Cartography and the Rise of Colonial Empires in Asia

Chia Jie Lin highlights interesting cartographic efforts from the National Library’s latest exhibition on Asian maps.

Between the 17th and 20th centuries, Eastern and Western colonial empires expanded across the globe, carving up new territories for control, administration and economic exploitation. In East Asia, Manchu armies swept southwards from the Mongolian-Manchurian steppes and past the Great Wall of China to conquer Ming Chinese territories.1

Meanwhile in Europe, the East India Companies – such as the Dutch, English and French – set sail for Asia in search of spices and other lucrative trade opportunities. These armed trading behemoths-turned-imperial states forcefully established colonies across South and Southeast Asia, causing the deaths of thousands of indigenous peoples.

Cartography anticipated and perpetuated the expansion of these empires. In the metropole (the homeland of a colonial empire) and the colonies, emperors, kings, and colonial administrators commissioned extensive land surveys and cartographic projects to establish their power and articulate their claims of legitimate rule over newly conquered territories.

The relationship between cartography and colonial empires is one of the many stories in the National Library’s latest exhibition, “Mapping the World: Perspectives from Asian Cartography”. From the Indian Ocean to the Pacific, Asian cartography contains rich histories and diverse traditions. It communicates religious views of the world, represents centres of political and theocratic power, and embodies knowledge exchanges between the East and West. Maps were instruments of power and government, borne out of the complex encounters between the “colonial and the colonised, the imperial center and the periphery, the modern and the indigenous”.2

Qing Imperial Expansion

The Qing dynasty (1644–1911) was one of the most successful colonial empires in the early modern period.3 The empire was founded by the Manchus, who claimed descent from the Jurchens of Northeastern China. In 1644, the Qing claimed the territory of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), forming a vast empire in the wake of the Ming’s dissolution.4 Between 1660 and 1760, the Qing doubled the extent of its territories by defeating and allying with neighbouring powers to encompass frontier zones, including Mongolia, Xinjiang and Manchuria.5

Early Qing rulers sponsored indigenous (Chinese) mapping practices at the court to record and communicate knowledge of Qing territories. In 1646, two years after the founding of the Qing dynasty, Prince Regent Dorgon (多尔衮, r. 1643–50) ordered an empire-wide cadastral survey. Although the survey was conducted to collect land use records and facilitate land-based tax reforms, it had other goals: to strengthen the court’s reach and control over Qing territories and populations.6 Qing rulers sought to legitimise foreign Manchu rule over Chinese civilisation through such strategic mapping projects.

Dorgon’s empire-wide surveys were succeeded by Emperor Kangxi (康熙, r. 1662–1722) who, in 1684, commissioned “a systematic inspection… in each administrative division of the province [of Guangdong] to gain more accurate information on the names and locations of mountains and streams, the natural and artificial boundaries, the historic and scenic places and the distances between them”.7 As an alternative to Chinese mapmaking, Kangxi sponsored the development of European scientific surveys and cartographic techniques, with the goal of creating accurate to-scale maps for more effective administration of his domains.8

Between 1708 and 1715, Kangxi employed European Jesuit missionaries to conduct detailed surveys of his empire. The resulting maps, completed in 1718, were known as the Imperially Commissioned Maps of All Surveyed (皇舆全览图; huangyu quanlan tu), or the Kangxi Atlas. A year later, French Jesuit historian Jean-Baptiste Du Halde presented the Kangxi Atlas to Louis XV of France (r. 1715–74).9

Qing cartographic projects from the late 17th to 18th centuries were contemporaneous with national surveys and mapping activities sponsored by similarly ambitious monarchs in early modern Europe. Louis XIV (r. 1638–15), for example, sent French Jesuits to Kangxi’s court for knowledge exchange, and supported mapping projects in French colonies in the New World and back home. In Russia, Peter the Great (r. 1682–1725) commissioned the mapping of his domains.10 From Asia to Europe, imperial expansion was realised and articulated through extensive surveys and mapping of territories.

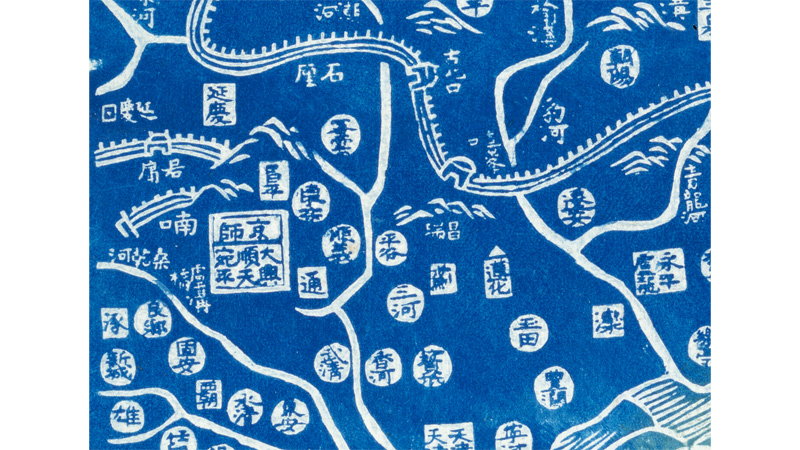

While maps articulated the administrative intricacies and changing boundaries of an expanding multicultural Manchurian empire, they also served as ideological tools to justify Qing expansionist policies. One example is the Complete Geographical Map of the Everlasting Unified Qing Empire (大清万年一统地理全图; Daqing wannian yitong dili quantu).

The map is a reprint of the All-Under-Heaven Complete Map of the Everlasting Unified Qing Empire (大清万年一统天下全图; Daqing wannian yitong tianxia quantu), first produced and presented by cartographer Huang Qianren (黄千人, 1694–1771) to Emperor Qianlong (乾隆, r. 1736–96) in 1767. It depicts administrative changes in the wake of military campaigns and treaty negotiations with frontier territories.11 The map shows the extent of the Qing realms, including internal frontiers, and features neighbouring states such as Korea and Annam (central Vietnam). It situates China as the Middle Kingdom (中国; zhongguo) at the centre of the world, with Europe and the Near East on the far periphery (depicted at the topmost left of the map). Cartographic symbols of varying shapes denote the different administrative divisions and units.

The preface, located at the bottom right, notes that the map was produced to communicate the new shape and scope of the empire (天下之广可以全览焉; “the vastness of the empire can be seen”). Furthermore, the map prominently features the newly conquered frontier regions of Mongolia, Tibet and Chinese Turkestan. In his book, Cartographic Traditions in East Asian Maps, Richard A. Pegg, Director of the MacLean Collection in Illinois, USA, notes that this court-produced map “confirms the Qing notion of the world”, particularly of Qianlong’s worldview at the peak of his reign.12

Historian Laura Hostetler notes that at an impressive 1.3 by 2.35 m, the map served an “imperial purpose – to awe those who viewed it with the grandeur of the Qing”.13 Its title, containing the words “unification” (一统; yitong) and “everlasting” (万年; wannian), symbolised an empire whose influence extended outwards – from the emperor in Beijing to its ever-expanding margins of frontiers, vassal states and overseas (海外; haiwai) territories.

After Qianlong’s passing in 1799, his heir Emperor Jiaqing (嘉庆, r. 1796–1821) commissioned reprints of the Complete Geographical Map of the Everlasting Unified Qing Empire in 1800, likely to celebrate the empire unified by his father. The map went through at least eight reprints during the 19th century, likely due to relaxed restrictions on the dissemination of geographical knowledge during the reigns of Emperor Jiaqing and Emperor Daoguang (道光; r. 1821–51). Many extant copies later found their way to Japan and were mounted onto Japanese folding screens and sliding doors. One copy, belonging to the Yokohama City University Library and Information Center and on display at the “Mapping the World” exhibition, comprises a set of eight hanging scrolls that come together to form the full map.

Joseon Korea

This imagined Qing universality was not reflected in the maps from Joseon Korea (1392–1910), its neighbour and vassal. Instead, during the late Joseon period from the 18th to 20th centuries (largely contemporaneous with Qing rule of China), Korean cartographers turned inwards, depicting in most cases only Korean territories. The Joseon state produced maps (chido, “land picture”) of all scales. These included detailed renderings for national administration purposes to pictorial maps of cities like the capital Hanseong (in present-day Seoul).

In the early Joseon period (1392–c. 1506), Korean cartography was characterised by an interest to justify and legitimise the new Joseon order, and to map territories for surveillance and control. In 1424, Sejong the Great (r. 1418–50) commissioned a survey of the Joseon nation-state, with questionnaires sent to the governors and magistrates of 334 districts seeking information on “boundaries, population sizes, administrative history, distances to neighbouring district centres, and data on human and physical geography of local areas”.14 By 1434, Sejong was seeking “full and detailed maps” from local administrators to strengthen centralised geographical information and, by extension, central political power.15

Early Joseon maps feature Korea in a Sinocentric world. They reflect the view of Korea’s ruling elite that their country was a rising power next to Ming China, the centre of civilisation at the time, while Japan was a rival state. The 1402 Map of Integrated Lands and Regions of Historical Countries and Capitals (of China) (Honil Gangni Yeokdae Gukdo Ji Do), or the Gangnido world map for short, shows Ming China – with its Great Wall – at the centre of the world, and an enlarged Korea situated next to it.16 The rest of the world frames the periphery of the map.17

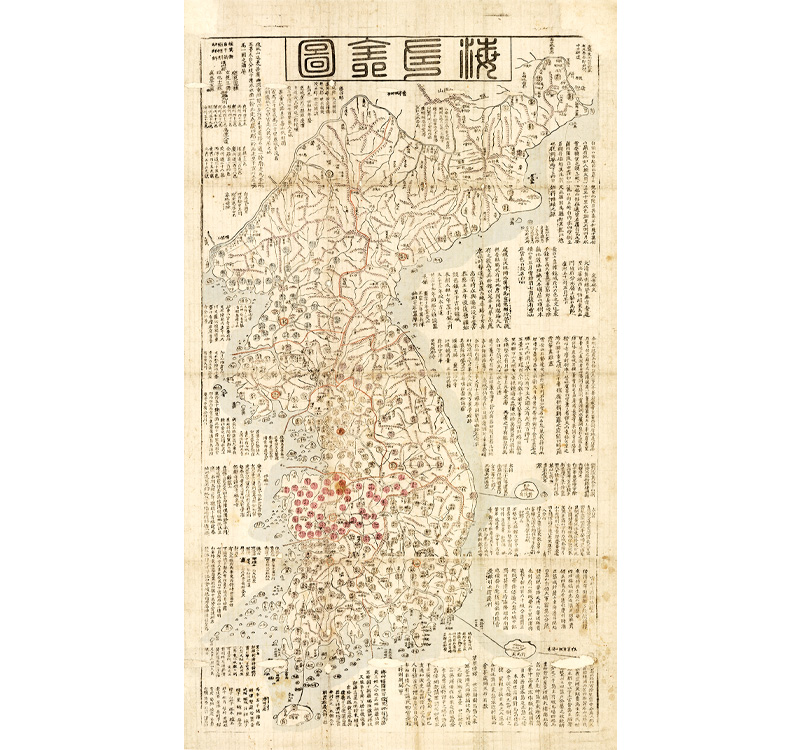

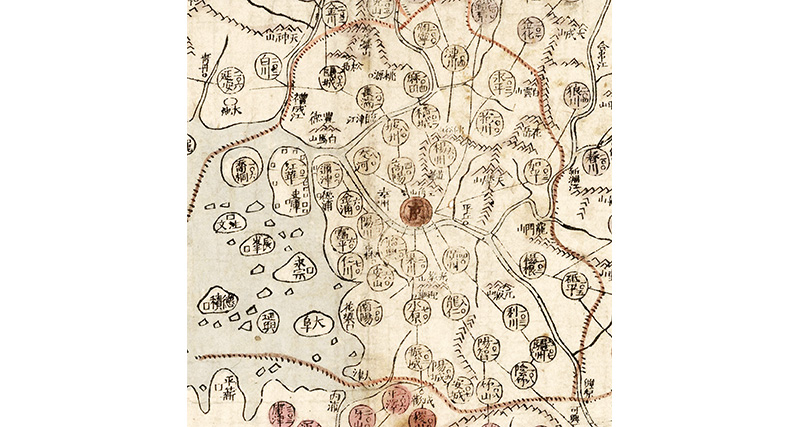

Conversely, late Joseon maps like the Haejwa Jeondo (海左全图; Map of Korea) depart from early Joseon cartography, and with good reason. Major foreign incursions marked the transition from the middle to late Joseon period in the 16th and 17th centuries, scarring the nation for centuries to come.

The Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–98), or Imjin War, devastated the peninsula. By 9 June 1592, less than three weeks after the Japanese landing in Busan on 23 May, the capital Hanseong had fallen. Over the span of seven years, the incursions caused an estimated two million in casualties and abducted civilian figures, amounting to 20 percent of the Joseon population.18 Ninety percent of the population were also rendered homeless, while Japanese soldiers collected 38,000 ears of defeated Korean troops to bury in the “ear mounds” of Osaka as spoils of war.19 Korean scholar O Huimun described “roads lined with corpses, the destruction of farmland, mass rapes, suicides of women who sought to escape capture, and reports of cannibalism in the starved population”.20

Admiral Yi Sun-shin (1545–98), often celebrated as Korea’s greatest war hero, raised an armada of large armoured “turtle ships” (Geobukseon warships) and naval forces, fighting against the Japanese until his death in the war’s final campaign.21

Decades later, Manchu forces invaded the Korean peninsula, angered by the latter’s support of the weakening Ming dynasty. The Manchu first struck in 1627 to threaten King Injo (r. 1623–49) into severing diplomatic ties with the Ming, and again in 1636 to punish the Koreans for breaking their 1627 oath of allegiance – previously made under duress – to the Qing.22

These invasions cast a long shadow over the Korean psyche. In their aftermath, Korea pursued a policy of seclusion that restricted relations with Japan, China and Europe until the mid-19th century. Korean cartographic interest turned from delineating the boundaries of national territory to asserting a sense of self-sovereignty as well as rejecting both Japanese and Chinese colonial ambitions over Korea. Joseon mapmaking “underwent groundbreaking developments, spurred on by an increased demand as the population was attempting to come to terms with the harmful effects of war,” writes Associate Curator Baik Seungmi of the National Museum of Korea.23

In the mid-18th century, Korean cartographer Jeong Sanggi (1678–1752) produced the Dongkuk jido (Map of Korea), hailed as the first map to “truly describe the Korean territory”.24 The Dongkuk jido was widely copied and disseminated by government officials and civilians, and later became the basis of block-printed national maps like the Haejwa Jeondo.25

The French Conquest of Indochina

From the 17th to 20th centuries, maps facilitated the expansion of European colonial empires across the world. By the 19th century, while the Netherlands had colonised the Dutch East Indies, and the British had controlled parts of Malaya and Burma (Myanmar), France had little colonial presence in Asia. Also of concern were their waning political dominance and prestige in Europe, as well as their trade competitor England’s easy access to the lucrative Chinese trade, enabled by the latter’s victory in the First Opium War (1839–41).26

China’s loss to Britain in the First Opium War marked the start of the Qing empire’s decline, with the latter forced to acquiesce to trade with the British via a series of unequal treaties.27 The British subsequently dominated China’s eastern coast, including an “open door policy” in Canton (Guangzhou) and along the Yangzi River.28

“The political control of this expedition,” the Special Commission for Cochinchina (Commission de la Cochinchina) noted in 1857, “arises from the force of circumstances propelling the Western nations toward the Far East. Are we to be the only ones who possess nothing in this area, while the English, the Dutch, the Spanish, and even the Russians establish themselves there?”29

To bypass the treaty ports of China’s coastal provinces, the French needed another trade route, this time through the Chinese mainland. In order to achieve this, France set its sights on colonising Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos. It sought to develop a “river policy” based on “exclusive, therefore colonial” control of the mouths of the Mekong and Red Rivers”.30 The rivers flowing through the territories of Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos enabled trade and travel, and supplied the people with water for daily consumption. The goal of the French was to “make Saigon a French Singapore”, according to the Marseille Chamber of Commerce in 1865.31

Maps and plans played a pivotal role in the French invasion of Vietnam. As French forces swept across northern Vietnam, they amassed local plans of fortresses, cities and frontier zones to gather knowledge of local terrains and peoples.

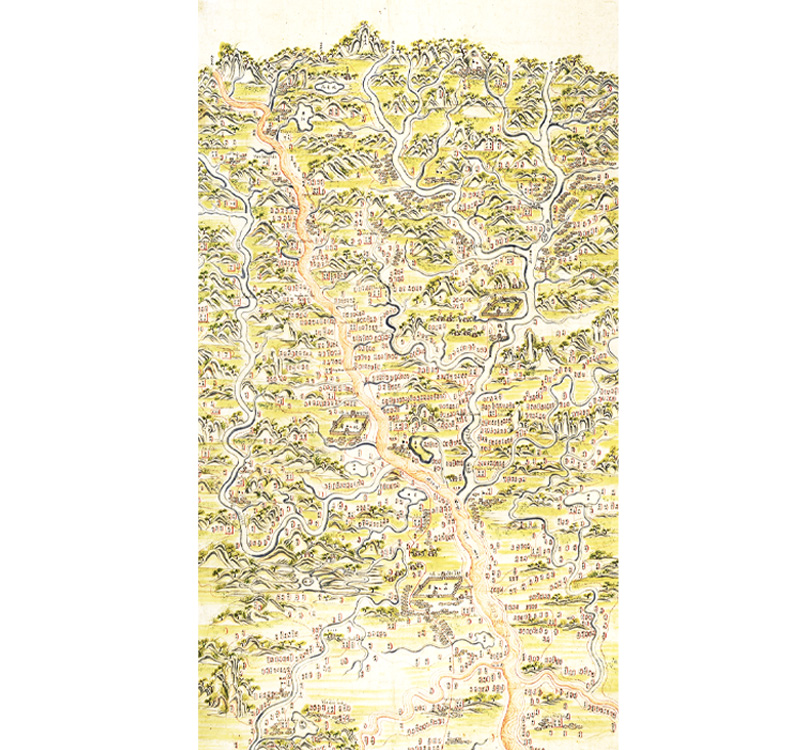

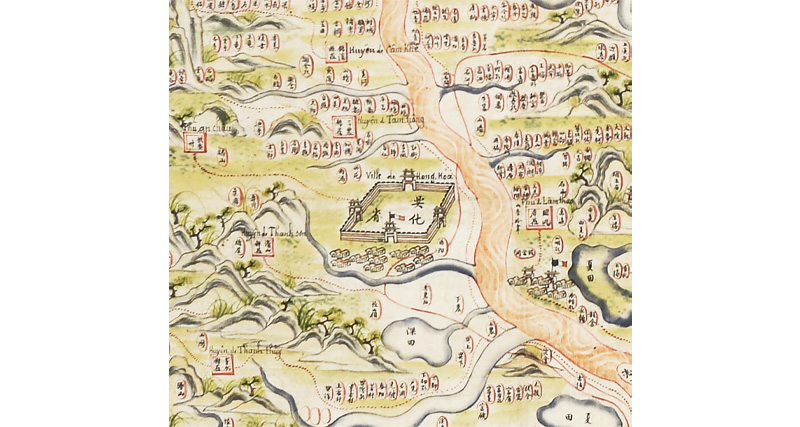

The Map of Northwest Tonkin, belonging to a French private collection, is one of the many maps collected during the 1880s. As early as the 1860s, the French had begun to covet Tonkin in northern Vietnam – which was then a vassal of China – as well as its capital and major port city Hanoi, and the Red River for their strategic trading access to China and the southern Vietnamese provinces. In 1883, French statesman Jules Ferry (1832–93) ordered an all-out invasion of Tonkin, leading to the Sino-French War (1883–85). While Qing Chinese forces retaliated to reclaim their tributary state, the French eventually won and affirmed its control of the protectorates of Tonkin and Annam (central Vietnam).

The presence of Latin romanised characters Quốc ngữ (“national language script”) alongside the Sino-Vietnamese Chữ Nôm (“southern characters”) script on the map likely facilitated its use by the French. Shown on the map are French flags marking the progression of French troops across northern Vietnam, making this Tonkin map a rare example of a Vietnamese map influenced by French colonisation.

The French conquest of Indochina spanned the late 19th century. In 1887, French Indochina – the collective Orientalist term for the French colonial territories of Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos – was born.32 The conquest also succeeded in destroying the region’s tributary relationships to the Beijing court. This marked the end of the pre-modern “world system” of Asia, one where Qing China held sway over tributary states at its southern periphery, such as the Vietnamese and Khmer kingdoms, as well as Lao and Tai principalities.

Indochina Mapped

During the period of European colonial expansion, explorers and imperial cartographers were interested in collecting and producing maps that “focused on ways of communication, rivers and roads that were perceived as Indochina’s neuralgic network” for reconnaissance purposes.33

Maps took on new roles after the establishment of French Indochina (1887–1954). Colonial maps, produced in situ by European and indigenous mapmakers, provided knowledge that allowed European administrators to govern their new colonial possessions more effectively, engendering a “progressively more invasive and direct administration over territory”.34 For one, the mapping of forests and their resources allowed colonial authorities to impose greater control on the use of natural resources by indigenous populations.35

Cartographic documents were also pivotal in defining and demarcating imagined national boundaries, allowing colonisers to lay claim to territories. From 1884 to 1895, the French explorer and diplomat Auguste Pavie (1847–1925), dubbed “the grand doyen of Indochinese mapping”, led several missions, known as “Missions Pavie”, to explore Indochina and the surrounding regions, including Siam. Pavie surveyed 676,000 sq km of land (over 900 times the size of Singapore) around the Vietnam-Laos boundary and the Laotian-Siamese border, creating “fixed” national borders that had not existed previously.36 In turn, his work paved the way for the French to identify Cambodian and Laotian territories upon which they could impose their authority.

Pavie’s cartographic exploits were so transformative that the lack of them apparently weakened colonial control, as historian Olivier Schouteden wrote:

“Indeed, on May 24 1897, the Commandant Superior of Higher Laos blamed his impossibility to enforce border control requested by the Government General of Indochina on Pavie himself, arguing that ‘Mister Pavie had recommended to not carry out a topographic study of the frontiers’, and as a consequence, the maps produced by the mission, which were then the only ones available, did not ‘indicate [such] limits’.”37

The unspecified colonial administrator was likely Louis Paul Luce (1856–1931), who served as Interim Commandant-Superior of Haut-Laos from May 1897 to October 1898. In his argument, the Commandant-Superior critiqued the failure of Pavie’s maps to indicate the “limits” of Indochina at its borderlands. The assumption seemed to be that had Pavie done so, the maps would have been able to effectively resolve Siam and Indochina’s competing territorial claims.

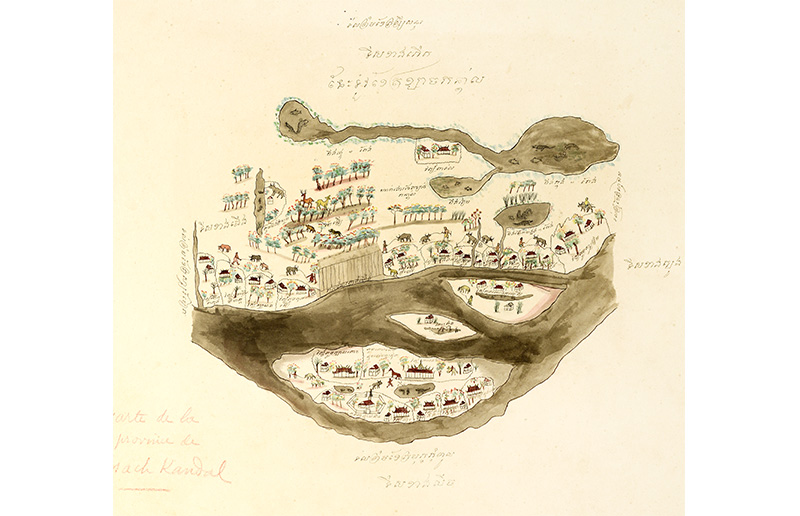

Meanwhile, maps produced by indigenous mapmakers provided an in-depth look at the lives of local populations. The Map of Khsach-Kandal was produced by Cambodian elites at the behest of French authorities, and on paper supplied by the French military. It sensitively depicts the daily life of rural civilians in Khsach Kandal, near the capital Phnom Penh.

At close glance, we see civilians leading their cows around the villages, while Buddhist temples, pagodas and village dwellings nestle within the natural landscape featuring trees and wild animals. Marine life such as fishes and crocodiles can be seen in the water bodies (in dark grey), denoted by the term “pond” in Khmer. The larger of the two “ponds” at the bottom most likely depicts the nearby Mekong River that flows past the towns of Svay Romiet, Khsach Kandal and Lvea Aem, with all three depicted on the map.

This commissioned map is part of a collection of maps from the library of the École française d’Extrême-Orient (EFEO; French School of Asian Studies). Headquartered in Hanoi, the EFEO was founded as the Indochina Archaeological Mission in 1898 before taking on its current name in 1900.

According to geographer Charles Robequain (1897–1963), who studied at the EFEO from 1924 to 1929, the EFEO sought to obtain “knowledge of native society, of the peasants’ mental processes” via field work-based research to further colonial control.38 Until the end of French colonial rule in Indochina in 1954, cartography remained pivotal for administrative purposes, providing information on indigenous landscapes, population structures and distribution, as well as the lives of local populations.

Cartographic Legacies

Modern cartographic conceptions have often reduced maps to accurate representations of physical space and geographical realities. This narrow definition, however, could not be further from the truth for historical maps. Such maps can be forms of “world-making” as symbolic and graphical representations that embody and reflect complex understandings of the world, their makers’ beliefs and cultural realities, among others. Under the auspices of colonialism, maps were also artefacts of “world-taking” that have modern-day ramifications.39 The cartographic legacies of former colonial empires in Asia remain relevant and continue to shape contemporary geographical imaginaries alongside our understanding of their histories.

Today, the contours of the People’s Republic of China correspond largely to Qing-era maps of the 17th and 18th centuries.40 Closer to home, the formation of several Southeast Asian nations were similarly borne out of colonial-era cartography, the defining of national borders and the consolidation of previously semi-autonomous states. Even the creation of the modern Thai nation (previously Siam), which was spared European colonisation, was influenced by scientific mapping practices that displaced indigenous conceptions of space.41

The legacies of colonialism are still evident today. Asian maps, produced in-situ by indigenous cartographers, are among countless artefacts located far away from their homelands and displaced from their original systems of knowledge. For example, under colonial expansion and subsequent French rule in Indochina, many Vietnamese maps made their way into the collections of French and other European institutions.42

Such histories and discourses remain relevant to Singapore – our intellectual legacy as a former colony is intertwined with those of other Asian nations. The “Mapping the World” exhibition grapples with the diverse and complex histories of maps and mapmaking in Asia. It brings to the fore an Asian-centric history of cartography and, in doing so, introduces its fascinating yet lesser-known stories for audiences in Singapore.

The author thanks history student Jacqueline Yu for her research assistance.

Level 10 Gallery, National Library Building

11 December 2021 – 8 May 2022

Discover the maps mentioned in this essay and more at the National Library’s latest exhibition produced in partnership with the Embassy of France in Singapore, in association with the vOilah! France Singapore Festival 2021 and with the support of Temasek and Tikehau Capital.

The exhibition features over 60 cartographic treasures from institutions in France, the United States, Japan and Singapore.

The exhibition is open from 10 am to 9 pm daily, except on public holidays. Admission is free.

As an accompaniment to the exhibition, a book with the same title has been published. It is written by curators Pierre Singavélou and Fabrice Argounès, with inputs from the National Library’s curatorial team. Mapping the World: Perspectives from Asian Cartography is available for download on BookSG , for reference at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and for loan at selected public libraries (Call nos. RSING 526.095 SIN and SING 526.095 SIN)

Chia Jie Lin is an Assistant Curator with Programmes & Exhibitions at the National Library, Singapore. She is part of the France-Singapore curatorial team of the “Mapping the World: Perspectives from Asian Cartography” exhibition.

Chia Jie Lin is an Assistant Curator with Programmes & Exhibitions at the National Library, Singapore. She is part of the France-Singapore curatorial team of the “Mapping the World: Perspectives from Asian Cartography” exhibition.

NOTES

-

For more on the discussion of Qing China as a colonial empire, see Peter C. Perdue, “China and Other Colonial Empires,” The Journal of American-East Asian Relations 16, no. 1/2 (2009): 85–103. See also Julia C. Schneider, “A Non-Western Colonial Power? The Qing Empire in Postcolonial Discourse,” Journal of Asian History 54, no. 2 (2020): 311–42. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

John Rennie Short, “Introduction: The Globalisation of Space” in Korea: A Cartographic History (University of Chicago Press, 2012), x. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. R 912.519 SHO) ↩

-

I follow Sanjay Subrahmanyam’s description of the early modern period as being from the 15th to the middle of the 18th centuries. Sanjay Subrahmanyam, “Hearing Voices: Vignettes of Early Modernity in South Asia, 1400–1750.” Daedalus 127, no. 3 (1998): 75–104. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Laura Hostetler, “Qing Connections to the Early Modern World: Ethnography and Cartography in Eighteenth-century China,” Modern Asian Studies 34, no. 3 (2000): 630. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Laura Hostetler, “Contending Cartographic Claims? The Qing Empire in Manchu, Chinese and European Maps” in The Imperial Map: Cartography and the Mastery of Empire, vol. 15, ed. James R. Akerman (University of Chicago Press, 2009), 93–132. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Stephen H. Whiteman, Where Dragon Veins Meet: The Kangxi Emperor and His Estate at Rehe (University of Washington Press, 2019), 65. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Arthur Hummel, “Atlases of Kwangtung Province,” in Annual Report of the Librarian of Congress for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1938 (Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1939), 229–30, HathiTrust, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015019350415&view=1up&seq=9&skin=2021. ↩

-

Laura Hostetler, Qing Colonial Enterprise: Ethnography and Cartography in Early Modern China (University of Chicago Press, 2001), 70–71. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. R 951.03 HOS) ↩

-

Mario Cams, “The China Maps of Jean-Baptiste Bourguignon d’Anville: Origins and Supporting Networks,” Imago Mundi 66, no. 1 (2014): 51–69, Taylor & Francis Online, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03085694.2014.845949. ↩

-

Hostetler, Qing Colonial Enterprise, 4, 72. ↩

-

Richard A. Pegg, Cartographic Traditions in East Asian Maps (Honolulu: The MacLean Collection and University of Hawai’i Press, 2014), 24–25. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Pegg, Cartographic Traditions in East Asian Maps, 18–25. ↩

-

Hostetler, “Contending Cartographic Claims?,” 123. ↩

-

Short, Korea: A Cartographic History, 18. ↩

-

Short, Korea: A Cartographic History, 18. ↩

-

The Gangnido world map is the oldest extant national map of Korea and one of the oldest world maps from East Asia. ↩

-

Short, Korea: A Cartographic History, 4. ↩

-

Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, “About,” Aftermath of the East Asian War of 1592–1598, accessed 1 November 2021, https://aftermath.uab.cat/about/. ↩

-

Marc Jason Gilbert, “Admiral Yi Sun-Shin, the Turtle Ships, and Modern Asian History,” Asia in World History: 1450–1770 12, no. 1 (Spring 2007): 29–35, Association for Asian Studies, https://www.asianstudies.org/publications/eaa/archives/admiral-yi-sun-shin-the-turtle-ships-and-modern-asian-history/. ↩

-

John Woodford, “Imjin War Diaries are Memorial of Invasions for Koreans,” The University Record, 22 February 1999, University of Michigan, https://www.ur.umich.edu/9899/Feb22_99/imjin.htm. ↩

-

Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica, “Yi Sun-shin,” Encyclopedia Britannica, 24 April 2021, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Yi-Sun-shin. ↩

-

John Kallander, “Introduction” in The Diary of 1636: The Second Manchu Invasion of Korea (University of Chicago Press, 2020), xii. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Baik Seungmi, “500 Years of the Joseon Dynasty Maps,” National Museum of Korea: Quarterly Magazine 44 (Summer 2018), issuu, accessed 1 November 2021, https://issuu.com/museumofkorea/docs/nmk_v44/s/12345626. ↩

-

“Territory and Ancient Maps,” National Atlas of Korea, accessed 1 November 2021, http://nationalatlas.ngii.go.kr/pages/page_554.php. ↩

-

“Territory and Ancient Maps.” ↩

-

Pierre Brocheux and Daniel Hémery, “Introduction” in Indochina: An Ambiguous Colonization, 1858–1954 (University of California Press, 2009), 14. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSEA 959.703 BRO) ↩

-

Xavier Lacroix, “Unequal Treaties with China”, Encyclopédie d’histoire numérique de l’Europe , 22 June 2020, https://ehne.fr/en/node/12502. ↩

-

Brocheux and Hémery, Indochina: An Ambiguous Colonization, 1858–1954, 9. ↩

-

Quoted by Georges Taboulet, La Geste Francaise en Indochine, vol. 1 (Paris: Adrien-Maisonneuve, 1955–56), 242. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Brocheux and Hemery, Indochina: An Ambiguous Colonization, 1858–1954, 9. ↩

-

Marseille Chamber of Commerce, letter to the ministre de la marine et des colonies, May 9, 1865, Centre des archives d’outre-mer, Aix-en-Provence [CAOM], AFJ, d. 11. ↩

-

Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica, “Indochina,” Encyclopedia Britannica, 28 January 2020, https://www.britannica.com/place/Indochina. ↩

-

J.B. Harley, “Maps, Knowledge, and Power,” in The New Nature of Maps: Essays in the History of Cartography, ed. Paul Laxton (Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001), 57. (Not available in NLB holdings); Olivier Schouteden, “Impossible Indochina: Obstacles, Problems and Failures of French Exploration in Southeast Asia, 1862–1914” (PhD diss., Northeastern University, 2018), 167, accessed 29 November 2021, https://repository.library.northeastern.edu/files/neu:m044c558x. ↩

-

L.F. Braun, “Colonial and Imperial Cartography,” in The History of Cartography, Volume 6: Cartography in the Twentieth Century, Part 1, ed. Mark Monmonier (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015), 251–52; accessed 29 November 2021, https://press.uchicago.edu/books/HOC/HOC_V6/Volume6.html. ↩

-

These included “the classification of species, the delimitation of forest reserves, and the creation of forest institutions such as botanical gardens and forest agencies.” Pamela McElwee and Mark Cleary, cited in Thuy Linh Nguyen, “Coal Mining, Forest Management, and Deforestation in French Colonial Vietnam,” Environmental History 26, no. 2 (April 2021): 256, Oxford Academic, https://academic.oup.com/envhis/article-abstract/26/2/255/6207546. ↩

-

Milton E. Osborne, The Mekong: Turbulent Past, Uncertain Future (New York: Grove Press, 2000), 118–21. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSEA 959.7 OSB) ↩

-

Schouteden, “Impossible Indochina,” 329. ↩

-

Gavin Bowd and Dan Clayton, “Fieldwork and Tropicality in French Indochina: Reflections on Pierre Gourou’s Les Paysans Du Delta Tonkinois, 1936,” Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 24, no. 2 (2003): 154, ResearchGate, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/230280254_Fieldwork_and_Tropicality_in_French_Indochina_Reflections_on_Pierre_Gourou’s_Les_Paysans_Du_Delta_Tonkinois_1936. ↩

-

I borrow Reuben Rose-Redwood’s description of maps as forms of “world-making” and “world-taking”. See Reuben Rose-Redwood, “Beyond the Colonial Cartographic Frame: The Imperative to Decolonize the Map,” University of Toronto Press, 11 November 2020, https://blog.utpjournals.com/2020/11/11/beyond-the-colonial-cartographic-frame-the-imperative-to-decolonize-the-map/. ↩

-

The modern borders correspond largely to Qing-era borders, save for Outer Mongolia which had declared independence from Qing rule in 1911. See Hostetler, “Qing Connections to the Early Modern World,” 623. ↩

-

Thongchai Winichakul, Siam Mapped: A History of the Geo-body of a Nation (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1994). (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSEA 911.593 THO) ↩

-

John K. Whitmore, “Cartography in Vietnam,” in The History of Cartography, Volume 2, Book 2: Cartography in the Traditional East and Southeast Asian Societies, ed. J.B. Harley and David Woodward (Illinois: University of Chicago Press, 1994), 506. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. R q526.09 HIS) ↩