Stories From the Stacks

A book of football rules in Jawi, a colonial-era compilation of Tamil names and the 19th-century version of a 600-year-old Chinese map showing Temasek are among the items showcased in Stories from the Stacks, the latest book published by the National Library, Singapore.

A Football Rulebook in Jawi

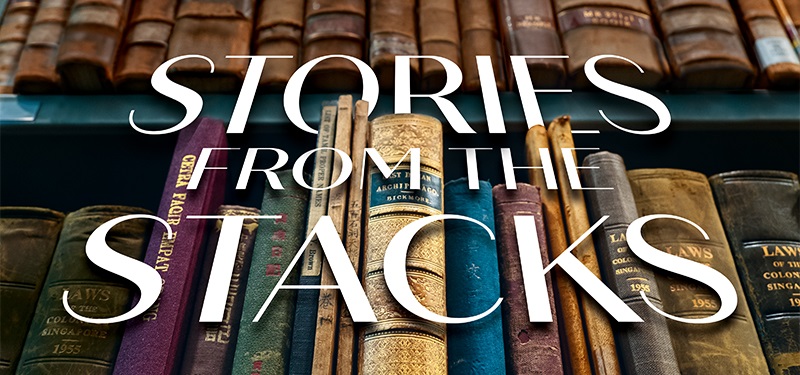

| Title: Inilah Risalat Peraturan Bola Sepak yang Dinamai oleh Inggeris Football (A Book of Football Rules) Author: Mahmud ibn Almarhum Sayyid Abdul Kadir al-Hindi (translator) Year published: 1895 Publisher: Lembaga Keadilan (Committee) Persekutuan Dar al-Adab Language: Malay (Jawi script) Type: Booklet, 16 pages with a fold-out plan of a football field Call no.: RRARE 796.334 FOO Accession no.: B21189180H |

Although it is not clear exactly when the football-loving British introduced the game to Malaya, it became so popular among Malay youths here that a guide to the sport was published by the Ethical Committee of the Dar al-Adab Association1 in 1895. Printed by the American Mission Press in Singapore, Inilah Risalat Peraturan Bola Sepak yang Dinamai oleh Inggeris Football (henceforth referred to as Risalat Peraturan Bola Sepak) covers the rules of the game over 17 topics (bab) in Jawi – the Arabic script adapted for writing the Malay language.

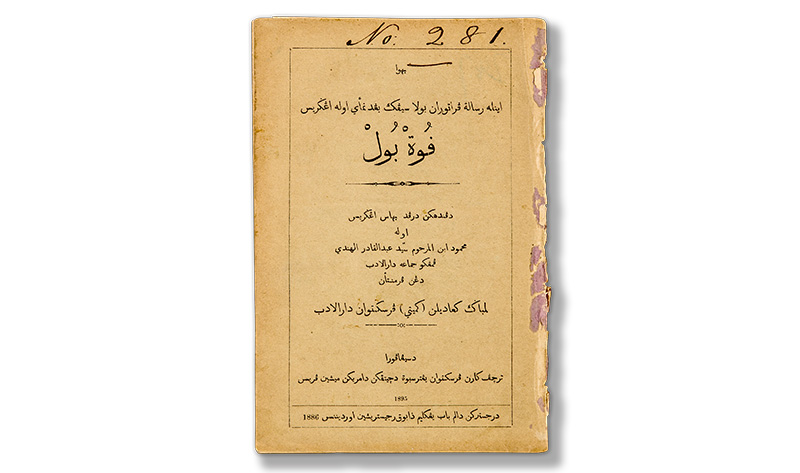

The title, author, publisher and printer of the booklet are stated on the front cover. Inside the 16-page booklet is a fold-out plan of a football field with the positions of the players indicated in Jawi. Below the diagram are Jawi references to player positions, accompanied by their English equivalents. With the exception of the fold-out plan and a glossary of terms where the corresponding English explanations such as “off-side” and “free kick” appear next to the Jawi phrases, everything else in Risalat Peraturan Bola Sepak is written in Jawi.

At the bottom of the cover page of Risalat Peraturan Bola Sepak is a line indicating that the booklet is registered under Chapter Five of the Book Register Ordinance 1886. Collection of the National Library, Singapore.

At the bottom of the cover page of Risalat Peraturan Bola Sepak is a line indicating that the booklet is registered under Chapter Five of the Book Register Ordinance 1886. Collection of the National Library, Singapore.

It is not known which English source (or sources) the writer, Mahmud ibn Almarhum Sayyid Abdul Kadir al-Hindi, used as a reference to produce this book of football rules. In the foreword, Mahmud writes that arguments and disputes on the playing field became commonplace as more Malays took to the game. Seeing the need to explain the basic rules of football to new enthusiasts, the Dar al-Adab Association commissioned him to write the book.

Although Mahmud was well versed in Malay linguistics – between 1881 and 1918, he was involved as either the author or translator of 16 Malay works, including a Malay dictionary (Kamus Mahmudiyyah) – he admitted in the foreword that the task of translating football rules from English to Malay was challenging.

To make the text clearer, he used basic English terms that Malay players were already familiar with, such as “goal”, “corner” and “free kick”. Even so, Mahmud was dissatisfied with his attempt and, in his foreword, expressed hopes of producing a more detailed book on football rules in future. However, to date, no other football-related book authored by Mahmud has ever been found.

Another key person involved in the publication was Haji Muhammad Siraj bin Haji Salih. He was an accomplished copyist-editor, a prolific printer and the biggest bookseller of Muslim publications in Singapore in the late 19th century. As the Honorary Secretary of Dar al-Adab, Haji Muhammad Siraj was instrumental in engaging the services of the American Mission Press to print Mahmud’s work.2 Copies of the booklet were sold at Haji Muhammad Siraj’s shop at 43 Sultan Road.3 When he passed away in 1909, The Straits Times described him as “one of the best known of the Malays of Singapore”.4

The booklet includes a fold-out plan with positions of players labelled in Jawi on the diagram of a football field. Collection of the National Library, Singapore.

The booklet includes a fold-out plan with positions of players labelled in Jawi on the diagram of a football field. Collection of the National Library, Singapore.

Dar al-Adab, the publisher of Risalat Peraturan Bola Sepak, was one of the earliest Malay/Muslim recreation clubs in Singapore. The club was established in 1893 and had its own grounds in Jalan Besar, where it held sports events that were well attended by locals and Europeans.5 Dar al-Adab likely had a vested interest in commissioning the book of football rules as it was the organiser of the annual football competition called the Darul Adab Cup. Several recreation clubs and local football teams competed for this trophy.6

Interestingly, the British regarded football as a tool to “civilise” the “ignorant” “natives” living in its colonies.7 An 1894 report in The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser noted in rather grandiose terms:

“All these native races have readily taken to various forms of athletic sport, and the sight of men of every race, colour and creed assembled together on the cricket or football field, afford striking evidence of the good results attending British protection, whilst the mere assembly for a common purpose by teaching men of different races to know and respect one another exercises a by no means unimportant influence on their general civilisation”.8

It is debatable whether football had any civilising effect on the “men of different races” in Singapore. What is more certain is that Risalat Peraturan Bola Sepak was helpful in teaching Malay youths the basic rules of the game.9 More than a century after its publication, the sport remains hugely popular, not just among Malays in Singapore, but for all communities.

Football (or soccer) in the form played today can be traced to mid-19th-century England, although the actual history of the game goes back more than 2,000 years. Image reproduced from Shearman, M. (1887). Athletics and Football (p. 345). London: Longmans, Green, and Co. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons.

Football (or soccer) in the form played today can be traced to mid-19th-century England, although the actual history of the game goes back more than 2,000 years. Image reproduced from Shearman, M. (1887). Athletics and Football (p. 345). London: Longmans, Green, and Co. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons.

A Book of Tamil Names

| Title: List of Tamil Proper Names Author: Alfred Vanhouse Brown Year published: 1904 Publisher: Government Printing Office (Kuala Lumpur) Language: Tamil, English Type: Book, 48 pages Call no.: RRARE 929.4 BRO Accession no.: B16331012F |

In governing a diverse population that spoke and wrote a variety of languages, the British colonial administrators in Singapore and Malaya faced many challenges. The languages used in Malaya, China and India have their own writing systems, none of which were remotely similar to the Latin script familiar to the British. This would have made the identification of individuals, with their names rendered in different scripts, a problem. To overcome this, the colonial government commissioned the compilation of lists containing the romanised versions of common Asian names.

One such document used by colonial officials to transcribe Tamil names10 is the 48-page List of Tamil Proper Names, published in Kuala Lumpur in 1904. Although this was neither the first nor the longest list produced by the Government Printing Office of the Federated Malay States, the personal and caste names in the book shed light on the patterns of Indian migration into British Malaya during the 19th and early 20th centuries.

The Indian subcontinent is home to numerous ethno-linguistic groups. Of these, South Indians formed the largest segment of the Indian immigrant population in British Malaya, particularly from the late 19th century onwards. The Tamils, most of whom were employed as labourers in plantations, the harbour, and transportation and municipal sectors, constituted the majority of these migrants,11 with smaller groups of Malayalees and Telugus.12 This explains why the British saw the need to commission a book of specifically Tamil names.

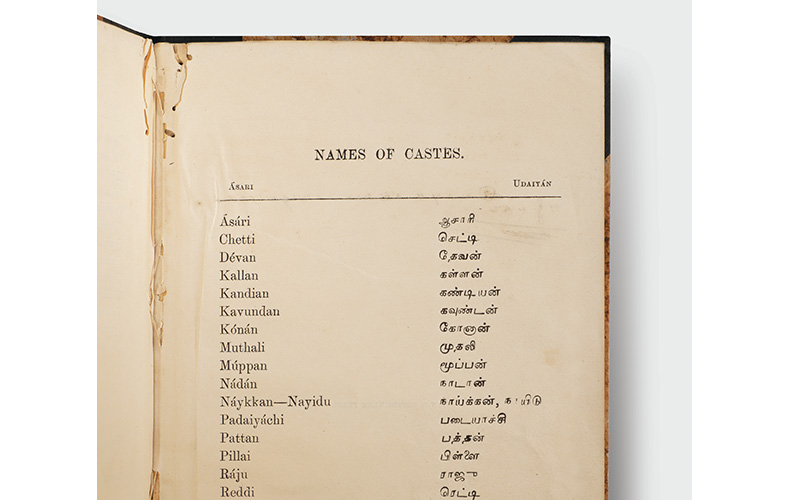

A glimpse of the personal and caste names used by the Tamil community in British Malaya. The list was collated by colonial officer Alfred Vanhouse Brown and A. Swaminatha Pillai, an intrepreter of Tamil and Hindi languages from Perak. Interestingly, some caste names in the booklet, such as “Nayidu” and “Reddi”, are typically associated with the Telugu community, rather than Tamils. Collection of the National Library, Singapore.

A glimpse of the personal and caste names used by the Tamil community in British Malaya. The list was collated by colonial officer Alfred Vanhouse Brown and A. Swaminatha Pillai, an intrepreter of Tamil and Hindi languages from Perak. Interestingly, some caste names in the booklet, such as “Nayidu” and “Reddi”, are typically associated with the Telugu community, rather than Tamils. Collection of the National Library, Singapore.

Alfred Vanhouse Brown, an officer with the Federated Malay States Civil Service who was based in Kuala Lumpur, compiled the list with the assistance of A. Swaminatha Pillai, an interpreter of Indian languages from Batu Gajah, Perak.13

Brown was educated at the Merchant Taylor’s School in London and Queen’s College in Oxford, graduating with a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1896. That year, he was appointed to serve in the Eastern Cadetships, specifically the civil service in the Federated Malay States. He undertook several positions there until 1906, when he was appointed Superintendent of Posts and Telegraphs in Selangor, Negri Sembilan and Pahang. In the same year, Brown also served as the Acting District Officer and Indian Immigration Agent in Perak.14

There is not much more information about Brown and Pillai, or how they collated the names. According to the note at the front of the book, Brown adhered closely to the transliteration system laid down by the Board of Revenue in Madras, Tamil Nadu.15 He also provided a useful guide to help readers pronounce vowels in the romanised Tamil names by using corresponding vowel sounds found in English words.

Page 1 (unnumbered) to page 45 of the book contain the romanised spellings of common Tamil personal names. This list is organised in alphabetical order, alongside a column that indicates if the names belong to men (labelled “M”) or women (“F”). The third column contains the corresponding names written in Tamil script.

On the last page of the book is a list of 19 caste names, most of which belong to those from the upper castes, including widely recognised names such as “Chetti” and “Pillai”.16 The former, for instance, refers to the Chettiar community, a Tamil trading caste of businessmen and moneylenders. The Chettiars who migrated to British Malaya consisted mainly of the Nattukottai Chettiars, a subgroup involved principally in moneylending,17 and who later became a key fixture of the business landscape in British Malaya.

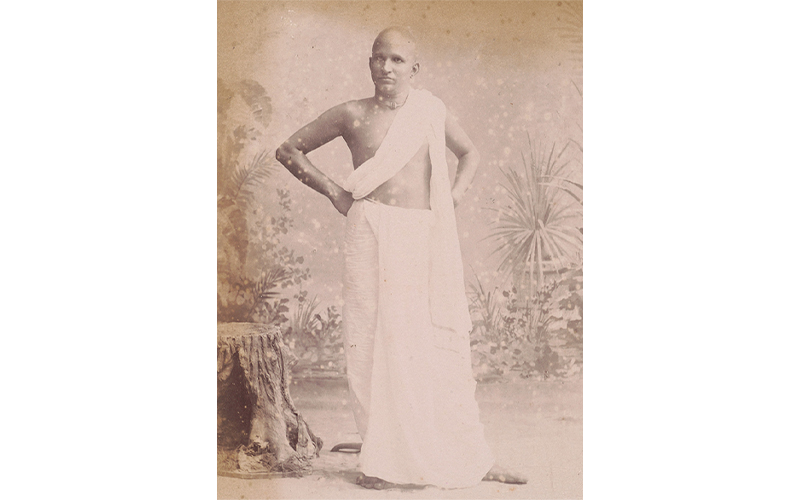

A Chettiar moneylender, c. 1890. Originally from South India, the Chettiars started coming to Singapore during the 19th century. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

A Chettiar moneylender, c. 1890. Originally from South India, the Chettiars started coming to Singapore during the 19th century. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

Interestingly, some of the caste names in the list, such as “Nayidu” and “Reddi”, are typically associated with the Telugu community rather than the Tamils. Both names may have been used by Telugu migrants who moved from the coastal districts of Andhra Pradesh to Tamil Nadu, before migrating to British Malaya. Over time, these immigrants from various castes and linguistic groups who settled in Tamil Nadu may have adopted the language and cultural practices of the Tamils.18

Names provide a window into an individual’s identity – whether it be gender, ethnicity, religious affiliation, nationality or social position. For instance, Tamil names traditionally do not carry a family name. Instead, both males and females use their father’s name before their personal name. Upon marriage, a Tamil woman would traditionally adopt her husband’s personal name in place of her father’s name.

The List of Tamil Proper Names is a useful historical source for reseaching the migration and settlement history of Singapore’s Tamil community. It also complements similar publications in the National Library that list the common names of members of the Malay and Chinese communities in the Straits Settlements.

Admiral Zheng He’s Navigation Map

| Title: Mao Kun Map (茅坤图), from Wu Bei Zhi (武备志), Chapter 240 Compiler: Mao Yuanyi (茅元仪) Year published: Late 19th century Language: Chinese Type: Map Call no.: RRARE 355.00951 WBZ Accession no.: B26078782G Donated by: Singapore Federation of Chinese Clan Associations |

The Mao Kun Map (茅坤图) is the collective name for a set of navigational maps that are based on the 15th-century expeditions of the Indian Ocean by renowned Ming dynasty explorer Admiral Zheng He (郑和; 1371–1433/35).

Also known as Zheng He’s Navigation Map (郑和航海图) or the Wu Bei Zhi Chart, the map is believed to have been drawn between 1425 and 1430, although scholars have offered differing views of its exact date of origin.19 The term Mao Kun Map, as coined by the Dutch sinologist Jan Julius Lodewijk Duyvendak (1889–1954), is the most commonly used name today for this set of Chinese navigational maps.

The Mao Kun Map was first published in the late-Ming publication Wu Bei Zhi (武备志).20 It was compiled in 1621 by Mao Yuanyi (茅元仪; 1594–1640), who served as a strategist in the Ming court, and published in 1628. Mao’s grandfather, Mao Kun (茅坤; 1512–1601), owned a large and distinguished personal library, and it is believed that this map was part of his collection. Given that three generations of the Mao family had served in the Ming dynasty’s imperial service – either in a military or naval capacity – it is not surprising that the map ended up in their possession.

Originally drawn as a scroll measuring 20.5 cm by 560 cm (in the manner of traditional Chinese paintings), which no longer exists today, the Mao Kun Map was recast into 40 pages – essentially an atlas format – for publication in the 240-chapter Wu Bei Zhi. The map is featured in the final chapter of the Wu Bei Zhi, in the “Geographical Surveys” section, which covers astronomical observations and geographical surveys for military operations. After more than 250 years of obscurity, the Mao Kun Map was made known to the rest of the world around 1885–86 in a journal article by George Phillips (1836–96).21

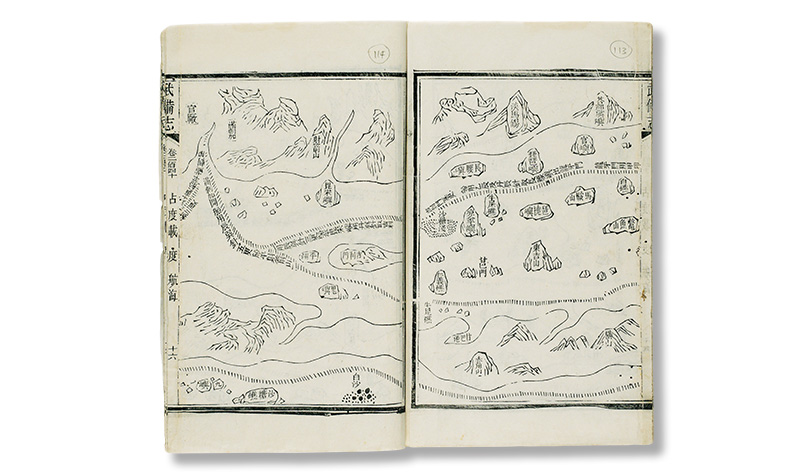

The Mao Kun Map is believed to be based on the naval expeditions of the early 15th-century Ming admiral, Zheng He, who made several voyages from China to Southeast Asia and across the Indian Ocean. The pages shown here depict the return route between Melaka and China through the Strait of Singapore. The name Temasek (淡马锡), is marked on a hill on the right page. Pedra Branca (白礁) appears on the same page, whereas Melaka (满剌加) is labelled at the top left of the left page. Collection of the National Library, Singapore.

The Mao Kun Map is believed to be based on the naval expeditions of the early 15th-century Ming admiral, Zheng He, who made several voyages from China to Southeast Asia and across the Indian Ocean. The pages shown here depict the return route between Melaka and China through the Strait of Singapore. The name Temasek (淡马锡), is marked on a hill on the right page. Pedra Branca (白礁) appears on the same page, whereas Melaka (满剌加) is labelled at the top left of the left page. Collection of the National Library, Singapore.

The National Library’s copy of the Mao Kun Map is from a late 19th-century edition of the Wu Bei Zhi. It is among one of six known editions of the Wu Bei Zhi published over the centuries. All six editions are still extant and held in various private and public collections around the world, but it is not known how many copies there are of each.

The navigational map is read from right to left in the tradition of classical Chinese writing and painting. The voyage begins at the Treasure Ship factory near the Ming capital city of Nanjing and follows a southerly course along the coast of China for 19 pages until it reaches Chiêm Thành in Vietnam. It then continues to various places in Southeast Asia over the next 12 pages, before reaching Martaban in Myanmar. The last nine pages depict the routes to Ceylon (Sri Lanka), India, Arabia and the east coast of Africa. The furthest point reached on the map is Malindi in Kenya.

The Mao Kun Map was conceived and drawn as a strip map, with the sailing route taking centre stage and the geographical features rendered in a linear fashion along the sailing route. As such, both the orientation and scale vary from one segment to the next on the map, leading to a “distortion” of space as we generally understand it.

To further compound the difficulty of interpreting the map, upon reaching the Southeast Asian archipelago, the journeys no longer progress in a linear route. From this point onwards, the map has to be read as two distinct parts: the upper half of each page depicting one journey, and the lower half presenting a separate and unrelated journey. Both narratives continue onto the subsequent pages – but at different travel speeds. In order to understand the map better, the two halves have to be interpreted separately.

While land masses and islands are depicted in plan view (i.e. bird’s-eye view), the major cities and mountains are portrayed in elevation view (i.e. like cardboard stand-ups). The sailing routes are shown as dashed lines, while important places like settlements and landmarks are labelled. Altogether, some 500 place names appear on the map, with the most prominent place names – such as countries, provinces and prefectures, and official installations like forts or depots – boxed up.

The Mao Kun Map uses two navigational techniques. The first is the Chinese 24-point compass, with 15 degrees for each compass point or “needle” (or compass needle) employed throughout the map. The second is the “star altitude” technique (过洋牵星术), which navigators once used to cross the Indian Ocean. This technique made use of the known altitude of selected stars and compared them with markings on a reference board. If the altitude of a selected star matched a certain pre-marked altitude line on the reference board, the exact position and location of the ship could be determined.

In order to achieve this feat, the people living along the coasts of the Indian Ocean would have been called upon to assist with this type of navigation. Four pages of “star altitudes” are appended at the end of the Mao Kun Map.

Of interest is the fact that the name Temasek (淡马锡) appears at the top centre of page 27, while Melaka (满剌加) appears at the top left of page 28. Other familiar places on page 27 as identified by scholar J.V.G. Mills include Pulau Sakijang Pelepah22 (琵琶屿), Pulau Tembakul23 (官屿/龟屿岛), Pulau Satumu24 (长腰屿) and Pedra Branca25 (白礁).

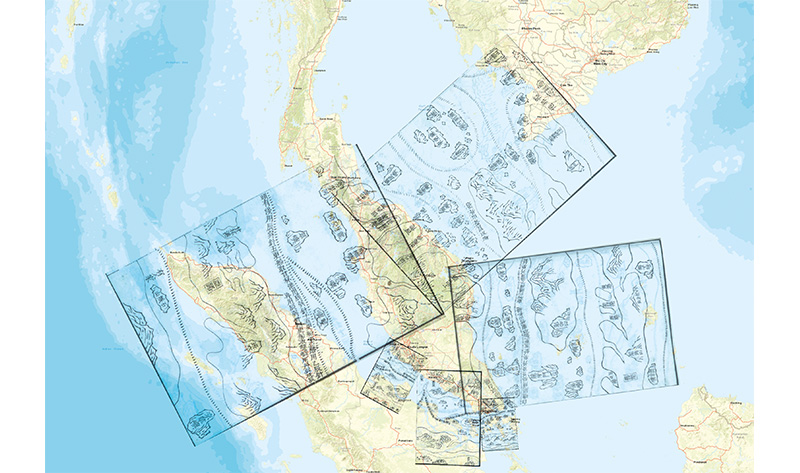

Overlay of six pages from the Mao Kun Map over a contemporary map of the Malay Peninsula. Image overlay provided by Mok Ly Yng.

Overlay of six pages from the Mao Kun Map over a contemporary map of the Malay Peninsula. Image overlay provided by Mok Ly Yng.

The sailing directions radiating from Melaka depict the homeward journey from Melaka to China across the South China Sea. The route passes through Karimun (吉利门) and to the South China Sea via Longyamen (龙牙门), or Dragon’s Teeth Gate, which was a significant navigational landmark in those days. Longyamen as indicated on the map refers to the main Strait of Singapore.

A depiction of Longyamen (Dragon’s Teeth Gate) by an unknown artist, c. 1848.

A depiction of Longyamen (Dragon’s Teeth Gate) by an unknown artist, c. 1848.

The Mao Kun Map is of great significance to Singapore as it is the only known cartographic work that mentions “Temasek” – the name that was used in ancient documents to indicate the site of modern Singapore. Other place names on the map have helped to narrow the location of Temasek to an area consistent with where Singapore is found today. There is, however, uncertainty over what exactly Temasek means on the map – does it refer to the island itself or to a larger region encompassing the island?

What is certain from the Mao Kun Map is that the Singapore Strait was used as a sailing route between the Indian Ocean and China in the 15th century, testifying to the importance of Singapore’s location in the regional trade network during this period.

These extracts are reproduced from Stories from the Stacks: Selections from the Rare Materials Collection, National Library Singapore. This recently published book features a small selection of some 19,000 items that form the library’s Rare Materials Collection. Spanning five centuries, with a special focus on Singapore and Southeast Asia, the collection comprises books, manuscripts, maps, photographs, letters, documents and other paper-based artefacts that offer invaluable insights into the history of Singapore and the region. Published by the National Library Board, Singapore, and Marshall Cavendish Editions, the book is available for reference at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and for loan at selected public libraries (Call nos.: RSING 016.95957 SIN-[LIB] and SING 016.95957 SIN) as well as for digital loan at nlb.overdrive.com. It is also available for sale at major bookshops in Singapore.

These extracts are reproduced from Stories from the Stacks: Selections from the Rare Materials Collection, National Library Singapore. This recently published book features a small selection of some 19,000 items that form the library’s Rare Materials Collection. Spanning five centuries, with a special focus on Singapore and Southeast Asia, the collection comprises books, manuscripts, maps, photographs, letters, documents and other paper-based artefacts that offer invaluable insights into the history of Singapore and the region. Published by the National Library Board, Singapore, and Marshall Cavendish Editions, the book is available for reference at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and for loan at selected public libraries (Call nos.: RSING 016.95957 SIN-[LIB] and SING 016.95957 SIN) as well as for digital loan at nlb.overdrive.com. It is also available for sale at major bookshops in Singapore.

Mazelan Anuar is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore, whose research interests are in early Malay publishing and digital librarianship.

Mazelan Anuar is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore, whose research interests are in early Malay publishing and digital librarianship.

Liviniyah P. is a former Associate Librarian with the National Library, Singapore, working with the Singapore and Southeast Asia collections.

Liviniyah P. is a former Associate Librarian with the National Library, Singapore, working with the Singapore and Southeast Asia collections.

Mok Ly Yng is a map research consultant with more than 20 years of experience. He has provided mapping consultancy to several map exhibitions, books and heritage projects.

Mok Ly Yng is a map research consultant with more than 20 years of experience. He has provided mapping consultancy to several map exhibitions, books and heritage projects.

NOTES

-

Also spelt “Daral Adab” and “Darul Adab”. ↩

-

Proudfoot, I. (1993). Early Malay printed books: A provisional account of materials published in the Singapore-Malaysia area up to 1920, noting holdings in major public collections (p. 41). Kuala Lumpur: Academy of Malay Studies and the Library, University of Malaya. (Call no.: RSING 015.5957 PRO) ↩

-

Proudfoot, I. (1987, December). A nineteenth-century Malay bookseller’s catalogue. Kekal Abadi, 6 (4), pp. 6, 8. Retrieved from Malay Concordance Project website. ↩

-

Social and personal. (1909, October 29). The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Darul Adab athletic sports. (1900, June 21). The Singapore Free Press, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Darul Adab Cup. (1900, October 8). The Straits Times, p. 15. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Cho, Y., & Little, C. (Eds.). (2015). Football in Asia: History, culture and business (p. 19). Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. (Call no.: RSEA 796.334095 FOO) ↩

-

Selangor in 1894. (1895, July 15). The Singapore Free Press, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Cho & Little, 2015, p. 19. ↩

-

Sandhu, K.S. (2010). Indians in Malaya: Immigration and settlement (1786–1957) (p. 15). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (Call no.: RSEA 325.25409595 SAN) ↩

-

Sinnappah, A. (1979). Indians in Malaysia and Singapore (pp. 44–45). Kuala Lumpur; New York: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 325.25409595 ARA) ↩

-

Brown, A.V. (1904). List of Tamil proper names (title page). Kuala Lumpur: Government Printing Office. (Call no.: RRARE 929.4 BRO; Accession no.: B16331012F) ↩

-

The Civil Services of Ceylon, the Straits Settlements and Hong Kong were collectively referred to as the Eastern Cadetships. See Mills, L.A. (2012). Ceylon under British rule 1795–1932 (p. 90). Routledge. (Not available in NLB holdings). For details about Alfred Vanhouse Brown, see The Directory & Chronicle of China, Japan, Straits Settlements, Malaya, Borneo, Siam, the Philippines, Korea, Indo-China, Netherlands Indies, etc. (1906). (p. 1192). Cambridge: Harvard University. (Not available in NLB holdings); Wright, A., & Cartwright, H.A. (1908). Twentieth century impressions of British Malaya: Its history, people, commerce, industries, and resources (p. 328). London: Lloyd’s Greater Britain Publishing Company, Limited. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.5103 TWE) ↩

-

Britto, F. (1986, Fall). Personal names in Tamil society. Anthropological Linguistics, 28 (3), 349–365. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Vijaya, M., et al. (2007). A study on Telugu-speaking immigrants of Tamil Nadu, South India. International Journal of Human Genetics, 7 (4), 303–306. Retrieved from Pennsylvania State University’s CiteSeerX website. ↩

-

徐玉虎. (2005). 郑和下西洋航海图考. In《郑和下西洋研究文选 (1905–2005)》(p. 530). Beijing: China Ocean Press. (Call no.: Chinese R q951.06092 ZHX); 巩珍 & 向达. (2000).《西洋番国志》. Beijing: Zhonghua Shu Ju. (Call no.: Chinese RSEA 959 GZ); 马欢 & 万明. (2005).《明钞本瀛涯胜览校注》. Beijing: China Ocean Press (Not available in NLB holdings); Ma, H. (1997). Ying Yai Sheng Lan: ‘The overall survey of the ocean’s shores’ [1433]. (Translated from the Chinese text edited by Feng Chʻeng-Chün with introduction, notes and appendices by J.V.G. Mills). Bangkok, Thailand: White Lotus Press. (Call no.: R 915.04 MA) ↩

-

Translated by J.V.G. Mills as Records of Military Preparations. ↩

-

Phillips, G. (1885–1886). The seaports of India and Ceylon described by Chinese voyages of the fifteenth century. Journal of the North China Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 20, 209–226; and 21, 30–42. ↩

-

Pulau Sakijang Pelepah is also known as Lazarus Island. ↩

-

Pulau Tembakul is also known as Kusu Island. ↩

-

Pulau Satumu is where Raffles Lighthouse is located. ↩

-

Pedra Branca is where Horsburgh Lighthouse is located. ↩