Remembering Punggol’s Kampong Wak Sumang and the Man Who Made It Happen

Kampong Wak Sumang, one of Singapore’s earliest fishing villages, was purportedly founded by a warrior-diplomat whose musical abilities landed him in trouble.

By Hannah Yeo

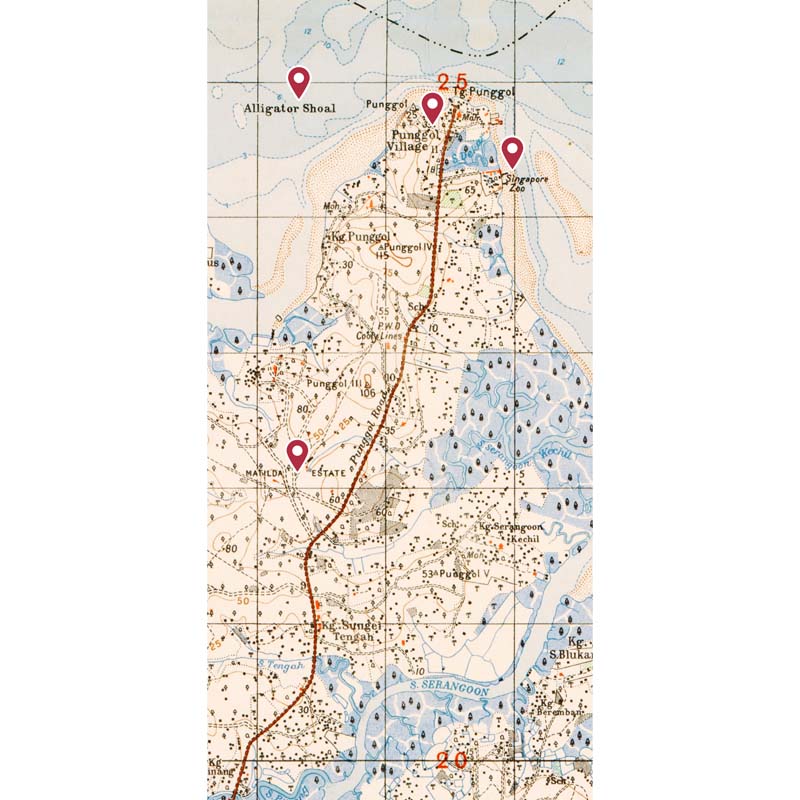

As you walk around Punggol today, you may encounter the name “Sumang”. Sumang Walk runs along the eastern bank of the Punggol River, near the Jewel Bridge. The southern end of Sumang Walk terminates at Sumang Lane. Meanwhile, Sumang LRT station, which is nearby Waterway Residences, lies along Punggol Way between Nibong and Soo Teck stations.

The name Sumang belongs to the man who founded Kampong Wak Sumang, also known as Kampong Punggol – one of Singapore’s earliest kampongs.1 This kampong was situated at Punggol Point, a 10-minute cycle from the current Sumang neighbourhood.

For over 100 years, the growth of Kampong Wak Sumang reflected changes in the Punggol Point community, until its residents relocated in the 1980s to make way for today’s public housing estate.2 Although no physical traces of the kampong remain, fragments of its story can be pieced together from books, oral history interviews, newspaper reports and artefacts in the collections of the National Library and the National Archives of Singapore.

Sumang, Who?

“Her husband was named Che’ Soman, who hailed from Daik. He was talented in playing the violin, and was also humorous and cheerful. Some also said that he was a warrior.”3

Like many indigenous communities, Wak Sumang’s history has been passed down primarily by word of mouth. While this sometimes makes it difficult to separate fact from fiction, it invites us to shift our focus to the values and morals being disseminated through the oral tradition and surviving stories.

Wak Sumang (also known as Wah Soomang, Wah Sumang, Tok Sumang and Che Soman) is believed to have landed on Punggol Beach in the mid-1800s. He came from the Riau Islands, likely Daik. While he is generally said to have been Javanese, at least one source says he was Bugis.4

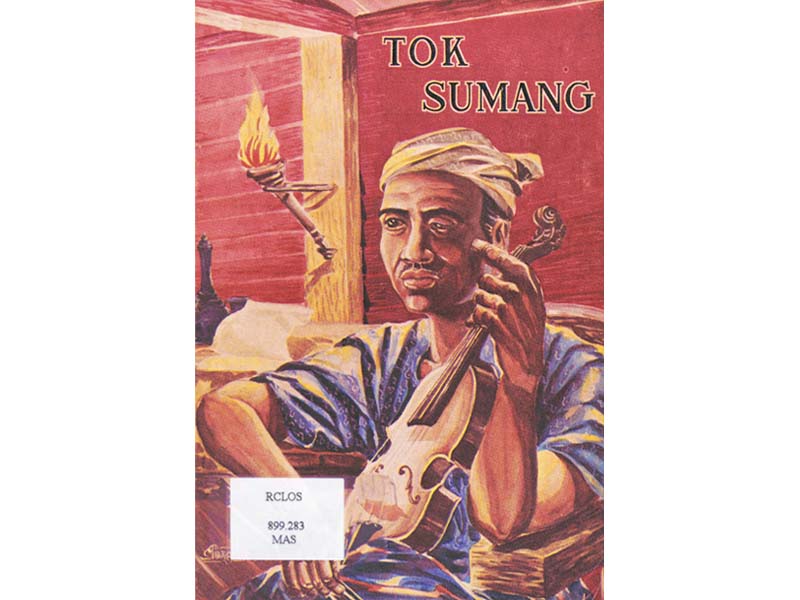

The Malay literary pioneer Muhammad Ariff Ahmad (writing under the pen name Mastomo) wrote a story of Sumang’s life titled Tok Sumang, which was published in 1957. The work details the exploits of Sumang in the court of Lingga Sultan Mahmud Muzaffar Shah (r. 1841–57) during the time of the Pahang Civil War (1857–63).5 Muhammad Ariff based the book on stories he had heard from descendants of Wak Sumang while he was teaching at Sekolah Melayu Ponggol (Ponggol Malay School).6

In Muhammad Ariff’s account, Sumang is described as a talented musician. “It is surely fictitious if we say that the birds stopped flying when they heard Tok Sumang playing the violin. However, if a lady hears the melodious notes of Tok Sumang’s violin and is not halted while working, it can be said that she is not a lady,” he wrote.7 Sumang’s job in the court was to entertain the sultan and those around him. In addition, he was known as a healer and wiseman.8

Sumang’s skill as a musician, unfortunately, led to a tricky situation because his violin playing enchanted the sultan’s daughter, who asked to marry him.9 Sumang, who was already married with three sons, fled the Lingga court with his family to avoid a scandal. However, his great-grandson Jusoh Ahmad told the Berita Minggu newspaper in 1983 that it was the sultan’s concubine, and not the daughter, who wanted to marry Sumang. According to Jusoh, “Wah Soomang was unable to return her affections, however, as he was afraid that this would anger the king. And once again, he journeyed to another land to start a new life”.10

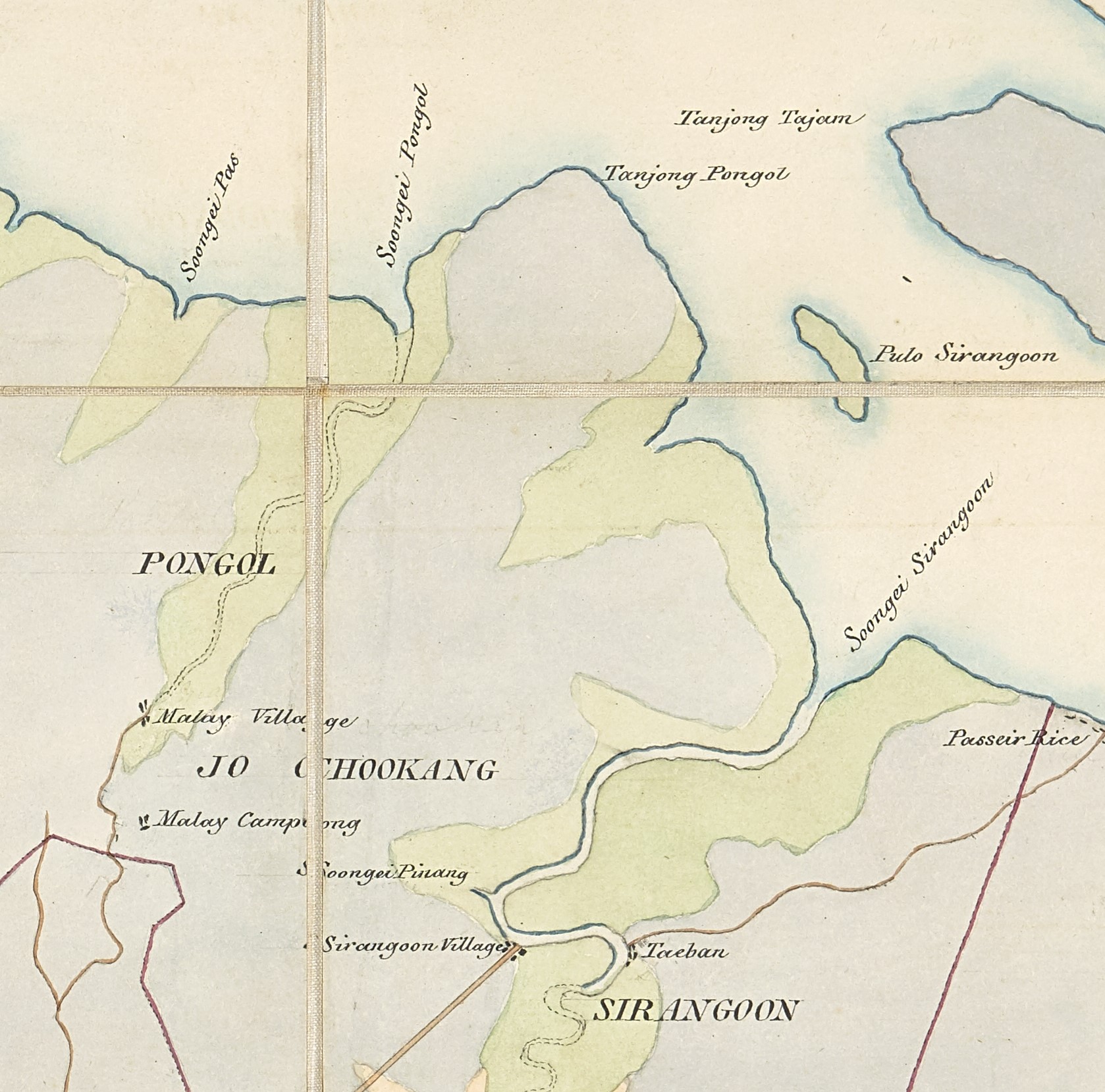

While Mastomo’s Tok Sumang suggests that Kampong Wak Sumang was established in the 1850s or 1860s, an 1852 map of Singapore, based on surveys conducted between 1841 and 1845, shows a Malay community around Punggol Point from as early as the 1840s.11

Sumang and his family’s long journey to Punggol included stopovers at other islands. Some accounts say he helped set up another village, Kampong Pahang, on Pulau Tekong before arriving in Punggol.12 Besides Punggol, some of Sumang’s relatives settled in Kampong Pos in Seletar. Sumang would later have more children and grow his village in Punggol.13

When Sumang died in the late 1800s, he left behind a huge estate for his descendants in Punggol, comprising fruit plantations and at least nine houses.14 As much of Punggol has been reclaimed, it is difficult to determine the exact location of this old kampong, but we know from a 1986 Berita Minggu newspaper report that Sumang’s estate comprised two land parcels, Lot 23 and 24.15 These added up to 10.27 acres (4.16 hectares), almost the size of the Padang.16

In addition to setting up the kampong, Sumang is also believed to have dug a five-metre-deep well in the kampong. It was said to never run dry and to contain healing properties.17 Haji Mohammed Amin Abdul Wahab, a teacher and resident in the kampong, told the Straits Times in 1995 that the villagers believed that the well could cure children of fever and epileptic fits. “They would bring their children to bathe with the well water before dawn and they were cured,” he said.18

Wak Sumang’s Legacy

“The life of a tree brings fruit, the life of a person brings benefit.”19

After Sumang’s death, his descendants built on his legacy. An early example can be seen in the construction of the old Punggol Road, which was originally a sandy track for bullock carts (the road is a part of Hougang Avenue 8 and Hougang Avenue 10 today).20

According to Mastomo’s Tok Sumang, one day in 1890, a government official arrived in the village asking to build a road through Sumang’s estate, and he was met by Long Amat, Sumang’s eldest son. His brothers, Che’ Mamat and Si Kemidin, were keen to accept the government’s generous offer of compensation. However, Long Amat encouraged his brothers to take a long-term view with a quote from their father: “Hidup pohon biar berbuah, hidup manusia biar berfaedah!” (“The life of a tree brings fruit, the life of a person brings benefit!”).

Instead of accepting the government payout, Long Amat proposed that they ask the government to guarantee that their land would not be taxed so that their descendants could live there freely for many generations to come.21 This arrangement would prevail for almost 100 years before Sumang’s descendants traded kampong life for high-rise living in the 1980s.22

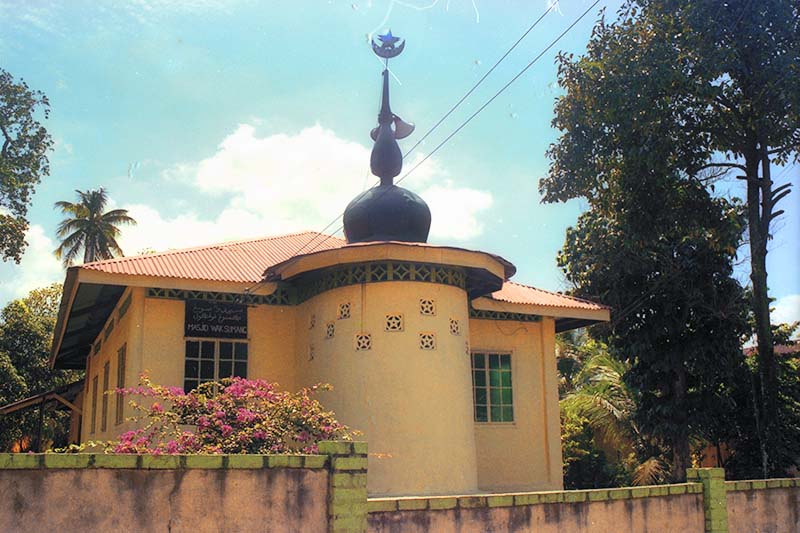

Apart from the kampong, the former Masjid Wak Sumang at Track 26 of the old Punggol Road also bore Sumang’s name. The mosque started out as a shrine by the sea, which Sumang erected when he arrived in Punggol.23 Over time, as the shrine deteriorated, it was demolished and Masjid Wak Sumang was built with the help of the community after World War II. Reginald Schooling, a retired foreman with the Royal Air Force who had lived in Punggol since 1948, told the Straits Times in 1984 that everyone pitched in to help. “When the villagers needed a mosque we all contributed what we could. I donated $200. Some gave bricks, some gave cement and wood, while others contributed an hour or two of their time.”24

Masjid Wak Sumang served as an epicentre of religious activity as well as a meeting point for villagers and visiting political heads who wished to meet the people of the kampong.25 Interestingly, one such visitor was Richard Nixon, who was then vice-president of the United States. He visited Punggol Point as the first stop in a tour of rural areas during his 1953 visit to Singapore.26

Sumang and his wife Gobek were buried near the grounds of Masjid Wak Sumang.27 When the mosque was demolished to make way for redevelopment in 1995, the couple’s remains were exhumed and reburied at Jalan Bahar Muslim Cemetery.28 Some of the items that belonged to the mosque – such as drums, prayer mats, prayer schedules, the sermon stick and mosque pulpit – were taken into the repositories of the National Museum of Singapore and the Asian Civilisations Museum.29 Staff from the National Archives of Singapore also took photographs of the area and conducted oral history interviews. One of these interviews was with Awang Osman (1906–90), the village penghulu (headman or chief).30

Changing Communities

Awang Osman was Kampong Wak Sumang’s headman from 1932 until its demolition in 1985.31 His account of the kampong’s history is captured in 800 minutes of oral history interviews with the National Archives of Singapore, recorded over 30 reels between August 1984 and December 1985. Wak Sumang was Awang Osman’s maternal great-grandfather.32

In his interviews, Awang Osman recalled the dark days that followed after Singapore fell to the Japanese in February 1942. He and everyone else in Kampong Wak Sumang fled inland. “Of course I ran. The white [British] people told me, don’t stay here, you must flee. So I started running… there wasn’t a single person who remained in the kampong.”33

After the Japanese invaded, they massacred thousands in an effort to purge anti-Japanese elements from the Chinese community (now known as Operation Sook Ching34). Punggol Beach was one of the execution sites. Awang Osman had not witnessed the killings, but he saw the aftermath. “When I returned [to Punggol], there were many Chinese who had been killed, floating in the sea. They had been shot by the Japanese. All in all there were maybe 500 [to] 600 people. Some were tied up with ropes, others impaled by barbed wire,” he recounted.35

When the Japanese Occupation ended, residents rebuilt Kampong Wak Sumang with the little compensation they received from the British authorities. This included restoring Masjid Wak Sumang and other community spaces.

A new phase of Kampong Sumang’s history began after the kampong took in refugees from three villages in Johor – Ayer Biru, Pasir Merah and Pulau Tukang – during the Japanese Occupation and the Malayan Emergency (1948–60).36 The Johoreans settled inland and were called orang darat (land people), while the original inhabitants and descendants of Wak Sumang referred to themselves as orang laut (sea people).37 Their nickname notwithstanding, the Johoreans actually spent most of their time out at sea. Being skilled fishermen, their arrival kick-started the kupang (mussel) trade in the kampong. Shelling was done by hand and it took around six to eight people three hours to shell a full sampan (a small boat with a flat bottom) load of mussels.38

“Whenever you see a lot of smoke coming out from my house, it means good business. I use pieces of wooden planks from a nearby dumping ground as firewood – that’s why it’s so smoky,” mussel farmer Jantan Rani told the Straits Times in 1984. Mussel farmers could earn double what they used to make as fishermen in a day. However, the widespread use of fire had its dangers. In 1981, Jantan Rani’s house caught fire and burned down. “I returned home to find my wife crying and my house in ashes. We lost everything, furniture, refrigerator, television and all.”39

As the community grew, the villagers in Kampong Wak Sumang decided to build a Malay School – Sekolah Melayu Ponggol – to educate the younger generations. It opened in 1955 with funds raised through the Rotary Club and other private donors.40 In 1963, the school was taken over by the government and moved to Track 13.41

Developing Punggol

In the 1960s, Kampong Wak Sumang welcomed piped water, electricity, paved roads and drainage systems. Punggol Point was also becoming well known for its open-air seafood restaurants and boatels (boat storage and water sports centres). Besides providing docking facilities for pleasure boats when not in use, these boatels also rented out boats for water skiing, fishing and sightseeing activities. People would come from all over Singapore to soak in the sea breeze, enjoy delicious seafood and take part in water sports. Punggol Point became a popular recreational spot for locals and tourists.42

The residents of Kampong Wak Sumang were part of the thriving scene. Some like Awang Abdullah, whose nickname was Awang Pendek, ran a boatel business. Others sold their fishing catch to seaside restaurants and hotels and also at nearby markets in Kangkar and Punggol.43

The idyllic kampong life, however, would ultimately come to an end. In 1983, the government announced that it would be undertaking a reclamation project for future housing needs in Punggol. Some 277 hectares of land would be reclaimed off the Punggol coastline over the next three years at a cost of $136 million.44 Residents of Kampong Wak Sumang, as well as Punggol Point’s famous seafood restaurants and boatels, were asked to vacate their premises by 1986.45

Not everyone was ready to part ways with the kampong. After giving up his boatel business and moving to Hougang, former headman Awang Osman made it a point to return to Kampong Wak Sumang every day. In an interview with Berita Minggu in 1987 – when he was already 100 years old – Awang Osman vowed to continue visiting the kampong as long as his body was able and the site had not been developed into a housing estate. Echoing the wisdom of his great-grandfather, Awang Osman summed up the villagers’ sentiments with the Malay proverb, “Tempat jatuh lagi dikenang, inikan pula tempat bermain”. While the adage literally means “where we stumbled, we also rejoiced”, it conveys that it was not easy for people to forget the place that had been their home for decades.46

Although they had been resettled, some continued to rely on the sea for a living. Awang Atan, like many in his community, continued to work as a fisherman. In 1987, he told Berita Minggu that he could earn $300 a month by selling fish, crabs and mussels to nearby kelong (an offshore platform made of wood for fishing) and the Punggol Fish Market. “The sea is my flesh and blood,” he said “[and] I have been happy with this way of life for generations”.47

In the same news report, Mohamed Baba revealed that he was still able to make a decent living from the sea. “I can get 50 kilos of mussels daily and earn $100 from the kelongs on a good day,” he said. “After deducting fuel and rental for the motorboat, and also after paying the helpers, my net profit can be $30.”48

Those who owned boatels stayed behind to faithfully watch over their clients’ boats. Almost 10 years after most of the villagers had left, Jimat Awang of Awang Boat Sheds and Zainal Jantan of Zainal Water-ski Centre were still looking after the boats under their care.

“My brother, my brother-in-law and I will be staying behind to take turns to keep an eye on the boats,” said Jimat Awang when he was interviewed by the New Paper in September 1994. This was even though his main office building, the two huts where the family slept in, and his store had been torn down. Zainal Jantan said that “he and a few friends would also be watching over his 40 to 50 boats” and “sleep in a small hut that had not been demolished, but the rest of his family would be returning to their Hougang flat”.49

Revisiting Punggol

Although Kampong Wak Sumang no longer exists today, its legacy lives on in the stories of the people who once called it home.

The National Library Board (NLB) is showcasing some of these stories at Singaporium – a permanent exhibition space located at level four of the new Punggol Regional Library – to bring its heritage collections closer to the community. The inaugural exhibition, “Punggol Stories”, features the Tok Sumang book by Muhammad Ariff Ahmad as well as memories collected from former Punggol residents, including those who used to live in Kampong Wak Sumang.

To make the stories of Wak Sumang and his contributions more accessible to the wider community, Ahmad Ubaidillah – whose mother Rohaida Ismail is a descendant of Wak Sumang and grew up in Kampong Wak Sumang – has translated Tok Sumang into English (read the original Malay digitised text on BookSG, while the English translated version can be accessed here). Ahmad Ubaidillah was inspired to translate the book after hearing his mother’s stories of her kampong and Wak Sumang.

“Punggol Stories” is part of NLB’s efforts to grow #SingaporeStorytellers and there are many more stories waiting to be told. Members of the public who wish to share their stories and memories of Punggol are encouraged to do so via social media using the hashtag #PunggolStories.

The name “Poongul” appears in an 1820s map of Singapore. While it is highly unlikely that Wak Sumang alone gave Punggol its name, stories about his encounters with punggur continue to be repeated. The Malay word punggur refers to dead wood and comes from the words pokok (tree) and gugur (to fall).

Some say that a felled trunk of a tree was in Punggol before the arrival of Sumang, while others claim that a broken tree branch fell on Sumang’s house. Other stories say that Sumang saw a punggur floating in Punggol River, inspiring him to name his kampong and the river after it.

A funny version of the origins of the name “Ponggol” in Tok Sumang involves an intercultural misunderstanding. Apparently, Sumang was chopping down the trunk (punggur) of a rumbia tree (also called sago tree) when a white man and his Indian interpreter came to visit.

Tok Sumang was unable to comprehend what the interpreter explained to the white man, but he heard the white man repeatedly saying, “Ponggor… Ponggol…”

Awang Bin Osman, oral history interview by Mohd Yussoff Ahmad, 11 August 1984, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 3 of 30, 31–33, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000319).

Mastomo, Tok Sumang (Singapore: Geliga Limited, 1957), 33. (From BookSG)

Mohd Amin Bin Abdul Wahab (Haji), oral history interview by Ruzita Zaki, 23 January 1995, MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 1 of 44, 25.50–26.22, 28.30–29.40, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 001597).

Rosli A Razak, “Evolusi Sejarah Punggol daripada sebuah Kampung Nelayan kepada Bandar Moden Mesra Alam,” Berita, 24 February 2023, https://berita.mediacorp.sg/singapura/evolusi-sejarah-punggol-daripada-sebuah-kampung-nelayan-kepada-bandar-moden-mesra-alam-735266.

Sarafian Salleh, correspondence, April 2023.

The National Archives, UK, Plan of the Island of Singapore Including the New British Settlements and Adjacent Islands, c. 1820, map. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. D2019_000020_TNA)

“What’s in a Name,” Straits Times, 14 August 1990, 7. (From NewspaperSG)

Hannah Yeo is a Curator with the National Library, Singapore, and curated the “Punggol Stories” trail at Punggol Regional Library.

Hannah Yeo is a Curator with the National Library, Singapore, and curated the “Punggol Stories” trail at Punggol Regional Library.Notes

-

Kamsiah Abdullah, et al., eds., Malay Heritage of Singapore (Singapore: Suntree Media in Association with Malay Heritage Foundation, 2010), 91. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 959.570049928 MAL-[HIS]) ↩

-

Saini Salleh, “Sungai Wak Sumang Terus Menjadi Tempat Pertemuan,” Berita Harian, 13 December 1987, 3 (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

This is the English translation by Ahmad Ubaidillah, a descendant of Wak Sumang. For the original Malay version, see Mastomo, Tok Sumang (Singapore: Geliga Limited, 1957), 4. (From BookSG; accession no. B29234707A) ↩

-

“What’s in a Name,” Straits Times, 14 August 1990, 7 (From Newslink via NLB’s eResources website); Saini Salleh, “Sungai Wak Sumang Terus Menjadi Tempat Pertemuan,” Berita Harian, 13 December 1987, 3 (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Pahang Civil War Breaks out,” in HistorySG, National Library Board Singapore. Article published 2014. ↩

-

Mohd Raman Daud, “Tempa Nama Lewat Novelet,” Berita Harian, 28 April 2014, 7 (From Newslink via NLB’s eResources website); Mastomo, Tok Sumang, 4–5. ↩

-

This is the English translation by Ahmad Ubaidillah. For the original Malay version, see Mastomo, Tok Sumang, 6. ↩

-

Mastomo, Tok Sumang, 6, 10, 24. ↩

-

Mastomo, Tok Sumang, 18. ↩

-

Mastomo’s Tok Sumang is most closely matched by the account of Jusoh Ahmad, who was the son of Ahmad, son of Lambak, son of Wak Sumang and Kopek. See Mohd Maidin, “Penggesek Biola Yg Masyhor Buka Kg Wak Sumang,” Berita Minggu, 13 March 1983, 3. (From NewspaperSG) [English translation by Hannah Yeo and Diyanah Kamarudin.] ↩

-

The National Archives, UK, Map of Singapore Island, and Its Dependencies, 1852, map. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. SP006879); Mok Ly Yng, correspondence, March 2023. ↩

-

Mohd Amin Bin Abdul Wahab (Haji), oral history interview by Ruzita Zaki, 23 January 1995, MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 1 of 44, 15.50–24.33, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 001597); Mastomo, Tok Sumang, 23. ↩

-

Awang Bin Osman, oral history interview by Mohd Yussoff Ahmad, 26 December 1985, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 27 of 30, 340, 347, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000319). Awang Osman’s maternal grandfather was a son of Wak Sumang. ↩

-

Awang Bin Osman, interview, Reel/Disc 27 of 30, 344; Mohd Amin Bin Abdul Wahab (Haji), interview, Reel/Disc 1 of 44, 9.35–11.58. ↩

-

Cucu2 Wak Sumang Diberi Flat”, Berita Minggu, 30 March 1986, 2 (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Mok Ly Yng, correspondence, January 2023; Joanna Tan, “The Padang,” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published March 2021. ↩

-

Saini Salleh, “Perigi Tua Wak Sumang”, Berita Harian, 8 January 1995, 3 (From Newslink via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

“A Well That Never Runs Dry,” Straits Times, 11 January 1995, 11 (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

This is the English translation by Ahmad Ubaidillah. For the original Malay version, see Mastomo, Tok Sumang, 35. ↩

-

“Municipal Commissioners,” Straits Times, 1 April 1876, 1; “The Municipality,” Straits Times Weekly Issue, 5 January 1884, 7 (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Mastomo, Tok Sumang, 34–37. ↩

-

Saini Salleh, “Warisan Masjid Diabadi,” Berita Harian, 5 January 1995, 3 (From Newslink via NLB’s eResources website); Mohd Maidin, “Penggesek Biola Yg Masyhor Buka Kg Wak Sumang.” ↩

-

“The Changing Face of Punggol,” Straits Times, 16 January 1984, 28. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Sarafian Salleh, correspondence, March 2023. ↩

-

“Mr. Nixon Tours Rural Areas,” Indian Daily Mail, 26 October 1953, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Mohd Maidin, “Penggesek Biola Yg Masyhor Buka Kg Wak Sumang; Rohaida Ismail, correspondence, April 2023. ↩

-

Rohaida Ismail, correspondence, April 2023. ↩

-

Tuminah Sapawi, “Quiet Fishing Village in Punggol to Go Down in History,” Straits Times, 19 January 1995, 26 (From NewspaperSG); “A Well That Never Runs Dry”; Saini Salleh, “Khazanah Wak Sumang Berpindah Sudah”, Berita Harian, 8 January 1995, 2. (From Newslink via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Awang Bin Osman, oral history interview by Mohd Yussoff Ahmad, 9 August 1984, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 1 of 30, 1, 6–7, 9. [Awang Osman’s father, Osman Bujang, was a Bugis born on Pulau Ubin. He moved first to Kampong Pos in Seletar and then to Kampong Wak Sumang when he married Kendah Kaman, a granddaughter of Wak Sumang. Both Awang Osman and his father were fishermen and also builders of kelong (an offshore platform built predominantly with wood and used for fishing purposes).] ↩

-

Awang Bin Osman, interview, Reel/Disc 1 of 30, biographical information; Awang Bin Osman, oral history interview by Mohd Yussoff Ahmad, 15 August 1984, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 9 of 30, 118–119. ↩

-

Awang Bin Osman, oral history interview by Mohd Yussoff Ahmad, 11 August 1984, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 3 of 30, 28–30; Mohd Amin bin Abdul Wahab (Haji), interview Reel/Disc 1 of 44, 16.12–16.25. ↩

-

Awang Bin Osman, oral history interview by Mohd Yussoff Ahmad, 15 August 1984, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 10 of 30, 134. [English translation by Hannah Yeo and Diyanah Kamarudin.] ↩

-

Stephanie Ho, “Operation Sook Ching,” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published 17 June 2013. ↩

-

Awang Bin Osman, Reel/Disc 10 of 30, 134. [English translation by Hannah Yeo and Diyanah Kamarudin.] ↩

-

Awang Bin Osman, interview, Reel/Disc 3 of 30, 26; Awang Bin Osman, oral history interview by Mohd Yussoff Ahmad, 19 August 1984, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 16 of 30, 209; Awang Bin Osman, Reel/Disc 27 of 30, 344. ↩

-

Rohaida Ismail, correspondence, July 2022. ↩

-

Yeo Kim Seng, “Farmer Flexes Muscles for Mussel Business,” Straits Times, 18 September 1984, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Awang Bin Osman, oral history interview by Mohd Yussoff Ahmad, 19 August 1984, Reel/Disc 17 of 30, 221–222; Mohd Amin Bin Abdul Wahab (Haji), oral history interview by Ruzita Zaki, 27 February 1995, MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 16 of 44, 0.16–0.20. ↩

-

Saini Salleh, “Perigi Tua Wak Sumang”, Berita Harian, 8 January 1995, 3 (From Newslink via NLB’s eResources website); Awang Bin Osman, interview, Reel/Disc 17 of 30, 219–220. ↩

-

Gerry De Silva, “An Urban Punggol Tries to Preserve Part of Its Past,” Straits Times, 14 June 1988, 19. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Emilia Azman and Hajjah Saniah Othaman, correspondence, April 2023. ↩

-

“Land Reclamation off Punggol,” Straits Times, 5 March 1983, 17; “Plan for Punggol Park on Reclaimed Land,” Straits Times, 15 July 1983, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Yeo, “The Last Days of a Fishing Village”; Gillian Pow Chong, “Teh to Decide on Future of Punggol,” Straits Times, 12 November 1985, 1; “Big Boatel Gets Notice to Quit,” Straits Times, 19 September 1986, 16. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Saadon Ismail, “Tempat Jatuh Lagi Dikenang…,” Berita Minggu, 1 February 1987, 3 (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Saini Salleh, “Sungai Wak Sumang Terus Menjadi Tempat Pertemuan.” [English translation by Hannah Yeo and Diyanah Kamarudin.] ↩

-

Saini Salleh, “Sungai Wak Sumang Terus Menjadi Tempat Pertemuan.” [English translation by Hannah Yeo and Diyanah Kamarudin.] ↩

-

“Keeping Eye on Boats,” New Paper, 8 September 1994, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩