A Rugged Society: Adventure and Nation-Building

The call to create a “rugged society” in Singapore has resonated through the decades. Shaun Seah looks at how the policy shaped young people in the 1960s.

Youths crossing a rope structure over a river during an obstacle course at the Outward Bound School on Pulau Ubin, 1967. The school was opened in 1967 to forge ruggedness and solidarity among students through experiences outside the classroom. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Youths crossing a rope structure over a river during an obstacle course at the Outward Bound School on Pulau Ubin, 1967. The school was opened in 1967 to forge ruggedness and solidarity among students through experiences outside the classroom. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

In the immediate post-independence years, Singapore faced a number of challenges: it was a small city-state with few natural resources, its access to the larger market of Malaysia was circumscribed because of political wrangling, and it had a limited ability to defend itself.

Singapore’s future would lie in the hands of its young people and the political leadership of the time felt that this group needed to be better prepared for the challenges ahead. At a Queenstown Community Centre National Day celebration held on 10 August 1966, then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew noted:

“It is the young that will determine what happens to this society… It depends on the education we give them; the training they receive; the values that they are taught… whether you should have a soft society, fun-loving, pleasure-loving, weak, effete or whether you should have a rugged, robust, disciplined, effective society, a hard society, a tough, rugged society…”1

Recalling his years in Raffles Institution, Lee decried his privileged colonial education as having reared a “whole generation of softies… weak from want of enough exercise, enough sunshine, and with not enough guts in them”. He believed that the education system overemphasised examinations and paper qualifications. His government instead sought to produce “a whole generation… prepared to stand up and fight and die” for Singapore.2

Lee felt that a “soft” society would not be up to the task of taking on the manifold challenges that newly independent Singapore would face. What was needed instead was a “tough, rugged society”.

The need for a generation prepared to “fight and die” was literal, not just metaphorical. In March 1967, Parliament passed the landmark National Service (Amendment) Bill, which made it mandatory for all able male Singaporeans to serve in the Singapore Armed Forces (SAF) for two years.

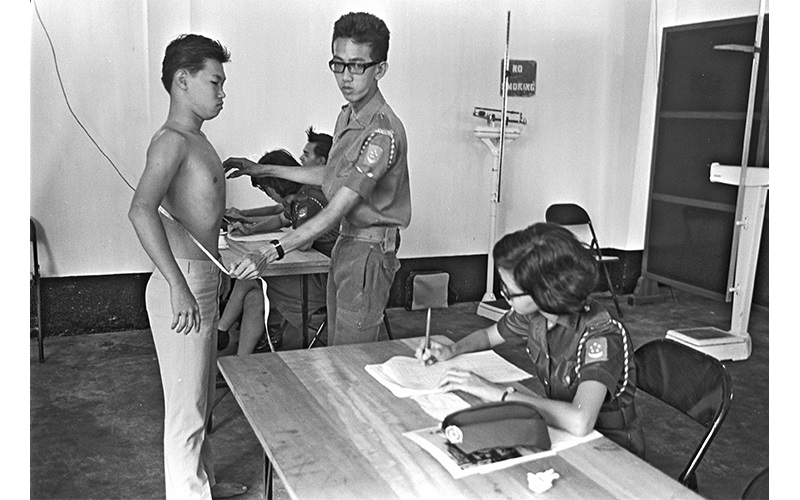

The National Service (Amendment) Bill passed in Parliament on 14 March 1967 made National Service compulsory for all 18-year-old male Singapore citizens and permanent residents. The registration exercise for the first batch of recruits was held from 28 March to 18 April that year. In this photo taken on the first day of registration, a recruit is given a health check to ensure that he is medically fit for rigorous military training. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The National Service (Amendment) Bill passed in Parliament on 14 March 1967 made National Service compulsory for all 18-year-old male Singapore citizens and permanent residents. The registration exercise for the first batch of recruits was held from 28 March to 18 April that year. In this photo taken on the first day of registration, a recruit is given a health check to ensure that he is medically fit for rigorous military training. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

With universal conscription, it was also necessary to ensure that those called up to do their National Service would be relatively prepared. A generation of recruits who were “weak from want of enough exercise,” would not do well in uniform. It was certainly unlikely that such youths would be prepared to “stand up and fight and die” for Singapore.

The Rugged Society in School

One way of creating this rugged society would be to have outdoor activities emphasised in schools through what were then called extra-curricular activities (ECAs) such as uniformed groups like the scouts and the National Cadet Corps (NCC). ECAs were cited by one Straits Times journalist as “the word that put new life in schools in Singapore”.3

To stress the importance of ECAs among students and their (presumably exam-conscious) parents, from 1967 onwards, ECA participation became integrated into national assessment metrics with the award of marks or grades. These would be taken into account for admission to pre-university classes, and applications for bursaries and Public Service Commission scholarships.4

The rugged society did not stop at ECAs though. In 1967, a predecessor of today’s National Physical Fitness Award (NAPFA) was introduced, requiring all students aged 10 and above to undergo a five-station physical test twice a year.5

That same year, Singapore’s branch of the global Outward Bound School (OBS) was opened on Pulau Ubin by then Minister for Defence Goh Keng Swee, specifically to build a rugged society. These initiatives all sought to forge ruggedness and solidarity among students through formative experiences beyond the classroom.

Youths clambering over the A-frame during an obstacle course at the Outward Bound School on Pulau Ubin, 1967. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Youths clambering over the A-frame during an obstacle course at the Outward Bound School on Pulau Ubin, 1967. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A Rugged Society Ready to Defend Itself

The urgency of a building a “rugged society” would only mount with time. On 17 July 1967, Britain announced the imminent withdrawal of British troops from Singapore by 1971. This would be a major economic blow to Singapore as the British military presence generated 20 percent of Singapore’s Gross National Product. It was also estimated that around 25,000 base workers would lose their jobs by 1970.6 The rapid withdrawal of British forces threatened to bring Singapore into a recession.

The same day the withdrawal was announced, then Prime Minister Lee addressed the first batch of Officer Cadets commissioned from the SAF Training Institute (SAFTI) at the Istana. In his speech, Lee identified the qualities of “discipline, grit and stamina” in its citizen army as crucial to Singapore’s national survival. Against the backdrop of mass conscription, Lee exhorted the freshly commissioned officers to train incoming young Singaporean men well so that “what we lack in numbers we will make up for in quality”.7

Drilling from Young

Lee was of the view that a rugged society would be reflected in a credible defence force – and this effort would need to begin in the schools, well before youths enlisted for military service.

Since a rugged society ultimately served the purpose of national defence, much of its rhetoric and initiatives were militaristic in tone. Drill and parades were very much part of the movement. In July 1967, four months after the National Service (Amendment) Bill was passed, the inaugural Singapore Youth Festival (SYF) was held. The festival saw 4,390 students participating in ceremonial military drills, athletic displays and cultural performances over two weeks. By 1970, this figure had risen to 9,000.8 At SYF 1968, Lee refused an umbrella and joined cadets and school children who were getting soaked in a tropical downpour.9

Then Prime Minster Lee Kuan Yew inspecting the guard of honour at the 1968 Singapore Youth Festival held at Jalan Besar Stadium. Lee later refused an umbrella offered to him during a heavy downpour midway through the march-past. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Then Prime Minster Lee Kuan Yew inspecting the guard of honour at the 1968 Singapore Youth Festival held at Jalan Besar Stadium. Lee later refused an umbrella offered to him during a heavy downpour midway through the march-past. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

However, there was no guarantee that marching under the sun (and rain) could attract the enthusiasm and participation of Singapore’s youths. Indeed, as some recalled, all the “drill, left right left, the marching and everything else” simply seemed quite pointless.10

Despite the foot drills, uniformed groups became popular in schools. One reason for the enthusiasm may have been the opportunities these groups accorded young Singaporeans who had less-than-ideal living conditions at home. In 1970, over 38.5 percent of families lived in squatter colonies with limited access to sanitation, water and healthcare, while 13.3 percent resided in often overcrowded shophouses.11 A total of 25 percent of Singaporeans lived in poverty.12

Former scout Jackie Yap used to live in Bukit Ho Swee, “a very notorious area” rife with gangsters, and studied in Bukit Ho Swee Secondary School in the late 1960s. Despite participating in his school’s National Police Cadet Corps (NPCC) activities on Saturday mornings, Yap’s appetite for adventure beckoned and he also joined the local Sea Scout group on Sunday afternoons.

Scouting gave Yap the opportunity to leave behind claustrophobic afternoons at home – crammed into a one-room flat shared with nine other family members. With the scouts, Yap was able to venture outdoors and indulge in his “passion for the sea”, once even rowing around Singapore in a wooden sampan. Yap said that many of his fellow underprivileged peers enjoyed their time with the Sea Scouts because “they could [finally] enjoy space and some form of novel recreation for free”.13

Sea Scouts undergoing training, 1956. Scouting was officially inaugurated in Singapore in 1910, with sea scouting introduced in 1938. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Sea Scouts undergoing training, 1956. Scouting was officially inaugurated in Singapore in 1910, with sea scouting introduced in 1938. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Taylor Eng lived in an overcrowded shophouse along Havelock Road and attended Raffles Institution in the late 1960s. He enjoyed scouting as it provided him an escape from familiar, urban settings. Memorable escapades for him included an overnight hike followed by camping on Singapore’s Mount Faber, and an expedition to the 2,817-metre-high Gunung Tahan, the highest point in the Malay Peninsula, a trip which he remembered fondly as a simply “crazy” idea.14

On 9 August 1968, The Straits Times wrote about a rafting expedition by eight cadets from Sang Nila Utama Secondary School and New Town Integrated School to West Malaysia that spanned more than 110 km over four days.15

From 1975, the NCC (Sea) began its annual Round Island Canoeing Expedition. The expedition typically saw 80 cadets in 40 double-seater canoes doing a full circumnavigation of the Singapore coast, starting from the west bank of the Causeway. Over four days, cadets completed a journey of some 200 km with only overnight stops at SAFTI Boat Station in the west, and the NCC sea training centres in Pasir Panjang and Changi.16

The rugged society was not restricted to boys. Young girls, too, were enthusiastic participants. Chung Cheng High School alumnus Rina Sim, an NCC cadet, relished the air of authority her cadet uniform carried during her daily commute to school from Kampong Chai Chee, happily correcting villagers who mistook her for a za bor mata (Hokkien for “policewoman”). Her experience in the NCC sparked a lifelong passion for the military, and against parental objections, she joined the Republic of Singapore Navy in 1978 even before receiving her bookkeeping examination results.17 She served the navy with distinction and was eventually appointed Chief Clerk in the Naval Diving Unit.

The National Cadet Corps (NCC) girls’ contingent marching through the streets during the 1972 National Day Parade at the Padang. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The National Cadet Corps (NCC) girls’ contingent marching through the streets during the 1972 National Day Parade at the Padang. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Dunearn Secondary NCC cadet Shamsia Muslim was proud that she completed a day-long navigation test in the countryside – the “toughest of all training tests in the NCC”. Shamsia resolutely refused offers of help from passing lorries when she got lost in rural Lim Chu Kang and expressed wonderment at the world beyond her neighbourhood to discover plantations and “hospitable rural dwellers”.18

All these activities left a mark on young, impressionable minds. Former 1960s Rafflesian scout Zainul Abidin bin Mohamed Rasheed (later Senior Minister of State in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs) learned “the sense of service to others” and “the true meaning of life-long friends”.19 Another fellow scout, Kwek Siew Jin (who later became Rear-Admiral and Chief of Navy) believed that scouting “was the best thing that happened” to him in his formative years, resulting in character-building and moral growth.20

Jackie Yap of Bukit Ho Swee Secondary School felt that his time in the Sea Scouts and NPCC taught “a lot of very good survival skills, life skills which [are] today, so important”. Yap later went on to join the Singapore Army as a regular in the Commandos, where he completed the SAF Ranger Course before leaving service in the late 1980s. Today, he works with corporate clients as a team-building consultant, helping participants to enjoy the great outdoors and to understand themselves and nature better.21

Whither the Rugged Society?

While the rugged society rhetoric eventually petered out, such was the appeal of the concept that the call would be resurrected every now and then over the ensuing decades. In 1974, a year of high inflation and economic uncertainty, Haji Sha’ari Tadin, then Member of Parliament for Kampong Chai Chee, recalled the “old rallying call” of the rugged society as he called on Singaporeans to “roll up their sleeves and work even harder” after several years of stellar economic growth.22

In 1980, a New Nation editorial bemoaned the pampered lives of younger generations, believing Singaporeans to have come “a long way and perhaps wrong way away from the rugged society” of the 1960s. The editorial lamented that people no longer woke up at 6.30 am for national fitness exercises but were instead “snoring away on their expensive deluxe beauty rest bed” in an air-conditioned room, before travelling in an air-conditioned vehicle to an air-conditioned office and, after work, relaxing in air-conditioned squash courts, bowling alleys and shopping malls.23

In a 1990 speech at the opening of the College for Physical Education, then First Deputy Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong noted a “disconcerting and unhealthy” trend of rising obesity among youths, and called for a renewed emphasis on physical fitness to eliminate obesity. Singapore has succeeded, he said, because “we dare to strive for excellence. We have to be fit and rugged to meet competition to achieve excellence. I therefore throw you this challenge – get Singaporeans to return to the rugged society”.24 Government anxiety over mounting obesity among youths would see the introduction of fitness initiatives like the Trim and Fit programme in 1992 and the All Children Exercise Simultaneously Day in 1993.

In 2015, the term “rugged society” made another brief reappearance. During Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong’s National Day Rally, he noted that the rugged society was one of three factors crucial to Singapore’s success. Prime Minister Lee said that although the term “rugged society” is not used so often anymore, “our people must still be robust and tough and able to take hard knocks, always striving to be better…. If we are soft and flabby, we are going to be eaten up. We have to be rugged, we have to have that steel in us”.25

Public discourse reflects the centrality of this rugged ideal – take for instance the labelling of “millennials” born between 1980 and 2000 as the “strawberry generation”, incapable of enduring hardship or adverse conditions. Since 2017, a Straits Times feature series has sought to counter this stereotype through stories of perseverance among youths in fighting debilitative diseases, mental health struggles and personal failures in life. The “Generation Grit” series suggests a reframing of the concept of ruggedness to qualities beyond just fitness and physical prowess.26

Shaun Seah is doing his Masters in East Asian Studies at Columbia University. He has a BA (History) from Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge University. Educated at Maris Stella High School and ACS (Independent), he was a Cadet Lieutenant in the National Cadet Corps and a Venture Scout.

Shaun Seah is doing his Masters in East Asian Studies at Columbia University. He has a BA (History) from Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge University. Educated at Maris Stella High School and ACS (Independent), he was a Cadet Lieutenant in the National Cadet Corps and a Venture Scout.

NOTES

-

Ministry of Culture. (1966, August 10). Speech by the Prime Minister, Mr Lee Kuan Yew, at Queenstown Community Centre, August, 10, 1966 [Speech]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Ministry of Culture, 10 Aug 1966. ↩

-

Lee, C.K. (1969, June 23). Extra-curricula: The word that put new life in schools in Singapore. The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Ministry of Culture. (1979, November 16). Speech by Dr Tony Tan Keng Yam, Senior Minister of State for Education, at the National Police Cadet Corps 20th anniversary dinner held at the Silver Star Theatre Restaurant on Friday, 16 November 1979 at 7.30pm [Speech]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Horton, P.A. (2002). Shacking the lion: Sport and modern Singapore. International Journal of the History of Sport, 19 (2–2), 243–274, pp. 254–255. Retrieved from Taylor & Francis Online. ↩

-

Murfett, M.H., et al. (2011). Between two oceans: A military history of Singapore from 1275 to 1971 (p. 329). Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions. (Call no.: RSING 355.0095957 BET); Lee begins talks to avert total British pull-out by 1975. (1967, June 27). The Straits Times, p. 18. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Ministry of Culture. (1967, July 18). Speech by the Prime Minister, Mr Lee Kuan Yew, at the commissioning ceremony of officer cadets into the Armed Forces at Istana on Tuesday, July, 18, 1967 [Speech]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

The children’s hour of enchantment. (1968, July 22). The Straits Times, p. 11; Mammoth parade is festival highlight. (1970, July 15). The Straits Times, p. 20. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. [Note: By 1975, the Singapore Youth Festival would be shortened from a two-week affair to a one-day event.] ↩

-

Lee reviews parade in the rain. (1968, July 21). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Personal interview with Wang Lee Hoon, 10 July 2019. ↩

-

Singapore Department of Statistics. (1970). Table 12.3: Percentage Distribution of Population in Private Households in Urban, Suburban and Rural Census Areas by Type of Census House, 1970. In Report on the census of population 1970 Singapore (Vol. I; p. 233). Singapore: Government Printing Office. (Call no.: RSING 312.095957 SIN) ↩

-

Thum, P.J. (2014). The old normal is the new normal. In D. Low & S. Vadaketh (Eds.), Hard choices: Challenging the Singapore consensus (p. 143). Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING 320.95957 LOW) ↩

-

Personal interview with Jackie Yap, 25 September 2019. ↩

-

Personal interview with Taylor Eng, 17 September 2019. ↩

-

16 to attempt raft trip by river to East-Coast. (1968, August 9). The Straits Times, p. 13. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Ministry of Culture. (1976, February 2). NCC (Sea) second round Singapore island canoeing expedition [Press release]. Retrieved from the National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Personal interview with Rina Sim, 8 July 2019. ↩

-

Shamsia Muslim. (1979). An unforgettable experience. In 1969–1979: 10th anniversary souvenir magazine: Dunearn Secondary School (pp. 110–111). Singapore: The School. (Available via PublicationSG) ↩

-

Singapore Scouts Association. (2010). 100 years of adventure, 1910–2010 (p. 58). Singapore: Singapore Scouts Association. (Call no.: RSING 369.43095957 ONE) ↩

-

Singapore Scouts Association, 2010, p. 80. ↩

-

Personal interview with Jackie Yap, 25 September 2019. ↩

-

Old rallying call of a rugged society in these hard times. (1974, May 5). The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Still the rugged society? (1980, May 31). New Nation, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Goh, C.T. (1990, March 10). Speech by Mr Goh Chok Tong, first Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Defence, at the official opening of the College of Physical Education new facilities at 21 Evans Road, on Saturday, 10 March 1990 at 1800hrs [Speech]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Siau, M.E. (2015, August 24). The three factors behind Singapore’s success. Today, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Tan, T. (2017, December 7). Millennials, redefined: Meet Generation Grit. The Straits Times, p. 27. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩