The Curious Visit of Qing Ambassadors to Singapore

The visit by Qing officials to Singapore in 1876 led to the establishment of the first Chinese consulate here a year later.

By Benjamin J.Q. Khoo

On 13 December 1876, the P&O Steamer Travancore docked at Singapore carrying a curious entourage.1 Stepping off the ship were His Excellency Guo Songtao (郭嵩焘), the first Chinese ambassador to Britain, and other members of the Qing Imperial Court. It was about 11 on a grey, rainy morning when they arrived, with little fanfare to receive them. But after a run of four days at sea, it must have been a pleasant relief from the cramped quarters on deck as well as a temporal distraction from the weighty conversations between men and states.

This wet welcome on the island en route to Southampton, England, was brought about by a strange coup of diplomacy. The British, taking advantage of the murder of their consular official Augustus Raymond Margary by hostile tribesmen in China in 1875, had forced a treaty and apology from the Qing government. Under considerable pressure by the British legation, Beijing had caved in and consented to the despatch of an ambassador to the Court of England to “express their regrets” to Queen Victoria herself (带国书前往英国,对滇案表示“惋惜”). This fresh embarrassment, despite the nebulous style of officious phrasing, added to the series of humiliating reversals and defeats, which shook the dynasty’s confidence as a world power.

Assembling the Embassy

The British were eager to underscore to the watching world the pre-eminence of Great Britain. So it was not more than four months after the signing of the Chefoo Convention on 21 August 1876 (or the Yantai Treaty, 烟台条约) to resolve the “Margary Affair” that the embassy assembled and departed from Shanghai.

Under the direction of Halliday Macartney, one of two Englishmen attached to the visitors, he made it a point that the Chinese delegation would call only at British ports, on the so-called “six great stages of our Imperial track across the Oceans, viz. Hong Kong, Singapore, Ceylon, Aden, Malta and Gibraltar”, where they could be impressed by the luminosity of England’s enlightenment and their undeniable mastery of peoples, land and sea.2

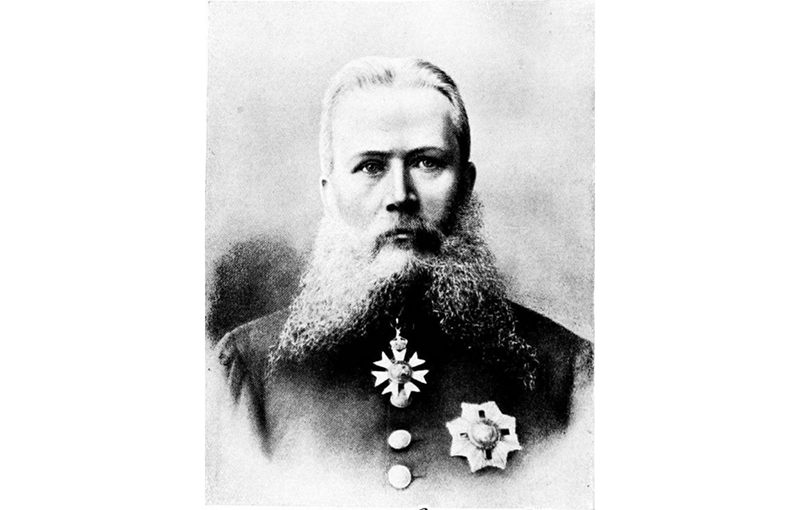

On the Chinese side, spirits were low and there was difficulty finding a suitable ambassador to fill the post. During this period, a despatch overseas was akin to exile rather than a lucrative honour. Eventually, Chinese premier Li Hongzhang appointed Guo for the post. A seasoned statesman, Guo was a strong advocate of liberal reform and favoured negotiation with the “foreign barbarians”. His keen attention to Western affairs was atypical for his time and invited slander, suspicion and distrust from his enemies.

For this trip, Guo was accompanied by other Chinese bureaucrats who failed to share his outlook, plaguing the voyage with much schism and infighting. Drawing his particular ire was the minor official Liu Xihong (刘锡鸿), who was attached belatedly as assistant envoy to the embassy, likely as a check on Guo’s liberal leanings.3 Liu was a quarrelsome individual with a reputation for xenophobia, stubbornness and ignorance.4

It is under this cloud of undue politicking within the Qing court and the outsized influence of the British legation that the embassy called at Singapore in the second regnal year of the Guangxu Emperor (光緒帝; r. 1875–1908).

Arriving in Singapore

The tour of Singapore, intended as an elaborate exercise in imperial pageantry and propaganda,5 made a strong impression on the visiting Chinese emissaries, even if its beginnings were slightly unpropitious.

Upon landing, the visitors were met by William A. Pickering, the Chinese interpreter, who was among the first to receive them on the wharf. Macartney described him as “a common-looking person and seemed to feel his inferiority too much” although he conceded that “[Pickering] seemed a good fellow and to have some sterling qualities”.6

Pickering could only apologise for the delay of the colonial secretary, John Douglas, due to the steamer having arrived earlier than expected. Douglas subsequently came to present his compliments but regretted that a proper reception in the form of a 15-gun salute and a guard of honour had to be prepared. This meant that a meeting with William Jervois, governor of the Straits Settlements, was embarrassingly postponed until four in the afternoon.

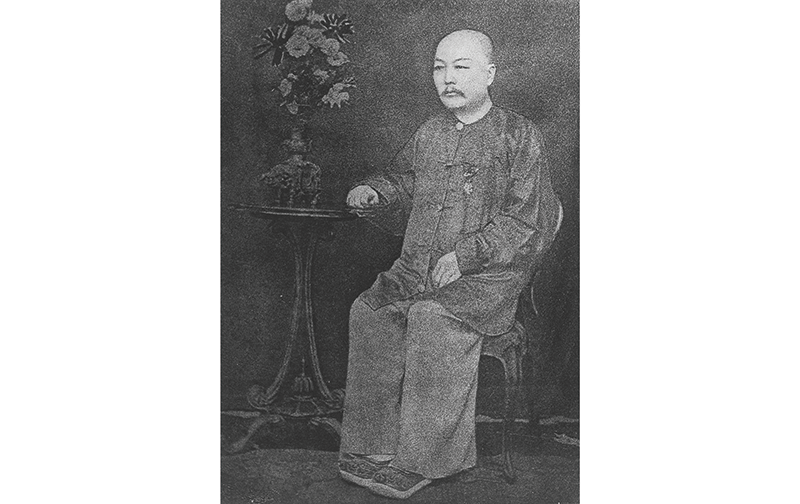

Meanwhile, as the party adjourned for refreshments, they were joined by Cai Guoxiang and Cai Guoxi, officials of the Yang Wu, a Qing corvette launched by the Fuzhou Shipyard in 1872.7 Accompanying the crew were some Singapore merchants, among them a certain Hoo Ah Kay (Hu Xuanze; 胡璇泽), more popularly known in Singapore as Whampoa (he was born in Whampoa [Huangpu], near Canton [Guangdong], China).

A Cantonese with uncanny business sense and an uncommon mastery of English, Hoo had forged a successful relationship as a ship chandler, supplying provisions to the British Royal Navy while maintaining business liaisons with other European businesses, climbing the ranks to become one of the foremost personalities in the colony. By this time, he was already an extraordinary member of the esteemed Executive Legislative Council of the Straits Settlements (the first and only Chinese) and had become the first Chinese to receive the CMG (Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George).8 A distinguished, thinly moustached man of 60, Hoo was now paying a visit to the latest dignitaries to appear on Singapore’s shores.

Whampoa’s House

Perhaps upon the insistence of Hoo, who took advantage of the delay on the governor’s part, the Chinese visitors accepted the invitation to see his house and private garden ahead of the meeting with the governor at Government House (known as the Istana today). Today, Hoo’s residence and garden, formerly located off Serangoon Road, no longer exist but in its heyday, it was a celebrated paradise of horticulture, famous for its tasteful recreation of rockeries, ponds, bonsais and bamboo, and a rare gathering place for public celebration during the Lunar New Year.

Steeped in the aesthetics of Chinese gardens, the Nam-sang Fa-un (南生花园), as it was known in Cantonese, gave form and elegance to the merchant’s wealth.9 The Russian novelist Ivan Goncharov, who had visited in July 1853, was amazed by the variety of greenery such as banana trees, water lilies, pepper plants, sago, breadfruit trees and bamboos. He also described the pens of birds and animals, towers with latticed turrets for doves, and noted the presence of a beautiful Arabian horse, completely white. The house was even more fabulously adorned, laid with mats and everywhere pieces of furniture “of delicate carvings, gilded lampshades, long covered galleries with all the appurtenances of refined luxury: bronzes, porcelain, on the wall statuettes, arabesques”.10

Very much against the wishes of Macartney, who tried to dissuade them of this undertaking, the party went along, taking the road from New Harbour to Bendemeer after two in the afternoon. The rain having cleared, and the sun now bearing down hotly upon them, they were carried on four carriages, probably ordered by Hoo.

Macartney was eager that no dishonour be seen to impinge upon British governance, but almost true to his fears, as they passed Indian and Chinese shophouses, the visitors, upon reading the signboards on the Chinese shophouses, remarked that the Singapore Chinese “seemed for the most part to be very poor”.11

Flustered by this comment, Macartney rejoined hastily that they “had not yet arrived at the town, and that these houses could not be taken as fair specimens of the shops of their countrymen”.12 It did not help that their coachman drove them to his shop rather than high-roading the way to the luxurious house of Hoo. Chagrined, Macartney leapt out angrily from the carriage and asked one of the shop assistants to “give the necessary directions for our being taken with all possible haste to Mr. W’s [Hoo’s] house”.13

Fortunately, things went relatively well at Hoo’s house and garden, where the visitors passed an agreeable midday. In his journal, Guo wrote that he was transfixed by Hoo’s collection of exotica as “has seldom been seen before” (多未经见).14 Guo also described the glass case containing an antelope’s head with horns attached, the sword of a swordfish seven feet in length, a six-legged tortoise and a domestic, live and bounding kangaroo, the last of which he seemed most surprised to finally see outside of tales and books.15

This collection of animal parts spoke to a long Chinese tradition of venerating such items for their medicinal and mystical properties, their symbolic associations and as tangible markers of power and wealth.16 Guo, while dazzled by Hoo’s collection, did not let this distract him from serious political discussions. Likely in Hoo’s garden, Guo sounded out his thoughts on a potential appointment as Singapore’s Qing consul to China.17

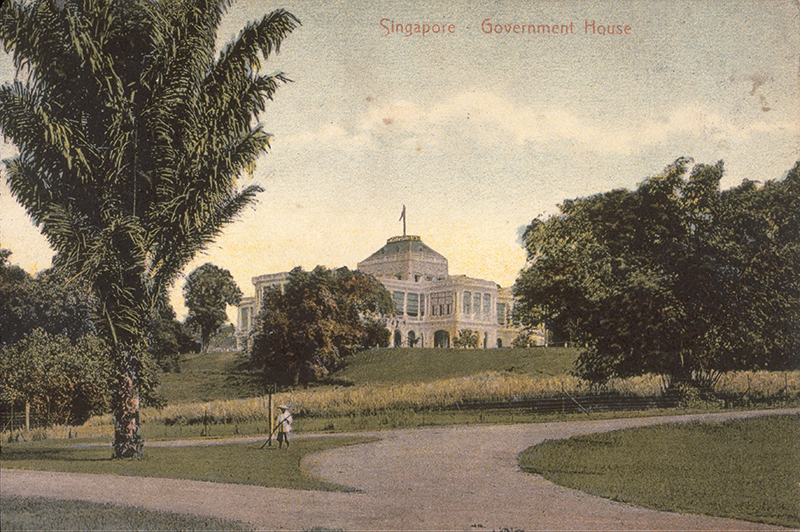

By 4 pm, the envoys were back on track on more officious proceedings. Guo and his suite finally met Governor William Jervois and his family at Government House. The conversation appeared rather superficial, although Guo had only positive things to write. He described the governor as more affable in bearing than the governor of Hong Kong, Arthur E. Kennedy, and his lady as “very intelligent and most sympathetic in her enquiries” (夫人亦贤明, 慰问甚勤).18

The company was then escorted to Fort Canning where they inspected the fortifications along the hill, and visited the barracks and troops. Here it was defensive bulwarks, the serious firepower of the artillery, the professionalism of armies and the rigid division of labour that were conveyed successfully to the Qing visitors.

The Tour Continues

The second day continued in much the same vein although, as was customary of a December in Singapore, it was accompanied by rain and thunder. With the indefatigable Pickering, Guo and his officials visited the corvette Yang Wu. The ship had made a run from Calcutta and onboard, the crew put on a display of guns and drill, as well as firing salutes for the visiting dignitaries.

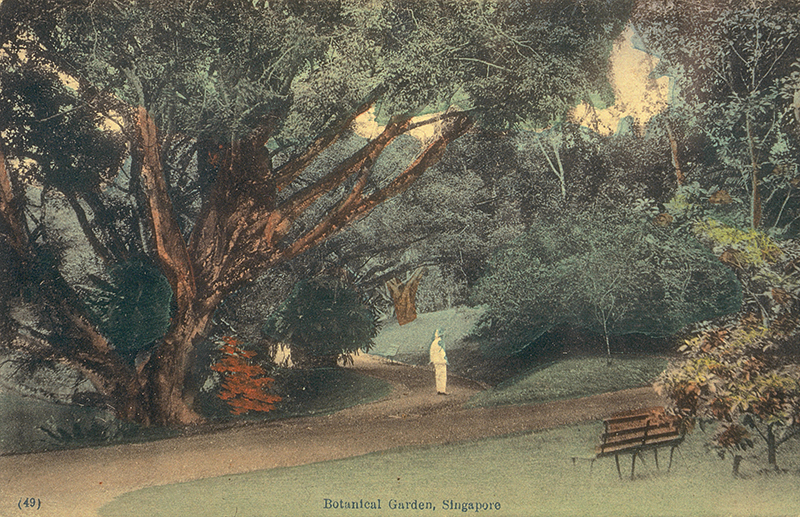

Pickering then arranged for the Hong Gardens to be next on the list of destinations to visit. Reckoned by Guo to be a public park to be enjoyed by the Chinese inhabitants of the city, this was in fact the reconstituted Botanic Gardens, complete with an in-house zoo; the latter recently opened to the public in 1874.19

Guo must count as one of the early visitors who were enthralled and delighted by the range of animals on display, and he took great pleasure in describing the tiger and leopard dens, the Tibetan bears, dogs, wolves, weasels, squirrels and beavers set against the lush shade of trees and flowers.

The Botanic Gardens impressed Guo greatly, rivalling his enjoyment of Whampoa’s private garden and menagerie. Unaware of the troubles that had plagued the zoological upkeep, Guo was much taken by the variety of wild beasts and strange birds on show, one so tamed and caged, the other so colourful and beautiful in plumage. He was also very much struck by the strange and wonderful plants that he saw: the extraordinary heights of cultivated pines, the flowering wisterias “shutting out the sky like a huge screen”, and the wide spreads of palm leaves that seemed like “great fans”, found everywhere.20

Beyond the anomaly that public gardens were unknown in China at the time, Guo was most struck by nature’s estate as “a triumph of human ingenuity” (足见此园魄力之大矣).21 Never before had he seen so much labelling and categorisation, so much diversity and individuality of species collected together in a single space. It was the triumph of order, demonstrated here over nature, which was one of the qualities that Guo thought China lacked.

Evidently, Guo counted this garden visit one of his highlights in Singapore, pleasing the ambassador so much that he praised this diversion in his journal. “At that time, I thought I should concentrate on practical administrations and not fritter away my time in sightseeing for entertainment,” he wrote. “Yet now, quite unexpectedly, I have come across these strange sights which have filled my heart with intense delight (前至香港,有导游花园者,谓当观览其实政,不以游赏为娱,今无意中得此奇景,亦殊惬心).”22

A final courtesy call was made to the courthouse, where the visitors attended a hearing presided over by Judge Theodore Ford. It is here that the panoply of the magistrate’s court impressed Guo with its order and solemnity, in sharp contradistinction to the noise and wrangle of Chinese proceedings.

Then, with time being short, preventing hence a visit to the local schools, the entourage met with Governor Jervois once again in the late afternoon before departing hurriedly, setting sail again for Penang. So ended the two-day Qing tour of Singapore.

An Unexpected Outcome?

The visit, even though it was of so short a duration, was to have some consequence. Stirred by his own experience and investigations in Singapore, Guo started negotiating with the British Foreign Office once in London on the possibility of setting up a consulate in Singapore.23 This was ostensibly with the aim of protecting the Chinese and to develop a similar European-style diplomatic corps in China. But a more crucial reason was the eye towards extending its influence on the overseas Chinese that still maintained ties with their motherland. In particular, the centrality of the Chinese in Singapore, their aspirations and their wealth – as exemplified by Hoo – were seen as potential assets to the Qing court.24

This was a fortuitous opportunity for Hoo, whose efforts to entertain the Chinese dignitaries were amply rewarded when he was nominated as the first Qing consul of Singapore, thereby substantially enhancing his portfolio and prestige in his adopted land. Indeed, it was considered a great achievement for him, an overseas Chinese migrant, to enter the ranks of the imperial Chinese bureaucracy. Guo had envisioned this to be a first step towards Qing consular expansion, with Singapore potentially acting as the head office for a series of consulate establishments throughout Southeast Asia, but this ambitious plan was set aside due to lack of finances.25

Meanwhile, alarmed by Guo’s negotiations in London to set up a consulate in Singapore, the British quickly established the Chinese Protectorate – with Pickering appointed as the first Protector of Chinese – in Singapore in May 1877. The Qing Consulate officially came into being on 5 October, five months later. The quick succession of the two offices would breed much conflict and rivalry in Singapore with regard to the protection of Chinese migrants in the years that followed.26 Nevertheless, the establishment of the consulate counts as perhaps one of the few Qing successes from this pivot to the West.

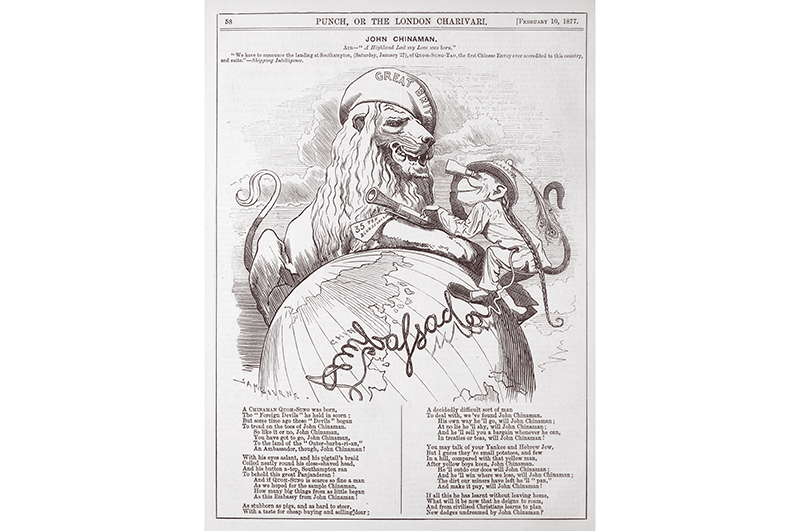

As for Guo, the embassy he headed eventually made it to London in early 1877, where he passed an eventful two years as the first Chinese ambassador, turning his eyes and mind to international issues of diplomacy and law while grasping at the same time the peculiar contours of Western man and society. Despite seeking answers to China’s response to the West and establishing diplomatic relations with Germany and France in subsequent years, he was unable to push his insights to a divisive court in Beijing.27 Most mortifyingly, he was mocked by the jingoistic and vitriolic tabloids in a foreign land while bearing the scorn of his countrymen at home.28

After this diplomatic posting, Guo eventually retired to his estate in his native Hunan to pass his remaining days quietly, teaching and writing his memoirs. Ever the conservative, Liu eventually returned home where he took up a post in the Court of Banqueting.29 (Liu, who left no impression of his time in Singapore, had also sabotaged Guo by sending malicious slanders to Beijing while in London.30)

A Forgotten Encounter

In January 1878, an abbreviated extract from Guo’s diary (使西纪程)31 talking about his sojourn in Singapore managed to find its way into the Singapore Daily Times.32 That aside, the brief sojourn by Guo and Liu has largely been forgotten.

Nonetheless, the entire episode illustrates, then and now, how quickly the face of Asia was changing towards the tail end of the 19th century. In particular, it provided a painful assessment of the gap that had emerged between China and the West. The centrality and superiority of Imperial China were being challenged everywhere.

At the same time, through the visit of the Qing emissaries, we see how Singapore, as a colonial showpiece, was firmly embedded in the pageantry of British power, exerting with its admixture of influences and oftentimes garish contrasts – of privilege and underclass, of wealth and poverty, of promise and danger, of progress and backwardness, of order and disorder – a strange fascination for visitors near and far.

Much, of course, has changed since – Britain has lost its empire, China is a global power and Singapore is an independent, sovereign state. However, Chinese holidaymakers still descend on Singapore in December each year, visiting many of the same spots that once enthralled the Qing visitors of the 19th century. Occasionally battling inclement weather, the tourists enjoy the sights at the Istana, the Botanic Gardens and Fort Canning. They also visit parks, admire old shophouses and walk on our streets. The same sense of wonder, the same sense of familiarity, the same sense of possibility reverberate like echoes from the past into the present.

Benjamin J.Q. Khoo is a Research Associate at the Asia Research Institute and a 2020/21 Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow at the National Library, Singapore. He has worked on Singapore before the modern era and he is interested in networks of knowledge and diplomatic encounters in Asia.

Benjamin J.Q. Khoo is a Research Associate at the Asia Research Institute and a 2020/21 Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow at the National Library, Singapore. He has worked on Singapore before the modern era and he is interested in networks of knowledge and diplomatic encounters in Asia.Notes

-

“Arrivals” Straits Times, 16 December 1876, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Demetrius C. Boulger, The Life of Sir Halliday Macartney, K.C.M.G. (London: John Lane, 1940), 265, Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/lifesirhalliday00boulgoog. ↩

-

Theodore Huters, Bringing the World Home: Appropriating the West in Late Qing and Early Republican China (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2005), 33. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. R 895.109005 HUT). ↩

-

See, for example, Zhang Yuquan 张宇权, “Wan qing waijiao shishang de yidian yiwen: Lun guosongdao yu liuxihong de guanxi” 晚清外交史上的一点疑问: 论郭嵩焘与刘锡鸿的关系 [A question in the diplomatic history of the late Qing dynasty: On the relationship between Guo Songtao and Liu Xihong], 公共管理研究, 2005, https://www.sinoss.net/uploadfile/2010/1130/4913.pdf. ↩

-

See Donna Brunero, “Visiting the ‘Liverpool of the East’: Singapore’s Place in Tours of Empire,” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 50, no. 4 (December 2019): 562–78, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-southeast-asian-studies/article/abs/visiting-the-liverpool-of-the-east-singapores-place-in-tours-of-empire/66DDBD2E285CCE576492216A3E6A4192. ↩

-

Boulger, Life of Sir Halliday Macartney, 275. ↩

-

“Thursday, 14th December,” Straits Times, 16 December 1876, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Song Ong Siang, One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore (Singapore: University of Malaya Press, 1967), 180–81. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.57 SON) ↩

-

Maggie Keswick, The Chinese Garden: History, Art and Architecture (London: Frances Lincoln, 2003), 44. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. SBG R 712.0951 KES) ↩

-

Ivan Goncharov, The Frigate Pallada (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1987), 235–36, Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/frigatepallada00gonc. ↩

-

Boulger, Life of Sir Halliday Macartney, 276. ↩

-

Boulger, Life of Sir Halliday Macartney, 276. ↩

-

Boulger, Life of Sir Halliday Macartney, 276. ↩

-

The First Chinese Embassy to the West: The Journals of Kuo Sung-T’ao, Liu Hsi-Hung and Chang Te-Yi, trans. J.D. Frodsham (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1974), 13. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 327.20922 FIR); Guo Songtao 郭嵩焘, Shi xi ji cheng 使西纪程 (Beijing 北京: Zhong guo lüyou chuban she 中国旅游出版社, 2016), 7. (From NUS Chinese Library) ↩

-

Frodsham, First Chinese Embassy to the West, 14. ↩

-

Liz. P.Y. Chee, Mao’s Bestiary: Medicinal Animals and Modern China (Durham: Duke University Press, 2021), 5. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Yan Qinghuang, Coolies and Mandarins: China’s Protection of Overseas Chinese During the Late Ch’ing Period (1851–1911) (Singapore: Singapore University Press, 1985), 142. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 325.2510959 YEN-[GH]) ↩

-

Frodsham, First Chinese Embassy to the West, 14. ↩

-

Timothy P. Barnard, Nature’s Colony: Empire, Nation and Environment in the Singapore Botanic Gardens (Singapore: National University of Singapore Press, 2016), 92. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 580.735957 BAR); See also Gilbert E. Brooke, “Botanic Gardens and Economic Notes”, in One Hundred Years of Singapore, ed. Walter Makepeace, Gilbert E. Brooke and Roland St. J. Braddell, vol. 2 (London: John Murray, 1921), 63–79. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.51 MAK-[RFL]) ↩

-

Frodsham, First Chinese Embassy to the West, 17-18. ↩

-

Frodsham, First Chinese Embassy to the West, 18. ↩

-

In Hong Kong, Guo had refrained from visiting gardens; 郭嵩焘, 使西纪程, 9. ↩

-

Frodsham, First Chinese Embassy to the West, liii, 76; Cai Peirong 蔡佩蓉, Qing ji zhu xinjiapo lingshi zhi tantao (1877–1911) 清季驻新加坡领事之探讨 (1877–1911) [A discussion on the consulates in Singapore in the Qing Dynasty (1877–1911)] (Xinjiapo 新加坡: Xinjiapo guo li da xue zhong wen xi 新加坡国立大学中文系, 2002), 34. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. Chinese RSING 327.51 CPR) ↩

-

Cai, Qing ji zhu xinjiapo lingshi zhi tantao, 34. ↩

-

Yan, Coolies and Mandarins, 142. ↩

-

Lim How Seng, “Rivalry Between Straits Settlements Government and Chinese Consulate in Singapore (1877–1894),” in A General History of the Chinese in Singapore, ed. Kwa Chong Guan and Kua Bak Lim (Singapore: World Scientific, 2019), 186. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 305.895105957 GEN) ↩

-

See Tong Qingsheng, “Guo Songtao in London: An Unaccomplished Mission of Discovery,” in China Abroad: Travels, Subjects, Spaces, ed. Elaine Yee Lin Ho and Julia Kuehn (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2009), 45–62. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSEA 304.8089951 CHI) ↩

-

Frodsham, First Chinese Embassy to the West, i–iiv. ↩

-

Frodsham, First Chinese Embassy to the West, lx. The Court of Banqueting, or Guanglu Si (光禄寺), was the department responsible for providing food and drink for special occasions, such as for tributary feasts. See Richard J. Smith, The Qing Dynasty and Traditional Chinese Culture (Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2015), 101. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. R 951.03 SMI) ↩

-

Laurence Wong, “‘Entrance into the Family of Nations’: Translation and the First Diplomatic Missions to the West, 1860s–1870s,” in Translation and Modernization in East Asia in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries, ed. Lawrence Wang-chi Wong (Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press, 2017), 201. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

For the Singapore leg of Guo’s journey, see 郭嵩焘, 使西纪程, 7–9. ↩

-

“H.E. Kwoh Sung Tao’s Diary. H.E. in Singapore,” Singapore Daily Times, 21 January 1878, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩