Many generations of Singaporeans have shopped in Robinsons since its founding in 1858. Gracie Lee and Kevin Khoo highlight some milestones in its illustrious history.

The Robinsons building in Raffles Place, 1950s. The store’s name is also displayed in Chinese and Malay on the signboard. The statue of Mercury is perched on the top of the arch.

Chiang Ker Chiu Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

After surviving 162 years, the Great Depression, being bombed by the Japanese during World War II, several economic downturns and a devastating fire in 1972, the curtains have finally come down on home-grown department store Robinsons – once hailed as “one of the handsomest shops in the Far East”.¹

In August 2020, Robinsons closed its store in Jem shopping mall. Barely four months later, its flagship luxury store in The Heeren followed suit. Its last outlet at Raffles City Shopping Centre shuttered in January 2021.

High-quality merchandise and impeccable service set Robinsons apart when it opened in 1858, and the store quickly became popular with the European community and Malay royalty. Even King Mongkut of Siam was a loyal customer and was known to have signed off his letters to Robinsons as “your good friend”. Famous people who graced its portals back in its heyday included Britain’s Prince Philip, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and singer Cliff Richard.²

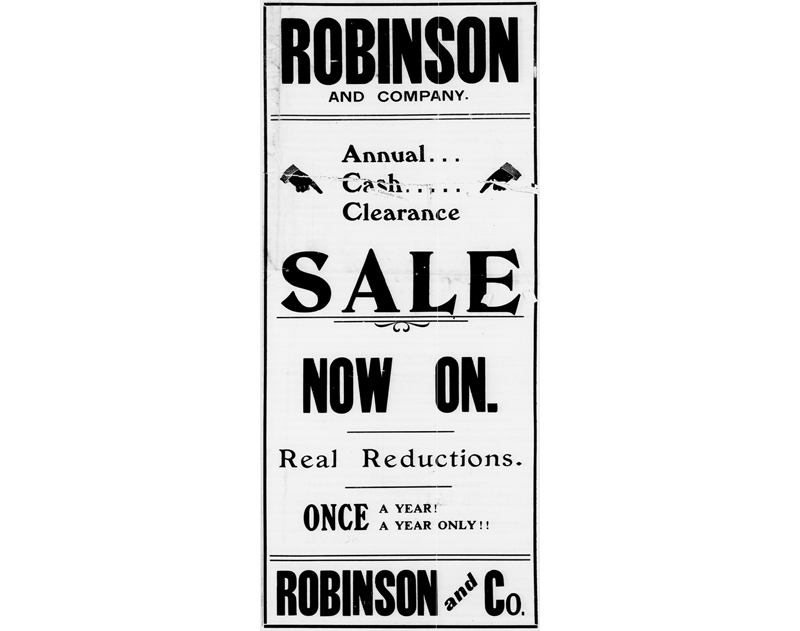

Over the years, Robinsons served countless Singaporeans, many of whom became friendly with staff who had worked in the store for decades. The annual Robinsons’ sale, touted as “the sale truly worth waiting for”, was one of the highlights of Singapore’s shopping calendar.

What felled the retail giant? Declining sales due to changing consumer tastes and the rising popularity of online shopping were contributing factors. The reduced footfall to its outlets was exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic that ravaged the world for much of 2020.

As Singaporeans bid farewell to a much-loved icon, we look back at some of the defining moments in Robinsons’ storied past gleaned from newspaper reports in NewspaperSG, annual reports and inhouse newsletters kept by the National Library, and oral history interviews and images from the National Archives.

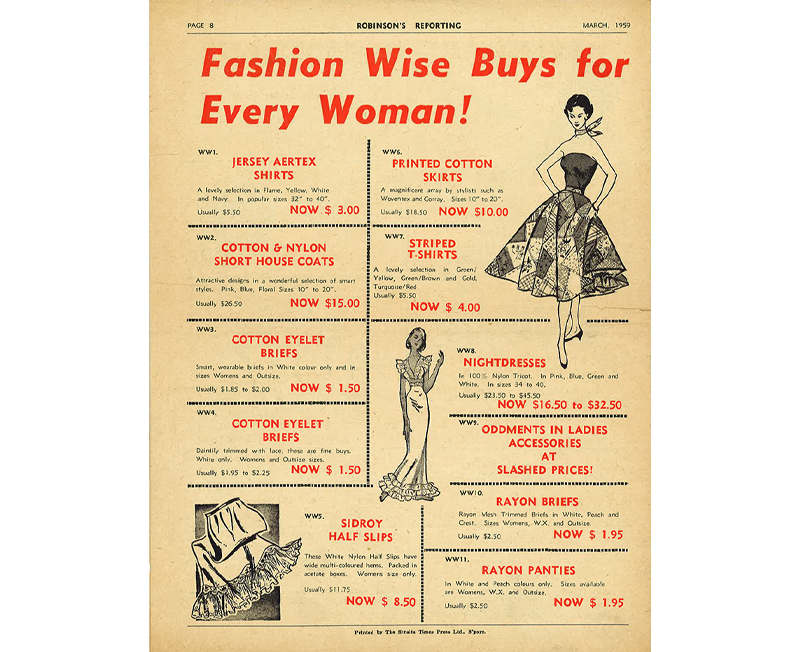

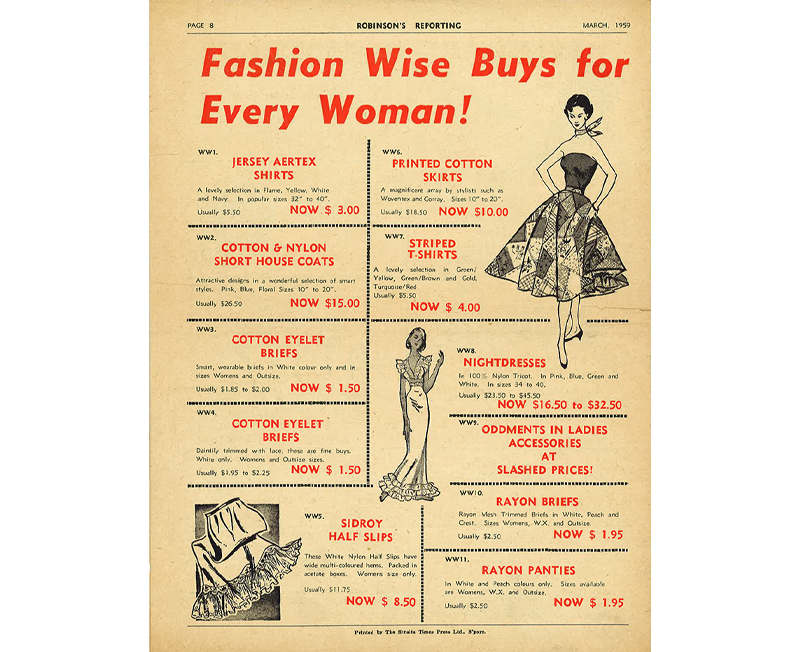

The Robinsons “Big Sale” in 1959 took place from 23 March to 11 April, with substantial discounts storewide. Shoppers could write in to order their items and collect them later. Image reproduced from Robinson & Co. Ltd. (1959, March 2). This is Robinson’s reporting from Singapore. Singapore: Robinson & Co. Ltd. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Accession no.: B28906607E).

The Robinsons “Big Sale” in 1959 took place from 23 March to 11 April, with substantial discounts storewide. Shoppers could write in to order their items and collect them later. Image reproduced from Robinson & Co. Ltd. (1959, March 2). This is Robinson’s reporting from Singapore. Singapore: Robinson & Co. Ltd. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Accession no.: B28906607E).

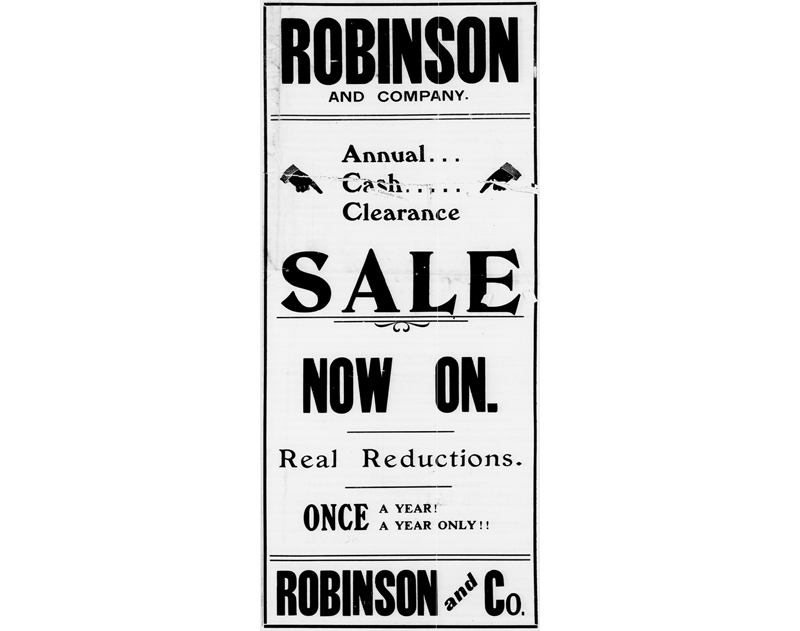

Robinsons advertising its annual sale in 1907. The Straits Times, 5 September 1907, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Robinsons advertising its annual sale in 1907. The Straits Times, 5 September 1907, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

NOTES

| HOW ROBINSONS GOT ITS NAME |

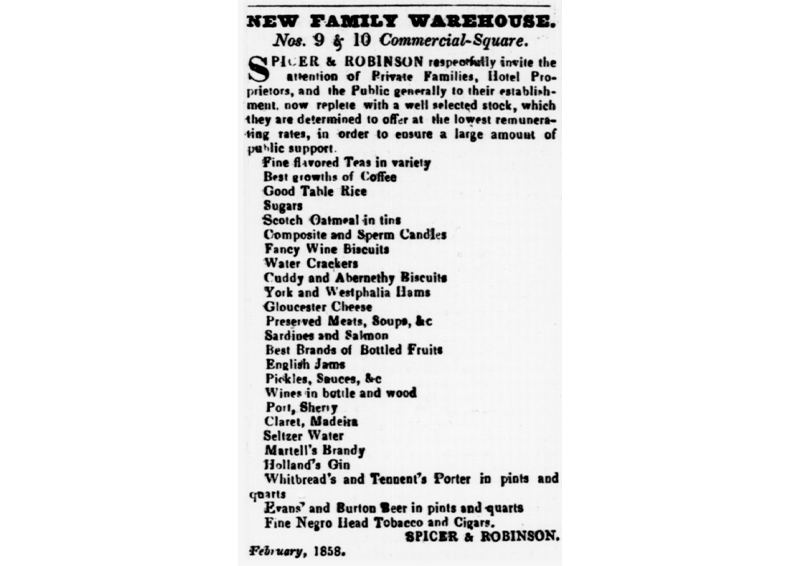

| The grand dame’s history can be traced back to 1 February 1858 when Philip Robinson, who came from Australia, and James Gaborian Spicer, a former keeper at the Singapore Jail, opened Spicer & Robinson at Nos. 9 & 10 Commercial Square (now Raffles Place). |

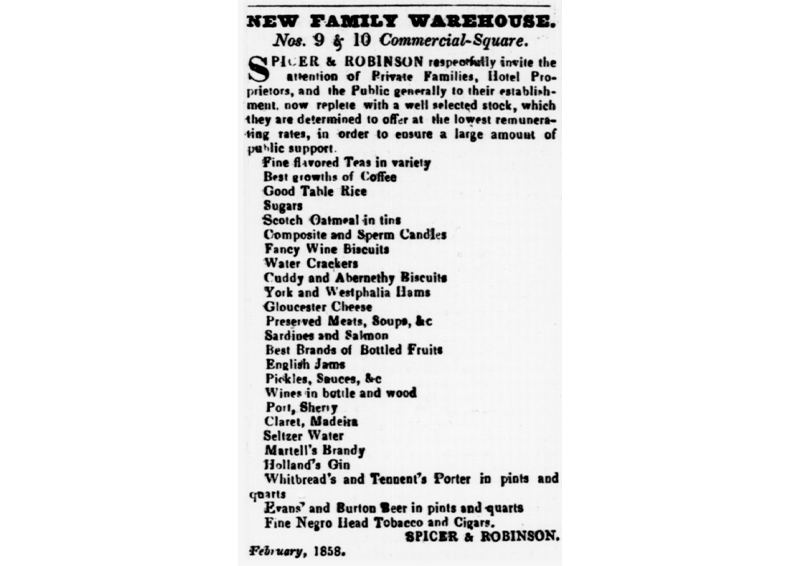

| An 1858 advertisement for the “New Family Warehouse”, as it was called, went: “Spicer & Robinson respectfully invite the attention of Private Families, Hotel Proprietors, and the Public generally to their establishment, now replete with a well selected stock, which they are determined to offer at the lowest remunerative rates, in order to ensure a large amount of public support.”¹ The store sold items such as tea, rice, sugar, oatmeal, biscuits, crackers, cheese, preserved meats and women’s hats. |

| A year later, the store was renamed Robinson and Company when Robinson’s partnership with Spicer was dissolved and George Rappa, Jr. came on board. After Robinson’s death in 1886, his son, with the splendid name of Stamford Raffles Robinson, succeeded him. One A.W. Bean was also brought in as a partner. The business flourished and was incorporated as a limited company in 1920. The firm then came under the management of a hired general manager and a board of directors comprising members such as prominent businessman Eu Tong Sen.² |

Spicer & Robinson’s first newspaper advertisement. The company started out as a family warehouse in Commercial Square (now Raffles Place). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 25 February 1858, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. Spicer & Robinson’s first newspaper advertisement. The company started out as a family warehouse in Commercial Square (now Raffles Place). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 25 February 1858, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. |

| 1. New Family Warehouse. (1858, February 25). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. |

| FROM HIGH-END TO HIGH STREET |

| Robinsons began life as a high-end store when it opened, setting out to woo customers with its wide array of quality merchandise, excellent service and eye-catching displays. By the turn of the 20th century, the store had become a household name among British “mems”, European expatriates and the well-heeled of Singapore society. |

| Robinsons made a name for itself as a one-stop shopping paradise, with departments dedicated to drapery, haberdashery, millinery, home furnishings, bicycles, photographic apparatus, sporting equipment, musical instruments, and even arms and ammunitions used for game hunting. |

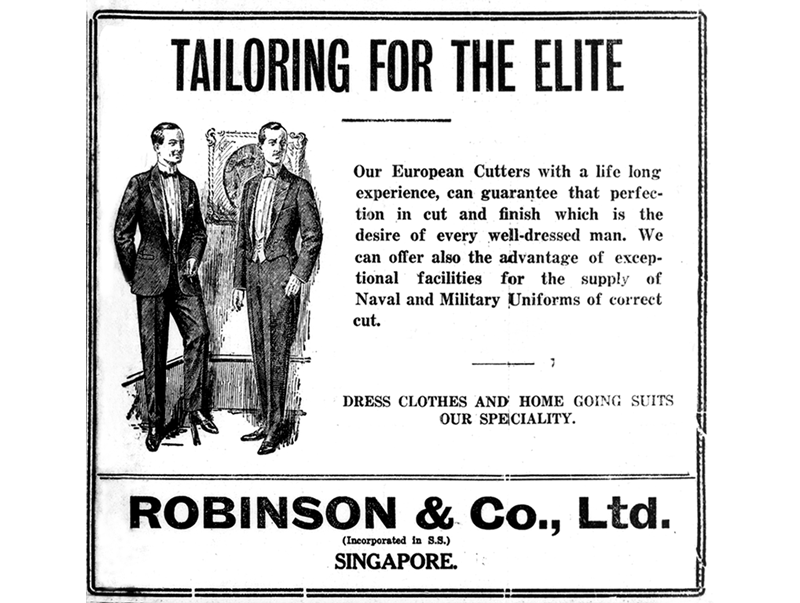

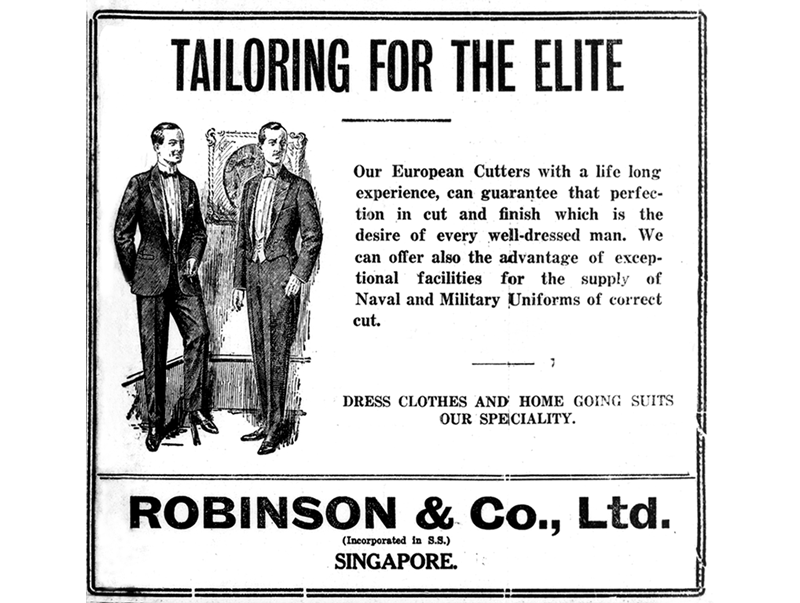

| It was said that wealthy Straits Chinese women would travel from Kuching in Sarawak to Singapore just to buy Swiss voile, which could only be found in Robinsons. To appeal to female shoppers, the store later offered dressmaking services that included bespoke clothing sent all the way from London. |

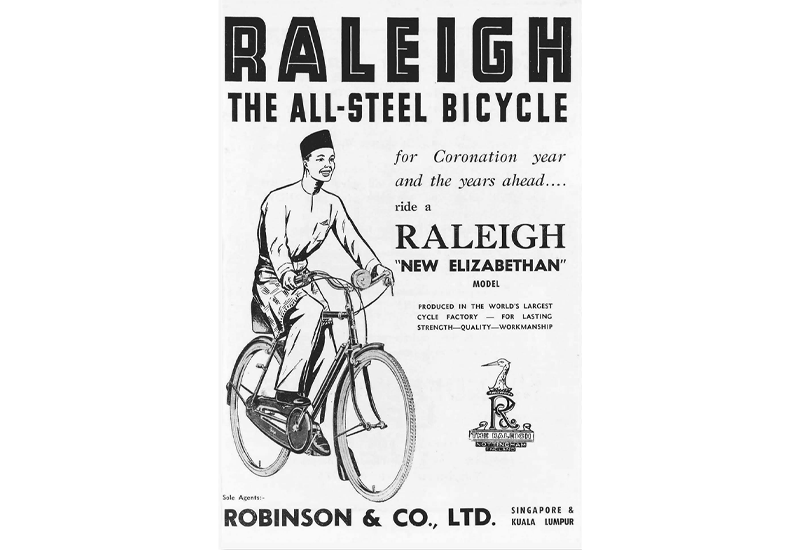

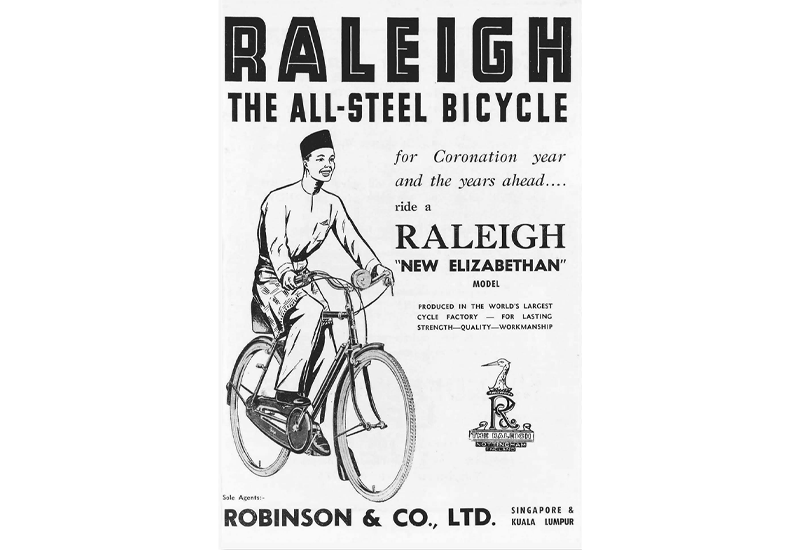

| Robinsons was also a trailblazer in introducing new shopping experiences and brands exclusive to the store, such as Hennessy brandy and Heineken beer. In 1907, Robinsons became among the world’s first agents for Raleigh bicycles and, by the 1950s, had sold more than half a million of such bicycles. |

| Unfortunately, Robinsons’ reputation as a high-end shopping destination put off some people. Polytechnic lecturer Ng Joo Kee, who was born in 1959 and lived in nearby Chulia Street, recalled that Robinsons was particular about who could enter its premises. It was “a very up-market kind of a department store and we were very poor. We usually [wore] singlets, and shorts and slippers and we weren’t allowed in”. It was only when the underground carpark in Raffles Place opened in 1965, giving people access to the supermarket at Robinsons, that he managed to sneak into the store.¹ |

| By the 1970s and 80s, as Singapore’s economy took off and disposable incomes rose, Robinsons began carrying a wider range of products to cater to the emerging middle class. Over time, Robinsons grew in popularity among shoppers from all walks of life. |

| In 2013, its new owners decided to revive the store’s luxury roots: its premises at The Centrepoint were closed and a new, decidedly more upscale, flagship store opened at The Heeren. However, the attempt to target more affluent customers failed. According to retail experts, Robinsons ended up being too expensive for the general public, but at the same time, it was not attractive enough for the well-heeled.² |

Robinsons advertising the services of its experienced European cutters who offered bespoke clothing for “every well-dressed man”. The Straits Times, 17 November 1928, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. Robinsons advertising the services of its experienced European cutters who offered bespoke clothing for “every well-dressed man”. The Straits Times, 17 November 1928, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. |

In 1907, Robinsons became among the world’s first agents for Raleigh bicycles, a British brand. For the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II, Raleigh launched its “New Elizabethan” model of bicycles, which were sold in Robinsons. Image reproduced from The Straits Times Annual, 1954, p. 131. In 1907, Robinsons became among the world’s first agents for Raleigh bicycles, a British brand. For the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II, Raleigh launched its “New Elizabethan” model of bicycles, which were sold in Robinsons. Image reproduced from The Straits Times Annual, 1954, p. 131. |

| 1. Yap, W.C. (Interviewer). (1997, November 3). Oral history interview with Ng Joo Kee [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 001970/4/1, p. 4]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. |

| 2. Low, Y. (2020, November 2). Upmarket or mass market? Retail experts say Robinsons’ confused identity contributed to its closure. Today. Retrieved from Today website. |

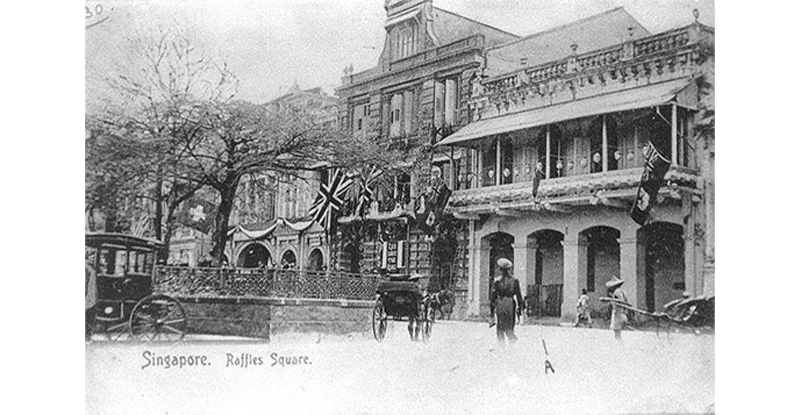

| In Singapore, Robinsons relocated several times in the course of its long history. The store’s first move took place in 1859 when it shifted from its original site in Commercial Square to the corner of Coleman Street and North Bridge Road. The new site was a stone’s throw away from the Esplanade (Padang), the heart of social life in 19th-century Singapore. |

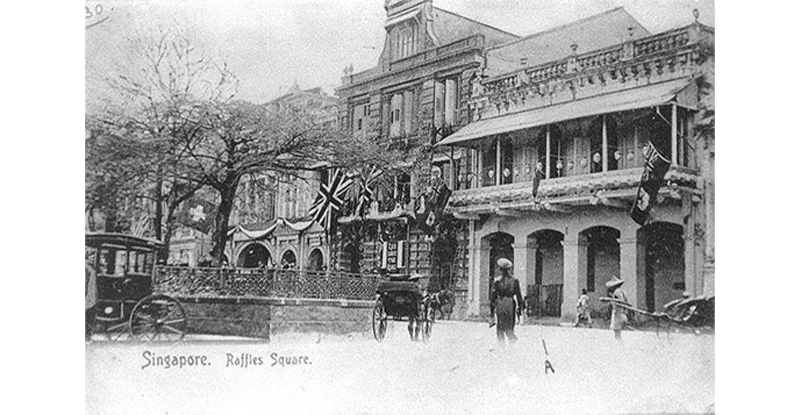

| In 1881, Robinsons opened a new shop with a tailoring department on Battery Road. Ten years later, it returned to Commercial Square – by then renamed Raffles Place – and occupied much larger premises. In November 1941, the store moved to Raffles Chambers, located on the opposite side of Raffles Place. |

Raffles Place c. 1901. Robinsons occupied the two buildings on the extreme right, before moving to Raffles Chambers in 1941. Andrew Tan Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore. Raffles Place c. 1901. Robinsons occupied the two buildings on the extreme right, before moving to Raffles Chambers in 1941. Andrew Tan Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore. |

| This new store was met with approval by the press. Noted a news report: “Those who have visited it already have remarked on its spaciousness, the modern way of displaying the merchandise so that you can walk all round it, the wide entrance where you can wait for your car in comfort.” The ground floor housed the “men’s clothing and tailoring departments, leather goods, confectionary, cosmetics, perfumes, gramophones and sports goods, silverware. On the first floor you have women’s departments, dresses for children, furnishing and dress materials, household linens, haberdashery, shoes and the like”. The second floor featured an air-conditioned cafe as well as hair salons for men and women.¹ |

| Business came to a halt during the Japanese Occupation (1942–45), and resumed only in April 1946. Operating from the same iconic location at Raffles Place, Robinsons became the first department store in Southeast Asia to be fully air-conditioned in 1955. After a facelift in 1957, the name “Robinsons” on its facade was also displayed in Malay and Chinese, envisioning its future in a self-governing Singapore.² |

Raffles Place in 1965. The Overseas Union Bank building is on the extreme left and Robinsons department store just next to it. In the middle is the Chartered Bank building with the dome, while the tall building on the right is Bank of China. Arshak C. Galstaun Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore. Raffles Place in 1965. The Overseas Union Bank building is on the extreme left and Robinsons department store just next to it. In the middle is the Chartered Bank building with the dome, while the tall building on the right is Bank of China. Arshak C. Galstaun Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore. |

| Tragedy struck in 1972 when a huge fire razed the store to the ground. The store reopened in less than a month at Specialists’ Shopping Centre on Orchard Road – Singapore’s prime shopping district.³ To keep its links with the original site in Raffles Place, Robinsons opened a branch at Clifford Centre in 1977 but this closed in 1983.⁴ That same year, the store decamped across the road to Centrepoint Shopping Centre (now known as The Centrepoint). |

| The Centrepoint store was where the management pinned its hopes on regaining the lustre lost after the disastrous fire. In the company’s in-house newsletter in 1983, Chief Executive Loh Man Chee wrote that “your management has [sic] determined to regain the lost leadership of Robinson’s being ‘the shopping place’ for families in South East Asia”. He noted that the company had invested more than $10 million in fixing up the new store. “Great effort has been made to give the new store a new look and to reinforce our merchandising objectives – superior quality and value.”⁵ |

| The store was a major tenant in Centrepoint until 2013 when it moved to The Heeren.⁶ |

| Robinsons also opened other outlets in Singapore. A branch in Raffles City was unveiled in 2001 to reach out to younger customers. In 2013, Robinsons expanded into the suburbs with an outlet in Jem, a shopping mall in Jurong East.⁷ |

| Robinsons also expanded overseas, launching its first overseas outlet in 1928 in Kuala Lumpur, though this closed in 1975. The company re-entered the Malaysian market with stores at The Gardens Mall in 2007 and The Shoppes at Four Seasons Place in 2018 (both ceased operations in December 2020⁸). |

| Although all of Robinsons’ stores in Singapore and Malaysia have closed, the time-honoured trade name lives on through its sole store at the Dubai Festival City Mall in the United Arab Emirates, a development opened in 2017 by the Al-Futtaim Group, which acquired Robinsons in 2008.⁹ |

| 1. Heathcott, M. (1941, September 30). In The “New Family Warehouse”. The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. |

| 3. Robinson & Co. (Singapore). (1973). Annual report 1973 (p. 3). Singapore: The Company. (Call no.: RCLOS q338.47658871 RCSAR) |

| 4. Pereira, A. (1983, November–December). History of Clifford Centre Branch. Robinson’s Group Berita [n.p.]. (Accession no. B28739090E) |

| 5. A step forward in difficult time. (1983, July-August). Robinson’s Group Berita [n.p.]. (Accession no. B28739088A) |

| 6. Robinson & Co. (Singapore). (1983). Annual report 1983 (p. 9). (Call no.: RCLOS q338.47658871 RCSAR-[AR]); Zachariah, N.A. (2013, November 9). Robinson’s fancy new home. The Straits Times, p. 16. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. |

| 8. Robinson’s & Co, 1958, [n.p.]; David, A. (2020, December 21). End of an era as Robinsons closes in Malaysia. New Straits Times. Retrieved from New Straits Times website. |

| 9. Fung, E. (2008, April 4). Sold – Robinson’s now owned by Dubai’s Al-Futtaim. Today, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Dubai Festival City Mall. (2021). Robinsons. Retrieved from Dubai Festival City Mall website. [Note: Robinsons’ main shareholder OCBC Bank sold its stake to Indonesia’s Lippo Group in 2006. Robinsons was acquired by the Al-Futtaim Group in 2008.] |

| ROBINSONS DURING WORLD WAR II |

| In July 1941, Robinsons held its annual shareholder meeting in Singapore. This took place amidst the backdrop of World War II which had broken out in Europe in 1939.¹ When the company’s Chairman W.H. MacGregor addressed shareholders on 28 July, Britain was still reeling from aerial bombings by the Luftwaffe, the German air force, which had taken place between September 1940 and May 1941. |

| Fortunately, as the war had not yet reached the shores of Britain’s colonies in Southeast Asia, Robinsons managed to turn a profit. In 1941, the company reported profits amounting to more than $270,000, almost double its pre-war 1939 earnings. Robinsons shareholders received dividends ranging from 5 percent to 8 percent, depending on the class of stock each person owned. Even after the payouts, there were substantial funds left over to fill the company’s coffers. Despite the ongoing war in Europe, the store had plenty of fine goods on display as the company was able to procure supplies from Australia.² |

| At the shareholder meeting in 1941, MacGregor ruefully noted that “there may be some who will suggest that the increased profit is due to advantage having been taken of war conditions… [t]o a limited extent that perhaps is true, but it is a truism which applies to every business… and is difficult to avoid… [the] policy of the Board, however, has been to maintain prices at a reasonable level, and I should like to emphasise that the improved results this year have resulted from greatly increased turnover rather than from large profit margins”. MacGregor also announced that the company had earlier contributed $5,000 towards the War Fund and would be making a further donation of $5,000.³ |

| At the same time, MacGregor sounded a note of caution. “Conditions at the present time make it difficult to foresee what the future may bring.” He assured shareholders that “however much the spending power of the public is contracted, or import bans extended, there will always be goods to sell and there will also be buyers of these goods, and we can rest assured that we shall have a full share of any business passing”.⁴ |

| Just five month later, on 8 December 1941, the Imperial Japanese Army dropped the first bombs on Singapore. Some of these landed on Robinsons, which damaged its beautiful frontage. Although Robinsons declared the store “Open as usual” the following day, rubble piled up at the entrance of its premises. In the last days before the fall of Singapore, the cafe in Robinsons became a rallying point for the European community, packed with civilians and servicemen as many deserted the business district and eateries bolted their doors.⁵ The store was struck again by bombs on 13 February 1942 and was later looted. |

| Robinsons was closed throughout the three-and-a-half years of the Japanese Occupation (1942–45). It only reopened for business in April 1946 and in the first year of operations, managed to reap a profit of over a million dollars. |

| MacGregor did not live to see Robinson’s post-war restoration as he had died in March 1942 during his internment by the Japanese.⁶ |

Robinsons’ frontage was damaged after Japanese bombs fell on the building on 8 December 1941. The next day, the store advertised that it was “Open as usual”. Image reproduced from Robinsons & Co. (Singapore). (2018). Robinsons 160 Extraordinary Years: 1858–2018 (p. 4). Singapore: Robinsons. (Accession no.: B29960618H). Robinsons’ frontage was damaged after Japanese bombs fell on the building on 8 December 1941. The next day, the store advertised that it was “Open as usual”. Image reproduced from Robinsons & Co. (Singapore). (2018). Robinsons 160 Extraordinary Years: 1858–2018 (p. 4). Singapore: Robinsons. (Accession no.: B29960618H). |

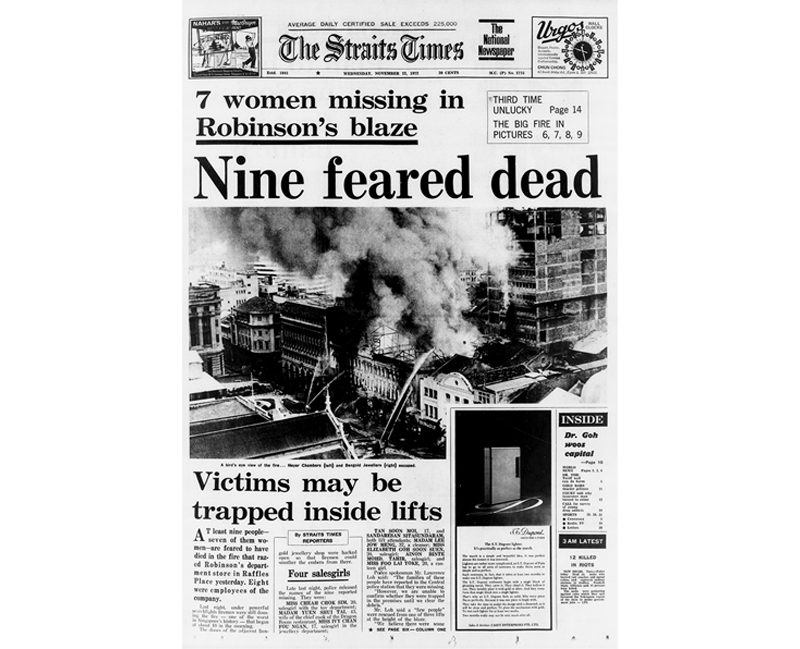

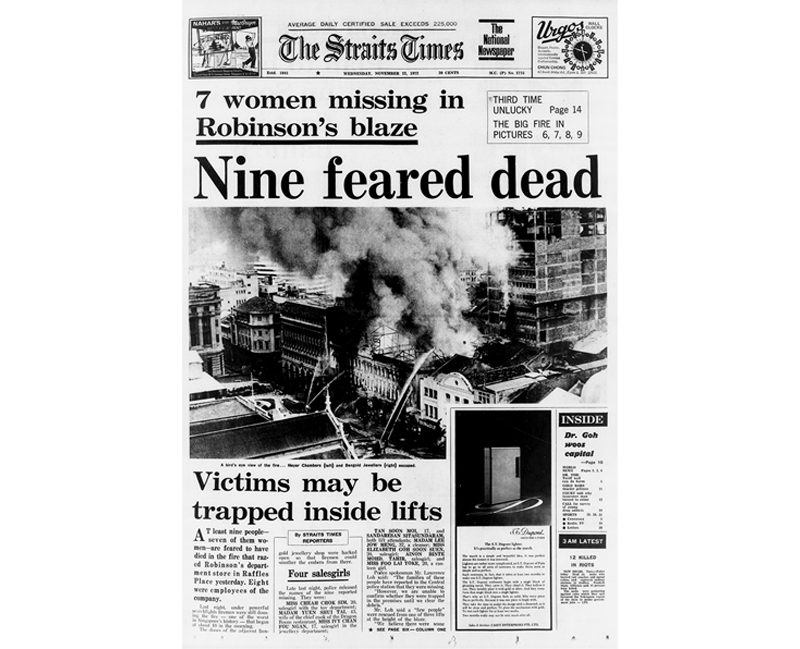

| On Tuesday, 21 November 1972, an overloaded electrical system short-circuited on the ground floor of the buiding and started a fire at about 9.50 am.¹ According to The Straits Times, “a Robinson’s salesman in the Men’s Department said he saw a flash across some electrical wire running along the ground floor ceiling near the jewellery counter. The drapes on the wall were set ablaze, he said, and within minutes the fire had spread across the room”. The flames that engulfed the building soared as high as 200 ft (61 m) at one point, with the conflagration reportedly visible as far away as Toa Payoh and Jurong.² |

| Nine people died in the fire, eight of whom were trapped in the store’s lifts. Out of the nine fatalities, eight were employees. The fire gutted the entire building, leaving only a shell, and incinerated millions of dollars worth of goods stockpiled for Christmas. It also damaged neighbouring buildings, including the roof of the adjoining Overseas Union Bank. Businesses across Raffles Place and the commercial district were forced to stop for the day, and thousands of workers were evacuated from their offices.³ |

The Straits Times put the news of the Robinsons fire on the front page. The Straits Times, 22 November 1972, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. The Straits Times put the news of the Robinsons fire on the front page. The Straits Times, 22 November 1972, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. |

| George Yuille Cadwell was a medical doctor whose practice was located at the Bank of China building across from the store. “I was busy working and didn’t notice anything and… [one of my patients] came in [and said] ‘Robinsons is on fire!’,” he recalled. “And I looked out of the window and I saw lots of smoke coming out of the building and flames coming out of the windows… a very, very big fire. And I noticed that as the flames got higher and higher, this little tiny figure of winged Mercury [on the roof of the Robinsons building] just slowly melting in the heat and folding over and dropping down. And I could feel the heat through the glass of my window [although] we must have been 200 yards away? It was quite warm… The buildings [at Raffles Place] are all joined together… as Robinsons was built just of wooden floors and wooden rafters. And so it went up [in flames] very quickly, very dry.”⁴ |

| Tan Wee Him, a journalist with The Straits Times who covered the fire, was another eyewitness. “I received a call from my office… ‘We need every available journalist to cover the fire that broke out at Robinson.’… When I [reached] Robinsons, I couldn’t believe [it]. The whole place was a towering inferno. The flame was shooting up and even this bronze statue right at the top of the roof of Robinsons melted. You can just imagine the heat generated… I had to hide behind pillars… to protect myself from the heat.”⁵ |

| The fire brigade arrived at 10.13 am and attempted to put out the blaze but the nearby fire hydrants were not functioning as they should as the water pressure was too low. Although efforts were made to divert and supply water from other mains, the water pressure fell again at noon and the firemen resorted to pumping water directly from the Singapore River. By late afternoon, a fleet of 18 fire engines had been deployed to the scene. The police later cordoned off most of Raffles Place for public safety and to prevent looting. The total value of the Robinsons building, the goods destroyed and loss of profits was estimated to be about $14 million.⁶ |

The Robinsons store in Raffles Place engulfed in flames. The fire on 21 November 1972 completely gutted the building and destroyed millions of dollars worth of goods. Nine people died in the fire. Image reproduced from Robinsons and Company (Singapore). (2002, December). Family News: The Staff Newsletter of the Robinsons Group (p. 11). Singapore: The Robinsons Group. (Call no.: RSING 338.47658871 FN). The Robinsons store in Raffles Place engulfed in flames. The fire on 21 November 1972 completely gutted the building and destroyed millions of dollars worth of goods. Nine people died in the fire. Image reproduced from Robinsons and Company (Singapore). (2002, December). Family News: The Staff Newsletter of the Robinsons Group (p. 11). Singapore: The Robinsons Group. (Call no.: RSING 338.47658871 FN). |

| On 21 December 1972, then President Benjamin Sheares officially appointed a Commission of Inquiry to investigate the cause of the fire. The commission found that Robinsons had overloaded its ageing and deteriorating electrical circuitry by installing numerous spotlights and decorative fittings for the festive Christmas period, ignoring warnings of overloading by its own electricians. |

| The commission also noted that Robinsons had inadequate fire safety measures and had, in fact, stored large quantities of combustible goods in unauthorised loft storage areas. In its report released to the public in December 1973, the commission made several recommendations on fire safety and building safety measures to prevent a similar tragedy. Many of the commission’s recommendations were subsequently incorporated into the Building Control Act of 1974, which vested the government with the power to take action against unauthorised building works as well as the owners of dangerous or dilapidated buildings.⁷ |

| Robinsons would bounce back quickly from this disaster. On 11 December 1972, a new Robinsons store opened at Specialists’ Shopping Centre on Orchard Road. The company also made plans to rebuild the store in Raffles Place, but the government had acquired the prime site for urban redevelopment before this could happen.⁸ The site is presently occupied by One Raffles Place, the former OUB Centre. |

| 2. Nine feared dead. (1972, November 22). The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. |

| 5. Chew, H.M. (Interviewer). (2006, June 9). Oral history interview with Tan Wee Him [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 003058/07/03, pp. 65–67]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. |

Gracie Lee

Gracie Lee is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore, and works with its Rare Materials Collection.

Kevin Khoo

Kevin Khoo is a Senior Manager with the Oral History Centre at the National Archives of Singapore.

Back to Issue

The Robinsons building in Raffles Place, 1950s. The store’s name is also displayed in Chinese and Malay on the signboard. The statue of Mercury is perched on the top of the arch. Chiang Ker Chiu Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The Robinsons building in Raffles Place, 1950s. The store’s name is also displayed in Chinese and Malay on the signboard. The statue of Mercury is perched on the top of the arch. Chiang Ker Chiu Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The Robinsons “Big Sale” in 1959 took place from 23 March to 11 April, with substantial discounts storewide. Shoppers could write in to order their items and collect them later. Image reproduced from Robinson & Co. Ltd. (1959, March 2). This is Robinson’s reporting from Singapore. Singapore: Robinson & Co. Ltd. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Accession no.: B28906607E).

The Robinsons “Big Sale” in 1959 took place from 23 March to 11 April, with substantial discounts storewide. Shoppers could write in to order their items and collect them later. Image reproduced from Robinson & Co. Ltd. (1959, March 2). This is Robinson’s reporting from Singapore. Singapore: Robinson & Co. Ltd. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Accession no.: B28906607E). Robinsons advertising its annual sale in 1907. The Straits Times, 5 September 1907, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Robinsons advertising its annual sale in 1907. The Straits Times, 5 September 1907, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Spicer & Robinson’s first newspaper advertisement. The company started out as a family warehouse in Commercial Square (now Raffles Place). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 25 February 1858, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Spicer & Robinson’s first newspaper advertisement. The company started out as a family warehouse in Commercial Square (now Raffles Place). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 25 February 1858, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Robinsons advertising the services of its experienced European cutters who offered bespoke clothing for “every well-dressed man”. The Straits Times, 17 November 1928, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Robinsons advertising the services of its experienced European cutters who offered bespoke clothing for “every well-dressed man”. The Straits Times, 17 November 1928, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. In 1907, Robinsons became among the world’s first agents for Raleigh bicycles, a British brand. For the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II, Raleigh launched its “New Elizabethan” model of bicycles, which were sold in Robinsons. Image reproduced from The Straits Times Annual, 1954, p. 131.

In 1907, Robinsons became among the world’s first agents for Raleigh bicycles, a British brand. For the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II, Raleigh launched its “New Elizabethan” model of bicycles, which were sold in Robinsons. Image reproduced from The Straits Times Annual, 1954, p. 131.

Raffles Place c. 1901. Robinsons occupied the two buildings on the extreme right, before moving to Raffles Chambers in 1941. Andrew Tan Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Raffles Place c. 1901. Robinsons occupied the two buildings on the extreme right, before moving to Raffles Chambers in 1941. Andrew Tan Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore. Raffles Place in 1965. The Overseas Union Bank building is on the extreme left and Robinsons department store just next to it. In the middle is the Chartered Bank building with the dome, while the tall building on the right is Bank of China. Arshak C. Galstaun Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Raffles Place in 1965. The Overseas Union Bank building is on the extreme left and Robinsons department store just next to it. In the middle is the Chartered Bank building with the dome, while the tall building on the right is Bank of China. Arshak C. Galstaun Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Robinsons’ frontage was damaged after Japanese bombs fell on the building on 8 December 1941. The next day, the store advertised that it was “Open as usual”. Image reproduced from Robinsons & Co. (Singapore). (2018). Robinsons 160 Extraordinary Years: 1858–2018 (p. 4). Singapore: Robinsons. (Accession no.: B29960618H).

Robinsons’ frontage was damaged after Japanese bombs fell on the building on 8 December 1941. The next day, the store advertised that it was “Open as usual”. Image reproduced from Robinsons & Co. (Singapore). (2018). Robinsons 160 Extraordinary Years: 1858–2018 (p. 4). Singapore: Robinsons. (Accession no.: B29960618H).

The Straits Times put the news of the Robinsons fire on the front page. The Straits Times, 22 November 1972, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

The Straits Times put the news of the Robinsons fire on the front page. The Straits Times, 22 November 1972, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. The Robinsons store in Raffles Place engulfed in flames. The fire on 21 November 1972 completely gutted the building and destroyed millions of dollars worth of goods. Nine people died in the fire. Image reproduced from Robinsons and Company (Singapore). (2002, December). Family News: The Staff Newsletter of the Robinsons Group (p. 11). Singapore: The Robinsons Group. (Call no.: RSING 338.47658871 FN).

The Robinsons store in Raffles Place engulfed in flames. The fire on 21 November 1972 completely gutted the building and destroyed millions of dollars worth of goods. Nine people died in the fire. Image reproduced from Robinsons and Company (Singapore). (2002, December). Family News: The Staff Newsletter of the Robinsons Group (p. 11). Singapore: The Robinsons Group. (Call no.: RSING 338.47658871 FN). Gracie Lee is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore, and works with its Rare Materials Collection.

Gracie Lee is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore, and works with its Rare Materials Collection.

Kevin Khoo is a Senior Manager with the Oral History Centre at the National Archives of Singapore.

Kevin Khoo is a Senior Manager with the Oral History Centre at the National Archives of Singapore.