The 1973 SEAP Games in Singapore

The 7th South East Asian Peninsular Games marked the first time that Singapore hosted an international sporting event since gaining independence in 1965.

By Lim Tin Seng

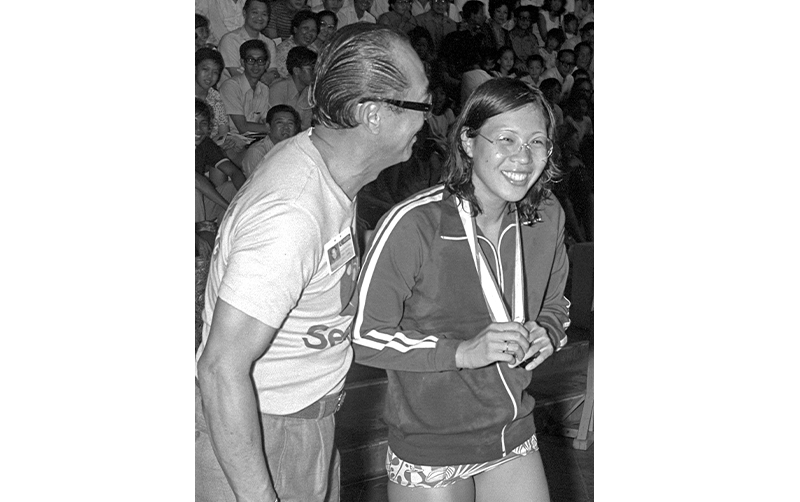

It was September 1973 and the stakes were high for Singapore, and for Singapore’s “Golden Girl” Patricia Chan. It was the 7th Southeast Asian Peninsular (SEAP) Games, the precursor to today’s Southeast Asian Games, and the event was being held in Singapore for the first time.

One of the biggest international sporting events to be hosted by Singapore since becoming independent, it was a matter of pride for the young nation. There was a desire to show, not only that the country was able to host an event like this, but that it would also do well in the medal tally. For the latter, all eyes were on Singapore’s star athletes, and in particular swimming sensation Pat Chan.

Chan’s haul of 33 gold medals from the previous four SEAP Games – an average of eight golds per event – meant that much of the nation’s hopes would rest on her young shoulders. However, the 1973 games were going to be a different kettle of fish for the 19-year-old. To improve her physical fitness ahead of the games, Chan had plunged into her training, determined to work extra hard. However, in this case, working hard turned out to be counterproductive as she ended up tearing “the muscle on my back, my shoulder blade… So it was very difficult. It wasn’t a bad tear but it was very, very painful. Every stroke hurts. And this was two weeks before the competition”.1

Fortunately for Chan, and for Singapore, all went well. Chan managed to snag six gold medals and Singapore secured a remarkable second place in the overall medal tally, just behind Thailand.

The nation also acquitted itself well to the watching world. The newly built National Stadium was a fitting venue for the opening and closing ceremonies, while other stadiums around Singapore helped to host some of the events. Interestingly, the games also cleverly leveraged the newly built housing estate of Toa Payoh. The games village used Housing and Development Board (HDB) apartment blocks in Toa Payoh to house officials and athletes, while the nearby Toa Payoh Sports Complex was the venue for swimming events and athletics. Even the building housing the secretariat found a new and important life post-games.

A New Stadium for the Games

Singapore had originally been invited by the SEAP Games Federation Council to host an earlier edition of the games. However, they were turned down as Singapore felt that it did not have the facilities, particularly a national stadium, to embark on such a venture. “Until then, we are not ready for anything,” said President of the Singapore Olympic and Sports Council Othman Wok when he announced in 1967 that Singapore would not be able to host the 5th SEAP Games.2

Getting a proper stadium was thus the first job at hand. Located on the grounds of the former Kallang Airport and Kallang Park, the stadium took six years to build, from December 1966 to June 1972. It boasted a distinct Brutalist design, adorned with a stunning array of monumental columns and heroic diagonal beams, complemented by expansive rake-seating terraces. The megastructure also featured four imposing floodlights and a daring 20-metre-high cantilevered roof that gracefully extended over the grandstand.3

The National Stadium was officially declared opened by Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew on 21 July 1973, just two months before the SEAP games. At the opening, Lee noted that the $50-million stadium would not be profitable. “In fact, we shall be lucky to get enough receipts to pay for the annual administrative and maintenance costs,” he said. “However, as a social investment, fully and properly used, it can be made a great asset… people will be encouraged to watch, and then to personally take part in sporting activities.”4

Toa Payoh Games Village

Just as important as the sporting venues were the ancillary facilities such as the games secretariat and the Games Village. Instead of purpose-built housing or student dorms, the 1,500 competitors and officials were housed in four newly completed 25-storey-high HDB apartment blocks in Toa Payoh, each with 96 units.5

The housing estate was chosen as the Games Village because the flats were “ideally located and surrounded by all the necessary facilities and amenities” such as a new swimming complex with five pools and a sports complex with a 400-metre running track. Athletes could also avail themselves of the nearby cinemas, an emporium, 180 shops, a supermarket, a post office, a bus terminal, a hawker centre and a medical centre.6

“For the first time competitors will be housed in high rise flats and this will be a change for SEAP Games athletes who have lived in makeshift two-storey apartments and students’ hostels,” said E.W. Barker, president of the Singapore National Olympic Council, and Othman Wok.7

Each flat – with three bedrooms and a hall – was shared by six athletes and furnished with the “amenities of a luxurious hotel room”.8 The Games Village received a thumbs-up from athletes. “The organisers have done a wonderful job in providing first class accommodation,” said Singapore veteran hurdler Osman Merican. “What surprised me was the gang of women workers marching into our rooms in the mornings and tidying our beds and mopping up the caterers [sic]. This is something I have not experienced in other international games”.9

The SEAP Games Village was declared open by Deputy Prime Minister Goh Keng Swee on 30 August 1973. To mark the occasion, Goh planted a hop tree in the village centre while the heads of the contingents from the other participating countries also planted their own trees. Goh noted: “[A]s you can see for yourself, and as the tree-planting ceremony is intended to symbolise, this satellite town is not really a concrete jungle.”10 (After the games, the flats were sold through a balloting exercise at $19,000 each, with an additional $1,700 for furnishings.)

The secretariat for the games was a three-storey building that was also in Toa Payoh. After the games, it became the Toa Payoh Branch Library, which opened on 7 February 1974.11

Let the Games Begin

The opening ceremony of the 7th SEAP Games on 1 September 1973 was described as the “most colourful” ceremony Singapore had ever witnessed at the time. Shown live on television, the ceremony commenced with the arrival of the president of Singapore, Benjamin Sheares, followed by the singing of the National Anthem and the introduction of the athletes from the seven participating nations – Burma (now Myanmar), Khmer Republic (now Cambodia), Laos, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand and South Vietnam.12

In their striking crimson jackets for male athletes and cream for female, the Singapore contingent emerged onto the running track where they were greeted by the frenzied cheers of an enthusiastic crowd of 50,000 spectators.

The Singapore contingent was 454 athletes strong, and included swimming sensations Pat Chan and Elaine Sng, track stars Heather Merican and Glory Barnabas, high jumper Noor Azhar Abdul Hamid, and judokas Tan Sin Aun, Wong Kin Jong and Kan Kwok Toh.13

After Barker’s welcome speech, President Sheares officially declared the games open. The blue-and-white SEAP Games flag was unfurled amid the “ringing sound of a trumpet fanfare”, and accompanied by the release of some 19,000 multihued balloons and a 21-gun salute.

The theme song was performed by the 2,000-strong Combined Schools Choir as Singaporean sprinter C. Kunalan, dressed in an all-white track suit, carried the SEAP flame into the stadium to light the torch perched at the highest point of the stadium.14 (David Lim Kim San, a music inspector from the Ministry of Education, composed “The SEAP Games Theme Song”, with lyrics by E.W. Jesudason, principal of Raffles Institution.15)

In a solemn tone, swimmer Pat Chan took the SEAP oath on behalf of all participating athletes, pledging their commitment to “take part in the Games in fair competition, respecting the regulations which govern them, and with the desire to participate in the true spirit of sportsmanship for the honour of our country and the glory of sport”.16

Gunning for Glory

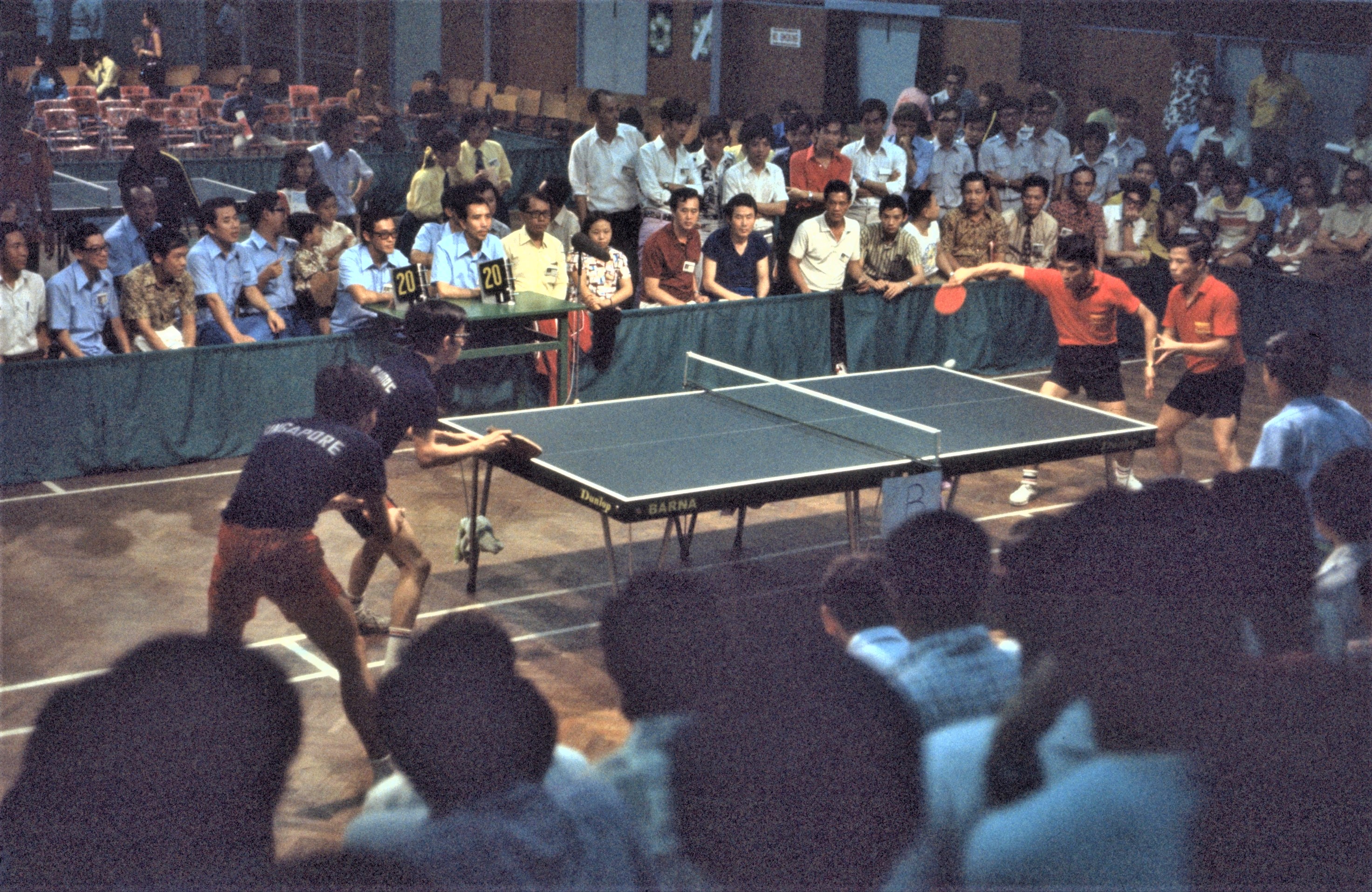

The games featured a total of 16 sporting events: track and field, badminton, basketball, boxing, cycling, football, hockey, judo, sepak takraw, tennis, shooting, swimming, table tennis, volleyball, weightlifting and sailing. These were held at the National Stadium and various other venues, including Chung Cheng High School, Chung Hwa Girls’ School, Farrer Park Athletic Centre, Sembawang Circuit, Gay World Stadium, Jalan Besar Stadium, Katong Grange Hotel, National Junior College, Rifle Range at Mount Vernon, People’s Theatre, Queenstown Reserve Unit Base, Singapore Badminton Stadium and Toa Payoh Swimming Complex.

There was, of course, tremendous pressure on the local athletes. “Singapore expects you to win as many medals as possible,” said Barker at a meeting with the athletes on 27 August 1973. “Never before have we held the SEAP Games in Singapore. We have built a National Stadium, a games village, a new swimming pool and facilities at other venues… The stage is set for the Games and I hope you are ready to do your part.”17

Sprinter Glory Barnabas recalled the demanding training regime of the Singapore track and field team. “We [were] training really very hard, trying to do well for Singapore because this [was] the first time Singapore [was] organising such a big event and [it was] on home ground,” said the former schoolteacher.18

There was a sense of camaraderie though, she said. “[W]e stayed there [at the Toa Payoh Games Village] as a team, we had breakfast together, we had lunch together, and we trained together and had dinner together and we talked shop… I think all these kind of prepared the stage for the games.”

In the end, Singapore ended up with an impressive haul of 45 gold medals, 50 silvers and 45 bronzes. A significant portion of the gold medals came from the swimmers, who amassed 23 golds, 16 silvers and nine bronzes. Along the way, they shattered 19 new SEAP Games records and one Asian Games record.19

Apart from Chan, fellow swimmer Elaine Sng also contributed to the medal haul. She obtained five golds, and set three new SEAP Games records and a new Asian Games record in the 400-metre freestyle.20

Singapore’s first gold medal, however, came courtesy of Heather Merican who triumphed in the women’s 100-metre hurdles and broke the SEAP Games record at the same time. Another standout performer was Barnabas, who claimed victory in the 200-metre sprint. Noor Azhar Abdul Hamid managed to clear an exceptional 2.12 m in the high jump, also setting new Asian Games, SEAP Games and national records. (In fact, his local record would be unbroken for 22 years.)21 The water polo team also contributed to Singapore’s medal tally by clinching the gold medal, while the sailors took home three gold medals and the judokas captured four golds.22

Among the notable winners was table tennis player Chia Choon Boon, who juggled both his training and his work as a Nanyang Siang Pau reporter. After training sessions ended, while his teammates were resting, he would rush out a journal entry for the newspaper about life in the Games Village every day. “I could call the newspaper to tell them what was happening in the Games Village, but… it would be more interesting for the reader to read about things from my perspective.”23 Chia’s moonlighting did not stop him from winning two gold medals for Singapore in table tennis.

A Glorious Finish

After a gruelling week that saw victories, disappointments as well as new records being broken, the games drew to a close on 8 September 1973. “I feel sure that the contestants, both men and women, will continue to be dedicated and even more determined in the future to raise standards even higher,” said Barker in his closing address. “This enthusiasm trend will help SEAP athletes to do well when they compete in other international meets such as the Asian Games.”24

Barker also said that it had been a privilege for Singapore “to have been able to host both athletics and officials from the participating countries”. “I hope that the friendships generated, not only at the various Games venues but also at the Village, have consolidated during the past week,” he said. “I trust that all our guests will take home with them pleasant memories of the cordial ties that they have established in Singapore.”25

As President Sheares solemnly declared the games closed, buglers sounded the Last Post and the SEAP Games flag was lowered. A hushed silence descended as the SEAP flame, which had burnt brightly throughout the event, was gently extinguished. Barker handed the flag to the Thai delegation, whose nation was slated to host the next SEAP Games in 1975.26 Then, breaking the silence, the 1,000-strong choir filled the air with “Auld Lang Syne”, followed by joyous celebrations as the 1,500 athletes let loose in uninhibited delight.

Leaving a Legacy

The 7th SEAP Games held in Singapore left a lasting legacy that went beyond the realm of sports. The games showcased Singapore’s ambition to become a leading sporting nation in the region and demonstrated the nation’s ability to successfully host major international events. Indeed, after the games, the National Stadium continued to be used for various sporting and non-sporting events before it was closed in 2007 and replaced by the current National Stadium.27

While the athletes would always have the memory of participating in the games, for the rest of Singapore, they could own commemorative merchandise such as apparel, pewter medallions and even collectible matchboxes.28

The Board of Commissioners of Currency issued a $5 silver commemorative coin, sold at $6 each, while the Singapore Mint released a set of SEAP Games First Day Cover comprising six stamps – each set costing $15 – in denominations of 10 cents, 15 cents, 25 cents, 35 cents, 50 cents and $1.29 These were very well received, both in Singapore and overseas, and were immediately snapped up.30 All these have since become collectors’ items.

Over time, the SEAP Games themselves have changed. In 1977, the SEAP Games were renamed Southeast Asian Games (SEA Games) to mark the inclusion of Brunei, Indonesia and the Philippines.31 This has since been expanded further and in the 2023 SEA Games, which were held in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 11 countries took part. Singapore has hosted a total of four SEAP/SEA games thus far, in 1973, 1983, 1993 and most recently in 2015. It is next expected to host the event again in 2029.

Lim Tin Seng is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. He is the co-editor of Roots: Tracing Family Histories – A Resource Guide (2013), Harmony and Development: ASEAN-China Relations (2009) and China’s New Social Policy: Initiatives for a Harmonious Society (2010). He writes regularly for BiblioAsia.

Lim Tin Seng is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. He is the co-editor of Roots: Tracing Family Histories – A Resource Guide (2013), Harmony and Development: ASEAN-China Relations (2009) and China’s New Social Policy: Initiatives for a Harmonious Society (2010). He writes regularly for BiblioAsia.ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

7th SEAP Games Programme: Singapore 1st to 8th September 1973 (Singapore : n.p., 1973) (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 796 .0959 SEV)

7th SEAP Games, Singapore, 1973: Bulletin (Singapore: Produced by the 7th SEAP Games Organising Committee in Co-operation with the Singapore Tourist Promotion Board, 1973). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 796 SOU)

7th SEAP Games: Information on Events (Singapore: South East Asia Peninsula Games, 1973). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 796 SOU)

Radio and Television Singapore, “E.W. Barker At Opening of Seventh South East Asia Peninsula Games (SEAP) Games,” 1 September 1973, sound recording, 53:08. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. 1998007702)

Radio and Television Singapore, “E.W. Barker At Opening of Seventh South East Asia Peninsula Games (SEAP) Games,” 1 September 1973, sound recording, 1:03:45. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. 1998007703)

Radio and Television Singapore, “E.W. Barker At Opening of Seventh South East Asia Peninsula Games (SEAP) Games,” 1 September 1973, sound recording, 1:06:10. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. 1998007704)

Radio and Television Singapore, 7th SEAP Games Singapore 1973 Opening Ceremony, video, 1:18:00 (Singapore: RTS, [1973]: MediaCorp Studios, [distributor], 2005). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 796.0959 SEV)

Radio and Television Singapore, “7th SEAP Games Closing Ceremony,” 8 September 1973, sound recording, 30:19. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. 1997002644)

Radio and Television Singapore, 7th SEAP Games Singapore 1973 Closing Ceremony, video, 30:28 (Singapore: RTS, [1973]: MediaCorp Studios, [distributor], 2005). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 796.0959 SEV)

Singapore Broadcasting Corporation, “7th SEAP Games Singapore 1973,” 30 August 1973, video, 1:17:01. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. 1997002643)

NOTES

-

Patricia Chan Li Yin, oral history interview by Denise Ng Hui Lin, 18 March 2015, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 17 of 18, 226, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 002629) ↩

-

Ernest Frida, “S’pore Will Not Bid for 1967 Games,” Straits Times, 9 December 1965, 23; Ernest Frida, “Wok: Wait Until 1972…,” Straits Times, 15 September 1967, 21; “‘Stage the Games in 1971’ Appeal to S’pore,” Straits Times, 7 December, 1969, 23. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

To Commemorate the Opening of the National Stadium, Republic of Singapore: 1973 (Singapore: National Stadium, 1973), 5–7. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 796.0685957 TO) ↩

-

Lee Kuan Yew, “The Official Opening of the National Stadium,” speech, National Stadium, 21 July 1973, transcript, Ministry of Culture. (From National Archives of Singapore document no. lky19730721) ↩

-

“Toa Payoh Is Games village,” Straits Times, 21 January 1972, 24. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Minjoot Named Village Head,” Straits Times, 4 August 1973, 23. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Ernest Frida, “On Schedule – Work on Seap Projects,” Straits Times, 24 July 1972, 27. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Games Village Will Be Like Luxury Hotels,” Straits Times, 9 June 1972, 27 (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Ernest Frida, “Athletes Happy in Seap Village,” Straits Times, 8 August 1973, 22. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Dr Goh Opens Games Village,” Straits Times, 31 August 1973, 24. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Call for Sale of ‘Instant Live-in’ Flats,” Straits Times, 24 October 1973, 7; “Jek to Open Toa Payoh Library,” Straits Times, 5 February, 1974, 13. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Chandran, “Sheares Opens SEAP Games.” ↩

-

Jeffrey Low, “The ‘Golden Hopefuls…,” New Nation, 21 August 1973, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Chandran, “Sheares Opens SEAP Games”; Mediacorp Pte Ltd., “7th SEAP Games Singapore 1973,” 30 August 1973, audiovisual, 30:00. (From National Archives of Singapore accession no. 1997002643) ↩

-

“SEAP Games Theme Song Picked,” New Nation, 13 April 1973, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Chandran, “Sheares Opens SEAP Games”; Mediacorp Pte Ltd., “7th SEAP Games Singapore 1973,” 33:20. ↩

-

Ernest Frida, “Barker Tells Our Team: Win Medals,” Straits Times, 29 August 1973, 23. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Glory Barnabas, oral history interview by Ghalpanah Thanagaraju, 11 October 2002, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 5 of 9, 106–7, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 002712) ↩

-

Singapore Sports Council, Annual Report 1973 (Singapore: Singapore Sports Council, 1974), 11 (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 354.5957093 SSCAR); Albert Johnson, “Elaine Sets Her Sights on Teheran,” Straits Times, 11 September 1973, 22; Albert Johnson, “Golden Harvest By Our Swimmers,” Straits Times, 6 September 1973, 24. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Tony Francis, “I Want To Catch Up on What I’ve Been Missing: Pat,” Straits Times, 9 September 1973, 24 (From NewspaperSG); Percy Seneviratne, Golden Moments: The S.E.A games 1959–1991 (Singapore: P. Seneviratne, 1993), 46. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 796.0959 SEN) ↩

-

“Great Sports,” Straits Times, 10 September 1973, 8; “Heather Wins Our First Goal,” Straits Times, 3 September 1973, 1; Ernest Frida, “Glorious Glory Wins 200m in Photo Finish,” Straits Times, 5 September 1973, 1 (From NewspaperSG); Seneviratne, Golden Moments, 46. ↩

-

“Water-polo Gold Due to Team’s Fitness,” New Nation, 6 September 1973, 11; Peter Siow, “Chong Boon Achieves His Ambition,” Straits Times, 6 September 1973, 22; Jeffrey Low, “1973: Only Seap Made It a Good Year…,” New Nation, 29 December 1973, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Chia Chong Boon, oral history interview by Madeline Ang, 21 January 2014, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 9 of 18, 175–76, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 003847) ↩

-

E.W. Barker, “The Closing Ceremony of SEAP Games,” speech, National Stadium, 8 September 1973, transcript, Ministry of Culture. (From National Archives of Singapore document no. PressR19730908b) ↩

-

Barker, “The Closing Ceremony of SEAP Games.” ↩

-

Fong, “In the Best SEAP Spirit.” ↩

-

Shree Ann Mathavan, “Goodbye to a Grand Old Dame,” New Paper, 10 August 2006, 16; “And Jacko Was There Too,” New Paper, 28 September 2010, 41. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Medallion to Mark SEAP Games in S’pore,” Straits Times, 29 August 1973, 17. (From NewspaperSG). ↩

-

“Silver Fivers on Sale From Monday,” Straits Times, 7 July 1973, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“6,000 Orders for Silver Fivers,” Straits Times, 13 June 1973, 21; “All Seap Games Coins Sold Out,” Straits Times, 14 September 1973, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Gerald Wong, “Team S’pore Way to Sports Glory,” Straits Times, 21 April 2001, 6; Serene Luo, “The SEA Journey,” Straits Times, 6 February 2012, 20. (From NewspaperSG) ↩