Singapore.10

Raffles soon won further acclaim in Singapore, thanks to the writer Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir, better known as Munsyi Abdullah. In 1849, he published Hikayat Abdullah (Stories of Abdullah), a memoir containing anecdotes of early Melaka and Singapore, including the time he worked as Raffles’ scribe.11 Here, the latter is praised in the most glowing of terms. Two poems celebrate Raffles and his wife, and the author writes, “Even should I die and return to this world in another life I should never again meet such a man.”12

However, the cult of Raffles only really gained momentum in the latter half of the 19th century as his name began to be attached to numerous landmarks in Singapore: Raffles Lighthouse in 1855, Raffles Place (formerly Commercial Square) in 1858, Raffles Institution (formerly Singapore Institution) in 1868, Raffles Library and Museum (formerly the Singapore Library) in 1874 and Raffles Hotel in 1887.

These efforts culminated in the bronze statue by the famed British sculptor-cum-poet Thomas Woolner portraying Raffles as a pillar of imperial might, eight feet tall on his pedestal, arms confidently folded, one foot trampling on a map of Singapore. This was unveiled at the Esplanade (now Padang) on 27 June 1887 to serve as “a permanent memorial of the Jubilee”,13 i.e. the 50th anniversary of Queen Victoria’s coronation.

Before the grand opening, Inspector of Schools A.M. Skinner held a competition for the best inscription to accompany the statue. One finalist was Raffles Institution schoolboy D.C. Perreau, who penned the following lines:

An Epitaph

Immortal founder of this isle,

Thy work is done and yet no smile

Comes from thy cold but pensive face

To greet the glory of the place

Which eight and sixty years ago

Thy weary wand’rings well did know;

Ope but a while thy closéd eyes

And see the perfect paradise

Thy restless once, now folded, arms

Have placed amidst Earth’s fairest charms

In vain we ask; Life’s spark no more

Doth shine as it had done before;

Thou’rt gone, great soul, thou’rt gone, but thou,

Though dead, art not forgotten now!

Labor Omnia Vincit14

In the end, however, the final inscription was somewhat more prosaic:

“On this historic site, Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles first landed in Singapore on 28th January 1819, and with genius and perception changed the destiny of Singapore from an obscure fishing village to a great seaport and modern metropolis.”

Why was Perreau’s more poetic text not chosen? One possible reason is that it speaks of the death of the colonist. The British had no desire to mourn Raffles the man – instead, they wanted to glorify his lasting accomplishments.

In the years that followed, the statue suffered a number of indignities. During sports events at the Esplanade, it was hit by stray footballs and clambered upon by spectators, seeking better views.15 For this reason, the statue was moved to its current location in front of the Victoria Memorial Hall at Empress Place, as part of the centenary celebrations in 1919, accompanied by Doric columns, a marble-lined pool, fountain jets and vases of flowers.

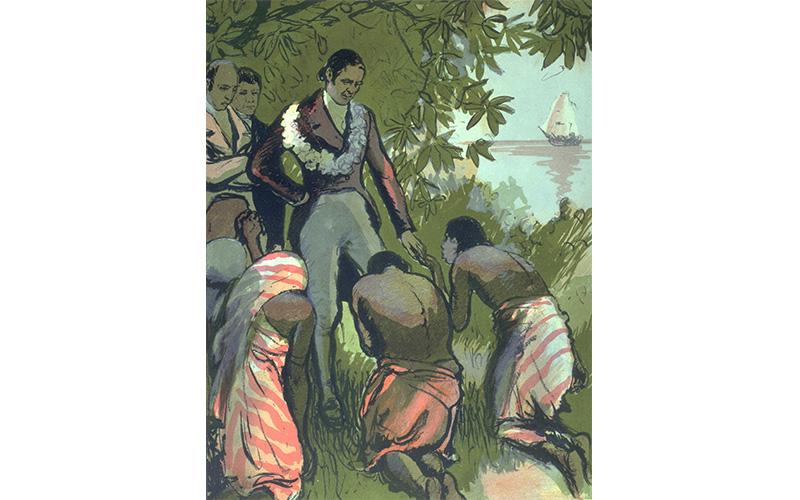

Meanwhile, Raffles’ image proliferated in other media. In a 1927 poster produced for the Empire Marketing Board,16 Raffles stands alongside other colonists such as James Cook17 and Cecil John Rhodes18 in a group portrait. He also appears in The Pageant of Empire: An Historical Epic, held at the Empire Stadium (now Wembley Stadium) in London in 1924.19 The souvenir volume features an illustration titled Singapore: Stamford Raffles’ Farewell by Gerald Spencer Pryse, which shows a garlanded Raffles with local men and women kneeling before him as if in worship.

Artwork of Singapore: Stamford Raffles’ Farewell by Gerald Spencer Pryse, 1924. It shows a garlanded Stamford Raffles with local men and women kneeling before him as if in worship. The illustration appears in the souvenir volume for The Pageant of Empire: An Historical Epic held in London in 1924. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Artwork of Singapore: Stamford Raffles’ Farewell by Gerald Spencer Pryse, 1924. It shows a garlanded Stamford Raffles with local men and women kneeling before him as if in worship. The illustration appears in the souvenir volume for The Pageant of Empire: An Historical Epic held in London in 1924. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Raffles Reconstituted (1942 onwards)

World War II put an end to the myth of British invincibility. During the Japanese Occupation of Singapore (1942–45), amid rumours that the bronze statue of Raffles would be melted down for the metal, it was quickly removed and stored in the former Raffles Library and Museum (renamed Syonan Library and Museum during the Occupation). When the statue was reinstalled at Empress Place after the war, it was stripped of its colonnade, which had been damaged by bombing, and its flower vases were lost for good.

In the post-war years, there were some signs that the cult of Raffles might be on the wane. In 1949, Raffles College merged with King Edward VII College of Medicine, rebranding itself as the University of Malaya. In 1960, the Raffles Library was renamed the National Library.

In 1960, the Dutch economist Albert Winsemius arrived in Singapore as a consultant to the Singapore government. He told then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew that there were “two pre-conditions for Singapore’s success: first, to eliminate the Communists who made any economic progress impossible; and second, not to remove the statue of Sir Stamford Raffles”.20 Both these acts, he argued, would show Western capitalist nations that Singapore still welcomed their investments.

Lee embraced this advice. In 1969, at the opening of an exhibition to mark the 15th anniversary of the People’s Action Party (PAP), then Minister for Foreign Affairs S. Rajaratnam said that “[t]o pretend that [Raffles] did not found Singapore would be the first sign of a dishonest society”. He added that the statue had narrowly escaped demolition by the early PAP. “We started off as an anti-colonial party. We have passed that stage – only Raffles remains.”21

That same year, Donald and Joanna Moore’s popular history book The First 150 Years of Singapore was published, marking a century-and-a-half since British arrival on the island. In the book, Prime Minister Lee is described as a latter-day Raffles. “The first one hundred and fifty years of Singapore open and close under the aegis of a great man: Raffles, a beacon of almost blinding light at the beginning, pointing the way; Lee Kuan Yew, successor… Raffles and Lee Kuan Yew have, as we shall see, much in common, not only in themselves, but in their stars.”22

Thus, during the initial decades of Singapore’s independence, Raffles was lionised. Between 1962 and 1966, E.W. Jesudason, Principal of Raffles Institution, wrote a school anthem, “Auspicium Melioris Aevi”, picturing Raffles as a classical hero, holding “the torch/That cast Promethean Flame”.23 In 1972, the Singapore Tourist Promotion Board (now Singapore Tourism Board) erected a second Raffles statue, in white polymarble, at his landing site on the north bank of the Singapore River, near Boat Quay.

Later, companies began co-opting his name, resulting in commercial enterprises such as Raffles City Shopping Centre (1986), Raffles Country Club (1988; now defunct), Singapore Airlines’ Raffles Class (1990; renamed Business Class in 2006), the Raffles Cup horse races (1991), Raffles Town Club (2000) and Raffles Hospital (2002).

Writers, too, paid tribute. They retold Raffles’ story in works such as Hereward Brown and Ian Senior’s musical The Lion of Singapore (1979), Nigel Barley’s travelogue The Duke of Puddle Dock: Travels in the Footsteps of Stamford Raffles (1991),24 Asiapac Books’ children’s graphic novel Stamford Raffles: Founder of Modern Singapore (2002),25 and Victoria Glendinning’s biography Raffles and the Golden Opportunity 1781–1826 (2012).26

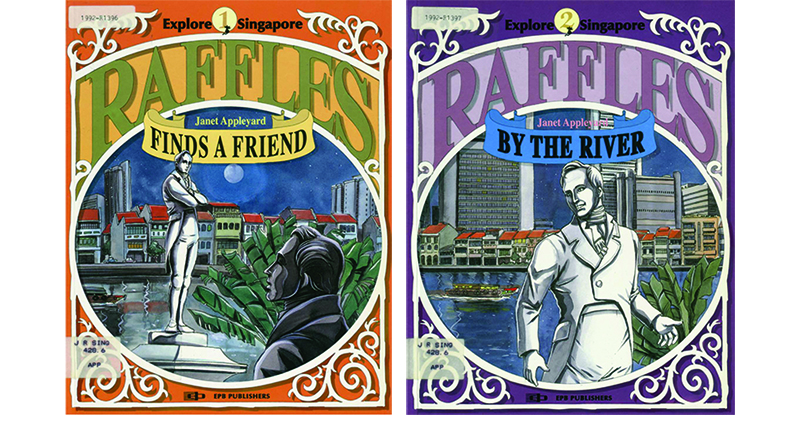

Perhaps the strangest of these texts is Janet Appleyard’s picture book series, Explore Singapore (1992–94). The first volume, Raffles Finds a Friend, is a standard biography of the man. But there is little exploration of history in the five subsequent titles: Raffles by the River, Raffles Meets the Merlions, Raffles and the Elephant, Raffles at Raffles and Raffles Happy Birthday.27 Instead, these books narrate the adventures of the two Raffles statues as they come to life at night and frolic around modern Singapore.

Raffles Finds a Friend is a standard biography of the man, while Raffles by the River narrates the adventures of the two Raffles statues as they come to life at night and frolic around modern Singapore. These two books are part of Janet Appleyard’s six-volume picture book series, Explore Singapore. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Accession nos.: B04216016I; B04216015H).

Raffles Finds a Friend is a standard biography of the man, while Raffles by the River narrates the adventures of the two Raffles statues as they come to life at night and frolic around modern Singapore. These two books are part of Janet Appleyard’s six-volume picture book series, Explore Singapore. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Accession nos.: B04216016I; B04216015H).

The work is, in a sense, the natural result of the endless reduplication of Raffles’ name and image. To many, he is no longer a historical figure but a mere icon, utterly disassociated from colonial violence and subjection, gently tinged with the nostalgic grandeur of a bygone age.

Raffles Reviled (1971 onwards)

There were, of course, counter-narratives to this onslaught of praise. In 1971, sociologist Syed Hussein Alatas published Thomas Stamford Raffles, 1781–1826: Schemer or Reformer? This text considers not only Raffles’ role in recruiting slaves for Alexander Hare’s settlement in Banjarmasin, but also his involvement in the massacre of the Dutch and Javanese in Palembang; his racist writings about Chinese, Malays and Arabs; and his failure to speak out regarding social injustice in the United Kingdom. “Raffles was just one of the hundreds of enthusiastic pioneers of empire building moved by the lust for gain,” Alatas concludes. “[C]ompared to the wider circle of thinkers and reformers, he was philosophically and ethically a dwarf.”28

In 1977, Ronald Alcantra won the Ministry of Culture Playwriting Competition with a script titled An Eclipse Leaves No Shadows.29 This was first performed as a radio play in 1979 and then adapted for TV in 1988. Set in 1823, the play dramatises the power struggle between Raffles and Singapore’s first Resident, William Farquhar. Into the picture enters Syed Yassin,30 a merchant who escapes from prison and runs amok before being killed. Here, Raffles is portrayed as a sickly, tyrannical racist who is stricken by frequent mind-splitting headaches, who snubs Farquhar for marrying a Eurasian wife, and who cruelly parades Syed Yasin’s corpse through the streets as a warning to all who dared to defy British authority.

However, it is in the field of Malay literature that we see a truly sustained critique of Raffles. In 1980, the prolific poet and writer Suratman Markasan published “Balada Seorang Lelaki di Depan Patung Raffles” (“The Ballad of a Man Before the Statue of Raffles”) in the journal Sasterawan. The five-part poem imagines a madman in contemporary Singapore, screaming curses at Raffles’ statue, blaming him for the impoverishment of the Malay race:

“… serentak lelaki hilang kepala bingkas

‘Dosamu tujuh turunan kusumpah terus

kau membawa Farquhar dan Lord Minto

siasatmu halus. Membuka pintu kotaku

pedagang buru pemimpin menambah kantung

membangun Temasek menjadi Singapura

masuk sama penipu perompak pembunuh

aku sekarang tinggal tulang dan gigi cuma

kusumpah tujuh turunanmu tanpa tangguh!’…”

(Translation)

“Suddenly, the man who has lost his mind springs to his feet

‘Your sins for seven generations I put a curse on

you brought with you Farquhar and Lord Minto

your intelligence was subtle. By opening my city doors

traders, labourers, leaders filled up their pockets

they developed Temasek into Singapore

swindlers, robbers, murders all entered too

I’m now left with only bones and teeth

I curse you seven generations now!’…”31

In later Malay works that touch on Raffles, the tendency is to focus more on the Malays who interacted with him. In Mohamed Latiff Mohamed’s 2007 poem “Raffles”, he is portrayed as exploitative, viewing Singapore as “a utopia/to be owned/to be possessed”, but the poet’s real scorn is reserved for the Malays who embrace him: They are “fools nary of dignity”.32

In Isa Kamari’s novel Duka Tuan Bertakhta33 (His Majesty’s Sorrow) (2011), published in English as 1819,34 Raffles is depicted as a conniving, manipulative man intent on stripping the Sultan and Temenggong of their power and participating in sinister Freemasonic rites. However, the heart of the story is about the Malay men who were left defenceless without a credible leader to protect them from the British.

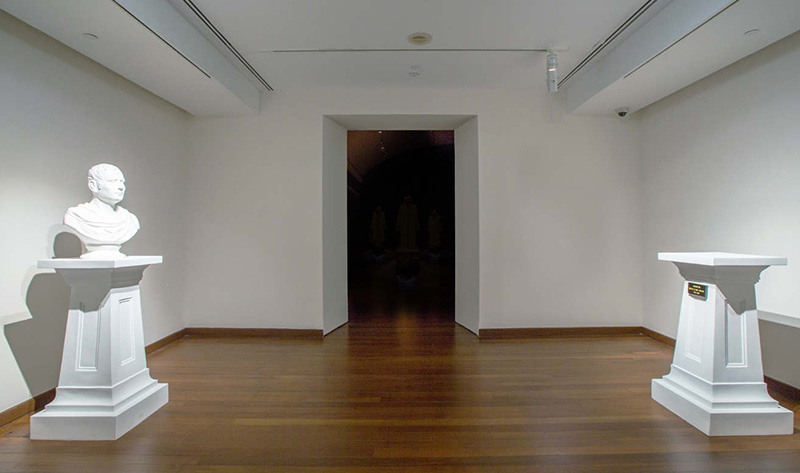

Fyerool Darma’s installation, The Most Mild-Mannered Men, created for the fifth edition of the Singapore Biennale in 2016, captures the Malay perspective on Raffles. The work consists of two chalk-white pedestals: one bears a grotesquely bloated bust of Raffles, while the other stands empty, bearing only a plaque inscribed with the name of the Sultan who signed the treaty with him in 1819: “Hussein Mu’azzam Shah, 1776–1835”. Expressing fury towards the colonist is not the only part of an anti-colonial struggle; artists also seek to remember those who were colonised – not just the winners of history, but also the losers.

Fyerool Darma’s installation, The Most Mild-Mannered Men, for the fifth edition of the Singapore Biennale, 2016. The work consists of two chalk-white pedestals: one bears a grotesquely bloated bust of Raffles, while the other stands empty, bearing only a plaque inscribed with the name of the Sultan who negotiated with him: “Hussein Mu’azzam Shah, 1776–1835”. Courtesy of Fyerool Darma.

Fyerool Darma’s installation, The Most Mild-Mannered Men, for the fifth edition of the Singapore Biennale, 2016. The work consists of two chalk-white pedestals: one bears a grotesquely bloated bust of Raffles, while the other stands empty, bearing only a plaque inscribed with the name of the Sultan who negotiated with him: “Hussein Mu’azzam Shah, 1776–1835”. Courtesy of Fyerool Darma.

Riff-Raff (1989 onwards)

In the early 1980s, the professor and poet Robert Yeo was struck by a whimsical idea: what if Raffles and Lee Kuan Yew were to meet face to face? This was the inspiration for his play The Eye of History, first presented in excerpted form at the National University of Singapore’s Voices of Singapore reading in 1989, followed by a full staging in 1992.

To the contemporary eye, the script appears rather lacking in conflict. When Raffles makes his appearance at the Istana on his 200th birthday, Lee is surprised, but unflustered. They drink wine and make cordial conversation. Raffles compliments Lee as “a leader who takes a long and enlightened view of history”,35 while Lee agrees to consider Raffles’ recommendations to preserve more of Raffles’ heritage – for instance, by making his birthday (5 July) a public holiday.

What is revolutionary, however, is the fact that Raffles and Lee are portrayed as ordinary humans, not untouchable leaders. Raffles is written as someone who likes the musical Cats, shops at local department store Metro and wears batik shirts. This is iconoclasm of another sort: the status of the colonist is diminished to that of an ordinary citizen.

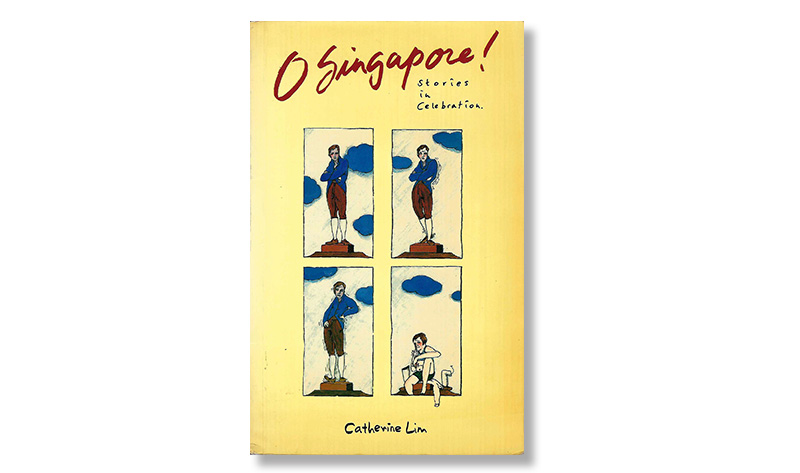

We see similar gestures elsewhere: illustrator Shirley Eu imagines Raffles stripping down to his singlet and picking his nose on the cover of Catherine Lim’s O Singapore!: Stories in Celebration (1989);36 cartoonist Prudencio Miel has him speaking Singlish on the cover of An Essential Guide to Singlish (2003);37 and the Singapore Tourism Board’s advertising campaign Let the Stars Guide You (2017) shows him chowing down at food courts and buying clothes in Orchard Road.

The cover illustration for Catherine Lim’s O Singapore!: Stories in Celebration by illustrator Shirley Eu shows Raffles stripping down to his singlet and picking his nose, 1989. Image reproduced from Lim, C. (1989). O Singapore!: Stories in Celebration. Singapore: Times Books International. (Call no.: R S828 LIM).

The cover illustration for Catherine Lim’s O Singapore!: Stories in Celebration by illustrator Shirley Eu shows Raffles stripping down to his singlet and picking his nose, 1989. Image reproduced from Lim, C. (1989). O Singapore!: Stories in Celebration. Singapore: Times Books International. (Call no.: R S828 LIM).

The cover illustration for An Essential Guide to Singlish drawn by Prudencio Miel shows Stamford Raffles speaking in Singlish, 2003. Image reproduced from Ma, M.P., & Hanna, S. (2003). An Essential Guide to Singlish. Singapore: Gartbooks. (Call no.: RSING 427.95957 ESS).

The cover illustration for An Essential Guide to Singlish drawn by Prudencio Miel shows Stamford Raffles speaking in Singlish, 2003. Image reproduced from Ma, M.P., & Hanna, S. (2003). An Essential Guide to Singlish. Singapore: Gartbooks. (Call no.: RSING 427.95957 ESS).

An especially memorable example is Colin Goh and Woo Yen Yen’s Talking Cock: The Movie (2002). In the comedy, he is portrayed as an object of utter ridicule. In one scene, Raffles bestows Singapore its name after a Malay woman screams “Singh kapuk!” (“The Sikh man has stolen something!”) and fantasises about a future mental institution full of young boys in tight shorts, which he will call Raffles Institution.

A behind-the-scenes photo from Colin Goh and Woo Yen Yen’s Talking Cock: The Movie, 2002. In the comedy, Stamford Raffles is portrayed as an object of utter ridicule. Courtesy of Colin Goh.

A behind-the-scenes photo from Colin Goh and Woo Yen Yen’s Talking Cock: The Movie, 2002. In the comedy, Stamford Raffles is portrayed as an object of utter ridicule. Courtesy of Colin Goh.

There are, of course, works that attempt to seriously and sympathetically engage with Raffles. But increasingly, these stories have a more nuanced take, underscoring the fact that that he died in the prime of his life, in debt and dishonour, bereft of almost all his children.

We see this in Charles Mandel’s horror thriller Days of Sir Raffles (1998),38 which imagines him unleashing and then suffering under an ancient curse. I conveyed the same message in my play The Last Temptation of Stamford Raffles (2008), which reconstructs the last 12 hours of Raffles’ life. In Kent Chan’s 2014 video work To the Eastward (The Lines Divide) and Brian Gothong Tan’s 2016 multimedia performance Tropical Traumas: A Series of Cinematic Choreographies, we not only hear of Raffles’ misfortunes, but see how he, and all other historical actors, are eclipsed by the majesty of the indigenous rainforest.

Ng Yi-Sheng’s play, The Last Temptation of Stamford Raffles, reconstructs the last 12 hours of Raffles’ life. It was staged by W!ld Rice in 2008. Courtesy of W!ld Rice.

Ng Yi-Sheng’s play, The Last Temptation of Stamford Raffles, reconstructs the last 12 hours of Raffles’ life. It was staged by W!ld Rice in 2008. Courtesy of W!ld Rice.

Meanwhile, some artists have chosen to elevate the “common man” to stand as Raffles’ equal. Lee Wen’s installation Untitled (Raffles) (2000) consisted of a scaffold that visitors could climb to look the polymarble Raffles statue in the eye. Vertical Submarine’s Foreign Talent (2007) featured a statue of a foreign construction worker placed directly opposite Raffles’ statue.

Foreign Talent by Vertical Submarine, 2007, featured a statue of a foreign construction worker placed directly opposite the statue of Stamford Raffles. Courtesy of Vertical Submarine (Justin Loke and Joshua Yang).

Foreign Talent by Vertical Submarine, 2007, featured a statue of a foreign construction worker placed directly opposite the statue of Stamford Raffles. Courtesy of Vertical Submarine (Justin Loke and Joshua Yang).

More often, however, there has been an interest in memorialising other historical figures. Haresh Sharma’s play Singapore (2011) entirely omits Raffles from the narrative of early Singapore, focusing instead on William Farquhar and his Eurasian wife Nonio Clement. Rosie Milne’s novel Olivia and Sophia (2015)39 transfers the focus to his wives, describing the process of colonisation through their eyes.

These various approaches were echoed with the opening event of the Singapore Bicentennial. On 31 December 2018, the polymarble Raffles statue along the Singapore River was painted over to give the optical illusion that it had been removed. On 5 January 2019, four additional statues were temporarily installed next to the Raffles statue: that of Sang Nila Utama, Munsyi Abdullah, Tan Tock Seng and Naraina Pillai.

These two works – Teng Kai Wei’s Raffles’ “Disappearance” and Hong Hai Environmental Art’s The Arrivals – signal the new relationship Singaporeans have with Raffles in the 21st century: he has been displaced from the centre of our attention. He is no longer the leading man in the pageant of history, but simply another member of the huge and varied cast.

Raffles-lessness? (Forthcoming)

All this raises the question: should the statue of Raffles be removed? Suggestions to remove it have provoked angry responses from those who want the monument to remain intact.40 Evidently, a significant proportion of Singaporeans still view Raffles as worthy of reverence.

Nonetheless, Raffles has, in a sense, already fallen. More and more contemporary writers and artists have vilified, minimised or sidelined his legacy. Works of history such as Studying Singapore Before 180041 (2018) and Seven Hundred Years: A History of Singapore42 (2019) have extended the timeline of Singapore’s past, demoting Raffles to a mere a bit player in the grander scheme of the Singapore story.

On 27 June 2020, an online discussion, Still “Essential”?: Roundtable on the Icon of Stamford Raffles, was organised by The Substation. The panellists emphasised that symbolic gestures such as removing statues are nowhere as important as acts of reparation. Museums and other cultural institutions would do well to shift their attention away from British colonists, and focus instead on reactivating the heritage of disenfranchised indigenous communities such as the Orang Laut (“sea people”).

Panellist Faris Joraimi noted that much of the commentary assumed that those who wanted to tear down the statues were vandals who wanted to remove historical markers in a violent manner. However, it does not necessarily have to be that way, he said:

“We don’t have to pull him down to the sound of drumbeats and toss him into the river. It could be a solemn ceremony. Would we be reading Suratman Markasan’s poem? Would we be reading Hussein Alatas? It could actually be a sober moment for us to take stock of our symbolic departure from colonial narratives and our beholdenness to colonial past as a source of legitimacy. It could be a powerful moment of national reflection that marks the beginning of a renewed self-confidence.”

| This article has its foundation in the author’s earlier essay, “Raffles Restitution: Artistic Responses to Singapore’s 1819 Colonisation”, first published in the Journal of Southeast Asian Studies (Volume 50, Issue 4, December 2019, pp. 599–631). |

Ng Yi-Sheng is a poet, fictionist, playwright and researcher. His books include his debut poetry collection last boy, which won the Singapore Literature Prize in 2008; the short story collection Lion City, which won the Singapore Literature Prize in 2020, and the performance lecture compilation Black Waters, Pink Sands.

Ng Yi-Sheng is a poet, fictionist, playwright and researcher. His books include his debut poetry collection last boy, which won the Singapore Literature Prize in 2008; the short story collection Lion City, which won the Singapore Literature Prize in 2020, and the performance lecture compilation Black Waters, Pink Sands.

NOTES

-

Stamford Raffles. (2020, June 8). I’d like to declare that I can’t swim. #StatueLivesMatter [Tweet]. Retrieved from Twitter. ↩

-

Sholihyn, I. (2020, June 11). Amid global backlash against colonialists, netizens ask what about Raffles? AsiaOne. Retrieved from AsiaOne website. ↩

-

Vasagar, J. (2020, June 17). Singapore should tear down its statue of Raffles. Nikkei Asia. Retrieved from Nikkei Asia website. ↩

-

Hannigan, T. (2012). Raffles and the British invasion of Java. Singapore: Monsoon Books Pte Ltd. (Call no.: RSEA 959.82 HAN) ↩

-

Alexander Hare (1775–1834) was an English merchant infamous for his polygamous lifestyle. Raffles, as Lieutenant-Governor of Java, appointed Hare Resident of Banjarmasin and Commissioner of the Island of Borneo. ↩

-

Wright, N.H. (2017). William Farquhar and Singapore: Stepping out from Raffles’ shadow. Penang, Malaysia: Entrepot Publishing. (Call no.: RSING 959.5703 WRI-[HIS]) ↩

-

This theatre project has led to the publication of a new non-fiction work, Raffles Renounced: Towards a Merdeka History, edited by Alfian Sa’at, Faris Joraimi and Sai Siew Min, and published by Ethos Books (2021). ↩

-

Raffles, T.S. (1817). The history of Java (Vols. 1 and 2). London: Printed for Black, Parbury, and Allen, booksellers to the Hon. East-India Company, Leadenhall Street, and John Murray, Albemarle Street. (Call no.: RRARE 959.82 RAF-[JSB]; Accession nos.: B29029409B [v. 1]; B29029410E [v. 2]) ↩

-

Raffles, S. (1830). Memoir of the life and public services of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles: Particularly in the government of Java 1811–1816, and of Bencoolen and its dependencies, 1817–1824: With details of the commerce and resource of the Eastern Archipelago, and selections from his correspondence. London: J. Murray. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

Barnard, T. (2019). Commemorating Raffles: The creation of an imperial icon in colonial Singapore. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 50 (4), pp. 579–598. Retrieved from ResearchGate. ↩

-

Munshi Abdullah (1849). Hikayat Abdullah. Singapore: B.P. Keasberry. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

Some scholars have argued that Munsyi Abdullah was in fact subtly critiquing Raffles in his writings. See Sweeney, A. (2006). Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir Munsyi: A man of bananas and thorns. Indonesia and the Malay World, 34 (100), pp. 223–245. Retrieved from ResearchGate. ↩

-

The Jubilee. (1887, July 6). Straits Times Weekly Issue, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Jubilee Prize. (1887, June 2, 10, 29). The Rafflesian, 63–64. Available via PublicationSG. [Note: the winner of the competition, Lim Koon Tye, also wrote an epitaph, although it was ultimately not used.] ↩

-

Centenary of Singapore. Celebrations brilliantly successful. (1919, February 7). The Straits Times, p. 27. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Empire Marketing Board was formed in May 1926 to promote intra-Empire trade without the use of tariffs and to persuade consumers to “Buy Empire”. ↩

-

James Cook was an explorer, navigator, cartographer and captain in the British Royal Navy. In 1770, he charted New Zealand and the Great Barrier Reef of Australia. ↩

-

Cecil John Rhodes was Prime Minister of Cape Colony (now South Africa) from 1890 to 1896. Rhodes and his British South Africa Company founded the southern African territory of Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe and Zambia), which the company named after him in 1895. ↩

-

The Pageant of Empire was the name given to various historical pageants celebrating the British Empire, which were held in the early 20th century. The most elaborate pageant was the one in London – from April to October 1924 – featuring a cast of 15,000 people, 300 horses, 500 donkeys, 730 camels, 72 monkeys, 1,000 doves, seven elephants, three bears and one macaw. It apparently took three days to watch the entire performance. ↩

-

Lee, K.Y. (1996, December 10). Singapore is indebted to Winsemius: SM. The Straits Times, p. 32. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Raffles. (1969, August 7). The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Donald, M., & Donald, J. (1969). The first 150 years of Singapore (p. 1). Singapore: Donald Moore Press in association with the Singapore International Chamber of Commerce. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 MOR) ↩

-

The institution anthem. Retrieved from RAMpage. ↩

-

Barley, N. (1991). The Duke of Puddle Dock: Travels in the footsteps of Stamford Raffles. London: Viking. (Call no.: RSING 325.31092 BAR) ↩

-

Zhou, Y., & Goh, G. (2002). Stamford Raffles: Founder of modern Singapore. Singapore: Asiapac Books. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.57092 ZHO-[JSB]) ↩

-

Glendinning, V. (2012). Raffles and the golden opportunity 1781–1826. London: Profile Books. (Call no.: RSING 959.57021092 GLE-[HIS]) ↩

-

Appleyard, J. (1992). Raffles finds a friend. Singapore: EPB Publishers. (Call no.: RSING 428.6 APP); Appleyard, J. (1992). Raffles by the river. Singapore: EPB Publishers. (Call no.: RSING 428.6 APP); Appleyard, J. (1994). Raffles meets the Merlions. Singapore: EPB Publishers. (Call no.: RSING 428.6 APP); Appleyard, J. (1994). Raffles and the elephant. Singapore: EPB Publishers. (Call no.: RSING 428.6 APP); Appleyard, J. (1994). Raffles at Raffles. Singapore: EPB Publishers. (Call no.: RSING 428.6 APP); Appleyard, J. (1994). Raffles happy birthday. Singapore: EPB Publishers. (Call no.: JRSING 428.6 APP) ↩

-

Syed Hussein Alatas. (2020). Thomas Stamford Raffles: Schemer or reformer? (p 101). Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.5703092 ALA-[HIS]) [Note: The title is also available as an ebook on NLB OverDrive.] ↩

-

Yeo, R. (Ed.). (1980). Prize-winning plays. Singapore: Federal Publications for Ministry of Culture. (Call no.: RSING S822 PRI) ↩

-

Syed Yassin was an Arab merchant who owed Syed Omar Aljunied, another Arab merchant, a large sum of money. Syed Omar then sued Syed Yassin for the debt. William Farquhar ruled in Syed Omar’s favour and ordered Syed Yassin to repay the debt or face imprisonment. On 11 March 1823, Syed Yassin escaped from his prison cell, killed a police peon and severely wounded Farquhar, before he was killed by Farquhar’s son. Raffles then paraded Syed Yassin’s corpse around town and later displayed it in a cage hung from a mast. Syed Yassin was only buried a fortnight later. See Davies, D. (1954, August 15). The day the holy man ran amok. The Straits Times, p. 14. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Suratman Markasan. (2014). Suratman Markasan puisi-puisi pilihan = Selected poems of Suratman Markasan (p. 23). Singapore: National Library Board. (Call no.: Malay RSING 899.281 KAR) ↩

-

Mohamed Latiff Mohamed. (2017). A crackle of flames, a circle of rainbow: Selected poems (p. 146). Singapore: Ethos Books. (Call no.: RSING 899.281 MOH) ↩

-

Isa Kamari. (2011). Duka Tuan Bertakhta. Kuala Lumpur: Al-Ameen Serve Holdings. (Call no.: Malay RSING 899.283 ISA) ↩

-

Isa Kamari. (2013). 1819. (R Krishnan, Trans.). Kuala Lumpur: Silverfish Books Sdn Bhd. (Call no.: RSING 899.283 ISA) ↩

-

Yeo, R. (2016). The eye of history (p. 37). Singapore: Epigram Books. (Call no.: RSING S822 YEO) ↩

-

Lim, C. (1989). O Singapore!: Stories in celebration. Singapore: Times Books International. (Call no.: R S828 LIM) ↩

-

Ma, M.P., & Hanna, S. (2003). An essential guide to Singlish. Singapore: Gartbooks. (Call no.: RSING 427.95957 ESS) ↩

-

Mandel, C. (1998). Days of Sir Raffles. Singapore: Federal Publications. (Call no.: RSING 823 MAN) ↩

-

Milne, R. (2015). Olivia and Sophia. Singapore: Monsoon Books. (Call no.: RSING 823.92 MIL) ↩

-

Aldgra, F. (2020, June 23). IPS research assistant receives abusive comments after former NMP Calvin Cheng beseech his FB followers to “tell him off”. The Online Citizen. Retrieved from The Online Citizen website. ↩

-

Kwa, C.G., & Borschberg, P. (Eds). (2018). Studying Singapore before 1800. Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 STU-[HIS]) ↩

-

Kwa, C.G., Heng, D., Borschberg, P., & Tan, T.Y. (2019). Seven hundred years: A history of Singapore (p. 19). Singapore: National Library Board and Marshall Cavendish International. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 KWA-[HIS]) ↩