Khoo Hooi Hye, Lim Bong Soo and the Heyday of Malayan Tennis

Two remarkable athletes served up a storm to make Malaya a tennis power to contend with during the interwar years.

By Abhishek Mehrotra

The spectators seated in the pavilion looking out at the tennis courts on Hong Lim Green, home of the Straits Chinese Recreation Club (SCRC), could barely suppress their excitement. It was 24 April 1929 and two of the most talented tennis players ever seen in Malaya were about to go toe to toe in the club’s championship final.1

The match was a replay. A few days earlier, Khoo Hooi Hye and Lim Bong Soo had run each other into the ground; the final had been tied at one set all when, overcome with cramp in the oppressive heat, both had collapsed on court.2 Hong Lim Green, indeed all of Singapore, had rarely witnessed such sporting drama. Now, the two men were back at it.

Three-time defending champion Khoo was a household name, not just in Singapore, but throughout Malaya. Born in Penang in 1901, he had risen through the ranks of the Chinese Recreation Club there while still a teenager. By the age of 16, Khoo was playing exhibition matches with other celebrated players to raise money for the Red Cross during the first World War.3 After dominating the Penang tennis circuit for a number of years, he moved to Singapore sometime in late 1922 or early 1923 and quickly became popular thanks to his sporting prowess and polite, unassuming ways.4

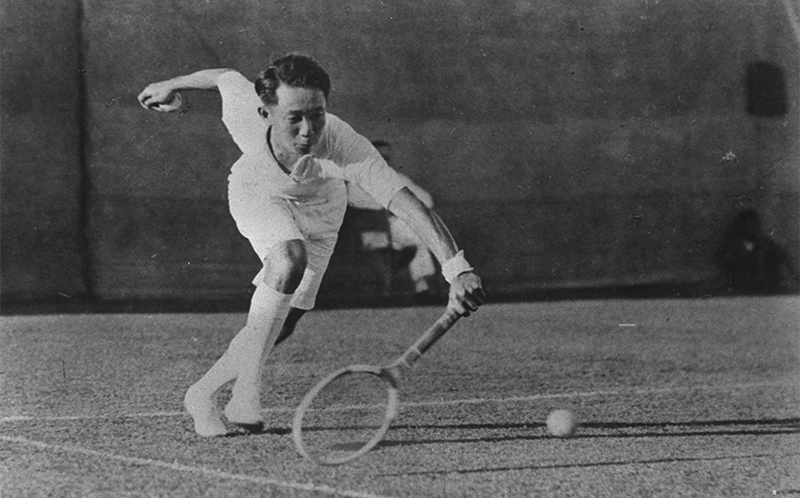

Across the net stood the left-handed Lim, an unlikely tennis player in more ways than one. Standing only five feet tall and slender of frame, he had taken to the game at a fairly advanced age of 18 after seeing Khoo play in the final of the inaugural Malaya Cup in 1921, against then Singapore champion Shunji Nakamura. By 1926, Lim – now a civil servant in the colonial Treasury – was challenging Khoo for the most prestigious tennis titles in Singapore, the Straits, the Malay Peninsula and beyond. The older man had had the final say in most of those early encounters, but today, 24 April 1929, would be his toughest test.

In the first set, Khoo was at his vintage best, mixing “terrific force” with guile, keeping the points short and displaying such mastery of the game that he “literally ran off with the first set”, according to a breathless correspondent. Lim could not win a single game. When Khoo went up 4-2 in the second set, it seemed like all the crowd’s breathless anticipation had come to naught; the defending champion was easily going to clinch yet another title.5

What Lim lacked in stature though, he made up for in unrelenting accuracy, unflagging stamina and steely nerves; the diminutive southpaw roared back to 4-4 and ultimately took the second set 8-6 after saving a match point. Almost spent, Khoo simply could not keep up with his younger opponent in the third set. He went down 5-0 and even though there was a tiny flicker at the end when he won two games in a row, it was Lim who ultimately prevailed at 0-6, 8-6, 6-2.6

“Hooi Hye Beaten. Heroic Struggle with Younger Challenger,” screamed the Malaya Tribune the following day.7 Even by the rarefied standards of Singapore tennis at the time, this had been a titanic clash between two legends – one established; the other, destined.

A Question of Identity

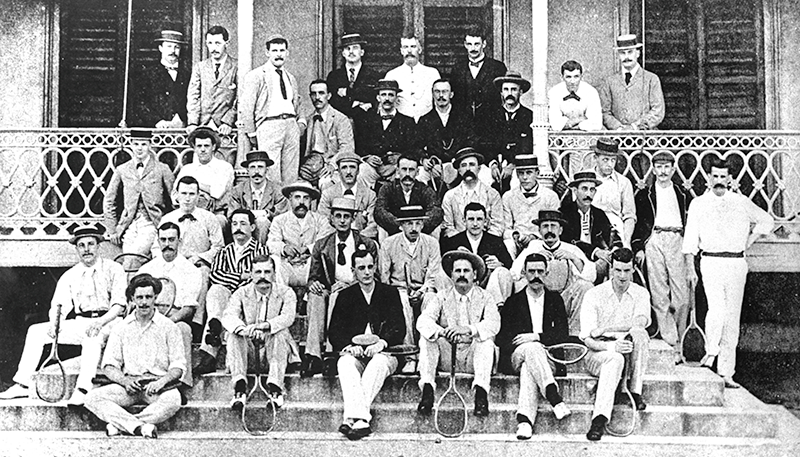

For almost six decades after the arrival of Stamford Raffles, there was barely any organised sport among the Chinese in Singapore. Sport, or physical activity for its own sake, was not permitted in China at the time. Even if it had been, life’s daily struggles in an entrepot still in its infancy barely left any time for leisure. The New Year Sports Day was one of the few occasions in the year when all the “native” races took to the Padang for athletic competitions – mostly as objects of amusement and mockery for the European assemblage.8

However, as the local Straits Chinese community grew larger, more prosperous and financially secure in keeping with Singapore’s rising stature in global colonial-capitalism networks, it started to feel the need to assert itself socially. Numerous clubs sprang up in response, one of the most notable being a debating forum called the Celestial Reasoning Society in 1882.9 This need was personified by Lim Boon Keng and Song Ong Siang – both prominent members of the Straits Chinese community and Queen’s Scholars10 – who returned from their undergraduate studies in the United Kingdom in the early 1890s bursting with reformist zeal.

The duo, taking their sporting cues from the West rather than the East, exhorted the local Chinese to become more physically active through their new quarterly journal – the Straits Chinese Magazine (the two men were the editors). An article titled “Physical Religion” in the inaugural issue in March 1897 stressed the need for physical as well as mental fitness.

“If you do not wish to live a physically virtuous life, that is a healthy life, you are an immoral being,” it thundered. “Beauty of form, and physical strength and activity, as well as health, should be sought after and valued no less than beauty and power of mind.”11

Song led by example, being an avid tennis player who twice finished runner-up in the SCRC tennis championship in 1906 and 1909.12 And while there is scant evidence of Lim Boon Keng having played the game seriously, the good doctor was certainly an admirer. “Tennis might seem foolish to those who did not understand its science and art, but it was not so to experienced men,”13 he said during the presentation ceremony following the 1915 SCRC final.

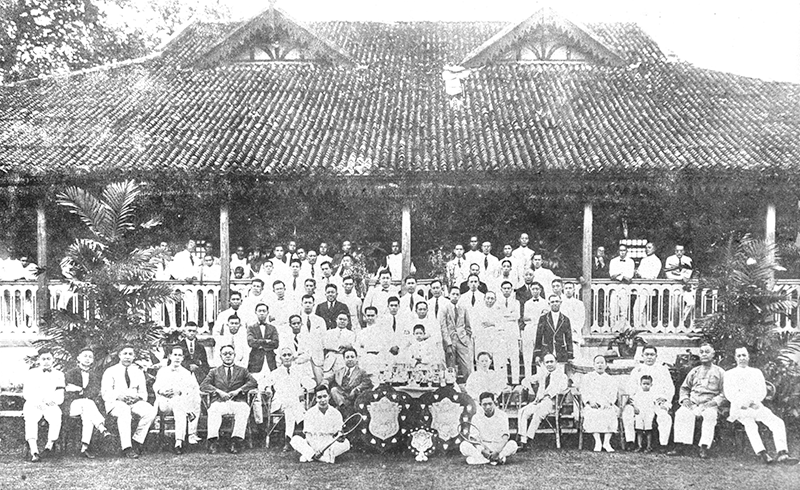

The SCRC had been founded in late 1884 by five prominent Straits merchants and had taken swiftly to imitating its Padang peers – the European Singapore Cricket Club (SCC) and the Eurasian Singapore Recreation Club (SRC).14 The SCRC’s first home was at an “open plain” below Pearl Hill but it was in the grander environs of Hong Lim Green where it moved to two years later that the club established itself as a prominent local institution. From the late 1880s, the green was home to regular cricket tournaments, a Chinese New Year Sports Day and an annual intra-club tennis tournament.15

Information on the club’s early years is sparse. We know that the first ever tennis tournament, held sometime between 1885 and 1890, was won by Koh Tiong Yan – a founder of the club – before another merchant called Chia Hood Teck dominated the scene for some time.16 During the first decade of the 20th century, Ong Tek Lim – a distinguished merchant who also served as municipal commissioner for the Central Ward – won the trophy five times.17

The SCRC championships continued apace during World War I. The club even expanded its reach, hosting Penang as well as travelling to the sister settlement to compete against its Chinese Recreation Club.18 However, it was only after 1918 that tennis in the Straits, especially Singapore, truly became a force to be reckoned with, thanks to men like Khoo Hooi Hye and Lim Bong Soo.

Tennis Ace Khoo Hooi Hye

The years following World War I saw an explosion in the popularity of tennis in Singapore and Malaya. Since the sport had no umbrella body and no sponsorship, the tennis calendar was a dizzying potpourri of competitions, exhibitions and tours largely dependent on the whims of colonial administrators and wealthy philanthropists.

In its most simplified form, the season could be described thus: each of the clubs – SCC, SRC, SCRC (there were others too) – had their own in-house competitions stretching back to the late 19th century. The next rung was the Singapore Championship, inaugurated in 1921 – variously called Singapore Lawn Tennis Championship, Singapore Tennis Tournament, Singapore Open – in which all Singapore residents, irrespective of nationality, were eligible to play. Variations of this structure had also sprung up across the peninsular territories.

The highest rung was occupied by the regional tournaments where the best players from across Singapore and Malaya competed against each other. With the differentiated nature of political administration under the British (three Straits Settlements territories and four Federated Malay States), there was an almost unlimited number of ways by which regions and players could be pitted against each other in a tournament format.

The most storied of these tournaments was the Malaya Cup, first organised in Singapore in 1921, in which the champions of the domestic tournament in Singapore, Penang, Melaka, Selangor, Perak and Negeri Sembilan faced off to determine the overall winner. It was in this milieu, with an unparalleled abundance of competitive tennis, that Khoo Hooi Hye came of age.

In the inaugural Malaya Cup, the 20-year-old Khoo, then playing for Penang, eased his way through the draw to make the final against Shunji Nakamura – an unknown Japanese resident in Singapore who had shocked all by lifting the Singapore Cup earlier that year. Both Khoo and Nakamura had beaten European opponents in the semi-finals of the peninsular competition. Of Nakamura’s victory in the semi-final, the Malaya Tribune mourned: “I think it a sad reflection on present-day tennis in Malaya that a player confining himself to such purely stonewalling tactics should be able to carry off the highest honours. Oliver [referring to E.N.W. Oliver, the champion of Selangor] has shown what I have said all along to be the game to beat him; and not only beat him but rout him.”19

In the other semi-final match, Khoo had easily disposed of a certain J.S. Johnstone of Negeri Sembilan. A correspondent for the Malaya Tribune wrote that “Johnstone was really a much better player than the score indicates. It was merely another case of steadiness overcoming brilliant but erratic methods. Johnstone’s service was swift and hard to return, but owing probably to lack of practice he could not always pull it off”20 (italics added for emphasis).

It was Nakamura who emerged victorious in the 1921 final. While Khoo did not win, the match was his stepping-stone to greatness. After moving to Singapore sometime in late 1922 or early 1923, Khoo won the Malaya Cup as its representative four times between 1923 and 1927 while holding his day job as an insurance agent of the Java Sea and Fire Insurance Co.21

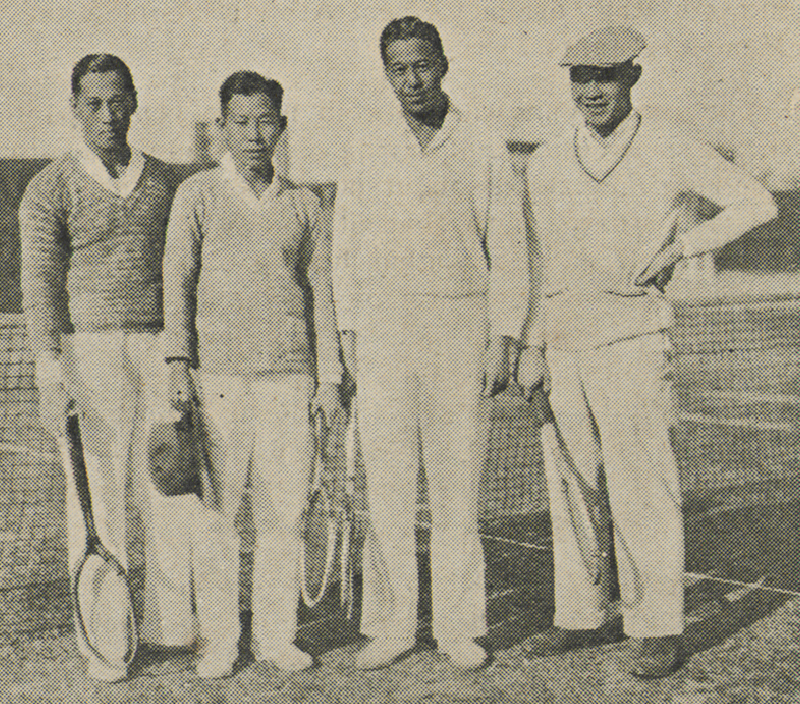

The biggest feathers in Khoo’s cap came in 1924. He became the first ever Malayan to play Wimbledon (he lost in the second round) and to participate in the Olympics in Paris, as part of a four-member Chinese contingent.22 Three years later, in 1927, Khoo won both the singles and doubles gold while representing China at the Shanghai Far Eastern Olympic Games (a precursor to the modern Asian Games).23

Apart from these tournaments, Khoo spent much of the 1920s winning accolades in Java, Manila and Hong Kong. There were also triumphs over the Calcutta and Thai singles champions and general acclaim that far from being merely steady, he was the most talented player the Straits had ever seen.24

Khoo’s success came at a time when sporting accomplishments were not only admired but feted among the Straits Chinese. Newspaper reports of some of his best matches ran into hundreds of words while dinner parties and concerts were thrown in his honour. Films capturing some of his matches were also shown in popular venues of the time.25

Lim Bong Soo’s Meteoric Rise

Lim Bong Soo’s rise to prominence in the mid-1920s added further glamour to the game as he and Khoo battled it out in individual competitions while representing Singapore in team tournaments across the region. Their first meaningful encounter was the 1926 Singapore Championship final in which “almost every game was marked with dazzling rallies”. Even though Lim lost to Khoo by two straight sets, a perceptive correspondent observed that “with a little more experience, however, Bong Soo should find his place somewhere near the top of the Malayan lawn tennis ladder”.26

Later in the year, the two met yet again, this time in the semi-final of the Malaya Cup and once again, the veteran Khoo managed to hold off his younger challenger in a close encounter.27 It would take two more years and that match on Hong Lim Green on 24 April 1929 for Lim to finally beat Khoo on the big stage.

In August 1929, the duo clashed again – this time at the SCC in the Malaya Cup final. In stark contrast to the earlier April match though, this one was an anti-climax. Lim, having played the singles and doubles semi-finals earlier that same day was forced to retire due to exhaustion, handing Khoo his fifth and final Malaya Cup.28

The year 1929 was one of the most memorable in Khoo’s celebrated career. Between the two contrasting clashes with Lim, he had played another match for the ages, on 20 June, in the Singapore Championship final against the Frenchman Paul Clerc.29

Clerc had had Khoo’s number in the previous year’s final and when he led 6-1, 5-1 within 25 minutes of the match, “it was eclipse”, as the Malaya Tribune vividly put it. But Khoo turned around this seemingly impossible situation to triumph 1-6, 8-6, 6-2. The same correspondent, nicknamed “Echo”, who had written so disparagingly about Khoo eight years ago was at it again. “Looking back on the match, it has to be conceded that Clerc ought to have won, and that he beat himself.”30

Such jibes notwithstanding, Khoo had overcome his April SCRC heartbreak by taking the two biggest trophies in the land – the Singapore Open and the Malaya Cup. These would be his final triumphs here.

In September 1929, Aw Boon Haw – who founded the Chinese ointment brand Tiger Balm – recognised that his salve and athletic endeavours made for natural allies. He decided to sponsor Singapore’s elite tennis and swimming athletes on a trip to the Far East where they competed in a medley of competitive and exhibition matches. Lim established himself as an all-Asian force by winning the Hong Kong Open before partnering Khoo in Shanghai to win almost every match there despite playing in such cold conditions that Lim’s “ear and lips split”.31

The Far East trip was a roaring commercial success with thousands of people watching the talented duo in action. Lim later wrote that “in their excitement, some of the spectators interfered by blocking and shouting during the progress of the play, so that Mr. C.G. Hoh, the Secretary of the Federation, had twice to stop the game temporarily to allow excited feelings to cool down”.32

The conclusion of this trip also brought the curtain down on Singapore tennis’ most storied era. In 1930, the Chinese government invited Khoo to represent China at that year’s Far Eastern Olympic Games in Tokyo – the same tournament where he had won gold for them in 1927. Khoo accepted and after the competition was over, he settled down in Shanghai. The paths of the two great friends and rivals would still cross occasionally – most notably when Lim beat Khoo in five enthralling sets in the final of the 1931 National Tennis Tournament organised by the Chinese National Amateur Athletic Foundation.33

With nobody to challenge him in Malaya now, Lim scaled new peaks. He racked up six straight Singapore Lawn Tennis championships between 1930 and 1935 to equal Khoo’s record (1923, 1925–29) and won the Malaya Cup three times in a row (1931–33), once again emulating his former rival who won it in 1923, 1925–27 and again in 1929.

In an interview with the Straits Times in 1983, Lim revealed that when he was at the height of his tennis career in 1933, a wealthy philanthropist – he refused to reveal who – had offered to sponsor his trip to Wimbledon.

“If I had gone, I might have made it to the semi-finals or even the final. Not in the first year, but maybe in the third or fourth. I was an all-rounder in tennis. I had no weakness,” he recalled wistfully.34

Back home though, the trophies kept coming and seizing on his unrivalled popularity, the storied English sports company Sykes released a line of rackets in his honour – the Lim Bong Soo Special – in 1936.35 Lim was then 33 years old but with no serious challenger on the horizon, it seemed like he was set to dominate the game for years to come.

Unfortunately, it was not to be. Tired of being unable to earn a living from the game he loved, Lim shocked the tennis world by going professional in May 1936 to take up a position as tennis coach at the Tanglin Club. (Going professional in those days meant earning a living from the sport whether as a coach or as a player.) He was instantly disqualified from defending both his Singapore and Malayan Cup titles (he had won the latter again in 1935 after missing out on the 1934 edition due to injury).

“We, as an Association are primarily concerned with the Amateur game, and we cannot encourage players to turn professional,” was the Singapore Lawn Tennis Association’s disapproving reaction. “But we can thank Mr Lim Bong Soo for the many pleasures which he has given us when we watched him play, and wish him the best of luck in his new venture.”36

The media was even more critical. “That professionalism should be creeping into Malayan sports is a thing the majority of us would hardly credit and it was particularly disturbing to hear that the finest tennis player in the country had decided to join the ranks of the paid last week,” sniffed the Straits Times sports correspondent. “Very often, however, one finds a person who is not quite top class a very excellent teacher. This is so at cricket and football and can also apply to lawn tennis.”37

It was a churlish farewell to a sporting great, though to give a sense of the times, Fred Perry, who became Britain’s greatest tennis star, turned professional that same year, also to widespread opprobrium.38

It would be 32 more years before the tennis world would allow, in 1968, those who played for prize money to compete with those who played as amateurs.

There was, however, a more poignant farewell in 1936. Khoo, who had spent the earlier part of the year playing in various exhibitions, died in July due to kidney complications. He was only 35 years old.39

Two days before Khoo’s death, N.S. Wise became the first ever European to lift the Singapore Lawn Tennis Championship.40 Between the two of them, Khoo and Lim had won 12 of 15 Singapore Championships and nine of the 15 Malaya Cups since both tournaments began in 1921. By keeping the Europeans at bay, they had shown the local Chinese that it was possible to not just play the colonial masters’ game but to beat them at it.

Unfortunately, Singapore tennis began a gradual decline after Khoo’s passing and Lim’s turn to professionalism, a decline exacerbated by the Second World War. “Where are the young and promising?” grumbled a tennis expert in 1951 when tennis had restarted in earnest.41 The writer was reacting to the fact that, quite incredibly, Lim, now 48 years of age and still playing tennis, had made it to the semi-finals of the Singapore Championships held that year.42

Tennis Champ Turned Golfer

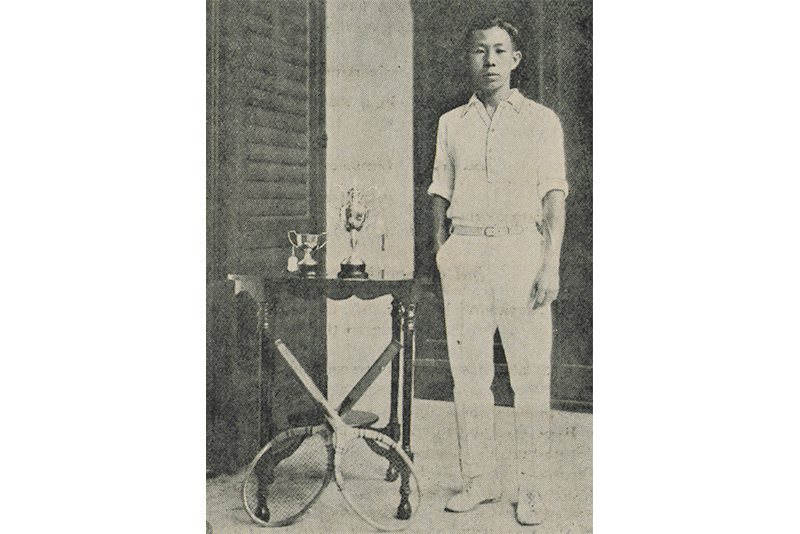

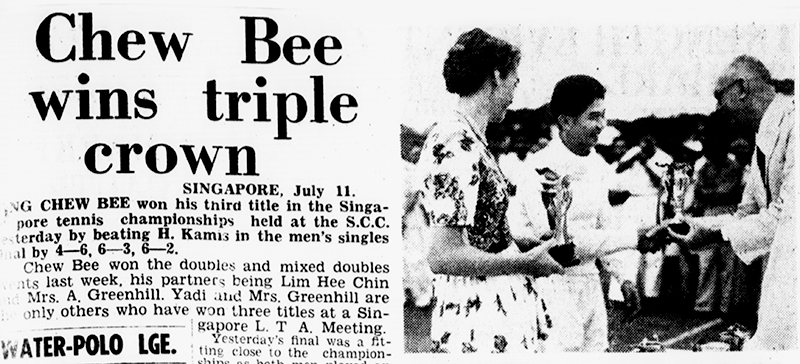

The game’s dying embers though, threw up a few final sparks. Ong Chew Bee, 26, became the first Singapore-born tennis player to play at Wimbledon’s hallowed lawns in 1951, losing in the first-round to Englishman G.D. Oakley in three hard-fought sets.43

Born in 1924, Ong had grown up when Khoo and Lim were at the peak of their fame and success but took up tennis at an unpropitious time in 1939, with the war looming over the horizon. Encouraged by his father, an eminent doctor, who built a tennis court at home, Ong persevered through the lack of tournaments and even a shortage of tennis balls to emerge on the other side of the war as one of the region’s most accomplished players. By 1950, Ong was striding across Malayan courts like a colossus in the mould of pre-war heroes Khoo and Lim. That year, Ong won the singles and doubles tournaments at both the Singapore Championship and the Malaya Cup. For good measure, he won the former’s mixed doubles too.44

Ong’s father rewarded him for these exploits with a trip to Wimbledon in 1951. While he was beaten in the first round, Ong would not lose to a Malayan player for the rest of the decade. By the time he hung up his racket, Ong had won eight Singapore Championships (1950, 1952–58), three Malaya Cups (1950, 1954–55) and travelled to Ceylon, the Philippines and India as a member of the Malayan Davis Cup team. There was an astonishing post-script as well. After retiring from tennis, the right-handed Ong took up golf – left-handed – and emerged as one of Singapore’s most successful amateur golfers. He was also part of the team that won the 1967 Putra Cup.45

Meanwhile, as the 20th century drew to a close, Singapore tennis had some sporadic success. The men’s team won silver in the 1981 Southeast Asian Games and two years later, national women’s champion Lim Phi Lan won bronze in the same competition.46 But when Lim Bong Soo died in 1992 at the age of 92 (birth dates in the early 20th century were unreliable so this may not be precise; for instance, a 1951 report refers to Lim as 48 years old, indicating that he was born in 1902 or 1903), independent Singapore had yet to send a player to Wimbledon, or indeed to any of the other Grand Slams.

In 2019, Singapore-born Astra Sharma did make it into the main draw of all four Grand Slams but she had moved to Australia in 2005 when she was 10 and played in these tournaments as an Australian citizen.47

Sadly, the tantalising hopes of Singapore as a tennis power created by the spellbinding duo of Khoo Hooi Hye and Lim Bong Soo and then, briefly, by Ong Chew Bee, have proven to be elusive thus far.

Abhishek Mehrotra is a researcher and writer whose interests include media and society in colonial Singapore, urban toponymy and post-independence India. He is working on his first book – a biography of T.N. Seshan, one of India’s most prominent bureaucrats. The book, commissioned by HarperCollins, is slated for release in 2024. Abhishek is a former Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow (2021–2022).

Abhishek Mehrotra is a researcher and writer whose interests include media and society in colonial Singapore, urban toponymy and post-independence India. He is working on his first book – a biography of T.N. Seshan, one of India’s most prominent bureaucrats. The book, commissioned by HarperCollins, is slated for release in 2024. Abhishek is a former Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow (2021–2022).NOTES

-

“Hooi Hye Beaten,” Malaya Tribune, 25 April 1929, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Hooi Hye Beaten.” ↩

-

“‘Our Day’ Tennis,” Straits Echo, 18 September 1917, 3; “Golden Jubilee of Straits Chinese Recreation Club,” Malaya Tribune, 13 May 1935, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Khoo Hooi Hye’s Last Year,” Straits Times, 20 May 1930, 15. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Hooi Hye Beaten.” ↩

-

“Hooi Hye Beaten.” ↩

-

“Hooi Hye Beaten.” ↩

-

Nicholas G. Aplin and Quek Jin Jong, “Celestials in Touch: The Development of Sport and Exercise in Colonial Singapore,” The International Journal of the History of Sport 19, no. 2–3 (2002): 68, 72, NIE Digital Repository, https://repository.nie.edu.sg/handle/10497/19780. ↩

-

The Celestial Reasoning Association was considered the first debating society formed by the Straits Chinese and the earliest literary society for educated Chinese. See Bonny Tan, “Celestial Reasoning Association,” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published September 2020. ↩

-

Lim Boon Keng in 1893; Song Ong Siang in 1894. ↩

-

T.B.G., “Physical Religion,” Straits Chinese Magazine: A Quarterly Journal of Oriental and Occidental Culture 1, no.1 (March 1897): 9. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RRARE 959.5 STR) ↩

-

Song Ong Siang, One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1984), 247. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 SON-[HIS]) ↩

-

“Sporting Intelligence,” Malaya Tribune, 25 November 1915, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Singapore saw a sports club boom in the mid-1880s. The Singapore Recreation Club was formed in 1883, the Ladies Lawn Tennis Club in November 1884 and the Straits Chinese Recreation Club a month later. ↩

-

Song, One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore, 216, 288. ↩

-

Song, One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore, 216. ↩

-

Apart from being an excellent tennis player, Ong Tek Lim was also a municipal commissioner and a Justice of the Peace. He was only 36 years old when he died of dysentery in 1912. For details, see Song, One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore, 481. ↩

-

“Lawn Tennis,” Malaya Tribune, 9 September 1921, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Lawn Tennis.” ↩

-

“Nakamura’s Fine Record,” Malaya Tribune, 18 July 1922, 8; “Untitled,” Straits Times, 5 September 1923, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Lawn Tennis,” Malayan Saturday Post, 5 April 1924, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Far Eastern Olympiad,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (Weekly), 7 September 1927, 151. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Hooi Hye Beaten.” ↩

-

“Public Amusements,” Straits Times, 27 July 1923, 10; “Untitled,” Straits Times, 5 September 1923, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Lawn Tennis,” Malaya Tribune, 8 January 1927, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Malayan Lawn Tennis Championships,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 3 August 1927, 20. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Malayan Meeting,” Malaya Tribune, 6 August 1929, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Hooi Hye Champion,” Malaya Tribune, 21 June 1929, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Hooi Hye Champion.” For the earlier 1921 report by the same correspondent, see “Lawn Tennis.” ↩

-

Lim Bong Soo, “Some Impressions of My Trip to China,” in Straits Chinese Annual, 1930, ed. Song Ong Siang (Singapore: Kwa Siew Tee, Ho Hong Bank, 1930), 97. (From BookSG) ↩

-

Lim, “Some Impressions of My Trip to China,” 95. ↩

-

“Chinese National Champion. Lim Bong Soo’s Success in Shanghai,” Straits Budget, 5 November 1931, 31. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Leonard King, “To Serve, with Love,” Straits Times, 17 April 1983, 28. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Walton Morais, “Rolling Back the Years with a Legend,” Business Times, 8 November 1986, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Singapore Lawn Tennis Association,” Malaya Tribune, 30 January 1937, 24. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Is Bong Soo Wise to Turn Professional?,” Straits Times, 10 May 1936, 27. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Fred Perry To Be In Action Again,” Malaya Tribune, 3 May 1948, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Death of Khoo Hooi Hye in Penang,” Malaya Tribune, 27 July 1936, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“N.S. Wise the First European to Win Singapore Title,” Straits Times, 25 July 1925, 14. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Big Moments and the New Stars,” Straits Times, 31 December 1951, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

It is unclear how Lim Bong Soo, as a professional, was allowed to compete again. One possible explanation is that he had retired from coaching by then and was thus no longer considered a professional. ↩

-

“Ong Chew Bee Disappoints,” Singapore Free Press, 26 June 1951, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Teoh Eng Tat, “After 11 Years the Zest Is Fading, Says Chew Bee,” The Straits Times, 20 July 1960, 15. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lester Wong, “Obituary: 1950s Tennis Kingpin Ong Chew Bee, Later a National Golfer, Lived the Sporting Life,” Straits Times, 24 March 2018, https://www.straitstimes.com/sport/obituary-1950s-tennis-kingpin-ong-chew-bee-later-a-national-golfer-lived-the-sporting-life. ↩

-

Tan Hai Chuang, “Tennis, Anyone?,” Straits Times, 13 May 2000, 81. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Astra Sharma,” WTA Tour, accessed 22 October 2022, https://www.wtatennis.com/players/319696/astra-sharma#grandslams. ↩