How the Raffles Museum Got a Whale Skeleton, Made It Famous, Then Let It Go 60 Years Later

The skeleton of a blue whale took pride of place at the former Raffles Museum for more than 60 years before it was gifted to the National Museum of Malaysia in 1974.

By Nathaniel Soon

Step into the Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum and one of the first things that will catch your eye is a 10.6-metre-long skeleton of an adult female sperm whale, Physeter macrocephalus (Linnaeus, 1758), taking centre stage at the museum’s gallery.

She had been found drifting off the coast of Jurong Island in July 2015. According to the museum, she had probably been hit by a ship as her dorsal hindquarters had a large wound, with broken backbones below the injury.1

Divers from the Maritime and Port Authority of Singapore first secured the enormous specimen with ropes, before towing it carefully across the West Johor Strait to the Tuas Marine Transfer Station. There, museum scientists commenced the arduous process of examination, dissection and recovery of the whale for eventual display.2

About eight months later, on 15 March 2016, Jubi Lee (thus named because she had been found the same year that the nation was celebrating its golden jubilee) was officially introduced to the public at the museum.

“As an older Singaporean, I am overjoyed by the return of a whale to our natural history museum,” declared Ambassador-at-Large Tommy Koh who was at the official launch.3 What Koh, who was the museum’s chairman, was alluding to was the fact that Jubi Lee’s skeleton is not the first whale skeleton to be exhibited in a museum in Singapore. Between 1907 and 1974, a 13-metre-long skeleton of a blue whale had been a popular attraction at the Raffles Museum (later renamed the National Museum).4

Ikan Besar Skali

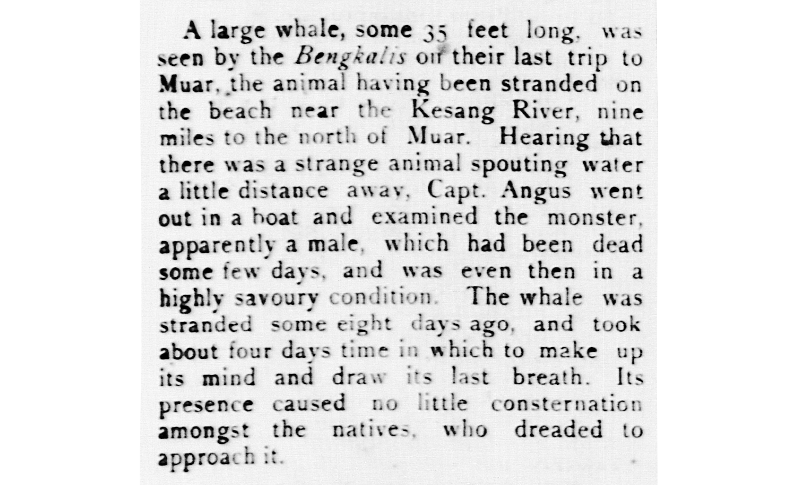

On 25 June 1892, the Singapore Free Press reported that the British steamer Bengkalis had spotted “a large whale” that was “stranded on the beach near the Kesang River, nine miles to the north of Muar”.5

The whale was presumed to have washed ashore somewhere around Sebatu, about 30 kilometres south of Melaka, eight days prior. It ultimately drew its last breath on 23 June 1892. According to the Straits Times Weekly Issue, the “fish of monstrous size (ikan besar skali)” was found to have measured 44 feet (13.4 metres) long and was “rather offensive and swollen with gases from decomposition”. The locals who encountered the specimen could not “call to mind ever having seen such a creature before”.6

D.F.A. Hervey, the resident councillor of Melaka, presented the local penghulu (chieftain) with a hadiah (gift) in exchange for the whale remains, which Hervey decided to preserve and convey to Singapore. A pagar (barrier) had been constructed around the carcass to “prevent it from getting washed back into the sea while the labourers worked” to dissect and prepare the remains for transportation.7

These arrived in Singapore later that year and was acquired by the Raffles Library and Museum (now the National Museum of Singapore) on Stamford Road. While the whale skeleton would go on to become one of the museum’s most iconic exhibits, it took 15 more years for it to see the light of day.

Owing to a lack of space in the building, the whale skeleton was locked up in a shed behind the museum compound before it was displayed. Knowledge about its origin and biology was at the time comparably obscure, admitted Karl R. Hanitsch, the museum’s curator and first director. Hanitsch and his staff quickly recognised that “more room” and “a number of much-needed alterations” were essential.8

Countless negotiations and debates ensued over the next several years. At last, a compromise was reached in 1904. The existing museum building was to be extended, with construction works commencing the same year and wrapping up in 1906.

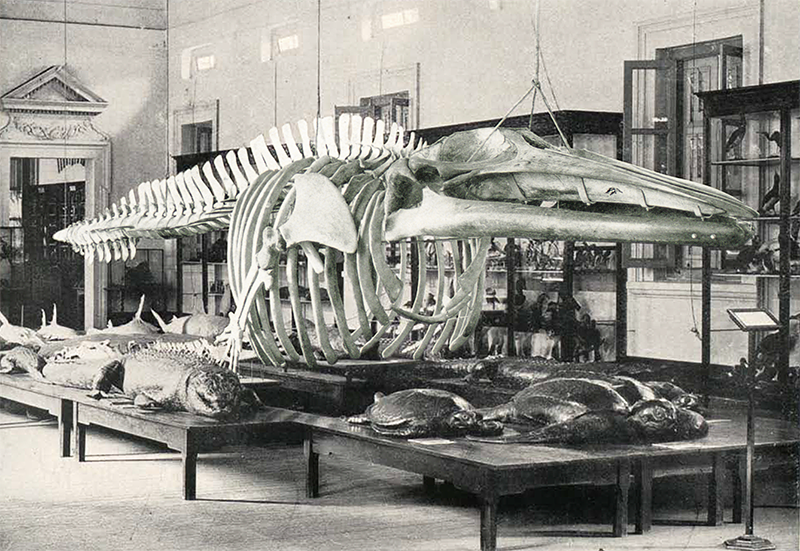

Thereafter, “a massive reorganisation was undertaken”, during which time the natural history specimens were refurbished and the large central gallery on the upper floor was designated as the home of the new zoological collection. Coinciding with the start of the Lunar New Year, the Raffles Museum reopened its doors to an “over-flowing by dense masses” of visitors on 13 February 1907.9

One particular exhibit stole the limelight. After years spent tucked away, the enormous skeleton of the beached whale finally made its public debut.

Whale Skeleton Reels in Visitors

Fitted with steel ropes, the skeleton hung proudly from the ceiling of the newly refurbished natural history room at the Raffles Museum. Assembling and mounting it was no easy task, and Hanitsch credited the ingenuity and hard work of the museum’s chief taxidermist Valentine Knight, his assistant Percy de Fontaine and their staff for finding workarounds in the process. The specimen had a couple of missing bones, including a scapula, the “hands”, and various vertebrae and ribs.10

With assistance from John Hewitt of the Sarawak Museum and Edgar Thurston of the Madras Museum, the Raffles Museum team took measurements and drawings of existing whale specimens and used them to model these missing bones out of wood and plaster of Paris. Only then was the full skeleton made available for viewing.11

Because this occurred before the advent of DNA technology, it took Hanitsch and his team several years before they could accurately identify the mammal. In an earlier report, Hanitsch had originally suspected the specimen to be that of a humpback whale, or Megaptera boops (Van Beneden & Gervais, 1880), but his subsequent morphological analyses would have been at odds with this earlier study. Further work allowed him to correctly identify the specimen as belonging to Balaenoptera indica (Blyth, 1859), which has since been synonymised as B. musculus (Linnaeus, 1758), more commonly known as the blue whale.12

The whale skeleton sparked significant interest and excitement among visitors. When the exhibit was being set up, an elderly Malay man came by and offered a first-hand account of the beaching of the whale. “Bukan satu kapal. Satu ikan!” (“Not a boat. A fish!”). He was, however, wrong on both counts – it was neither a boat nor a fish.13

The whale spawned a tale that was peppered with riveting detail. “Malays… told their boys the true story of the monster whale whose skeleton hangs suspended near the turtles. How the poor beast was stranded near Malacca and a pagar built promptly around him when for three days his bull-like roars terrified the neighbourhood, then silence and in seven days a corpse.”14

The giant skeleton also attracted international visitors from the wider scientific community. These included William Brigham, the American botanist and ethnologist and founding director of the Bernice P. Bishop Museum in Honolulu. Brigham, who had been on an inspection tour around the world, stopped by the Raffles Museum in 1912. He wrote about the whale in a “handsomely illustrated report”. Australian fisheries expert David Stead delivered a lecture titled “Life in the Sea” in 1922 to members of the Singapore Natural History Society, where he spoke passionately about whales and the biodiversity in the waters surrounding Singapore.15

The Raffles Museum gained an international reputation in the decades that followed, and its collections expanded significantly “as a result of expeditions in search of biological species, archaeological excavations and painstaking research”.16

In 1924, the museum underwent upgrading works, and the whale exhibit, which had been in the public gallery, was temporarily removed. Museum staff took the opportunity to refurbish and bleach the specimen before it was shifted to a new location. Now hanging from the ceiling right above the museum’s staircase on the second storey, the whale skeleton would remain at this spot for half a century, until the early 1970s.17

By 1948, a quarter of a million people had visited the Raffles Museum annually. It was slowly but surely emerging as a “historical landmark” far greater than the sum of its individual collections. “[T]he importance of [the] Raffles Museum stands out clearly when Singapore is the centre of a region which is, ethnologically and zoologically, one of the most intriguing in the world,” wrote the Singapore Free Press in 1960.18

After Singapore achieved internal self-government in 1959, the government saw the opportunity to mobilise the Raffles Museum to serve the island’s broader nation-building vision. Hence, in 1960, the existing institution was renamed the National Museum. While it inherited all the collections belonging to the old Raffles Museum, including the natural history exhibits, the new National Museum’s focus was instead on Singapore’s heritage and culture.19

The Singapore Science Centre, which began construction in 1971, inherited the natural history collection from the National Museum. However, the organisation’s mandate never covered taxonomic collection and identification. Members of its advisory board began searching for viable storage options for the over 126,000 zoological specimens, including that of the blue whale, which they found too large to accommodate. Indeed, these exhibits were “not only exposed to the risk of considerable material loss or damage” but were also “in danger of being disposed of and relegated to other institutions”.20

Whale Skeleton’s Fate Sealed

The authorities had to confront the fact that the whale, which had made the Raffles Museum famous, represented “little of Singapore’s own past”. In the early 1970s, the fate of the blue whale, which had enthralled visitors at the old Raffles Museum for over six decades, was more or less sealed.21

In 1972, the Science Centre donated what remained of the natural history collection to the Department of Zoology at the University of Singapore (now the National University of Singapore; NUS), where it was named as the Zoological Reference Collection. Over the next 15 years, the specimens were moved to various locations, including a storage facility at Ayer Rajah, different departments in the university and Nanyang University, before ending up at its permanent home at the science faculty of NUS in 1987.22

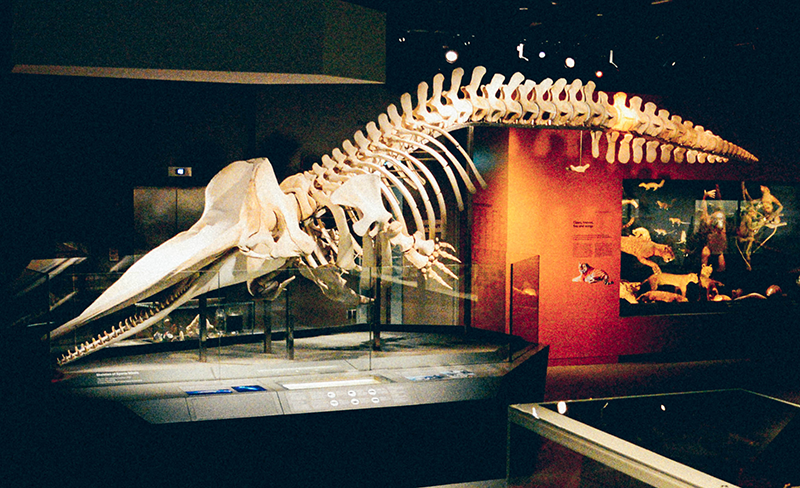

On 6 May 1974, the Straits Times announced that the Science Centre would be gifting the whale skeleton to the National Museum of Malaysia (Muzium Negara) in Kuala Lumpur. In return, the Malaysians would train Singapore’s museum staff on the “finer points of modelling and casting of exhibition specimens”. “The specimen will be one of the main exhibits at our museum and we expect it to become a main attraction,” said Syed Jamaluddin, then curator of Muzium Negara.23 (Presently, the whale specimen sits as the centrepiece in the Labuan Marine Museum, off Sabah, since its transfer there in 2003.24)

An outpouring of grief and regret followed the announcement. “It is like a personal loss to me. For as a child I never failed to look at it whenever I visited the museum. I have seen children looking at the vast structure with awe. It was one of the museum’s finest and most impressive exhibits,” wrote a reader to the Straits Times.25

The New Nation made the accusation that “local bodies were apparently not offered the opportunity to purchase the exhibits. Instead foreign organisations abroad were approached. The result is that a great section of the natural history collection which would have been the pride of any national museum is now out of the country… No amount of money can surely replace the sentimental attachment Singaporeans have for the items of historic importance”.26

The assistant director of the Science Centre, R.S. Bhathal, wasted no time in offering a sharp rebuke. He clarified that the complete zoological collection, minus the whale, remained in the country.

“The whale skeleton is not a pre-historic fossil which would be of great value to scientists who study pre-history…,” said Bhathal. “[It] does not lend itself to the Centre’s exhibits programmes [sic] and furthermore, there is just not the necessary space (which is needed so badly for the new exhibits)… to accommodate it… Eventually the Museum Negara approached the Science Centre for the whale skeleton. The Science Centre agreed to donate it to the Museum Negara in the spirit of goodwill and scientific co-operation.”27

Of Celebrations and Cetaceans

In 1987, the National Museum celebrated its centenary. To mark this milestone occasion, a selection of “historic fauna” like the crocodile, orang utan and leatherback turtle, all of which once called the museum home, were brought back for three weeks from 29 September to 18 October. To the disappointment of many, the returning zoological exhibits did not include the blue whale. Richard Poh, who was then the museum’s director explained: “Many people remember and ask about it, but unfortunately we can’t bring it back for the exhibition as it is in Kuala Lumpur.”28

The book, One Hundred Years of the National Museum, by Gretchen Liu was also produced to commemorate the museum’s rich history.29 In reviewing the publication, Irene Hoe of the Straits Times recounted: “As a child, I remember going to the museum – as often as I could persuade anyone to take me – to see ‘my whale’, ‘my tiger’, and ‘my snake’, among other treasures of natural history which packed the place… ‘My whale’, for instance,… sat in storage until a European taxidermist assembled it, suspended it from the ceiling with a steel rope and set it in my memory indelibly.”30

A groundswell of public interest for a proper museum dedicated to Singapore’s natural history was materialising. In 1998, NUS established the Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research to formally manage the Zoological Reference Collection. This institution, however, was more of a research centre with public display galleries.31

In May 2009, the museum set a record single-day turnout when it welcomed over 3,000 visitors during an event held in conjunction with International Museum Day. This prompted calls for a larger facility that could accommodate not only more people, but also the entirety of the museum’s showcase. That same year, NUS revealed plans for a full-fledged natural history museum that would replace the existing research centre.32

Coming Full Circle

The Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum opened its doors on 18 April 2015. However, even after having departed these shores for over 40 years, the old whale exhibit had not been forgotten. Claire Chiang, the senior vice-president of Banyan Tree Holdings, had donated a handsome sum to the museum. She spoke fondly of her visits to the National Museum as a child. “Of course, there was no air-conditioning then, but I remember the gorilla, the whale. It was such a fantasy place filled with many cabinets of curiosities. There was always something to explore. And I missed that when the museum changed.”33

The new museum was clearly still missing something: Jubi Lee’s debut in local waters a few months later could not have been more serendipitous.

“Jubi Lee is even better than the whale we gave away because it was found in our waters, because it belongs to a species seldom found in our waters, and because the skeleton is in perfect order,” said Ambassador-at-Large Tommy Koh.34 A fitting ending to a whale of a story.

Nathaniel Soon has a background in marine science and is a National Geographic Explorer. Through visual storytelling, he seeks to communicate science and connect people with our natural world.

Nathaniel Soon has a background in marine science and is a National Geographic Explorer. Through visual storytelling, he seeks to communicate science and connect people with our natural world.NOTES

-

Audrey Tan, “A Whale of an Exhibit,” Straits Times, 15 March 2016, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lim Yaohui, “Whale of a Find in Singapore,” Straits Times, 16 July 2015, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/whale-of-a-find-in-singapore/. ↩

-

Tan, “A Whale of an Exhibit.” ↩

-

Kate Pocklington and Iffah Iesa, A Whale Out of Water: The Salvage of Singapore’s Sperm Whale (Singapore: Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum, 2016). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 599.5470752 POC) ↩

-

“Correspondence,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 25 June 1892, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

R. Hanitsch, Guide to the Zoological Collections of the Raffles Museum, Singapore (Singapore: Straits Times Press, Limited, 1908), 13–14. (From BookSG; accession no. B02806775B); “Muar News,” Straits Times Weekly Issue, 29 June 1892, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Annual Report on the Raffles Museum and Library for the Year 1905 (Singapore: Government Printing Office, 1906), 3–4. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RRARE 027.55957 RAF); Kelvin Y.L. Tan, Of Whales and Dinosaurs: The Story of Singapore’s Natural History Museum (Singapore: NUS Press, 2016), 48–50. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 508.0745957 TAN) ↩

-

Annual Report on the Raffles Museum and Library for the Year 1905, 3–4. ↩

-

Gretchen Liu, One Hundred Years of the National Museum Singapore, 1887–1987 (Singapore: National Museum, 1987), 30. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 708.95957 LIU); Annual Report on the Raffles Museum and Library for the Year 1907 (Singapore: Government Printing Office, 1908), 4–5. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RRARE 027.55957 RAF); “Raffles Museum” Straits Times, 6 March 1908, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Annual Report on the Raffles Museum and Library for the Year 1907, 4–5. ↩

-

“Raffles Museum,” Straits Times, 6 March 1908, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Annual Report on the Raffles Museum and Library for the Year 1905, 3–4; Annual Report on the Raffles Museum and Library for the Year 1907, 4–5. ↩

-

“Sporting Trophies,” Straits Times, 16 January 1908, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Rambles in Raffles Museum,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (Weekly), 17 February 1910, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Raffles Museum,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 15 February 1916, 1; “Life in the Sea,” Malaya Tribune, 14 March 1922, 4. (NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lydia Aroozoo, “‘Redeeming’ Malayan History… Its Intriguing Work at Raffles Museum,” Singapore Free Press, 24 September 1960, 6. (NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Annual Report on the Raffles Museum and Library for the Year 1928 (Singapore: Government Printing Office, 1929), 3. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RRARE 027.55957 RAF) ↩

-

Aroozoo, “‘Redeeming’ Malayan History.” ↩

-

Alvin Chua, “Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum,” in Singapore Infopedia. From National Library Board. Article published 15 July 2020. ↩

-

Timothy P. Barnard, ed., Nature Contained: Environmental Histories of Singapore (Singapore: NUS Press, 2014), 179–211. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 304.2095957 NAT); Roland Sharma, “The Zoological Reference Collection: The Interim Years 1972–1980,” in Our Heritage: Zoological Reference Collection: Official Opening Souvenir Brochure (Singapore: National University of Singapore, 1988), 10. (From PublicationSG) ↩

-

Tan Sai Siong, “No Gimmicks Please, Just the Whole Singapore Story,” Straits Times, 31 October 1997, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Chua, “Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum.” ↩

-

“A Whale of a Gift for Malaysian National Museum,” Straits Times, 6 May 1974, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Labuan’s Century-old Whale,” Daily Express Sabah, 30 December 2006, https://rafflesmuseumnews.wordpress.com/2007/01/20/labuans-century-old-whale/. ↩

-

Make No Bones, About It, “Whale of a Loss,” Straits Times, 9 May 1974, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Loss of Those Exhibits…,” New Nation, 23 May 1974, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

R.S. Bhathal, “No Place for Whale,” New Nation, 10 June 1974, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Irene Hoe, “Nostalgia Theme of Bash,” Straits Times, 17 September 1987, 16; K.F. Tang, “Museum Brings Its Skeletons Out of the Closet,” Straits Times, 4 October 1987, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Liu, One Hundred Years of the National Museum Singapore, 1887–1987. ↩

-

Irene Hoe, “Museum’s Past Recorded for Posterity,” Straits Times, 3 October 1987, 32. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Tan, Of Whales and Dinosaurs, 182–83. ↩

-

Tan Dawn Wei, “Let’s Have a Natural History Museum for Singapore,” Straits Times, 14 June 2009, 26. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Deepika Shetty, “Giving Back to the Museums,” Straits Times, 28 April 2015, 2–3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Tan, “A Whale of an Exhibit.” ↩