32 Binjai Park: The Modernist Home of an Architect

The house that Lee Kip Lin built has stood the test of time, reflecting its simple yet modern and clean design.

By Lim Tin Seng and Lee Peng Hui

Significant buildings in Singapore tend to fall into a few well-known categories. There are colonial-era buildings typically in the neoclassical style, like the former Supreme Court or the old Parliament House. Then there are stunning modern ones like Jewel Changi Airport, Marina Bay Sands and Esplanade – Theatres on the Bay. Not many of them, however, are 1970s homes located in leafy suburbs. Then again, not many buildings can claim to be the family home of the late architect and conservationist Lee Kip Lin.1

Designed by Lee and built in 1973, the house at 32 Binjai Park has been designated as a significant modernist building in Singapore.2

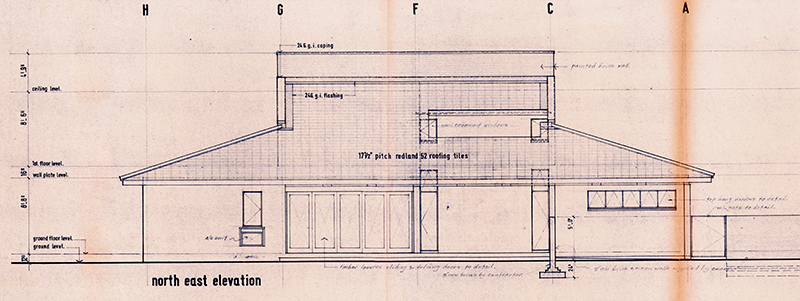

From the street, the 3,800-square-foot home (353 sqm) is unassuming, with its white-painted brick and plaster walls, and sloping, red-tiled roof. Although it does not stand out visually from its neighbours, it is when one walks through the front door that the unique qualities of the house are revealed.

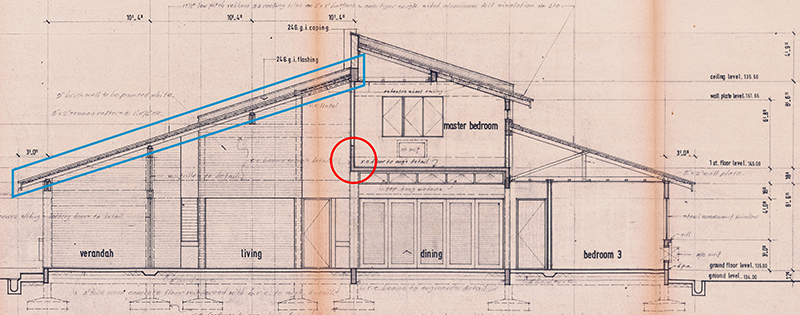

The house boasts a high ceiling with exposed timber beams and rafters as well as unobstructed, seamless access to the living room, dining room, veranda and garden. The open layout draws in natural light and breeze to create a spacious and airy feel, making the interior seem larger than it is.

The relatively modest house sits on 21,304 square feet of land (1,979 sqm), most of which is occupied by a garden where the grass has been allowed to grow out, allowing biodiversity to thrive. Taking centre stage is a tall, majestic Binjai tree, which has been listed as a heritage tree by the National Parks Board.3 Wild chickens can be seen pecking away, while the pet cat lazes nearby.

At dusk each day, Javan pipistrelles (a species of bat; Pipistrellus javanicus) emerge from within the frame of the sliding doors of the dining rooms where they have made their nests. They leave their hideaway to hunt before returning to roost at dawn. In the garden near the veranda is a wall made from red bricks salvaged from the former Raffles Institution building on Bras Basah Road.

Pioneer architect Tay Kheng Soon, a close friend and former student of Lee, describes 32 Binjai Park as “practical, tropical, refined and unassuming”.4 Peter Keys, co-author of Singapore: A Guide to Buildings, Streets, Places (1988), notes that the house “does not rely on any tricks or dramatic embellishments of any kind” to carry out its function as a family home.5 It is one of the few remaining houses in Singapore that still exists in its largely unaltered, original condition and bears characteristics from the late Modernism period of the 1970s.

A True Modernist

Associate Professor Tse Swee Ling from the Department of Architecture at the National University of Singapore described Lee’s design approach as pure and down-to-earth. “He did not do fanciful things like the post-modernists with a lot of decorations,” she said. “He did not believe in all that.”6

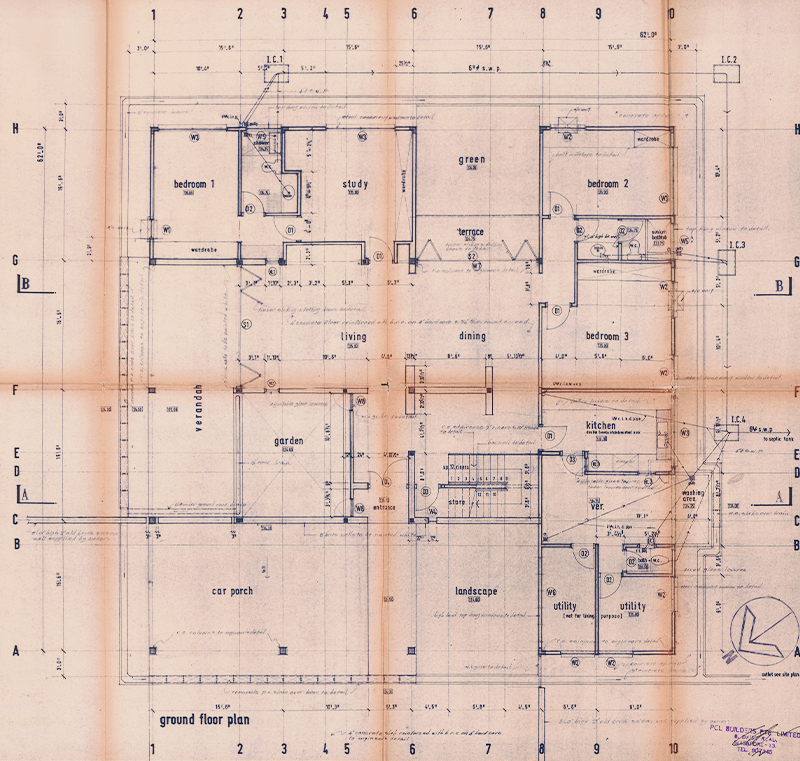

Tse had worked with Lee on many projects since the 1960s, including 32 Binjai Park. She pointed out that Lee’s home embodies his design philosophy. “The distinctive feature [of 32 Binjai Park] is the simplicity of the design,” she said. “The layout and setting are based on a simple square grid with recesses and void carved out. It is practically a single storey house except for the loft.”7

She noted that most people preferred double-storey houses, which made Lee’s home distinctive. The house is also notable for eschewing ostentatious flourishes. “In those days, in the area, which was a rich man’s area, the houses built there were much more elaborate,” she noted. While others used marble, Lee chose normal floor tiles. “I still remember he brought the tiles and showed me. He said, ‘I found these tiles. They are very nice for my house. What do you think? What do you think?’… He was so happy when he found the tiles.”8

Moving Out from Amber Road

Lee purchased the plot of land at Binjai Park in the early 1960s but he only started making plans to design and build a house on it in the latter half of the decade when he decided to move out from his family home on Amber Road.

The house in Binjai Park is very different from the Amber Road one. That was a two-storey seafront house, also designed by Lee after the earlier house on the same site was demolished in 1960. Only a wall with a gate stood between the garden and the beach.

In the Amber Road house, the dining room, kitchen and servants’ quarters were on the first floor. The living room, however, was on the second floor, and it opened to an extensive balcony. The balcony afforded panoramic views of the sea, ships and the Riau Islands beyond, which would not have been possible if the living room had been located on the first floor. From the balcony, Lee would often peer out, armed with a pair of binoculars.

Lee was very attached to Katong. He loved the sea and might never have left Amber Road if not for the Bedok-Tanjong Rhu reclamation works in the 1960s, which pushed the shoreline out. Another factor was the impending construction of the multistorey Chinese Swimming Club sports complex adjacent to the house. In addition, the tax on the vacant land at Binjai Park was extremely high compared to what it would have been if the property was occupied. Given all these, Lee decided to sell the house on Amber Road and move his family to Binjai Park.

A House for the Tropics

In designing his new home, Lee based the proportions of the house on a square grid, or module. This can be seen in the ground-floor plan of the house.

According to Tse, Lee revised the design concept of the house at least three times. The earlier designs featured a more basic grid layout. She said that when Lee first started planning, the house had an even simpler design. However, over time, he added new features like a garden and later a courtyard for ventilation. “If he didn’t have a courtyard, it would have been a large area with no lighting and no air and it would be very stuffy,” she said. “But you can’t see the courtyard from outside because of the veranda.”9

At one point, the house was even meant to be double-storey. But in the final design, it was reduced to one storey with a loft. From the outside though, the loft is not apparent. “The loft was just a small area above the entrance area,” she said. “But the look of the house is single storey, and if you look from outside, you do not know there is a loft.”10

Adding to the simple look is the use of brick walls to conceal the reinforced concrete columns inside the house. Lee used the rough finish of bricks as a contrast to the plastered walls. Tse added that Lee chose common bricks instead of “facing bricks”, which are used mainly for facades and hence more aesthetically pleasing.

Lee also did not want to install false ceilings. “He wanted to expose the roof construction by expressing the elements such as timber beams and rafters,” said Tse. “The concrete floor slab of the loft over the dining area was also left bare without a false ceiling. He had taken great care to place services such as the floor trap of the bathroom of the loft outside the house away from the main area so that a false ceiling is not necessary.”11

The design of the home also takes the local climate into consideration. Lee relied on the extensive use of louvres for windows and doors (some of which were bifold and trifold), which allows for cross-ventilation even when closed. The use of louvres also extends to the main entrance door.

While sliding glass windows and doors were coming into fashion about the time the house was built, Lee was adamantly opposed to them as he considered them to be unsuitable for the tropics: they cannot be fully opened and do not allow optimal use of the window and door apertures for ventilation.

Lee also chose to use a sloping roof instead of a flat one because of the torrential downpours that Singapore regularly experiences. Flat roofs are more likely to leak, which is why Lee gave his house – as well as every house he designed – a sloping roof. A sloping roof would also create a high ceiling that improves ventilation.

A Unique Character

The house today reflects both the original design as well as changes resulting from a major refurbishment that took place in 1997. This was necessary because many things had begun to deteriorate from wear and tear, including the original electrical wiring. The wiring had been embedded in the concrete walls, as was the practice in those days, and needed to be replaced. Lee was unwell by that time and was not involved in the work, which was supervised by his wife, Mrs Lee Li-ming.

She firmly dismissed suggestions to replace the original steel window frames and wooden doors with more “modern” alternatives. Although newer alternatives might have simplified the refurbishment, the look and feel of the house would have been irretrievably damaged.

One significant change that did occur during the renovation was the introduction of a false ceiling. Although this allowed the installation of recessed ceiling lights, it has subtly altered the appearance of the house, most evidently along the edges of the living room where the false ceiling ends. Thankfully, the false ceiling can be easily removed to restore the ceiling to its original height and purpose in the future.

A more recent addition is the installation of a large ceiling fan in the living room in 2013 – of the type more commonly found in public spaces such as MRT stations. Although the high ceiling made the house seem larger than it really was, an unintended consequence was that it gave the living room a rather cavernous feel, making it a less welcoming space. This changed when the large fan was installed, at the suggestion of architect Tay Kheng Soon. Apart from cooling the room, the fan has also made the living room cosier and therefore popular. Previously, guests would naturally gravitate to areas with lower ceilings, such as the veranda or what is now the TV room. Since the fan was installed, the living room has become more frequently utilised.

A Home for the Ages

In recent years, there has been an increased interest in Singapore’s modernist architecture.12 The public became more aware of modernist architecture here after the iconic Pearl Bank Apartments was demolished in 2019, despite international attention and proposals for conservation.13

The loss of Pearl Bank Apartments prompted the formation of the Singapore chapter of Docomomo International. Lee’s Binjai Road house has been included in Docomomo Singapore’s Modernist 100 list, joining other buildings such as Golden Mile Complex, Jurong Town Hall, Asia Insurance Building and the flats in Tiong Bahru built by the Singapore Improvement Trust.

Lee’s home is one of the few modernist homes in Singapore that has been opened for public visits. In March 2022, Docomomo Singapore organised two tours of the house, and tickets for both sold out almost immediately.14

In 2022, the family of the late architect donated the original architectural plans and documents, comprising contract drawings and correspondence between Lee and the firms involved in constructing the house, to the National Library, Singapore. These form part of the Lee Kip Lin Collection.15 The public may request to access the materials in the collection via the National Library Board’s catalogue at http://catalogue.nlb.gov.sg/. Walk-in requests can be made at the Level 11 information counter of the National Library Building on Victoria Street.

Lim Tin Seng is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. He is the co-editor of Roots: Tracing Family Histories – A Resource Guide (2013), Harmony and Development: ASEAN-China Relations (2009) and China’s New Social Policy: Initiatives for a Harmonious Society (2010). He writes regularly for BiblioAsia.

Lim Tin Seng is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. He is the co-editor of Roots: Tracing Family Histories – A Resource Guide (2013), Harmony and Development: ASEAN-China Relations (2009) and China’s New Social Policy: Initiatives for a Harmonious Society (2010). He writes regularly for BiblioAsia. Dr Lee Peng Hui is the son of Lee Kip Lin. He is an independent researcher and cultural commentator, who grew up surrounded by Singapore’s pioneer modernist architects. He has been observing the architectural scene in Singapore and abroad since the late 20th century.

Dr Lee Peng Hui is the son of Lee Kip Lin. He is an independent researcher and cultural commentator, who grew up surrounded by Singapore’s pioneer modernist architects. He has been observing the architectural scene in Singapore and abroad since the late 20th century.NOTES

-

Bonny Tan, “Lee Kip Lin: Kampong Boy Conservateur,” BiblioAsia 10, no. 3 (October–December 2014), 46–51; Joanna H.S. Tan, “Lee Kip Lin,” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published 2011. ↩

-

For a list of significant modernist buildings in Singapore, see “Modernist 100,” Docomomo Singapore, accessed 20 February 2023, https://www.docomomo.sg/modernist-100. ↩

-

“Binjai,” National Parks Board, 24 June 2021, https://www.nparks.gov.sg/gardens-parks-and-nature/heritage-trees/ht-2003-86. ↩

-

Tay Kheng Soon, “A Tribute to Lee Kip Lin,” in Big Thinking on a Small Island: The Collected Writings and Ruminations of Tay Kheng Soon, ed. Kevin Y.L. Tan and Alvin Tan (Singapore: Equilibrium Consulting Pte Ltd for Department of Architecture, National University of Singapore, 2020), 29. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 720.95957 TAY) ↩

-

Peter Keys, “Architects & Their Own Homes – The House of Lee Kip Lin,” In Times Annual Singapore 1983–1984 (Singapore: Times Periodicals, 1983–1984), 110–11. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 TAS-[HIS]) ↩

-

Tse Swee Ling, personal communication, 27 January 2023. ↩

-

Tse Swee Ling, personal communication, 27 January 2023. ↩

-

Tse Swee Ling, personal communication, 27 January 2023. ↩

-

Tse Swee Ling, personal communication, 27 January 2023. ↩

-

Tse Swee Ling, personal communication, 27 January 2023. ↩

-

Tse Swee Ling, personal communication, 27 January 2023. ↩

-

Modernist architecture emerged in the early 20th century. It is characterised by clean lines, simplicity, and a focus on practicality over ornamentation. Modernist architects use new materials and construction techniques to create functional and beautiful buildings that reflect the changing needs of society. See “Modernism”. RIBA Architecture, accessed 13 March 2023, https://www.architecture.com/explore-architecture/modernism. ↩

-

Justin Zhuang, “Saving Pearl Bank Apartments,” BiblioAsia 12, no. 3 (October–December 2016), 12–16. ↩

-

“Lee Kip Lin House Tour”. Docomomo Singapore, accessed 20 February 2023, https://www.docomomo.sg/happenings/lee-kip-lin-house-tour-event. ↩

-

In October 2009, the Lee family donated a collection of more than 19,000 items to the National Library, Singapore, forming the Lee Kip Lin Collection. It comprises monographs; annual reports of the Raffles Institution; letters and related documents of the East India Company; rare Singapore and Southeast Asian maps; slides and negatives of early and modern Singapore; and photographs taken by Lee Kip Lin. ↩