The Early Days of Family Planning in Singapore

Singapore’s family planning programme did not start with the “Stop at Two” policy in 1972, but goes back even earlier to 1949.

By Andrea Kee

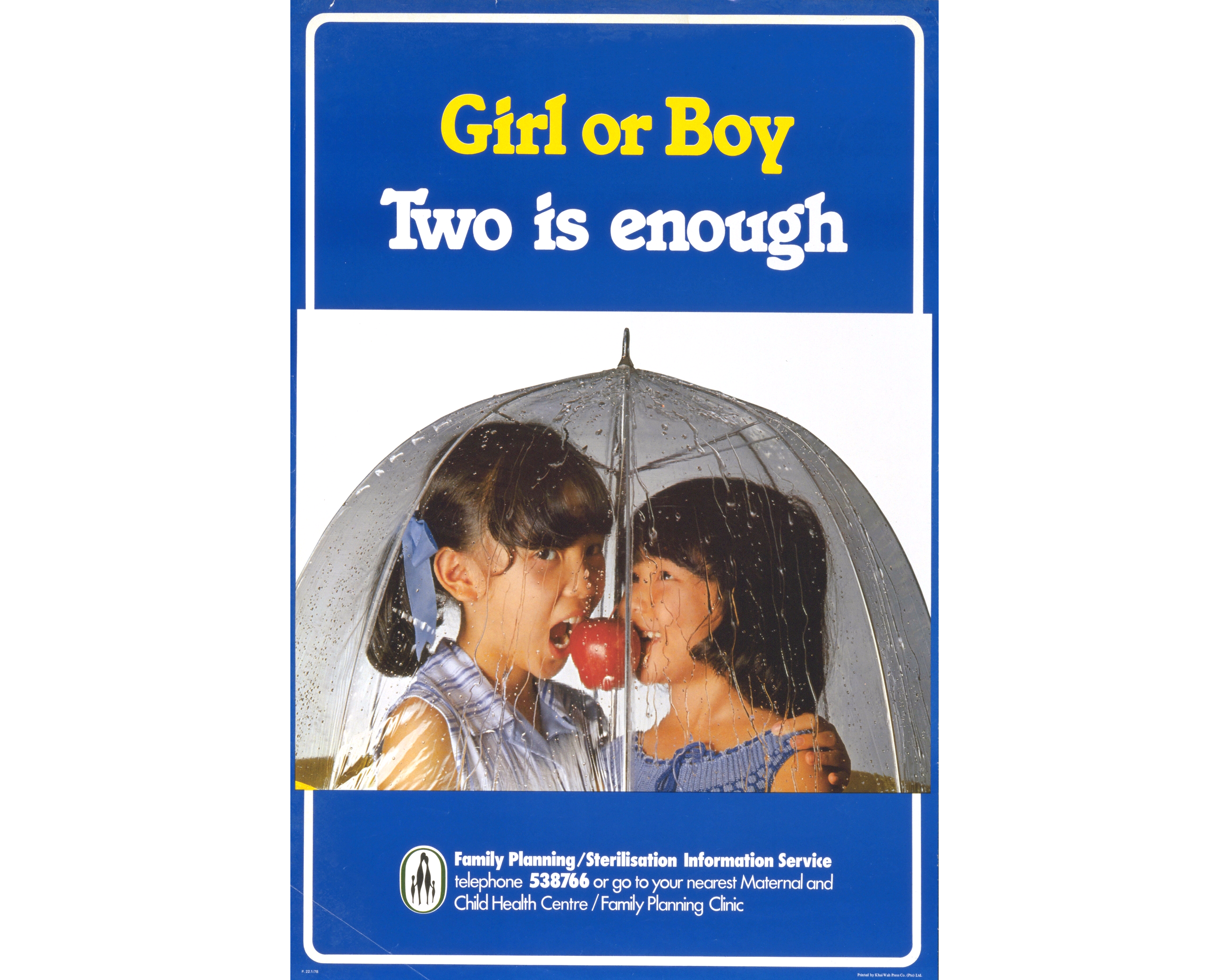

Mention “family planning” in Singapore and the poster of two girls sharing an apple under an umbrella with the slogan, “Girl or Boy, Two Is Enough”, invariably comes to mind. The “stop at two” campaign, which began in 1972, blanketed Singapore with the message on posters and bus panels, in magazines and in advertisements, and even on television and in cinemas.1

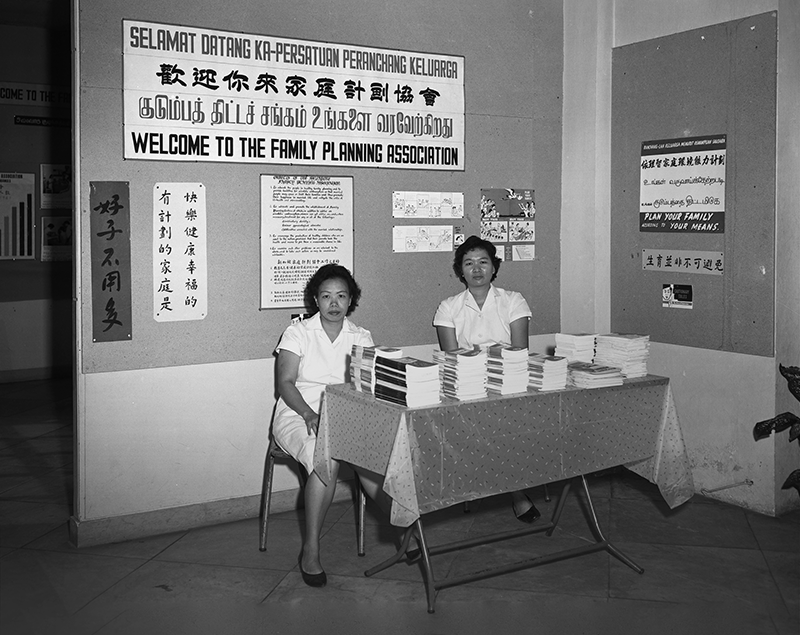

However, family planning in Singapore actually goes back even earlier than 1972. Organised attempts to reduce family sizes here date to the immediate postwar era when the Singapore Family Planning Association (SFPA) was set up in 1949.

The Work of Volunteers

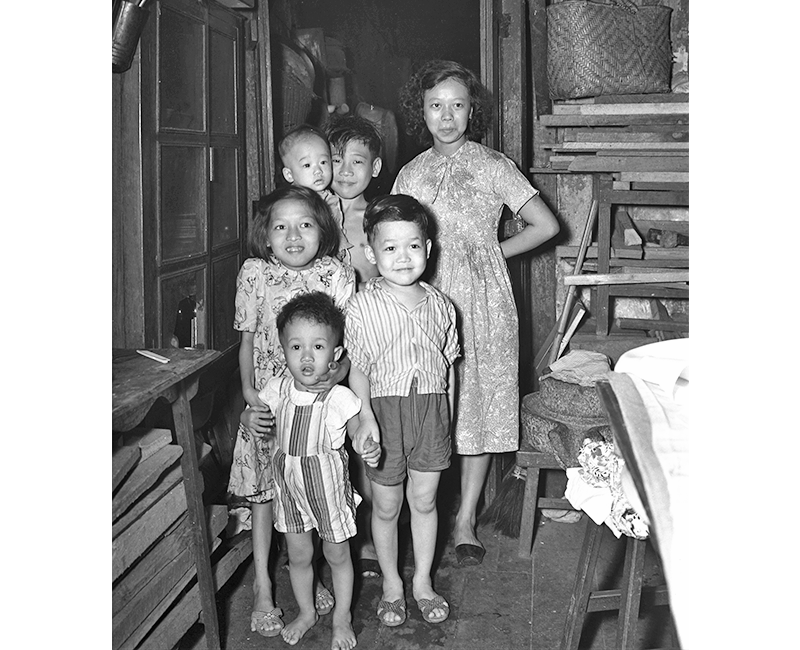

Postwar Singapore was plagued with hardship and poverty. The Japanese Occupation period resulted in a shortage of many things, but most urgent of these was food. To feed the hungry, the Social Welfare Department set up volunteer-run food centres to supply free meals. However, the volunteers soon realised that simply providing free food and education to those seeking help was not enough.

“We thought this is not the way how to tackle [the issue],” recalled Hena Sinha, a volunteer with the department, in an oral history interview. “Must teach them not to have so many children, how to space them. Not stop them. Have enough. That’s how it first started, from voluntary nursing, feeding the poor children, teaching them. Suddenly, we realised we must teach the parents not to have so many children,” she said.2

In July 1949, a group of volunteers, doctors and social workers came together to establish the SFPA, with the objective of providing contraceptive services and information to the masses so that women could plan their births and improve their own and their children’s welfare.3 The association set up family planning clinics where women could get contraception help and subsidised supplies, as well as seek minor gynaecological treatments.4

Sinha, who later became the association’s chairman, recalled that many poor women visited the clinics crying that they did not want any more children as they lacked money. In one case, a woman who had been pregnant 22 times “begged the doctors ‘to do something to stop it all’”, according to Goh Kok Kee, the president of the association. The woman already had 20 children and her husband was unemployed.5

Male attitudes were not helpful, as a 1950 Malaya Tribune article noted about a woman who had six children, two of whom had already been given away. “Her husband’s attitude was that he didn’t mind how many more children she had – they could always be given away, and she came begging that something could be done to prevent her having to have more children only to give them away.”6

Demand for the SFPA’s services was high and between 1949 and 1965, they grew from three clinics to 34. In those 16 years, almost 10,000 people sought and accepted family planning advice from the association. They could have possibly reached more women but being a non-profit private organisation, the association had limited resources and funds to keep up with demand.7 Nonetheless, the groundwork was laid for the next stage of family planning in Singapore.

Reaching Out to the Masses

By 1957, the SFPA struggled to cope with demand for its clinical services and appealed to the government for help. However, it was not until September 1965 when the White Paper on Family Planning was published that a national policy on family and population planning was instituted.8

The paper announced the launch of the first five-year family planning programme with the slogan, “Family Planning for All”. It also revealed the twin objectives of improving the health and welfare of mother and child, and accelerating fertility decline to benefit the socioeconomic development of Singapore.9

In 1968, Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew connected the issues of family planning, the growing population problem and the overall development for newly independent Singapore:10 “If we are to raise our standard of living, get away from poverty, filth and squalor, we must not only use modern science and technology to build the things we want. But also to prevent us from dragging ourselves to the ground by having too many in the family to care for.”

In January 1966, the Singapore Family Planning and Population Board (SFPPB) was established to carry out all family planning and population matters in Singapore. It took over the family planning clinics managed by the SFPA, the majority of which were located within Maternal and Child Health (MCH) centres, and launched the National Family Planning and Population Programme that aimed to make family planning advice, supplies, and clinical services known and accessible to all.11

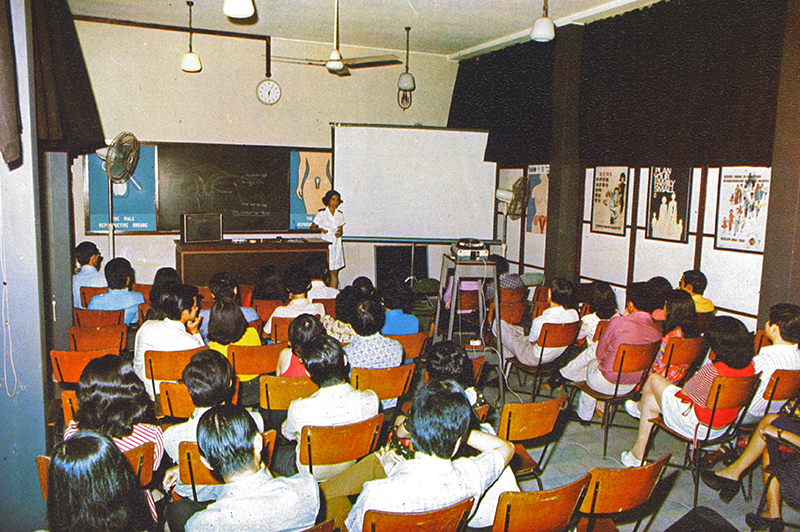

The family planning message was amplified through the mass media. Articles on the topic were published in magazines and newsletters, forum debates were televised, and publicity materials such as coasters, booklets, key chains and car stickers were distributed. Exhibitions held in the city and rural areas were “free and frank, including anatomy, physiology and methods of contraception for all to see”. There were no restrictions on age, sex, or marital status, and everyone was free to attend. Trained medical workers educated and counselled women on family planning methods at the MCH centres and government hospitals, as well as the women they visited at home for postnatal treatments.12

Changing the mindsets of people towards family planning was a challenge. An early project aimed at getting women to accept intra-uterine devices (IUDs) as the main contraceptive method met with little success due to misconceptions that the device could be lodged in the lungs or travel to the mouth. Thus, instead of going to hospitals and family planning clinics for family planning advice, these women were now heading there for IUD removals. The Family Planning Board then changed tactics by offering women a “menu card” of contraceptives to choose from, which proved more favourable. Besides IUDs, options included contraceptive pills, sterilisation, diaphragms, vaginal tablets, condoms and even the rhythm method.13

While family planning involved both the husband and wife, it was often left to the wife to bear the responsibility. But she was not always allowed to make decisions about this on her own. Uma Rajan, a clinical doctor at a MCH centre, recalled having to help women in such situations in the 1960s. She said: “Most of the men did not like to use contraceptives of any kind, so it was left to the women.” “If the husbands found that [a] method [was] not suitable, they must be prepared to change even if it was comfortable for the woman,” she added. Women also had to consider the demands of her in-laws for more children, especially sons.14

Besides contending with prevailing social and gender norms, medical staff had to also educate perplexed patients on how to use certain contraceptives. Midwife Mary Hee once attended to a woman at a rural clinic who explained that her husband complained of discomfort when using condoms. The midwife eventually found out that it was because the man was wearing the condom the entire day.15

While family planning counselling sessions could sometimes be frustrating, both for the medical officers and the women seeking advice, these sessions were also an opportunity for women to confide in midwives privately about issues they faced. Hee recalled counselling a patient who eventually revealed her husband’s sexual abuse.16 For some women, these family planning clinics not only offered family planning advice but were also a sanctuary where they could seek solace and help.

Yet, Birth Rates Continue to Rise

Although birth rates decreased from 29.5 to 22.1 births per thousand from 1966 to 1971, there was no celebrating yet as the number of women in their early 20s would more than double from 1966 to 1975, resulting in more births.17

The National Family Planning and Population Programme’s second five-year plan, spanning 1971 to 1976, now targeted newlyweds and married women from low socioeconomic backgrounds, as well as promoted sterilisation as the best family planning method for families with at least two children.18

While sterilisation was legalised in 1970, the procedure was liberalised with the Voluntary Sterilisation Act of 1974. Applicants could now opt for sterilisation at an affordable price of $5 if they had at least two living children instead of three.19 They also no longer had to be interviewed by the Eugenics Board – a five-member team constituted under the Voluntary Sterilisation Act to authorise sterilisation treatments – before undergoing the procedure, and the waiting time was shortened.20

The push to promote sterilisation faced some backlash. A number of family planning nurses were “accused of using tactless tactics” when persuading eligible mothers to undergo the procedure. As one mother told the New Nation: “It can be very annoying and embarrassing – when one has not fully recuperated – to have a nurse who keeps on harping on the advantages of sterilisation.”21

Medical staff had the challenging task of being the messenger of government policies that encroached into citizens’ private lives. Sumitera Mohd Letak, a midwife in the 1970s, recounted in an oral history interview: “I have colleagues who have been really abused for that. [Patients would say] ‘Hey, who are you to tell me? Who are you to tell me that I can’t afford to feed my baby and all that’. So the choice of words is very important.”22

Despite the difficulties, family planning services continued with the addition of a convenient and confidential telephone information service. Additionally, abortion, first legalised in 1969, was made more accessible with the Abortion Act of 1974.23

A new SFPPB Training Unit, set up in 1972, was tasked with training new and existing staff to be adept in more “sophisticated” motivation techniques in a bid to reduce birth rates.24 As former training education officer Jenny Heng explained, the staff motivating patients were nurses, midwives and doctors, whose primary training was in medicine. The new Training Unit brought sorely needed communication and sociological perspectives that would make the process of encouraging women to accept family planning more friendly or appealing.25

Two Is Enough

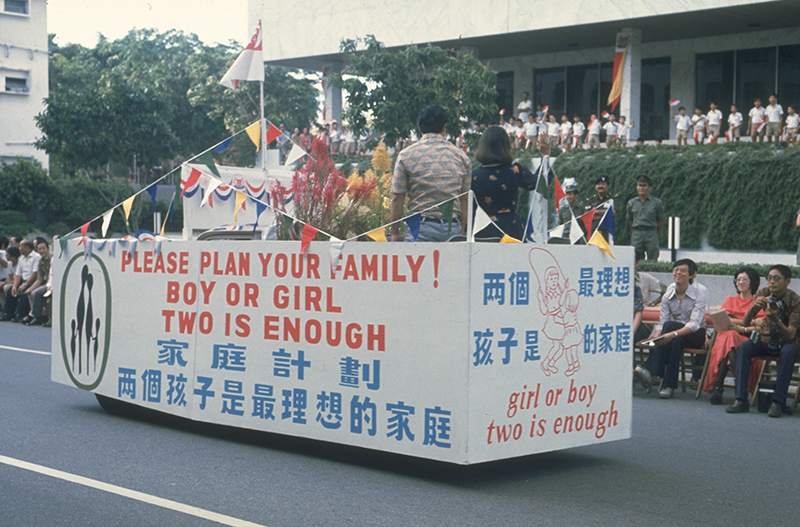

In 1972, the two-child family norm was pushed for the first time and publicity became a year-round affair rather than during specific campaign periods.26 Instead of slogans like “Singapore Wants Small Families”, the message now said “Girl or Boy, Two Is Enough”, and was blasted through all forms of mass media and emblazoned on collectibles. The Family Planning Board even launched two songs, “Will You Find Time To Love Me” and “It’s No Joke”, encouraging couples to delay marriage, delay having their first child and to space out their children.27

One of the benefits put forth by the government for having no more than two children was so that each child would get a “bigger share of the pie”. This was a message that struck home for many. In a study on population policies conducted by researchers between 1974 and 1976, a housewife who was interviewed explained in simple and clear terms how fewer children meant more food for each of them: “If you have only one child, you buy one dollar’s worth of liver for him, and he’ll get one dollar’s worth of liver. If you have two children, each will get only fifty cents’ worth of liver!”28

Existing social policies got a boost, and new social disincentives were introduced to change people’s attitudes towards having large families. For instance, maternity leave was further restricted, with paid maternity leave granted only for the first two children. From 1973, the primary school registration process was also changed, resulting in the fourth child and beyond having lower priority in the queue for the school of their choice – unless one of their parents was sterilised.29

Tax relief for mothers was also reduced and allowed only for the first three children compared to the previous five. However, the most impactful disincentive, especially for lower income families, was the increase in delivery fees. From August 1973, a system of progressive charges was introduced, with fees increasing at different rates based on ward class. By 1975, fees for class C patients had increased much more compared to those in class A or B wards. For the fourth child, for example, patients in class C wards had to pay $120 more compared to their third child, while those in class A and B wards only had to pay $60 more.30

However, studies have shown that that economic penalties and disincentives had a limited effect on families from the low-income working class who tended to have large families. According to researchers, a history of occupational insecurity led them to want more children as “children may prove to be their main security in the future”. These families also did not relate to the aspirations of social mobility that the two-child family concept promoted. When asked about the occupation or trade they wished for their children to pursue, one respondent interviewed replied: “I can’t afford to think of the future. I just live on and see.”31

And Then There Were Three

In 1975, less than a decade since the SFPPB was formed, the fertility rate dropped to replacement level in Singapore. Between 1966 and 1983, the birth rate decreased from 29.5 per thousand to 17.1.32 Experts and those involved in the family planning programme have cited multiple factors for this successful decline, including close cooperation among other government agencies in the implementation of family planning policies, improvements in socioeconomic conditions and the increased participation of women in the labour force.33

In the early 1980s, there was an attempt to reverse this trend of falling fertility but in a very targeted way by focusing on particular groups of women. In his 1983 National Day Rally speech, Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew highlighted what he saw as the problem of a declining quality of Singapore’s future labour force since well-educated women were having fewer children than their less-educated counterparts.34

“[W]e shouldn’t get our women into jobs where they cannot, at the same time, be mothers…,” he noted. “You just can’t be doing a full-time heavy job like that of a doctor or engineer and run a home and bring up children. It is tough… women, 40 years and over… unlikely to marry and have children.”35

This was the prelude to a significant change in family and population planning in Singapore: the introduction of pro-natalist policies specifically targeted at well-educated women only. The controversial Graduate Mothers Scheme was introduced in 1984, which included giving priority to the children of university-educated mothers who had three or more children during the primary school registration exercis These mothers would alsoH enjoy more tax deductions. However, the scheme was rescinded a year later as many women expressed unhappiness over the discriminatory policies.36

Its work done, the SFPPB closed in 1986. That year, Singapore’s total fertility rate (the average number of births per women) fell to 1.42, well below the replacement level of 2.13. The board had done its work a little too well. The continued falling birth rates became a cause for concern for the government, prompting the establishment of the Inter-Ministerial Population Committee in 1984 to review the existing population control programme.37

In a 1986 ministerial speech at Nanyang Technological Institute, First Deputy Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong spoke about Singapore’s declining birth rate problem and its consequences for the nation’s economic growth and security. He also highlighted the “grave problem” of an ageing population. “You may say that your children can support you, but bear in mind at the rate we are going, many Singaporeans will have only one or even not a single child in their life time…,” he said. “Singapore has no natural wealth. The only way for the Government to raise the required revenue to take care of the older population is to levy more taxes on those who are working. And they will squeal.”38 Hence in 1987, the “Stop at Two” slogan was replaced by “Have three or more, if you can afford it”.39

.png)

Since then, Singapore has been trying to get the birth rate up. Baby bonuses, tax rebates, childcare subsidies, earlier access to Housing and Development Board flats, and childcare leave and paternity leave are just some of the measures in place today to encourage Singaporeans to have more children.40 But Singapore’s total fertility rate has continued to trend downwards over the decades. In 2021, it was 1.12.41

The falling birth rate continues to be a matter of concern, engendering issues of not just a rapidly ageing population but also issues of immigration in recent decades, which have created tensions in the social fabric. It remains to be seen if the pro-natalist policies can achieve anything approaching the level of success as the anti-natalist National Family Planning and Population Programme of the 1960s and 1970s.

Andrea Kee is an Associate Librarian with the National Library of Singapore, and works with the Singapore and Southeast Asia collections. Her responsibilities include collection management, content development as well as providing reference and research services.

Andrea Kee is an Associate Librarian with the National Library of Singapore, and works with the Singapore and Southeast Asia collections. Her responsibilities include collection management, content development as well as providing reference and research services.NOTES

-

Yap Mui Teng, “Singapore: Population Policies and Programs,” in The Global Family Planning Revolution: Three Decades of Population Policies and Programs, ed. Warren C. Robinson and John A. Ross (Washington, DC: World Bank, 2007), 206. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 363.9091724 GLO) ↩

-

Mrs Hena Sinha, oral history interview by Daniel Chew, 2 November 1983, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 11 of 13, 28:06, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000354), 158. ↩

-

Saw Swee-Hock, Population Policies and Programmes in Singapore (Singapore: ISEAS Publishing, 2016), 6. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 363.96095957 SAW) ↩

-

Yap, “Singapore: Population Policies and Programs,” 203; Dorothy F. Atherton, “Birth Control Clinics,” Singapore Free Press, 28 October 1961, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Sinha, oral history interview, 2 November 1983, 160–61; “‘Desperate’ Mothers Seek Aid,” Singapore Free Press, 3 May 1950, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Tragic Cases of Singapore’s Unwanted Children,” Malaya Tribune, 21 June 1950, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Yap, “Singapore: Population Policies and Programs,” 203; Saw, Population Policies and Programmes, 9. ↩

-

Saw, Population Policies and Programmes, 9; Saw Swee-Hock, Changes in the Fertility Policy of Singapore (Singapore: Times Academic Press for the Institute of Policy Studies, 1990), 1–2. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 304.66095957 SAW) ↩

-

Family Planning in Singapore (Singapore: Printed by Govt. Printer, 1966), 2, 14. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 363.96095957 FAM) ↩

-

Lee Kuan Yew, “Text of Speech by the Prime Minister, Mr. Lee Kuan Yew, When He Officially Opened the New P.S.A. Blair Plain Housing Estate On 8th October”, speech, P.S.A. Blair Plain Housing Estate, 8 October 1968, transcript, Ministry of Culture. (From National Archives of Singapore, document no. lky19681008) ↩

-

Dolly Irene Pakshong, The Singapore National Family Planning and Population Programme, 1966–1982 (Singapore: Singapore Family Planning & Population Board, 1983), 2. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 304.66095957 PAK); Saw, Population Policies and Programmes, 12. ↩

-

Margaret Loh, The Singapore National Family Planning and Population Programme, 1966–1973 (Singapore: Singapore Family Planning & Population Board, 1974), 7. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 363.96095957 LOH); K. Kanagaratnam, “Singapore: The National Family Planning Program,” Studies in Family Planning 1, no. 28 (1968): 9. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Kanagaratnam, “National Family Planning Program,” 4, 7. ↩

-

Mrs Uma Rajan, oral history interview by Patricia Lee, 11 December 1999, MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 2 of 4, 31:36, National Archives of Singapore, accession no. 001985) ↩

-

Mary Hee Sook Yin, oral history interview by Patricia Lee, 20 September 1999, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 8 of 11, 29:12, National Archives of Singapore, accession no. 002206), 135–36. ↩

-

Mary Hee Sook Yin, oral history interview by Patricia Lee, 20 September 1999, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 9 of 11, 30:25, National Archives of Singapore, accession no. 002206), 141–42. ↩

-

Pakshong, Singapore National Family Planning and Population Programme, 2–3; Margaret Loh, The Two-child Family: A Social Norm for Singapore (Singapore: Singapore Family Planning and Population Board, 1982), 6. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 301.5 LOH) ↩

-

Wan Fook Kee and Margaret Loh, Second Five-Year Family Planning Programme 1971–1975. (Singapore: Singapore Family Planning and Population Board, 1982), 1–2 (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 301.426095957 WAN); Singapore Family Planning and Population Board, Annual Report 1973 (Singapore: Singapore Family Planning and Population Board, 1973), 44. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 301.426 SFPPBA) ↩

-

Saw, Population Policies and Programmes, 68; Mary Lee Frances Dowsett, “Sterilisation – Cheapest Contraceptive Method,” New Nation, 28 July 1972, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Saw, Population Policies and Programmes, 65, 68. ↩

-

“Tactless Nurses…,” New Nation, 13 September 1976, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Sumitera Mohd Letak, oral history interview by Patricia Lee, 29 July 1997, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 7 of 9, 28:47. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. 001915), 93. ↩

-

Wan Fook Kee and Margaret Loh, “Fertility Policies and the National Family Planning and Population Programme,” in Public Policy and Population Change in Singapore, ed. Peter S.J. Chen and James T. Fawcett (New York: Population Council, 1979), 102. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 301.3295957 PUB); Saw, Population Policies and Programmes, 44–45, 50–51. ↩

-

Singapore Family Planning and Population Board, Annual Report 1973, 51; “Plan to Attract the Stay Away Women,” Straits Times, 5 July 1972, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Jenny Heng, interview, 23 May 2022. ↩

-

Singapore Family Planning and Population Board, Annual Report 1972 (Singapore: Singapore Family Planning and Population Board, 1973), 37. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 301.426 SFPPBA) ↩

-

Kanagaratnam, “National Family Planning Program,” 11; Saw, Population Policies and Programmes, 29; “Sing a Song or Two for Family Planning,” Straits Times, 4 February 1981, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Aline K. Wong and Janet W. Salaff, “Planning Births for a Better Life: Working-class Response to Population Disincentives,” in Public Policy and Population Change in Singapore (New York: Population Council, 1979), 121. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 301.3295957 PUB) ↩

-

Saw, Population Policies and Programmes, 82–83; Margaret Loh, Beyond Family Planning Measures in Singapore: A Country Paper Submitted for the IGCC Workshop on Reducing Fertility through Beyond Family Planning Measures (Singapore: Singapore Family Planning & Population Board, National Family Planning Centre, 1976), 10. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 301.426095957 LOH) ↩

-

Loh, Beyond Family Planning Measures in Singapore, 24; Saw, Population Policies and Programmes, 84. ↩

-

Wong and Salaff, “Planning Births for a Better Life,” 120–22. ↩

-

Yap, “Population Policies and Programs,” 205; Pakshong, Singapore National Family Planning and Population Programme, 2, 37. ↩

-

James T. Fawcett and Siew-Ean Khoo, “Singapore: Rapid Fertility Transition in a Compact Society,” Population and Development Review 6, no. 4 (1980): 558; “Singapore Fertility Attains Record Low; Antinatalist Policies are Questioned”, International Family Planning Perspectives 13, no. 1 (1987): 29. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

J. John Palen, “Fertility and Eugenics: Singapore’s Population Policies,” Population Research and Policy Review 5, no. 1 (1986): 5. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

“The Things PM Says,” Straits Times, 15 August 1983, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Palen, “Fertility and Eugenics,” 7; “Graduate Mum Scheme To Go,” Straits Times, 26 March 1985, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Saw, Population Policies and Programmes, 159, 210, 219. ↩

-

Goh Chok Tong, “Speech by Mr Goh Chok Tong, First Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Defence, at The Nanyang Technological Institute (NTI) Forum, on Monday, 4 August 1986 at 7.30 PM”, speech, Nanyang Technological Institute (NTI) Forum, 4 August 1986, transcript, Ministry of Communications and Information. (From National Archives of Singapore, document no. gct19860804s) ↩

-

Lenore Lyons-Lee, “The ‘Graduate Woman’ Phenomenon: Changing Constructions of the Family in Singapore,” Sojourn: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia 13, no. 2 (1998): 314. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Saw, Population Policies and Programmes, 157–207; Rei Kurohi, “MPs Raise Concerns over Changes to Law on Childcare Benefits and Baby Bonus Scheme,” Straits Times, 2 August 2021. (From Factiva via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Amelia Teng, “Budget Debate: Singapore’s Birth Numbers Last Year Similar to 2020, Higher than Expected,” Straits Times, 2 March 2022. (From Factiva via NLB’s eResources website) ↩