Printed on Rubber Latex Paper

An innovation patented in 1920 produced paper that was more durable, had greater tensile strength and was resistant to folding, as Alex Teoh tells us.

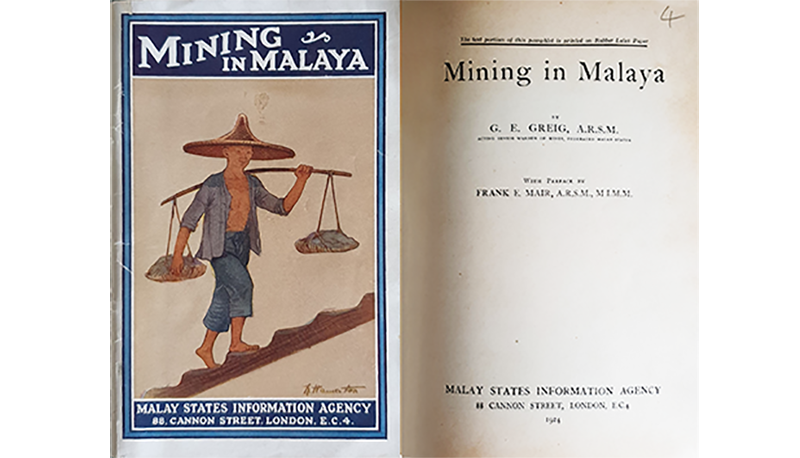

During the British Empire Exhibition held at Wembley Park, England, from 23 April to 1 November 1924, a number of handbooks were published and distributed that promoted the economy and produce of British Malaya. Published by the London-based Malay States Information Agency, these handbooks included titles such as British Malaya: Trade & Commerce; Rubber Planting in Malaya; Coconut Industry in Malaya; Big Game Shooting & Motoring in Malaya; and Mining in Malaya.1

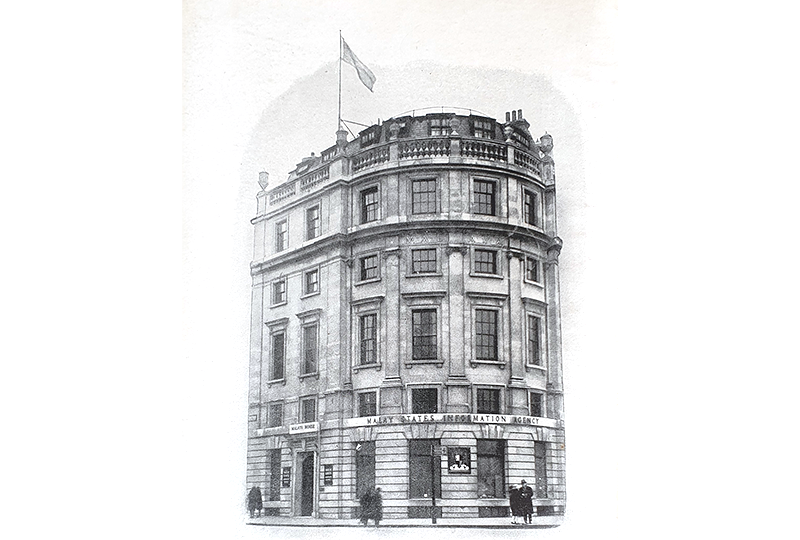

The agency was set up in 1910 as the Malay States Development Agency, which was renamed Malay States Information Agency the next year. Its mission was to provide information to prospective investors to boost land cultivation and trade in British Malaya. Through various public relations initiatives, advertisements and exhibitions, Malaya’s primary produce like rubber, coconut, pineapple and gambier and minerals such as tin were made known to the British Empire and the world. In 1928, the agency was renamed yet again as the Malayan Information Agency and occupied a building called Malaya House in London’s Trafalgar Square.

In addition to producing handbooks about topics related to Malaya, the agency also subtly aimed to show off Malayan products in other ways. On the title page of each handbook published by the agency for the British Empire Exhibition is the line: “The text portion of this pamphlet is printed on Rubber Latex Paper.” The printed pages appear off-white, slightly glossy and, after all these decades, still in good condition. The wove paper has a uniform surface, not ribbed or watermarked, and has a thickness of around 0.1 mm (similar to the 70gsm paper used today for photocopying).

What is Rubber Latex Paper?

Rubber was, of course, the chief agricultural product of the Malay Peninsula at the time.2 Commercially planted since 1895, British Malaya supplied more than half of the world’s rubber by the 1930s.3

Rubber latex paper was made by mixing liquid latex into paper pulp during paper-making. This process was developed by Professor Frederick Kaye of the Manchester College of Technology and patented in 1920.4 It was then commercially tested with free shipments of rubber latex to paper mills in England, Holland, Belgium and the United States.5

During the 1920s, the price of rubber slumped and rubber export restrictions were instituted to halt falling prices. As such, any new uses of rubber to increase demand would have been welcomed by Malayan planters and rubber investors.

The use of rubber latex in paper-making garnered considerable news coverage in 1922 and 1923. In April 1922, the Straits Times noted that rubber latex appeared to “improve the texture [of paper] and makes the paper more uniform when viewed by transmitted light. The feel of the paper, especially with paper containing large amounts of rubber, is much improved and becomes pleasant to the touch”. It added that “paper containing rubber latex is more water-repellent than the same paper without rubber, and a suitable treatment of the fibres in paper-making with rubber latex will give a water-proof paper”. In addition, the “electrical resistance and dielectric properties of paper may be improved by the addition of rubber latex”. The paper became more absorbent with better hydration, while the production cost was also reduced considerably.6

In addition, rubber latex paper also reportedly had increased “folding resistance” (a measure of the paper’s resistance to cracking along the crease when folded) and “bursting strength”. “[A]n untreated manila paper gave a folding resistance of 726, and a bursting strength of 41 lb. (per square inch calculated to a thickness of 1–10th millimetre), while the same paper, treated, increased its folding resistance to 24,000, and its bursting strength to 60 lb. An ordinary printing paper, untreated, had the low folding resistance of 2; treated, this rose to no less than 250, or 125-fold; the increase in bursting strength was from 7 lb. to 20 lb.”7

Besides paper-making, there were suggestions to use rubber latex for other things like making paper food containers that would be “stronger, tougher, and more damp-proof than at present”.8 The possibility of using rubber latex for currency notes was also raised.9 There was also a suggestion that Malaya start manufacturing paper as well.10

However, paper manufacturers were not entirely receptive to using rubber latex. Due to rubber export restrictions and shipment costs, variable prices and additional costs worried the paper mills. There were also concerns about the licencing cost of this technology, the effect of latex on the pulp mixing equipment and the lack of demand for rubber latex paper.

A Singapore Free Press report summarised the problem: “In the first place, excepting in rubber producing countries, there is no general demand for rubber latex paper, and consequently a strong case has to be made out for the inclusion of rubber latex in the raw ingredients, which go to form the finished paper material.” Paper manufacturers were also reluctant to “add more than 2 per cent of rubber latex to the total ingredients of the paper pulp, and in practice manufacturers have found that even this 2 per cent, instead of finding its way to the finished paper, merely tends to accumulate on the various exposed surfaces of the paper-making machinery causing the machinery to become ‘tacked up’ which results in the necessity at the end of the run in which the rubber latex has been used, for a complete cleaning up of the machinery”. Manufacturers claimed that the tackiness interfered with the running of the machinery, “resulting in a loss of time in cleaning up the machine after its use, and a consequent loss of money which in turn has to be added to the cost of the paper”.11

Commercial Latex Paper

There were some efforts to use rubber latex paper commercially. It was used for the printing of company reports of several major publicly listed companies and associations in Malaya, including Guthrie & Co., Fraser and Neave, Ltd., Robinson and Co., Singapore United Rubber and the Planters’ Association of Malaya.12 In 1923, London’s Investors’ Chronicle became the first newspaper to be printed on rubber latex paper.13

For the Malaya Pavilion at the British Empire Exhibition in 1924, the 2,000 copies of various pamphlets on different topics produced for sale used up two tons of paper, 3 percent of which was made of rubber latex.14

A company that manufactured latex paper was Messrs Lepard and Smiths, Limited, one of the oldest paper merchants in London. They produced envelopes, bank and bond papers aswell as cream laid writing papers, known as “Latex Papers”, at their warehouses in London. These were then shipped and stored in Singapore and elsewhere to meet demand.15

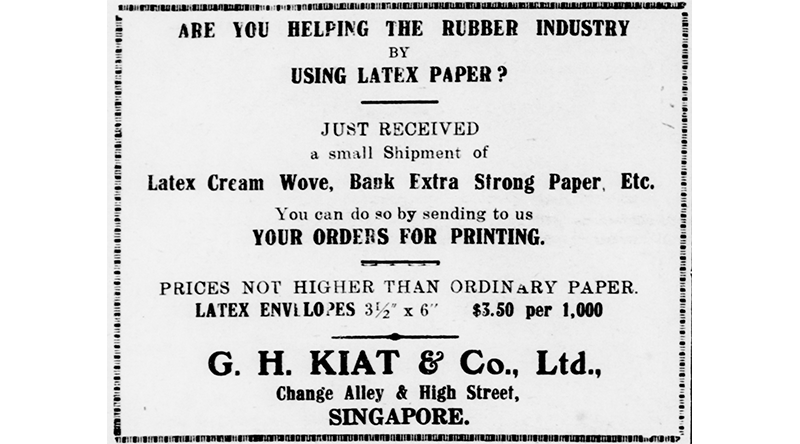

In Singapore and Malaya, latex paper was advertised and sold by major merchandisers like Fraser and Neave, Ltd.16, John Little & Co., Ltd.17 and G.H. Kiat & Co., Ltd.18

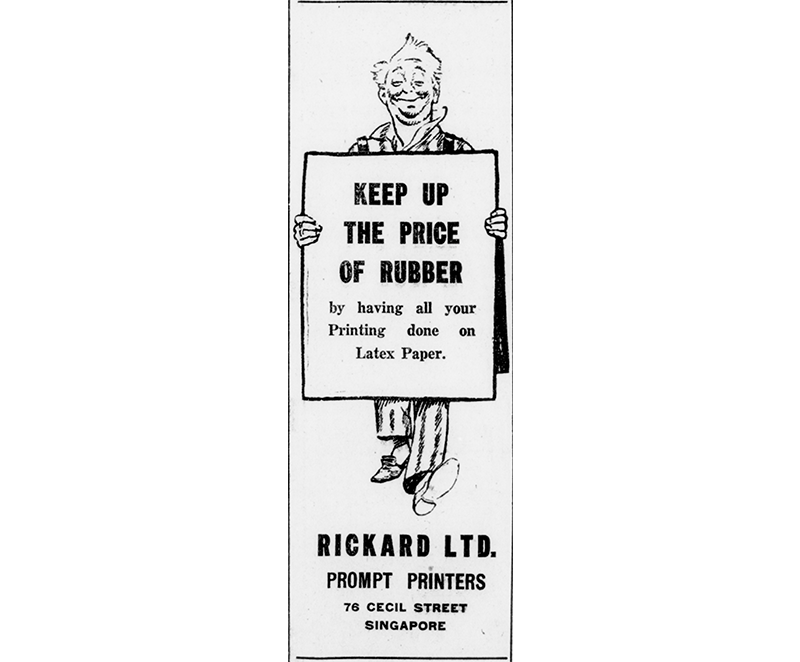

In 1925 and 1927, printing company Rickard on Cecil Street embarked on a targeted advertising campaign for its latex paper. The marketing slogan in the daily newspapers was “Keep Up the Price of Rubber by Having All Your Printing Done on Latex Paper” and “To Managers of Rubber Estates – Insist on Having All Your Printing – Letter Heads, Memos, Check Rolls, Etc. Etc. Done on Latex Paper”.19 The bookshop G.H. Kiat & Co. attempted to prod companies into using the paper by asking: “Are You Helping the Rubber Industry by Using Latex Paper?”20

In 1926, John Little & Co. offered a new series of Christmas greetings cards featuring “etchings of local beauty spots by Mrs G. Sinclair”, printed on a special grade of latex paper.21 Three years later, John Little launched its exclusive stationery brand of writing pads, note paper and envelopes called Rubtext Stationery. These used “distinctive high quality paper with semi-smooth finish” and were made in two finishes, antique and ripple, with each finish in four colours – white, sea blue, maize and mauve.22

However, after the 1930s, mentions of rubber latex paper dried up in the Malayan press. Although the term “rubber latex paper” may not be familiar to the younger generations today, we still have handbooks and publications that serve as reminders of this fascinating attempt to create a new market for a product that was very much a part of the history of Singapore and Malaya.

Alex Teoh is a paper and book conservator, providing collection care for rare manuscripts, collectible prints, antique maps and antiquarian books. He is interested in the local material culture of the written text in Southeast Asia.

Alex Teoh is a paper and book conservator, providing collection care for rare manuscripts, collectible prints, antique maps and antiquarian books. He is interested in the local material culture of the written text in Southeast Asia.NOTES

-

The National Library has some of these titles. See Malay States Information Service, British Malaya: Trade & Commerce (London: Malay States Information Agency, 1924). (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RDTYS 381.09595 BRI); Theodore Rathbone Hubback, John H.M. Robson and Howard Henry Banks, Big-game Shooting (London: Malay States Information Agency, 1924). (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RRARE 799.29595 HUB; Microfilm no. NL29281); Gordon Eastley Greig, Mining in Malaya (London: Malay States Information Agency, 1924). (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RCLOS 622.09595 GRE-[RFL]) ↩

-

Eric MacFadyen, Rubber Planting in Malaya (London: Malay States Information Agency, 1924). (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

The writer referenced the 1926 edition which is not available in NLB. The earliest version that NLB has is the 1935 edition. See Ralph Lionel German, Handbook to British Malaya (London: Malay States Information Agency, 1935). (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RRARE 959.503 HAN-[JSB]) ↩

-

“Rubber and Paper,” Straits Times, 24 July 1922, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Latex in Paper-making,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 5 October 1922, 13; “The Kaye Process,” Straits Times, 11 October 1922, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Rubber for Paper Making,” Straits Times, 22 April 1922, 2. (From NewspaperSG); “Latex in Paper-making”; “The Kaye Process.” ↩

-

“Latex Additions in Papermaking,” Malaya Tribune, 12 May 1922, 3; “Latex in Papermaking,” Straits Times, 18 May 1922, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Rubberised Paper,” Malaya Tribune, 26 October 1922, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Use of Latex in Paper-making,” Straits Times, 16 November 1922, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Rubber Latex in Paper,” Straits Times, 18 January 1923, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Latex Paper,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 25 June 1924, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Untitled,” Straits Times, 17 November 1922, 8; “Singapore United Rubber,” Straits Times, 27 December 1922, 11; “Untitled,” Straits Times, 13 June 1923, 8; “Company Reports: Fraser and Neave, Ltd.,” Malaya Tribune, 17 March 1923, 8; “Robinson and Co.,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 7 April 1923, 16. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“First Rubber Newspaper,” Malaya Tribune, 8 January 1923, 7; “Rubber Paper,” Straits Times, 8 January 1923, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Malayan Propaganda,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 1 May 1924, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Latex Paper,” Malaya Tribune, 13 January 1923, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Latex Paper in Singapore,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 24 March 1923, 10; “Page 1 Advertisements Column 1,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 24 March 1923, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Page 8 Advertisements Column 1,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 17 June 1929, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Page 6 Advertisements Column 1,” Malaya Tribune, 19 June 1923, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Page 2 Advertisements Column 2,” Straits Times, 9 November 1925, 2; “Page 2 Advertisements Column 2,” Straits Times, 7 November 1927, 2; “Page 2 Advertisements Column 2,” Straits Times, 2 December 1925, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Page 8 Advertisements Column 1,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 3 November 1926, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Page 8 Advertisements Column 1,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 17 June 1929, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩