The Salvation Army in Singapore

The history of the Salvation Army in Singapore goes back to at least 1935.

By Lee Geok Boi

Today the Salvation Army is a well-known institution in Singapore. Its thrift stores are popular with bargain hunters and those on a budget. During the Christmas season, its bell ringers, with their bright red kettles, are a common sight outside shopping mall entrances as they seek donations from passers-by.

However, back in March 1935 when Lieutenant-Colonel Herbert A. Lord of the Salvation Army in Korea first came on a reconnaissance mission to see if colonial Singapore needed its help, the Army was not particularly well known. Lord told the Straits Times that he was here to “investigate the possibilities of his organisation undertaking religious and social work in this city”.1

Salvationists, as members of the Army are called, had been doing work in Southeast Asia as early as 1898 at the invitation of the Dutch government in the Dutch East Indies.2 In Java, the Army had taken charge of the leper, criminal and pauper populations. Like the British colonial administration in Singapore, the Dutch East Indies government did not have a social work agency.

There were apparently early attempts by the Army to proselytise in Singapore at the beginning of the 20th century. According to the Straits Budget in 1936, the “uniform of the Salvation Army was first seen in Singapore about 30 years ago, when one of its representatives was booed on the Esplanade”.3 The news report added that the Army was “facing prejudice and hostility all over the world owing to the novelty of its methods”.

One reason could be that the Army evangelised through open-air meetings where men, as well as women, preached and sang accompanied by musicians, good and bad. Could the Salvationist who was booed at the Esplanade have been no less than the founder of the Army himself, General William Booth?4 The Eastern Daily Mail and Straits Morning Advertiser had reported in November 1906 that Booth was heading to Japan to inspect the Army’s mission that had started there in 1895.5

In the days of steamship travel, Singapore would have been a likely stopover enroute. In 1926, General Bramwell Booth, son of William Booth, on his way to Japan, had stayed long enough in Singapore to give a talk at the Victoria Theatre on the work of the Army in December that year.6 Organised by the Dutch Indies Salvationists, the talk could have also been intended as a fundraiser, for it was by invitation only and “Eurasians and Asiatics” who turned up uninvited were kept out until all the invitees were seated. Even with uninvited guests though, the Victoria Theatre had empty seats.7

Two days later, the Malayan Saturday Post commented somewhat snarkily that “the arrangements for the public lecture by General Booth on Thursday [2 December] at the Victoria Theatre were the most stupid imaginable”. “It is to be hoped that if the Salvation Army is to start work here arrangements would be left in the hands of more capable officers to carry out the work in the spirit of the founder and that there would be no hankering after the high and mighty.”8 However, a reporter from the Malaya Tribune who had attended the same talk reported that a “packed house greet[ed] General Bramwell Booth”.9

First HQ at 47 Killiney Road

It took Herbert Lord a month to write up his report, get approval from London and set up the Army’s modest base in a shophouse at 47 Killiney Road, where the Lord family lived on the floor above. It also had a post office box number.10

Lord found 10 Salvationists among the British troops stationed in Singapore whom he expected to form the core of the movement. “[The Salvation Army] will be on evangelical lines first and foremost, and social work will also be important particularly when additional funds are available,” Lord told the Straits Budget in April 1935. Funds did become available almost immediately. In June 1935 the Army was roped in to handle the Rotary Club’s unemployment relief fund project.11

During the Great Depression in the early 1930s, unemployment was high in Singapore. Formed in 1930, the Rotary Club had, in 1935, begun fundraising among its professional and wealthy membership to disburse cash to the unemployed. Soon afterwards, the colonial government started the Silver Jubilee Relief Fund as an endowment fund to commemorate the Silver Jubilee of King George V.12

Before long, the government was also calling on the Army to help with the distribution of relief money from the Silver Jubilee Fund. Captain Frank Bainbridge, who had been the Relieving Officer for the Rotary Club Relief Fund, was made the Relieving Officer for the Silver Jubilee Fund, which began distributing money in April 1936.13 Bainbridge was put in charge of all aspects of this cash distribution. The Army was also represented on the Silver Jubilee Fund committee on which Lord, now a Brigadier, sat as a member.14

The Army’s open-air services were held initially at the Esplanade, but it also had the use of the hall of the Young Men’s Christian Association in their Orchard Road premises during the rainy season.15 One popular location was the Municipal bandstand on Waterloo Street. In a town with few entertainment options at the time, such singing and loud music, albeit laced with preaching and calls to repent, would have attracted attention. The Army also took the opportunity to solicit donations at these services.

However, in 1954 when the Army tried to resume its open-air services at the Esplanade, its application to the City Council was turned down. “The committee’s decision was a firm ‘no’ having regard to the number of religious sects in Singapore and the character of the Esplanade Walk,” reported the Straits Budget.16 The council was afraid that the Esplanade would turn into a “Hyde Park Corner”.17

Homes for Boys and Girls

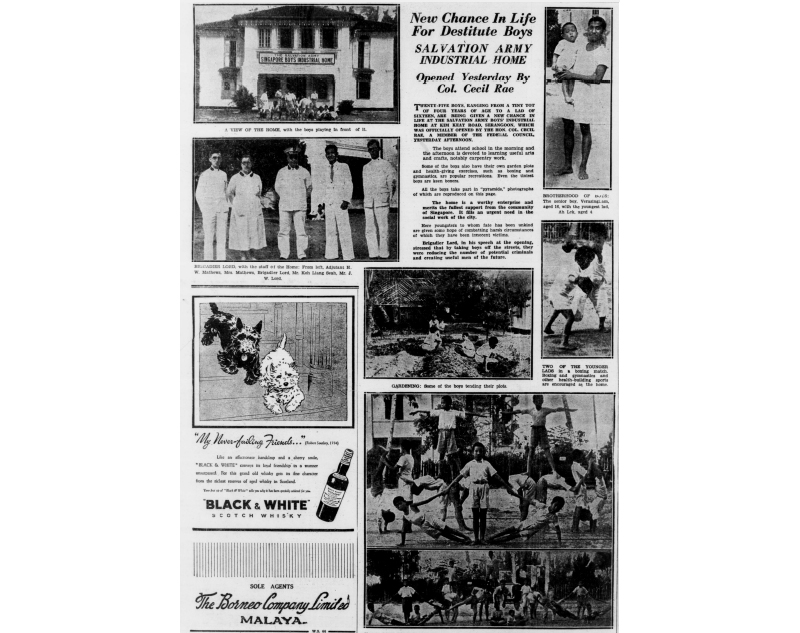

By 1936, the Army had two homes in operation. One was the Boys’ Industrial Home on Kim Keat Road, whose aim was to rehabilitate delinquent youths by teaching them employable skills such as woodwork and carpentry, giving them a basic command of English and guiding them on how to lead a good Christian life. In his opening speech, Lord said that by “taking boys off the streets, they were reducing the number of potential criminals and creating useful men of the future”.18

In March 1937, the home moved to new premises at 151 Thomson Road to accommodate more boys.19 A separate remand home subsequently opened in the same building to house boys convicted of juvenile offences.20

The other was the Women’s Industrial Home at 36 Paterson Road, which took in troubled or delinquent girls in their late teens.21 Speaking at the official opening of the home in February 1936, Lord said: “[T]his home would become a refuge that would provide freedom from the influence of evil temptation and companions; provide instruction in the consequences of an evil life and the possibility of a virtuous one; give an opportunity to create new habits and nurture these habits in helpful surroundings; train girls in those things that would enable them to work; and create a centre from which those women could be sent out to useful positions in life and from which loving and watchful care could be exercised over them until they become permanently re-established.”22

Some of the girls were rescued from a life on the streets by Salvationists who, dressed in their iconic white uniforms, hung out in red-light districts talking to the girls and offering them an opportunity for a different way of life. Mrs Herbert Lord, wife of the head of the Army in Singapore, speaking at a Rotary Club meeting in February 1941, said: “During 1940, 200 hours were spent on the streets, meeting the girls both in the streets and in the cafes; more than 100 cafes and cabarets were visited by Salvation Army women officers in uniform for the sole purpose of meeting and offering assistance to any girls who were willing to be helped.”23

Tan Beng Neo, a resident of the Women’s Industrial Home, who later became a social worker, also acted as a translator for the European Salvationists on these night patrols. In her oral history interview, she said: “If they don’t like us they would walk away… Well, we don’t chase after them. But some of them greeted us… when they start to know that we were not doing any harm to them except trying to help.”24

The Women’s Industrial Home moved to 319 River Valley Road in 1937, where it began taking in orphans and young children whose families were unable to care for them. The numbers grew to such an extent that a Children’s Home was set up, first in a house on Upper Wilkie Road and subsequently a mansion on Pasir Panjang Road to accommodate the larger numbers.25

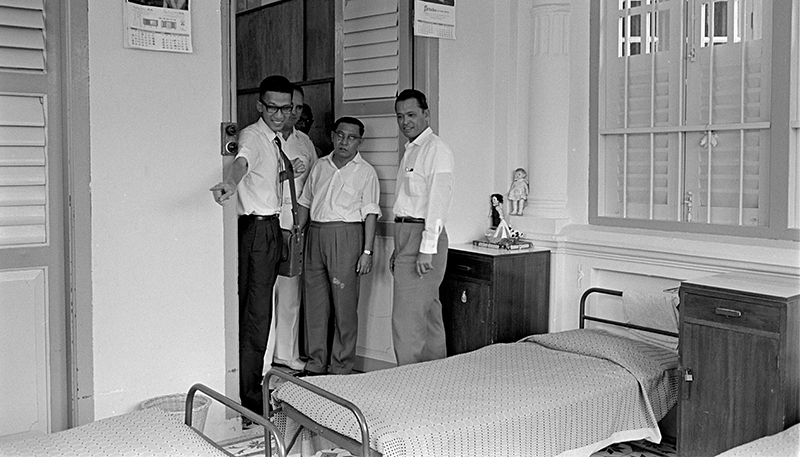

During the Japanese Occupation, one of the temporary premises occupied by the Women’s Industrial Home was 30 Oxley Road, which was next to a Japanese military brothel at 26 Oxley Road.26 The home found a more permanent location at 381 Pasir Panjang Road in 1959. The Army, with help from the Rotary Club, had bought two adjoining houses in 1957 and converted them into a new girls’ home.27

Not all the girls in the Women’s Home were rescued from prostitution or prison. The aforementioned Tan Beng Neo was a young probationary nurse who had run away from home after a violent disagreement with her parents. Seeking help, she went to the Mount Sophia home of the principal of Methodist Girls’ School, Tan’s former school. The principal took Tan to the Women’s Home on Paterson Road.

Tan, a self-taught seamstress, made herself useful at the home by teaching the other residents how to sew. The Army took over the sponsorship of her nurse’s training and paid the $25 for her midwife’s certificate when she completed the course.28

The young women were taught basic English, domestic work, sewing and needlework. And like the boys, jobs were found for them once they became employable as well as marriage partners. To ensure that the young women were not exploited once they left the home, potential employers and marriage partners were thoroughly screened.

Although the colonial government gave the Army subsidies for the homes it ran, the money was never enough and there were regular appeals for donations. The residents in the homes were engaged in making a variety of handicrafts for sale to raise more funds for expenses. However, the iconic Salvation Army Christmas kettle complete with bell ringers, seen in front of malls all over the world to raise money during the Christmas season, was only introduced to Singapore in December 1988.29

Helping Former Prisoners

In 1936, the Army also started working with the Singapore Aftercare Association in the rehabilitation of discharged prisoners and to help them find employment.30 Army officers made prison visits to evangelise. They also identified prisoners in need of a helping hand to reintegrate into society once out of prison and even gave them temporary shelter.

According to the report by Lord, in the first year, “571 interviews had been given to 144 men and women before and after discharge. Of this number, 115 desired the help of the Association, and out of that number eight were repatriated; seven were restored to friends who would look after them, as for various reasons it was not possible to offer them work; 54 were helped to get jobs; and in one case it was made possible for a man to have his previous source of income, which had been forfeited on account of crime, restored to him”.31

In 1938, the Army opened the Discharged Prisoners’ Home on Race Course Road to provide a temporary hostel for those recently released from prison and to tide them over while employment was being found. “The Home will not be a final stopping place for them,” said Lord. “It would fulfil an urgent need, however, as many men coming out did want some place to which they could go for a few days.” The Singapore Aftercare Association bore the rent for the home.32

The War

When the British surrendered Singapore on 15 February 1942, Japanese troops swept through the island, eventually entering the Army’s headquarters at Temple House (now the House of Tan Yeok Nee) at the junction of then Tank Road (now Clemenceau Avenue) and Penang Road.

Tan recalled: “And they [Japanese troops] came into the Salvation Army Headquarters… and Yamashita [Tomoyuki], the General, wanted that place… We were fortunate because… Brigadier Lord and… Major [Chas. F.] Davidson… were able to speak Japanese… So they were able to ask… for certain things: ‘Can we take our things? We need our food and stuff.’… And we managed to get a piece of paper, all written in Japanese.”33

That piece of paper proved invaluable. Tan said: “[W]e pasted it under a glass on the front door [of 30 Oxley Road, its then location of the Women’s industrial Home] and put a piece of wood behind it and nailed it. So that nobody could tear it or take it away. You know, that was a very precious piece of writing whatever it was… And… it was with the stamp of the General [Yamashita]. So nobody dared to come and molest us or do any harm to us… Because whenever the soldiers came in afterwards, we… bowed to them and tried to smile but pointed to the piece of paper on the door… We were very grateful for that piece of paper.”34

The Army headquarters was stacked floor to ceiling with cartons of tinned food and bags of rice that British soldiers and civilians had helped Salvationists salvage from bombed-out warehouses, according to Tan.35 In addition to the paper guaranteeing safe passage, the Salvationists were also given one day to move as much of the food as they could haul to 30 Oxley Road.

During the Japanese Occupation, while male European Salvationists were interned, two European women officers were able to continue their work outside the internment camp for several months before they were taken in.36 Together with the Asian Salvationists like Tan, they were dressed in their white Army uniforms and identified with arm bands issued by the Japanese.

Postwar Recovery

Although lasting less than four years, the Japanese Occupation left Singapore with scores of social issues: poverty, homelessness, hunger, crime, broken families, juvenile delinquency, gambling, opium addiction, and displaced and missing persons.

The organisation of the War Relief Fund brought the interned Army officers quickly back to active duty. They took charge of the entire operation “including investigation and relief distribution, from a relief centre set up in the Victoria Memorial Hall”. The fund was set up when the British Military Administration (BMA) demonetised the currency used during the Japanese Occupation.37

So quickly did the Army work that by October 1945, Colonel Bertha Grey, the first matron of the girls’ home on River Valley Road and the social secretary of the Army, had gotten the homes going again and Salvationists were staffing the People’s Restaurants.38 These “restaurants” scattered in town provided cheap meals for workers amid rising food prices. They had been started by the newly set-up Social Welfare Department established in April 1946 when the BMA ended.

On top of training to be Salvationists, many were also taught to undertake the social work tasks that were part and parcel of their evangelical work. In fact, the Army had been the only agency training social workers until the Department of Social Work was set up in the University of Malaya in 1952. Because Salvationists were among the earliest to receive social work training as part of their evangelical mission, some became the pioneer staff at the new Social Welfare Department.

“Usually, most of the staff that helped the Social Welfare came from the Salvation Army,” said Tan. “You see, there was nothing, nobody was trained. Nobody was able to do the work… The practical part of it [running the homes and providing social services] was all run by most of the Salvation Army officers.”39

In the immediate postwar years, the Army also undertook the arduous process of restoring their war-damaged Temple House headquarters. So named because of its Chinese-style architecture (known today as the House of Tan Yeok Nee), the property had been leased in January 1938 as the Army’s headquarters. A property then of the Church of England, it had once been a residence for girls called St Mary’s Home.40

In 1940, the Army had acquired the place for $50,000 with a loan of $25,000 from the Straits Settlements government and a grant of $25,000 from its London headquarters. The building also became a training centre and accommodation for married officers.41 Restoration took six years, and in 1951, Governor of Singapore Franklin Gimson officially opened the building as The Salvation Army Command Headquarters.42

In 1959, Lord, the officer who had gotten the Salvation Army to such an excellent start in 1935, returned to Singapore for a last visit.43 (After his release from internment at the end of the Japanese Occupation, Lord had returned to duty in Seoul in 1946. Unfortunately, he was captured by the North Koreans at the outbreak of the Korean War (1950–53) and interned until 1953.44) Lord was reported to have been amazed at Singapore’s political development. “I sincerely hope that the building of a new Asia is done on sound principles of democracy, righteousness and political integrity,” he said.45

Lord would have been even more amazed to find out that the Salvation Army headquarters he had purchased in 1940 for $50,000 was sold in 1991 for $20 million.46 That sum was used to finance its new and larger headquarters in Bishan, which opened in 1994.47

Today, the Salvation Army in Singapore runs a host of programmes for children and youth, the elderly, migrant workers, former prisoners and the general community. It runs Gracehaven, a children’s home; the Peacehaven Nursing Home; Carehaven, a shelter for foreign domestic workers; and a few thrift stores around Singapore.

Lee Geok Boi is an editorial consultant and author of several books focusing on aspects of Singapore’s pre- and postwar history. Cookbooks are her special interest.

Lee Geok Boi is an editorial consultant and author of several books focusing on aspects of Singapore’s pre- and postwar history. Cookbooks are her special interest.NOTES

-

“Salvation Army,” Straits Times, 15 March 1935, 13. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Salvation Army Attack on Java,” Straits Budget, 10 March 1898, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Open-air Sermons,” Straits Budget, 5 November 1936, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“General Booth Goes to Japan,” Eastern Daily Mail and Straits Morning Advertiser, 24 November 1906, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“About Us,” The Salvation Army Japan, last accessed 5 September 2023, https://www.salvationarmy.or.jp/english-home/history. ↩

-

“The Salvation Army,” Malayan Saturday Post, 4 December 1926, 15. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Salvation Army Meeting,” Malayan Saturday Post, 4 December 1926, 15. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Salvation Army: Work of Organisation Explained by Head,” Malaya Tribune, 3 December 1926, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Salvation Army: Headquarters Established,” Malaya Tribune, 14 May 1935; 12; “Salvation Army,” Straits Budget, 23 May 1935, 14. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Salvation Army in Singapore,” Straits Budget, 25 April 1935, 8. (From NewspaperSG); Ho Chi Tim and Ann Wee, Social Services (Singapore, Institute of Policy Studies and Straits Times Press, 2016), 34. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 361.95957 HO) ↩

-

“Relief Funds,” Morning Tribune, 12 February 1936; 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Ho and Wee, Social Services, 32. ↩

-

“Local Distress Relief,” Malaya Tribune, 19 February 1936, 9. (From NewspaperSG). The Silver Jubilee Fund Act is still found in the Statutes of Singapore. See “Silver Jubilee Fund (Singapore) Act (Chapter 294),” Singapore Statutes Online, last updated 5 September 2023, https://sso.agc.gov.sg/Act-Rev/SJFSA1936/Published/19870330. ↩

-

“Salvation Army in Y.M.C.A. Hall” Straits Times, 31 October 1936, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“No Spiritual Uplift at the Esplanade,” Straits Budget, 26 August 1954, 12 . (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“‘Army’ Prepares for Esplanade ‘War’,” Straits Times, 6 October 1954, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“New Chance in Life for Destitute Boys,” Straits Times, 29 November 1936, 28. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Salvation Army Boys’ Industrial Home,” Morning Tribune, 2 March 1937, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“How Industrial and Remand Homes Boys are Trained,” Straits Times, 9 October 1938, 6; “Saving Young Boys from Prison,” Straits Times, 9 October 1938, 32. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

How Salvation Army Home Helps Destitute Women,” Straits Times, 10 May 1940, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“New Home for Women in Singapore,” Pinang Gazette and Straits Chronicle, 16 December 1935, 10; “Freedom from Influence of Social Evils,” Pinang Gazette and Straits Chronicle, 27 November 1936, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Rescue Work Among Girls,” Straits Times, 13 February 1941, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Tan Beng Neo, oral history interview by Liana Tan, 31 March 1984, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 7 of 26, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000371), 100. ↩

-

“Salvation Army to Open New Children’s Home,” Straits Times, 15 January 1939, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Tan Beng Neo, oral history interview by Liana Tan, 10 April 1984, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 13 of 26, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000371), 100. ↩

-

“Salvation Army to Have New Home,” Straits Times, 8 November 1957, 5; “Salvation Army’s New Home,” Singapore Standard, 17 June 1958, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Tan Beng Neo, oral history interview, 3 December 1983, Reel/Disc 5 of 26, 66, 68; Tan Beng Neo, oral history interview, 3 December 1983, Reel/Disc 6 of 26, 77. ↩

-

“Kettle of Funds,” Straits Times, 20 December 1988, 18. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Donations Needed,” Straits Times, 28 March 1936, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Helping Hand for Local Ex-prisoners,” Straits Times, 16 April 1937, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“New Home for Discharged Prisoners,” Straits Times, 24 July 1938, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Tan Beng Neo, oral history interview, 4 April 1984, Reel/Disc 10 of 26, 135. ↩

-

Tan Beng Neo, oral history interview, 4 April 1984, Reel/Disc 10 of 26, 137. ↩

-

Tan Beng Neo, oral history interview, 4 April 1984, Reel/Disc 10 of 26, 143. ↩

-

Tan Beng Neo, oral history interview, 4 April 1984, Reel/Disc 12 of 26, 25:14 mins. ↩

-

Ho and Wee, Social Services, 45. ↩

-

Tan Beng Neo, oral history interview, 17 April 1984, Reel /Disc 17 of 26, 250. ↩

-

Tan Beng Neo, oral history interview, 24 April 1984, Reel/Disc 21 of 26, 316. ↩

-

“Temple House to Be Headquarters of Salvation Army,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 15 January 1938, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Salvation Army to Buy Old Chinese House,” Straits Budget, 14 March 1940, 17. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The House of Tan Yeok Nee,” Straits Times, 16 March 1983, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Salvation Leader Lord Is Surprised,” Straits Budget, 13 May 1959, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Mrs Lord Knew He Would Return,” Straits Times, 22 April 1953. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Salvation Army HQ Sold to Cockpit for $20m,” Straits Times, 20 April 1991, 20. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“A New Headquarters at Bishan,” Straits Times, 20 January 1994, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩