Loke Wan Tho: The Man Who Built Cathay

While best known as a giant in the movie business in Malaya, Loke Wan Tho was also passionate about bird photography and the arts.

By Bonny Tan

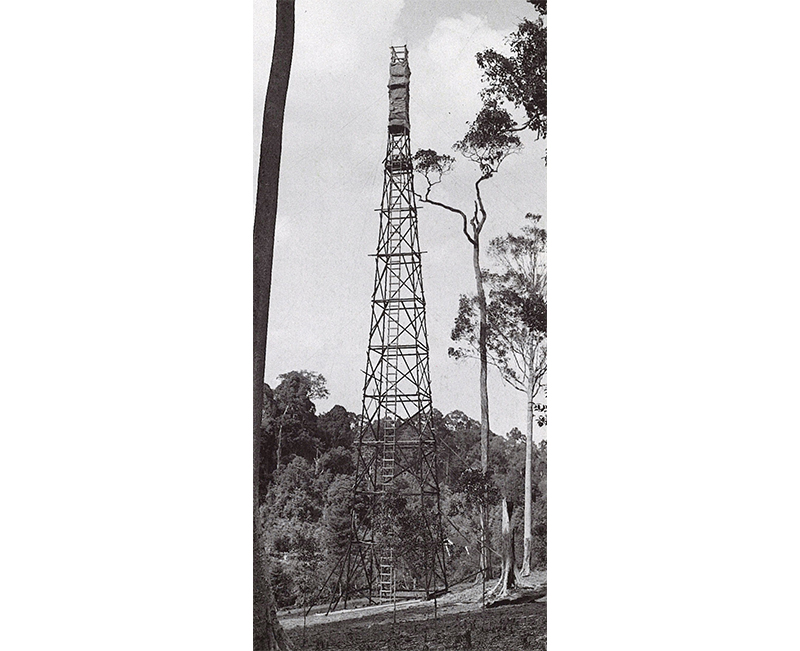

Armed with just a camera and a seeming lack of fear, cinema magnate Loke Wan Tho spent hours on the precarious platform at the top of a 12-storey (40 m) wooden tower, not dissuaded by the burning sun or the fact that the tower swayed beneath him in strong winds. At one point, he even endeavoured to sit out a storm while on the platform, though he quickly thought better of it after he became giddy. Why was one of Malaya’s richest men risking his life some 40 m above the ground? Loke was on a quest: to snap the perfect photograph of a white-bellied sea eagle.

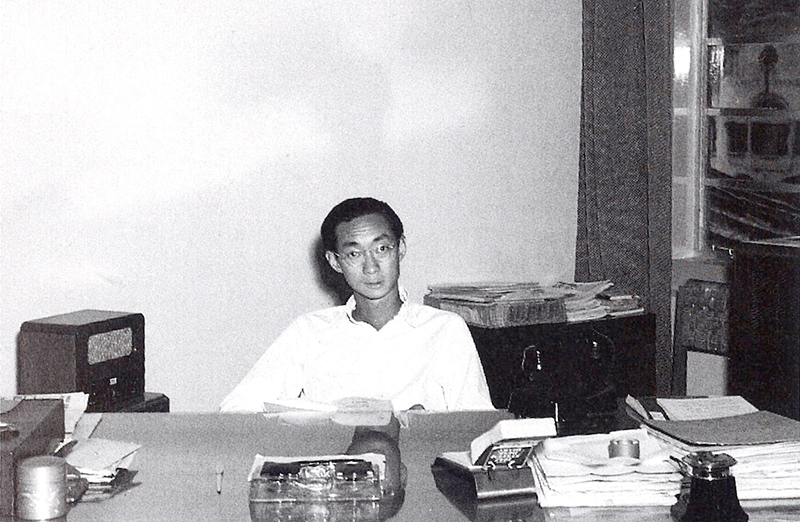

Loke Wan Tho, as this anecdote reveals, was not your usual business tycoon. With the closure of Cathay Cineplex in June 2022, it is timely to throw the spotlight on Loke, who helmed Cathay and its associated businesses for over two decades before his untimely death at the age of 49.

A Privileged Upbringing

Loke was born on 14 June 1915 in Kuala Lumpur, Malaya, the ninth scion of prominent merchant Loke Yew (born Wong Loke Yew) and his fourth wife, Lim Cheng-Kim. Loke Yew was an impoverished 13-year-old who arrived in Singapore from Guangdong, China, around 1858. Dropping his surname Wong in an attempt to improve his luck, Loke Yew made his fortune through tin-mining before expanding into rice mills, real estate, the motor industry and steam trading. His businesses spanned Perak, Selangor, Negeri Sembilan, Singapore and beyond. By the turn of the 20th century, Loke Yew had become one of the richest men in Malaya.1

He also donated generously to social causes such as schools and hospitals, and became a respected business leader in the Chinese community, not only in Malaya but also in Hong Kong, China and Taiwan.2 His sudden death in 1917 from malaria left the two-year-old Loke Wan Tho with wealth and in due time the weight of business and philanthropic responsibilities.3

Afflicted with poor health, the young Loke was initially educated by a governess and only began attending school at age 12.4 After a short stint at Victoria Institution in Kuala Lumpur, a school co-founded by his father, his doctor advised him to move to a place with a better climate to improve his weak constitution. His entire family thus left for Europe in 1929 where Loke continued his education at prestigious schools, excelling in both sports and academics.5

He enrolled at Chillon College in Montreux, Switzerland, a boarding school popular with wealthy British colonialists. Set in the scenic alps, the mountain air seemed to do Loke good. He became captain of the school soccer team and set the 1932 long-jump record in the Swiss county of Vaud – a record he held for over 30 years. His athleticism was noticed by the British Olympic sprinter, Harold Abrahams (the subject of the movie Chariots of Fire), who encouraged Loke to train professionally. Unfortunately, a broken ankle put paid to his athletic dreams.6

Although Loke knew that he would have to eventually run his father’s business, he studied English literature “for pleasure, if not for profit”.7 In 1936, Loke graduated from King’s College, Cambridge, with an honours degree in English literature and history.8 He subsequently furthered his studies at the London School of Economics, where he excelled academically and also as an athlete and leader, becoming the school’s badminton champion in 1937 and 1938.9

A Film Mogul

Meanwhile, Loke’s mother, Mrs Loke Yew (née Lim Cheng-Kim), and a relative, Khoo Teik Ee, were busy setting up the foundations for the family cinema business. Mrs Loke Yew had incorporated Associated Theatres on 18 July 1935 with Khoo and an Englishman, Max Baker, who introduced the first talkies to Singapore in 1929. On 5 August 1936, she established the 1,200-seat Pavilion in Kuala Lumpur, and on 3 October 1939, the iconic Cathay Cinema in Singapore opened its doors.10

Loke returned to Singapore in 1940 and the next year, the main tower of the 83.51-metre-tall Cathay Building was completed comprising apartments that offered a panoramic view of Singapore and the sea.11 (Cathay Cinema and Cathay Restaurant were located in the front block.)

The Japanese invasion of Singapore in December 1941, however, forced a change of plans. In February 1942, Loke boarded the Nora Moller to escape the war. Unfortunately, the vessel was bombed off the Strait of Banka and Loke suffered severe burns to his body and was also temporarily blinded. Rescued by the Australian cruiser Sydney, Loke was taken to a hospital in Batavia (now Jakarta). After a few weeks of recuperation, Loke left for India against his doctor’s orders as he had predicted – rightly – that Java would soon suffer the same fate as Singapore. He then spent the war years in India.12

During the Japanese Occupation, Cathay Building was used as the local branch of the Japanese Broadcasting Department and the cinema, renamed Dai Toa Gekkizyo (Greater East Asian Theatre), screened Japanese propaganda films. After the Japanese surrender in 1945, Loke returned to Singapore and Cathay became the first cinema to start screening movies in post-war Singapore, reopening on 23 September 1945.13

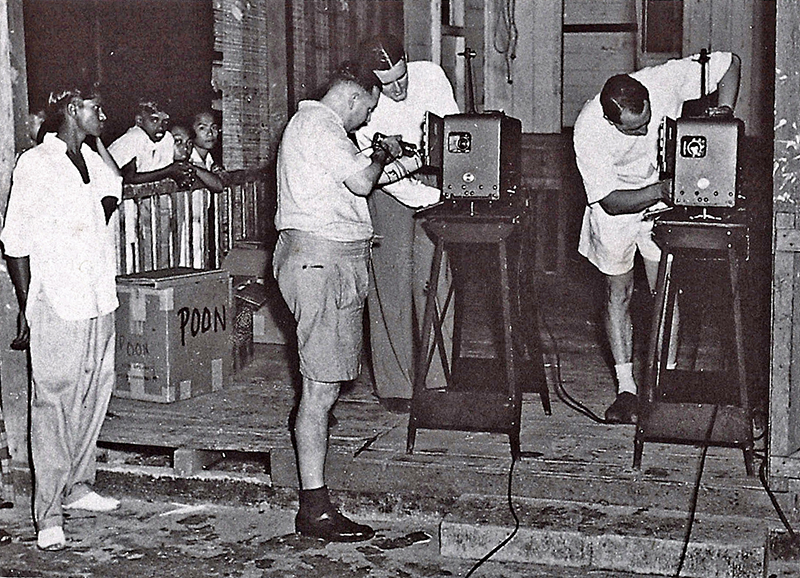

In 1947, Loke set up Caravan Films – a joint venture with Overseas Cinematograph Theatres – to bring film and entertainment to estates and villages throughout Singapore and Malaya by using vans carrying projectors, sound equipment and screens. By 1948, Cathay Organisation had cinemas operating in Penang, Borneo and Thailand.14 By then, Loke was known as one of the wealthiest men in Singapore.

In 1953, Loke established Cathay-Keris Studio with Ho Ah Loke, the managing director of Keris Film Productions. Competing against its main rival, Shaw Brothers, Cathay-Keris produced mostly Malay films, including Pontianak (1957), made in both Malay and Chinese. Cathay-Keris’s Hang Jebat (1961) is still considered one of the best screenplays of the legend of the titular Malay warrior.15

To penetrate the Chinese film market, Loke acquired Yung Hwa Studio in Hong Kong in 1955 for film production and distribution, and subsequently formed the subsidiary, Motion Picture and General Investment Co Ltd (MP&GI), in Hong Kong to run Yung Hwa. MP&GI was a significant player in the Hong Kong market, and made about 250 films between 1956 and 1970.16

Loke studied the art of filmmaking as much as the commercial aspects of running a film business. He travelled to India to better understand the craft and invited Hollywood stars to coach his studio’s actors.17 The efforts bore fruit in 1957 when MP&GI became the first Hong Kong studio to garner a prize at the Fourth Asian Film Festival in Tokyo.

Loke’s other appointments included the chairmanship of Malayan Banking, Singapore Telephone Board and Malayan Airways. He was also the director of companies such as Great Eastern Life Assurance, Malaya Tribune Press and Sime Darby. In the public sector, Loke served as the pro-chancellor of the University of Malaya and was the first chairman of the board of the National Library in Singapore. For his contributions to the early Malayan film industry, Loke was conferred a Dato by the Yang di-Pertuan Agong in 1961.18

A Bird Lover

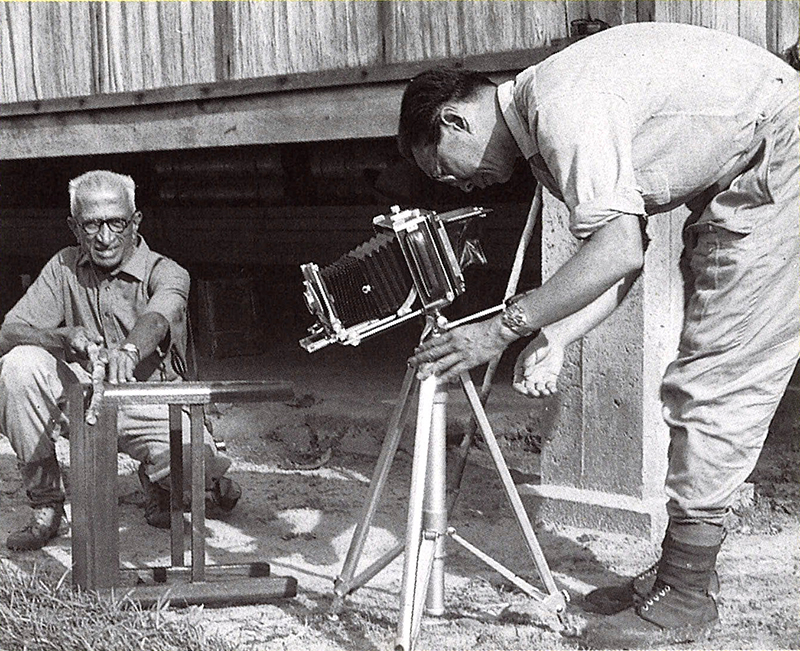

In addition to being a successful businessman, Loke was also a serious nature lover. His passion for ornithology went hand in hand with that of photography. Introduced to the camera at age 12, Loke clinched his first photographic award for a photograph of the Matterhorn just three years later. During a summer vacation while still a student in Cambridge, Loke had the opportunity to sharpen his photography skills under master photographer G.L. Hawkins.19

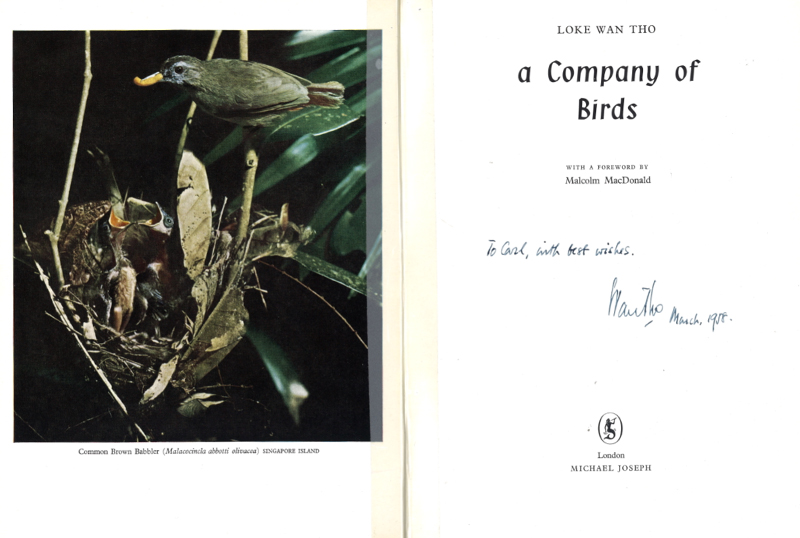

Much of Loke’s summer vacations were spent at Pembrokeshire where the Welsh coastland, enlivened by a great variety of coastal birds, ignited in the young Loke a fascination for birds. He later published a book titled A Company of Birds (1957), showcasing his photographs of birds in India, New Guinea and Malaya.20

During one of these jaunts to Pembrokeshire, Loke managed to capture a raven attacking a heron on film. As Singapore’s former Governor-General Malcolm MacDonald poetically noted in his foreword to Loke’s book, A Company of Birds: “[Loke] watched a Raven work off a fit of rage by chasing a Heron. When the pursuit ended the Heron was still free, but Loke was a captive.”21

Loke’s love for birds was enhanced during the years he spent in India while Singapore was under Japanese rule. There, Loke was introduced to the Indian ornithologist Salim Ali, a leading figure in the field. Almost 20 years his senior, Salim became Loke’s mentor, taking him on expeditions to survey birds in the rugged landscapes of Kutch (in Gujarat) and Kashmir. As Loke was unable to return home due to the war, he remained in India for a couple of years and the two men became firm friends.22

Conditions in the field were primitive and Loke confessed that outdoor living without access to a water-closet was not something he would “become wholly accustomed” to, but he recognised that “these petty discomforts were a cheap price to pay for the opportunity to study bird life at close quarters”.23

The experience not only taught Loke how to accurately observe birds in their natural habitats, but also to take concise notes and preserve specimens for museums. It was through this study of birds that Loke found his diverse passions – for books, photography and outdoor adventures – meld into a single obsession. In the mid-1950s, Loke funded two expeditions to Sikkim, led by Salim, resulting in the publication Birds of Sikkim (1962), authored by the latter.24

Despite his busy work schedule, Loke returned to India frequently to photograph birds with Salim, travelling to Kashmir, Sikkim and the Himalayas. These expeditions extended into New Guinea in 1952, where Loke became one of the early bird photographers on the island. He even ventured to far-flung locations such as Finland near the Arctic circle to pursue his passion.25

Loke’s images of birds were the result of hours of patience waiting in dangerous and awkward positions, or from trekking through treacherous jungle and mountainous terrain. In his foreword to Loke’s book, A Company of Birds, MacDonald gave a firsthand account of Loke’s dedication, based on the fact that Loke’s 40-metre-high tower was built in MacDonald’s garden in Johor.

“At weekends, Loke would arrive [from Singapore] to take his pictures,” MacDonald wrote. “Hour after hour he sat aloft on his small platform. The tropical sun almost roasted him alive, his camera had to be worked from an angle which nearly sent him crashing headlong from his perch.” As MacDonald noted, a strong wind would make the tower sway “like the mast of a ship on a heaving ocean”. Once, Loke tried to ride out a storm on the platform but “had to descend hastily because he got giddy. It was an extraordinary demonstration of crazy heroism”.26

Loke’s efforts paid off with dramatic photographs of the white-bellied sea eagles. The images were later used as a template for the crest design of the Singapore Island Country Club where Loke had served as its first president.27

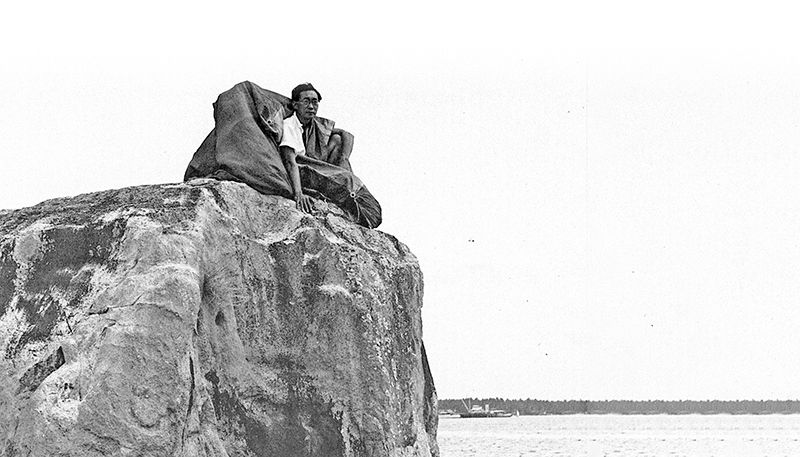

Some of Loke’s photographs of Malayan birds were also made into Christmas cards and postcards. Indeed, the image on the back of the Singapore one-dollar note in the bird series is believed to have been based on Loke’s 1952 photographs of black-naped terns on Squance Rock (also known as Loyang Rock) off Changi.

In 1954, Loke was made an Associate of the Royal Photographic Society in 1954. He was conferred the Fellowship of the Photographic Society of America in 1961, on top of other awards in the US and the UK.28

Unsurprisingly, Loke was a staunch supporter of various nature organisations such as the International Council for Bird Preservation, and the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. He also contributed actively to the Malayan Nature Society, becoming an honorary life member in 1961 and serving as its vice-president in 1962.29

Loke was also a connoisseur of the arts. He and his second wife Christina Lee shared a love for Chinese ceramics. In 1963, Loke donated 500 photographs of birds, people and places to Malaysia’s National Art Gallery. The collection included famous images by Armenian-Canadian photographer Yousuf Karsh and those by well-known American landscape photographer and environmentalist Ansel Adams.30

An Untimely Demise

Running Cathay Organisation and its associated businesses proved challenging in the face of stiff competition from Shaw Brothers. The company also had to deal with the increasing political tumult in post-war Singapore as well as financial losses and bleeding business investments.31 By 1958, as the film business as a whole faced a decline, Loke’s foreign partners began withdrawing their financial support and he felt the impact. Loke disclosed that for some years in the mid-1950s, he did not draw any salary.32

In 1959, Loke consolidated his stable of companies – Associated Theatres, Loke Theatres and International Theatres – under Cathay Organisation, with plans to go public by the following year.33 Unfortunately the public listing was never realised in his lifetime.

Adding to Loke’s woes, his marriage to Christina Lee ended in an acrimonious divorce in 1962. He was, however, able to find love soon after and in September the following year, he married Mavis Chew.34

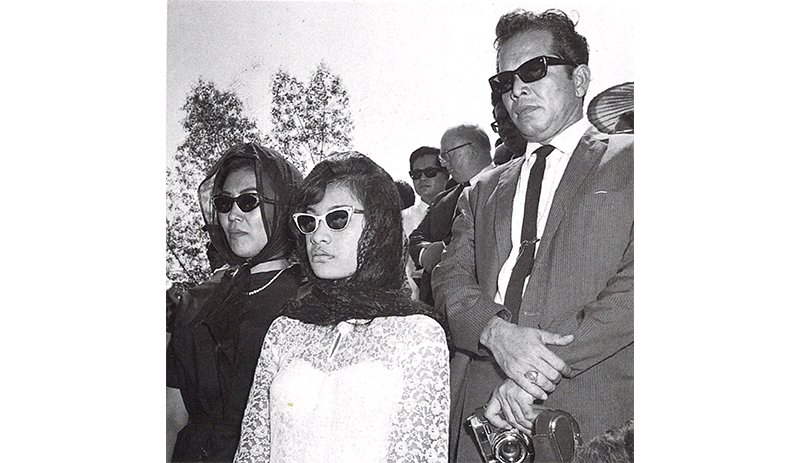

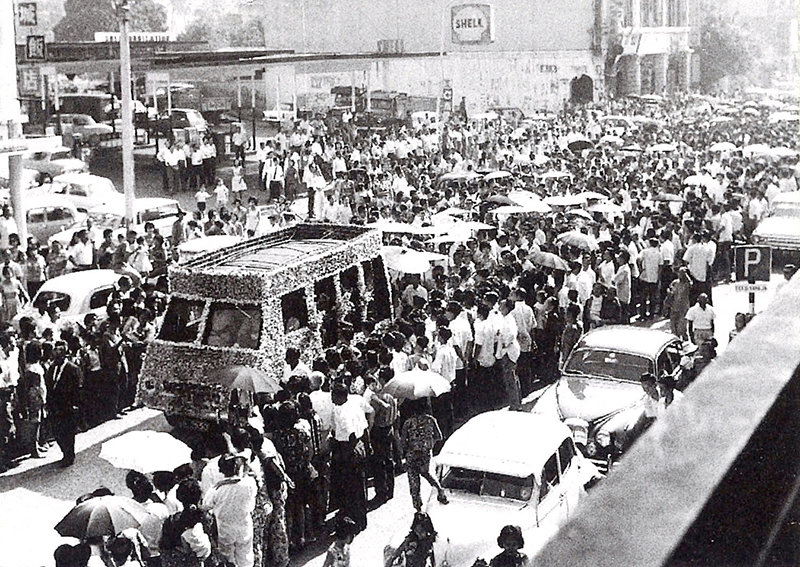

Sadly, barely nine months later, the couple lost their lives when the plane they were on crashed in Taichung, Taiwan, shortly after takeoff on 20 June 1964. All 53 people on board died. Loke and Chew were returning home from the 11th Asian Film Festival, where Loke had received Golden Accolades awards on behalf of three Cathay Organisation stars.35 He had just turned 49 a few days before.

A Lasting Legacy

In 1965, Loke’s mother donated the Dr Carl Alexander Gibson-Hill Collection to the National Library, which augmented the newly opened Southeast Asia Room that would house resources relating to the region. Gibson-Hill was the last expatriate director of the National Museum and a close friend of Loke’s. Loke had received Gibson-Hill’s collection of rare books upon the latter’s death, just a year prior to his own passing. Considered at the time as “one of the most outstanding private collections of its kind in this part of the world”, the collection includes 25 of Loke’s personal titles on photography.36

The Loke Wan Tho Memorial Library was opened in 1972 at Jurong Bird Park, with a $100,000 donation by Loke’s mother and his sisters as well as his collection of books on birds, photographs and tape recordings of bird songs.37

Loke’s name also lives on in Wan Tho Avenue in Sennett Estate and the Loke Wan Tho Gallery at the Selegie Arts Centre.38 The gallery was launched in 1996 thanks to his contributions to the Photographic Society of Singapore and to commemorate his breadth of work in the field.39 In death, as in life, Loke has continued to make his mark.

More resources on Loke Wan Tho and Cathay are available here.

Bonny Tan is a former Senior Librarian at the National Library, Singapore. She currently lives in Vietnam with her family and is a regular contributor to BiblioAsia.

Bonny Tan is a former Senior Librarian at the National Library, Singapore. She currently lives in Vietnam with her family and is a regular contributor to BiblioAsia.NOTES

-

Lim Kay Tong, Cathay: 55 Years of Cinema (Singapore: Landmark Books, 1991), 8. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 791.43095957 LIM); “Death of Mr Loke Yew,” Straits Echo, 24 February 1917, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Grave Concerns for the Past,” New Sunday Times, 7 January 2007; Lim, Cathay, 8. ↩

-

“Dr Loke’s Son Welcomed,” Straits Budget, 27 January 1937, 10. (From NewspaperSG); Raphael Millet, Singapore Cinema (Singapore: Editions Didier Millet, 2006), 22. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 791.43095957 MIL) ↩

-

Ian Mok-Ai, “Behind the Veil of Vast Wealth Lies an Artistic, Lonely Man with a Sense of Humour,” Singapore Free Press, 25 November 1960, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Dr Loke’s Son Welcomed”; Lim, Cathay, 12. ↩

-

Millet, Singapore Cinema, 22. ↩

-

Loke Wan Tho, A Company of Birds (London: M. Joseph, 1957), 15. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 598.295 LOK-[GBH]) ↩

-

Lim, Cathay, 14–15; “The Cathay Opens,” Morning Tribune, 4 October 1939, 13. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

The land for Cathay Building was purchased by Loke Wan Tho’s mother. “Movie Magic,” Today, 31 March 2006, 72; “Cathay Flats Ready Early in August,” Sunday Tribune, 4 May 1941, 2. (From NewspaperSG); Lim, Cathay, 15. ↩

-

Loke, A Company of Birds, 13–14. ↩

-

Douglas Amrine, Singapore at Random: Facts, Figures, Quotes and Anecdotes on Singapore (Singapore: Editions Didier Millet, 2011), 142. (From National Library OverDrive); Lim, Cathay, 21. ↩

-

Lim, Cathay, 129–30; Millet, Singapore Cinema, 32, 51; S. Bissme, “Movie Landmarks: The Unforgettable Movies,” Sun, 3 January 2001. (From Factiva via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

“Malayan Movie Millions for H.K.,” Straits Times, 15 June 1956, 4. (From NewspaperSG); Lim, Cathay, 27. ↩

-

Millet, Singapore Cinema, 34. ↩

-

Lim, Cathay, 6; “King Honours 158,” Straits Budget, 11 January 1961, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

The Loke Legacy: The Photography Collection of Dato’ Loke Wan Tho, Balai Seni Lukis Negara Malaysia, National Art Gallery Malaysia, 19 May 2005 to 7 March 2006 (Kuala Lumpur: National Art Gallery, Malaysia, 2006), 19. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RART 779.074595 LOK) ↩

-

Loke, A Company of Birds, 14–15; Allington Kennard, “‘Shooting’ Birds with a Camera,” Straits Times, 10 February 1958, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Loke, A Company of Birds, 11, 15. ↩

-

Loke, A Company of Birds, 15–16; Salim Ali, The Fall of a Sparrow (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1985), 121–23, 127; Loke, A Company of Birds, 15. ↩

-

Loke, A Company of Birds, 16. ↩

-

Loke, A Company of Birds, 15–16; Salim Ali, The Fall of A Sparrow, 127. ↩

-

Loke, A Company of Birds, 22; Pelham Groom, “Off to the Arctic with a Mosquito Net,” Singapore Free Press, 19 May 1958, 4; “Land of the Midnight,” Singapore Free Press, 20 August 1958, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Loke, A Company of Birds, 11. ↩

-

Lulin Reutens, The Eagle & the Lion: A History of the Singapore Island Country Club (Singapore: The Club, 1993), 37. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 367.95957 REU) ↩

-

Lim Boon Tiong, “Dato Loke Wan Tho – An Appreciation,” The Photographic Society of Singapore Monthly Bulletin 10 (1961); “Loke Made an Associate,” Singapore Standard, 18 January 1954, 3; “Dato Loke Awarded Fellowship,” Straits Times, 3 October 1961, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Robert C. Murphy, et al., “Obituaries: Loke Wan Tho,” The Auk 82, no. 2 (April 1965): 322. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

“Loke Photo Gift for National Gallery,” Straits Times, 7 August 1963, 6. (From NewspaperSG); The Loke Legacy, 85, 195. ↩

-

Low Yit Leng, “Picture Playboy,” in Singapore Tatler 13, no. 146 (November 1994): 106. ↩

-

Rahita Elias, “Cathay’s Dream Comes True,” Business Times, 21 April 1999, 16. (From NewspaperSG); Lim, Cathay, 52–53. ↩

-

“Dato Loke Wan Tho Divorce Case Begins,” Singapore Free Press, 13 February 1962, 1; “Dato Loke Weds Quietly in London,” Straits Times, 30 September 1963, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Dato Loke and Wife Die in Air Disaster,” Straits Times, 21 June 1964, 1; “Awards for Cathay Trio,” Straits Times, 20 June 1964, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Books Gift by Mrs Loke Yew Fulfils Wish of Her Late Son,” Straits Times, 11 June 1965, 6. (From NewspaperSG). For more information about the Gibson-Hill Collection, see Bonny Tan, “A Malayan Treasure: The Gibson-Hill Collection,” BiblioAsia 4, no. 3 (Oct 2008): 30–31, https://biblioasia.nlb.gov.sg/vol-4/issue-3/oct-2008/. ↩

-

“Loke Wan Tho Library to Open on Feb 4,” Straits Times, 22 January 1972, 10; “Tribute to Bird Lover Loke,” Straits Times, 5 February 1972, 19. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Winnie Tan, “This Was Once Singapore’s Largest Planned Housing Development: A History of Sennett Estate,” BiblioAsia 18, no. 2 (Jul–Sep 2022): 34–39. ↩

-

Claudette Peralta, “Rochor Gets Its First Arts Home,” Straits Times, 16 November 1996, 23. (From NewspaperSG) ↩