St Andrew’s Cathedral and the Mystery of Madras Chunam

Was Madras chunam used inside St Andrew’s Cathedral? Maybe not, says Yeo Kang Shua, who has carefully examined the layers of plaster on its interior walls.

Completed in 1865 and consecrated as an Anglican cathedral in 1870, St Andrew’s is a national monument that regularly features in guidebooks of Singapore. Almost every description mentions that the interior walls of the building were plastered with Madras chunam, which is partly made of egg white. Courtesy of Preservation of Sites and Monuments, National Heritage Board.

Completed in 1865 and consecrated as an Anglican cathedral in 1870, St Andrew’s is a national monument that regularly features in guidebooks of Singapore. Almost every description mentions that the interior walls of the building were plastered with Madras chunam, which is partly made of egg white. Courtesy of Preservation of Sites and Monuments, National Heritage Board.

Completed in 1865, St Andrew’s Cathedral1 is a national monument that is regularly featured in guidebooks about Singapore. Built in the English Gothic style, descriptions of this handsome building invariably mention that the interior walls of this Anglican church used a unique form of plaster known as Madras chunam. The rather unusual ingredients that make up Madras chunam – among other things, egg white and coarse sugar – are undoubtedly a key reason why it has become lodged in the popular imagination.

The use of Madras chunam is mentioned in the 1899 book, Prisoners Their Own Warders,2 by John Frederick Adolphus (J.F.A.) McNair of the Madras Artillery who had supervised the construction of the church. (It was consecrated as a church in 1862, before it was fully completed, and re-consecrated as a cathedral in 1870.) In his book, McNair wrote:

“In dealing with the interior walls and columns, we used… ‘Madras chunam’, made from shell lime without sand; but with this lime we had whites of eggs and coarse sugar, or ‘jaggery’, beaten together to form a sort of paste, and mixed with water in which the husks of cocoanuts [sic] had been steeped. The walls and columns were plastered with this composition, and, after a certain period for drying, were rubbed with rock crystal or rounded stone until they took a beautiful polish, being occasionally dusted with fine soapstone powder, and so leaving a remarkably smooth and glossy surface….”3

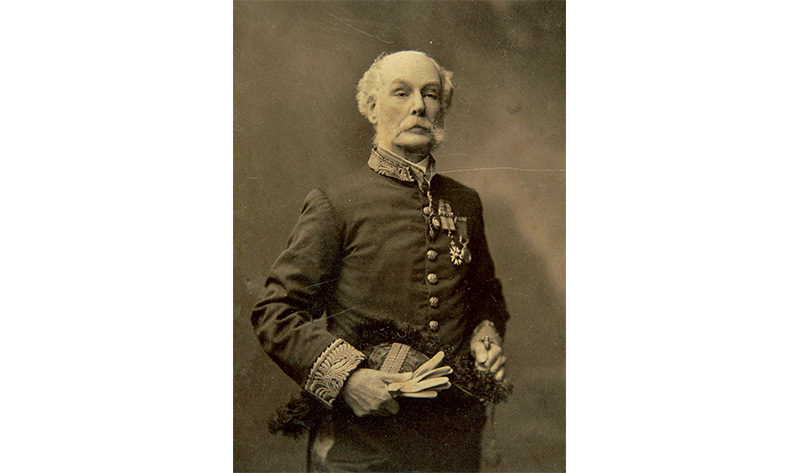

A studio portrait of Major John Frederick Aldophus McNair in his uniform, c. 1900. McNair, who supervised the construction of St Andrew’s Church, recounted in his book, Prisoners Their Own Warders, that Madras chunam was used as a plaster for the interior walls and columns of the church. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

A studio portrait of Major John Frederick Aldophus McNair in his uniform, c. 1900. McNair, who supervised the construction of St Andrew’s Church, recounted in his book, Prisoners Their Own Warders, that Madras chunam was used as a plaster for the interior walls and columns of the church. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

This claim has been repeated many times since, and not merely in guidebooks but also in press reports as well as serious works.4 Indeed, some writers have gone on to suggest that the same plaster was not just found in St Andrew’s, but widely used in Singapore. In a 1981 Straits Times article, author Peter Keys wrote that “Madras (chunam) plasterwork became universally used, with its odd (but since proven to be practical) mixture of shell lime, egg white, sugar and coconut husk…” in Singapore.5

In his 1988 book, Singapore: A Guide to Buildings, Streets, Places, co-written with Norman Edwards, the authors said that some of the buildings in the Serangoon area also featured Madras chunam.6 A 2017 article in The Straits Times even claimed that Madras chunam was used in the Istana (formerly known as Government House),7 despite McNair’s own account that they had used a mixture of Portland cement, sand and powdered granite.8

Over the last 100 years, it has become axiomatic that Madras chunam was used in St Andrew’s. There is, however, just one problem: there is no physical evidence of Madras chunam on the walls of St Andrew’s. For close to a decade, I have been involved in conservation issues pertaining to the interior of St Andrew’s and, as part of this job, I have closely examined and analysed the plaster work at various locations within the building. Despite having taken and analysed numerous samples of the plaster, we have not found any trace of egg white, the tell-tale sign of Madras chunam.

Plaster sampling at one of the columns in St Andrew’s Cathedral. A sample of the plaster was taken from the surface to the brick substrate for laboratory analysis. In this photograph, a thin layer (2–3 mm) of grey Portland cement screed can be seen under the white paint layer. Courtesy of Yeo Kang Shua.

Plaster sampling at one of the columns in St Andrew’s Cathedral. A sample of the plaster was taken from the surface to the brick substrate for laboratory analysis. In this photograph, a thin layer (2–3 mm) of grey Portland cement screed can be seen under the white paint layer. Courtesy of Yeo Kang Shua.

Peeling Back the Mystery

I first became involved with the conservation of the walls of St Andrew’s in 2011. Around that time, the paint on some parts of its interior walls had begun peeling, while in other parts, the plaster had delaminated (the technical term for “popped out”). Because of my background in architectural conservation, I was asked to study and advise the cathedral.

While I began my investigation, the cathedral carried out ad-hoc repairs to the affected areas, mainly behind the lectern as well as around the Epiphany Chapel and pulpit. Two years later, more localised repairs were carried out, this time on the south facade of the west porch, to address the same problem.

In 2016, to prepare for a large-scale and comprehensive plaster repair, the cathedral undertook lime plaster trials at selected interior walls and columns along the south aisle of the building.9 In 2018, further trials using proprietary lime were carried out behind the lectern and pulpit, on the west porch and on the north facade of the west porch.

In addition to these trials, in 2019, the internal walls of the tower (the belfry) were repaired during conservation work on the church bells.

Thus between 2011 and 2019, we had numerous opportunities to sample and study the plaster around many spots within St Andrew’s because of the repair work and the lime plaster trials. However, none of our investigations found any trace of protein (egg white) or fibre (coconut husk). The lime plaster trials in 2016 and 2018, in particular, allowed us to remove the existing plaster ahead of the trial. While doing so, we did find a thin finish coat of Portland cement screed and, in some cases, layers of Portland cement plaster, but no Madras chunam. (The existence of Portland cement attest to subsequent repair and/or replastering at these localised areas.)

Our failure to find Madras chunam on the walls of St Andrew’s was puzzling. Why couldn’t we find any trace of this unique plaster inside the church even though we had done extensive sampling? One possibility is that Madras chunam had been originally used, but was completely stripped away later, which is why no trace can be found today. The more controversial possibility, of course, is that despite McNair’s account, Madras chunam was never actually used inside St Andrew’s.

To unravel this mystery, we must delve into the intricacies of the making and application of Madras chunam, and we need to learn more about how St Andrew’s was built.

Making Madras Chunam

The word chunam is a transliteration of cuṇṇāmpu or choona, which means “lime” in Tamil and Hindi respectively. Madras (now known as Chennai) is a city in Tamil Nadu, India. Madras chunam thus refers to a particular type of lime plaster commonly used in Madras.

One of the earliest descriptions of Madras chunam in English is found in A Practical and Scientific Treatise on Calcareous Mortars and Cements, Artificial and Natural, authored by Louis-Joseph Vicat. His 1837 book describes how shell-lime, sand, sugar, egg white, clarified butter, sour milk and powdered soapstone were used as ingredients to make the coats of this plaster.10

Published in 1840, James Holman’s Travels in Madras, Ceylon, Mauritius, Cormoro Islands, Zanzibar, Calcutta, etc. etc. contains a very detailed description of Madras chunam that bears repeating to get an idea of the work necessary to make the plaster, and how to apply it.

“The lime is of the finest quality, and is produced from sea-shells well washed and properly cleansed, after which they are calcined with charcoal, during which process the greatest care is taken to exclude every thing likely to injure the purity and whiteness of the lime. ….

“The plaster is composed of one part of chunam, or burnt lime, and one and a half of river sand thoroughly mixed, and well beaten up with water. … Before the plaster is applied, the wall must be trimmed… and swept perfectly clean, it should then be slightly sprinkled with water; after the wall is ready the plaster is… mix… with jagghery-water, to a proper consistency, it is then laid on about an inch thick… and levelled…, being afterwards smoothed with a rubber, until it acquires an even surface. During the process of rubbing, the plaster is occasionally sprinkled with a little pure lime mixed with water, to give it a hard and even surface.

“For two coats.

… The plaster used for the second coat consists of three parts of lime, and one of white sand, which is mixed up as before… till it is reduced to a fine paste. The plaster thus prepared is… applied… over the first coat, about one-eighth of an inch thick, after which it is rubbed down…. It is then polished with a crystal, or smooth stone rubber, and as soon as it has acquired a sufficient polish, a little very fine Bellapum powder is sprinkled upon it, to increase its whiteness and lustre, while the rubbing is still continued. The second coat ought to begun [sic] and finished in one day, unless in damp weather….

“For three coats.

… A day or two afterwards, before it has had time to dry, the third coat is applied. This consists of four parts of lime, and one of fine white sand; these, after being well mixed, are reduced by grinding to a very fine paste…. This is… mixed with the whites of eggs, tyre (curds), and ghee (butter), in the following proportions:-

12 eggs, 1½ measures of tyre and ½ lb. of ghee to every parah of plaster.

“These must all be thoroughly mixed… to a paste of a uniform consistence, a little thicker than cream, and perfectly free from grittiness…, and is put on about one-tenth of an inch thick, … when it is gently rubbed, till it becomes perfectly smooth. Immediately after this another coat of still finer plaster is applied, consisting of pure lime ground to a very fine paste, and afterwards mixed with water… until it is of consistency of cream. This is put on one-sixteenth of an inch thick, with a brush, and rubbed gently with a small trowel, till it becomes slightly hard it is then rubbed with the crystal or stone rubber, until a beautiful polish is produced, during which process the wall is occasionally sprinkled with fine Bellapum powder…

“If the plaster be not entirely dry on the second morning, the operation of polishing ought to be continued until it is quite dry. The moisture as before mentioned must be carefully wiped off, and the wall kept quite dry till all appearance of moisture ceases.”11

Holman’s and Vicat’s descriptions of how to mix the plaster, combined with our knowledge of the size of the church building, allow us to calculate approximately how much Madras chunam would have been needed to plaster the interior walls. According to McNair:

“[The] building is 250 feet long internally, by 65 feet in width, with nave and side aisles; or, with the north and south transepts, 95 feet, the transepts being used as porticoes.”12

Based on these dimensions, the interior walls have a linear run of 690 feet (250 by 95 feet) or approximately 210 m. With the height of the walls being approximately 50 feet (15.24 m), the approximate surface area of the interior walls would then be 34,500 sq ft (3,205 sq m). Vicat and Holman differed on the thickness of the final coat of Madras chunam used. The thickness ranges from one-tenth plus one-sixteenth of an inch, or approximately 4 mm, to one-quarter of an inch, or approximately 6 mm. The total volume of the final plaster would range approximately from 466 cu ft (13.2 cu m) to 718 cu ft (20.3 cu m).

Vicat and Holman also held different views on the number of eggs required to make the plaster. According to Vicat, around 10 to 12 eggs are needed per 1.28 cu ft, while Holman said that the whites of a dozen eggs were needed for every 2.17 cu ft.13 Based on these accounts, between 2,580 and 6,730 eggs would have been used to plaster the interior walls of St Andrew’s, which is a considerable number of eggs. This quantity does not account for the plaster on the columns.

| THE CURIOUS INGREDIENTS THAT MAKE UP MADRAS CHUNAM |

| When constructing a building, plaster is applied to the walls to protect the underlying stone or brick, and for decorative reasons. In the 19th-century, walls were typically plastered using lime plaster, which is primarily made of lime, sand and water. |

| Madras chunam, in contrast, uses additional ingredients. According to Louis-Joseph Vicat and James Holman, making Madras chunam also involved using ghee (butter) or oil, tyre (sour curd), albumen (egg white) and soapstone powder (lapis ollaris, commonly known as talc) in the final coat. |

| For lime, Vicat and Holman wrote that sea shells were used, while Frederick Aldophus McNair’s account cites corals instead. “[Our] lime… [was] made from coral, of which there were extensive reefs round the Island of Singapore…. Coral is almost a pure carbonate of lime, and therefore very well suited for the purpose. It was broken up and heated in kilns constructed for the purpose”.14 |

| It is not unusual to use raw sugar (jaggery) in plaster. In fact, sugar is widely used as an additive to increase the plasticity of lime plaster as it decreases the viscosity of plaster and improves its workability and strength. This quality is especially important in decorative plastering, such as mouldings and capitals. |

| Oil is also a common ingredient used in the final coat of plaster. In the West, linseed oil15 is typically used, while Tung oil16 is used in China. The addition of oil increases the plaster’s water resistance and is typically used in the final layer. |

| Soapstone powder consists of a large agglomerate of hydrated magnesium silicate that is used for polishing soft materials. |

| Sour curd is largely made up of milk proteins (casein), which are useful as a binder in lime plaster to improve its adhesive properties.17 Conceivably, as albumen comprises primarily of protein, it might also have been used as a binder. In recent years, studies have found that albumen does increase the compressive and flexural strength of plaster.18 |

| Coconut fibre in some form is cited as an ingredient by McNair though not by Vicat and Holman. It is unclear from McNair’s account if the lime plaster was mixed with water, together with the coconut fibre (husk) that was steeped in it, or just the water, with the husk removed. Coconut fibre is composed mainly of cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin, which are insoluble in water.19 Coconut fibre, however, is known to have been added to plaster to improve its tensile strength20 and it is not inconceivable that it was used in the mixture. |

A lime kiln at Kampong Mata Ikan, 1967. Seashells (white pile on the left), which are made of calcium carbonate, are heated to approximately 900 degrees Celsius to produce calcium oxide, also known as quicklime. The man is using a woven rattan pungki or pengki (畚箕) (a shallow basket) to deposit what looks to be charcoal – fuel for the kiln – into an open pit. Photo by Hor Kwok Kin. Retrieved from Photonico. A lime kiln at Kampong Mata Ikan, 1967. Seashells (white pile on the left), which are made of calcium carbonate, are heated to approximately 900 degrees Celsius to produce calcium oxide, also known as quicklime. The man is using a woven rattan pungki or pengki (畚箕) (a shallow basket) to deposit what looks to be charcoal – fuel for the kiln – into an open pit. Photo by Hor Kwok Kin. Retrieved from Photonico. |

Constructing St Andrew’s

The foundation stone of the present church building was laid by the Right Reverend Daniel Wilson, Lord Bishop of Calcutta and Metropolitan of India, on 4 March 1856.21 It was designed by Ronald MacPherson of the Madras Artillery, who was appointed Executive Engineer and Superintendent of Convicts in Singapore. He is said to have drawn inspiration for the design from a ruined Cistercian monastery in the village of Netley in Hampshire, a county in southeast England.22

When MacPherson left for Melaka in 1857 to take up a new posting as Resident Councillor, McNair took over the responsibility as Engineer and Superintendent of Convicts, and with the assistance of John Bennett, a civil and mechanical engineer, supervised the construction of the church carried out by Indian convict labourers.23

After five years of construction, an opening service was held on 11 October 1861.24 At the time, the interiors were almost completed but the exterior and the spire were still unfinished.25 The church was consecrated by the Bishop of Calcutta, George Edward Lynch Cotton, on 25 January the following year26 although the spire would only be completed in December 1864. Construction work on the entire building finally ended in April 1865, nine years after the foundation stone was laid.27

The construction of St Andrew’s faced funding constraints from the very beginning, which affected the building schedule. In an 1855 letter, Edmund Augustus Blundell, then Governor of the Straits Settlements, wrote to the Secretary to the Government of India, outlining the budget and the reliance on convict labour to keep costs down:

“Original estimate sanctioned in 1853 amounting to Rs. 14,985 is now, of course, wholly inadequate to effect the construction of the entire New Building suited to accommodate the large and increasing Protestant Congregation of the place… Captain Macpherson’s estimate, amounts to 120,932 Rs, but with the assistance of Convict labor, and chiefly of materials prepared by Convict labor, he reduces the actual outlay to 47,916 Rs. and I have no doubt, that by venturing on Convict labour to a still greater extent, as mentioned by him in his letter accompanying the Plan and Estimate; the Estimate of the actual outlay of money may be reduced to 40,000 Rs…”28

Funding remained tight throughout the entire building process. In 1859, three years into its construction, the government tried to raise funds to complete the spire through loans from public subscribers.29 Three years later, The Singapore Free Press reported that “Rs. 21,784 was spent on St Andrew’s Church; the body of this fine building was completed” while “the spire is in abeyance”.30 This suggests that the project may not have been allocated the Rs. 40,000 estimated by Blundell.

Work progressed slowly over the next few years.31 In 1863, the tower with eight pinnacles, on which the base of the spire would be constructed, was built.32 It would take another two years before the spire was finally erected, signifying the completion of the handsome English gothic edifice.33 (The original design of the spire could not be realised and the spire was redesigned by Jasper Otway Mayne, an engineer in the Public Works Department.) In total, the construction of the church took nine years: five years to complete the main building and interiors, and another four for the tower and spire.

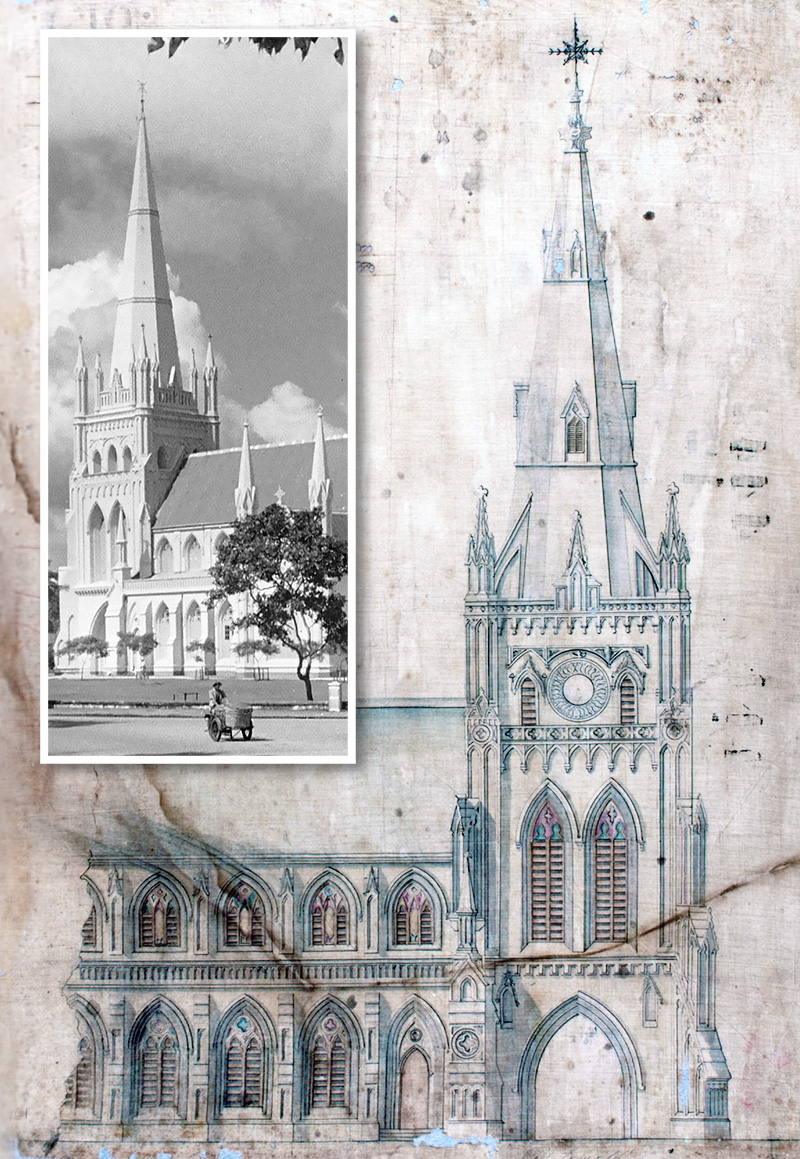

This elevation drawing of the proposed spire design for St Andrew’s Church (now St Andrew’s Cathedral) is attributed to Ronald MacPherson. However, his design was not realised and a simplified design (see inset photo) by Jasper Otway Mayne, an engineer with the Public Works Department, was constructed instead. Among the many differences, the oeil-de-boeuf (bull’s eye) windows at the belfry level were replaced by lancet windows, and the flying buttresses connecting the pinnacles to the spire, as well as lucarne (spire light), which is a type of dormer window, were removed. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board..

This elevation drawing of the proposed spire design for St Andrew’s Church (now St Andrew’s Cathedral) is attributed to Ronald MacPherson. However, his design was not realised and a simplified design (see inset photo) by Jasper Otway Mayne, an engineer with the Public Works Department, was constructed instead. Among the many differences, the oeil-de-boeuf (bull’s eye) windows at the belfry level were replaced by lancet windows, and the flying buttresses connecting the pinnacles to the spire, as well as lucarne (spire light), which is a type of dormer window, were removed. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board..

One of the casualties of the tight funding was the plastering work. In 1859, The Singapore Free Press wrote that because the “proposal of a Government Loan for the completion of the Church has not produced any favourable effect… not a single man is now allowed to work there – that the small number of Convicts allowed for plasterers of the interior have been withdrawn”.34

Putting It All Together

We know from Holman’s account that the production process for the plaster – from preparation and application to completion, especially for the final finishing coat – is both laborious and labour-intensive. Given the challenges of limited funds and a labour shortage, it is certainly possible that Madras chunam was not used at all, or if it was, only in a very limited fashion.

Some other clues emerged from newspaper archives. In 1949, the cathedral had to undergo major repair work as the structure had suffered damage during the Japanese Occupation (1942–45) when it was used as a hospital.35 A 1949 article in The Malayan Tribune reported that the “original walls of ‘Madras chunam’… are being replaced by plaster…” and that the colour scheme would be changed from grey to white on the interiors and grey on the exterior.36

Based on this account, the interior of the church in 1949 was grey before the repair work. The key point to note is this: if the church’s interior was indeed executed in Madras chunam as McNair had asserted, the colour is unlikely to be grey. This is because only the purest and whitest of shells are used in the production of Madras chunam, and great care is taken to ensure its pristine whiteness. As such, the mention of the grey interior walls suggests that the walls were not plastered with Madras chunam when the building was first built, or possibly, that the material was replaced at some point thereafter.

In the absence of any physical confirmation or other published documentation to confirm the presence of Madras chunam in St Andrew’s, the only evidence for it then is McNair’s account. Could McNair be mistaken? His book, Prisoners Their Own Warders, was published in 1899, some 34 years after the completion of the church, so a faulty memory cannot be ruled out.

An alternative explanation is that Madras chunam was indeed used as described by McNair, but only in a very limited fashion because of budgetary constraints.

Without a comprehensive examination, we cannot know with any certainty if Madras chunam was actually used in St Andrew’s. And even if we were able to conduct comprehensive experiments that returned negative results, there is still a possibility that Madras chunam was used initially, but subsequently removed.

Having weighed the historical evidence – the budgetary constraints that affected the progress of construction and the grey walls in 1949 – and given the results of the trials and repairs conducted in the last decade, there is sufficient evidence to say that Madras chunam was never actually used in St Andrew’s. Regrettably, however, we will never know for sure.

| The author would like to acknowledge Wee Sheau Theng for her invaluable assistance in the course of this research. |

Dr Yeo Kang Shua is Associate Professor of Architectural History, Theory and Criticism, and Associate Head of Pillar (Research/Practice/Industry) at the Singapore University of Technology and Design.

Dr Yeo Kang Shua is Associate Professor of Architectural History, Theory and Criticism, and Associate Head of Pillar (Research/Practice/Industry) at the Singapore University of Technology and Design.

NOTES

-

St Andrew’s Cathedral is the second church building on the site of the original St Andrew’s Church, named after the patron saint of Scotland. The original building was designed by Government Superintendent of Public Works George D. Coleman and completed in 1836. After the spire of the church had been struck by lightning in 1845 and 1849, the building was considered unsafe and later demolished. The second St Andrew’s Church was completed in 1865. It was consecrated as a cathedral in 1870 and became known as St Andrew’s Cathedral. See Cornelius-Takahama, V. (2017). St Andrew’s Cathedral. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia, National Library, Singapore. ↩

-

McNair, J.F.A., & Bayliss, W.D. (1899). Prisoners their own warders: A record of the convict prison at Singapore established 1825, discontinued 1873, together with a cursory history of the convict establishments at Bencoolen, Penang and Malacca from the Year 1797. Westminster: A. Constable. (Call no.: RRARE 365.95957 MAC; Microfilm no.: NL12115) ↩

-

McNair & Bayliss, 1899, pp. 98–100. ↩

-

Town and country. (1928, July 7). The Straits Times, p. 10; Cathedral bells silent for first time in fifty years. (1936, March 29). The Straits Times, p. 28; Cathedral’s walls were coated with egg. (1949, September 13). The Malaya Tribune, p. 2; Davies, D. (1954, October 24). Convicts and the whites of eggs. The Straits Times, p. 14; The hazards of photography 100 years ago. (1957, July 7). The Straits Times, p. 12; St. Andrew’s Cathedral. (1971, September 17). New Nation, p. 9; Chandy, G. (1979, December 3). Christmas was special event even then. New Nation, p. 9; Chia, A. (1981, July 19). Peace and quiet pervades its grounds. The Straits Times, p. 4; Teh, J.L. (2003, June 5). Fewer cars might help this building last longer. The New Paper, p. 4; Ng, J.X. (2013, April 2). White church, colourful past. The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Liu, G. (1996). In granite and chunam: The national monuments of Singapore (p. 174). Singapore: Landmark Books and Preservation of Monuments Board. (Call no.: RSING 725.94095957 LIU); Tan, B. (2015, October–December). Convict labour in colonial Singapore. BiblioAsia, 11 (3), pp. 36–41. Retrieved from BiblioAsia website. ↩

-

Keys, P. (1981, June 14). Terrace houses. The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Edwards, N., & Keys, P. (1988). Singapore: A guide to buildings, streets, places (p. 114). Singapore: Times Books International. (Call no.: RSING 915.957 EDW) ↩

-

Toh, W.L. (2017, November 2). Once upon a glorious time at the Istana. The Straits Times, p. 15. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

McNair & Bayliss, 1899, pp.103–104. ↩

-

Zaccheus, M. (2016, November 17). Caring for a 154-year-old Matriarch. The Straits Times, p. 14. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Vicat, L.-J. (1837). A practical and scientific treatise on calcareous mortars and cements, artificial and natural (p. 176). London: John Weale. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Holman, J. (1840). Travels in Madras, Ceylon, Mauritius, Cormoro Islands, Zanzibar, Calcutta, etc. etc (pp. 420–425). London: George Routledge. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

McNair & Bayliss, 1899, pp. 98–100. ↩

-

Treese, S.A. (2018). History and measurement of the base and derived units (p. 429). Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

McNair & Bayliss, 1899, p. 111. ↩

-

Tesi, T. (2009). The effect of linseed oil on the properties of lime-based restoration mortars [Unpublished PhD thesis]. Universita di Bologna. Retrieved from Core website; Nunes, C., & Slizkova, Z. (2014, July–August). Hydrophobic lime-based mortars with linseed oil: Characterization and durability assessment. Cement and Concrete Research, 61–62, 28–39; Nunes, C., et al. (2018, November 20). Influence of linseed oil on the microstructure and composition of lime and lime-metakaolin pastes after a long curing time. Construction and Building Materials, 189, 787–796. Retrieved from ResearchGate. ↩

-

Fang, S., et al. (2014, January). A study of Tung-oil-lime putty – A traditional lime-based mortar. International Journal of Adhesion and Adhesives, 48, 224–230; Zhao, P., et al. (2015, June). Material characteristics of ancient Chinese lime binder and experimental reproductions with organic admixtures. Construction and Building Materials, 84, 477–488. Retrieved from ResearchGate. ↩

-

Ventola, L. et al. (2011, August). Traditional organic additives improve lime mortars: New old materials for restoration and building natural stone fabrics. Construction and Building Materials, 25 (8), 3313–3318. Retrieved from ResearchGate. ↩

-

Md Azree Othuman Mydin. (2017, October). Preliminary studies on the development of lime-based mortar with added egg white. International Journal of Technology, 8 (5), 800–810, p. 800; Md Azree Othuman Mydin. (2018). Physico-mechanical properties of lime mortar by adding exerted egg albumen for plastering work in conservation work. Journal of Materials and Environmental Sciences, 9 (2), 376–384. Retrieved from ResearchGate. ↩

-

Rencoret, J., et al. (2013, March). Structural characterization of lignin isolated from coconut (Cocos nucifera) coir fibers, Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 61 (10), 2434–2445. Retrieved from ResearchGate. ↩

-

Navaratnarajah, S., et al. (2017, July 1). Performance of coconut coir reinforced hydraulic cement mortar for surface plastering application. Construction and Building Materials, 142, 23–30. Retrieved from ResearchGate. ↩

-

Untitled. (1856, March 4). The Straits Times, p. 4; St. Andrews. (1870, April 30). The Straits Times, p. 1; Untitled. (1870, December 24). The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Straits Times Saturday, Oct. 12, 1861. (1861, October 12). The Straits Times, p. 19. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; McNair & Bayliss, 1899, pp. 71–74, 97. ↩

-

McNair & Bayliss, 1899, pp. 71–74, 97; The Straits calendar and directory for 1861 (pp. 26–27). (1861). Singapore: Printed at the Commercial Press. Retrieved from BookSG. In the Straits Times article, John Bennett was named the Executive Engineer while J.F.A. McNair was not mentioned. However, in McNair’s Prisoners Their Own Warders, it is mentioned that a Captain Purvis of the Madras Artillery had succeeded MacPherson in the role of Engineer and Superintendent of Convicts in 1857 but relinquished his position a year later. McNair then succeeded him, while Bennett was Assistant Superintendent of Convicts. Upon verification with The Straits Calendar and Directory for 1861, McNair was on leave in Europe and Bennett, who held the positions of Special Assistant Engineer and Deputy Superintendent of Convicts, was thus officiating as both the Executive Engineer and the Superintendent of Convicts in McNair’s absence. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 12 Oct 1861, p. 19. It is interesting to note, however, that the church was recorded as opened for service on 6 October 1861 in The Straits Calendar and Directory for 1861. See The Straits calendar and directory for 1861, 1861, p. 42. ↩

-

During construction, the original design of the spire by Ronald MacPherson was deemed unsuitable due to supposed settlement issues and thus said to have been redesigned by Jasper Otway Mayne, an engineer with the Public Works Department. See The Straits Times, 24 Dec 1870, p. 1. ↩

-

McNair & Bayliss, 1899, p. 74; The Straits calendar and directory for 1863 (p. 20). (1863). Singapore: Printed at the Commercial Press. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press: Notes on the annual report on the administration of the Straits Settlement for the year 1864–65. (1865, August 31). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; The Straits calendar and directory for 1865 (p. 21). (1865) Singapore: Printed at the Commercial Press. Retrieved from BookSG; The Straits Times, 24 Dec 1870, p. 1. ↩

-

Blundell, E.A. (1856, May 6). The editor’s room. The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Correspondence: Government loan. (1859, August 25). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Page 3 Advertisement Column 1: Ecclesiastical. (1862, June 26). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 12 Oct 1861, p. 19; Singapore: Saturday, 12 Nov. 1859. (1859, November 12). The Straits Times, p. 2; News of the Week. (1863, April 11). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

St. Andrew’s Church. (1863, October 17). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press, 31 Aug 1865, p. 2. ↩

-

Correspondence. (1859, September 8). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore on February 15, 1942. (1946, February 15). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Malaya Tribune, 13 Sep 1949, p. 2; Lim, S.J. (1996, November 30). Places of worship steeped in history. The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩