Konfrontasi: Singapore’s Experience of an Undeclared War

Opposing the formation of the Federation of Malaysia, Indonesia waged a three-year armed conflict against Malaysia and Singapore.

By Alvin Tan

It was late in the night of 9 December 1963 when the Indonesian Confrontation, or Konfrontasi, claimed its first victims in Singapore. It happened on Jalan Wangi in Sennett Estate, a quiet neighbourhood close to Potong Pasir.

At around 10.45 pm, Mohamed Kassim Ismail and Chadar Mastan Abdul Aziz, operators of a cigarette and sundries stall, had gone to investigate a suspicious blue Ford Consul when an explosion ripped through the night air, instantly killing them both.

The blast left a crater 2 m across and 1 m deep, and blew a brick wall apart. It also threw the car chassis 15 m away and shattered windows about 270 m away.1

Bomb Blast at Sennett Estate

This was not the first effort by Indonesian saboteurs to target Singapore. It was, in fact, the fourth such attack. There had been three relatively smaller blasts at Katong Park on 24 September, 26 September and 6 October earlier that year, but those explosions did not cause fatalities and the media was mystified as to the motives of the bombers. The deaths of the two men made it clear, however, that the bombings were “part of an organised campaign of terror” involving a “bomber, mad or sane” who “knows a great deal about explosives”.2

Following this blast, security measures at key installations were stepped up and an islandwide manhunt operation commenced.3 On 20 December, 19-year-old Shairy Aman, alias Hitam, was arrested at Queen’s Theatre in Geylang, and 10 days later, Amat Junit, alias Ahmad Toh, 20, was picked up at Kampong Amber.4

On 16 April 1964, Shairy and Amat revealed in court that they, together with their handler Nordin Lemon, and another man, had initially intended to bomb more strategic targets. On 8 December 1963, the four set out in a car to plant explosives in two locations: Shairy had gotten off at Bukit Timah to blow up water pipes, while the other three drove on to Bukit Timah Railway Station. “Our intention in going to the station was to blow up the rail tracks,” said Nordin. However, both missions were aborted. Shairy admitted that “he had been afraid to explode the bomb” at the water pipes, while there were police officers at the railway station. The next day, Amat suggested to Shairy to “go and explode the bomb” at Sennett Estate.5

Arriving at the targeted site, Amat planted the bomb under the Ford Consul in a lane behind a row of shophouses and lit the fuse with a lighted cigarette. Soon after they had driven off, the bomb exploded. The men had been told that “if they could not achieve their specified objectives they were to leave the explosives where their detonation would create alarm by their indiscriminate damage”. Some 20 to 25 pounds of explosives were used in the Sennett Estate blast.6

The two men who died had been watching a TV programme in a radio shop before returning to their nearby cigarette and sundries stall. At some point, they might have “heard a sizzling noise or [had] seen a short length of burning fuse under a blue Ford Consul” and paid for it dearly. The bodies of the two men, badly mangled, were found in a garage about 6 m away.7

Reasons for Konfrontasi

Today, many people in Singapore remember the 1965 MacDonald House bombing when they think of Konfrontasi. However, the MacDonald House bombing was only one of many such incidents during the period of Konfrontasi, which began in 1963 and officially lasted until 1966. The bombings claimed the lives of at least seven people.

Konfrontasi was a policy by Indonesia under President Sukarno (1950–67) to combat what he claimed was neo-imperialism. In January 1963, Indonesian Foreign Minister Subandrio declared that Indonesia could not but “adopt a policy of confrontation against Malaya because at present they represent themselves as accomplices of the neo-colonialists and neo-imperialists pursuing a hostile policy towards Indonesia”.8

Sukarno was convinced that the Federation of Malaysia, formed on 16 September 1963,9 was a neo-colonial imperialist plot (dubbed “Nekolim”) designed to secure, ensure and perpetuate British dominance in the region. Seeing the British as both a threat and an obstacle to Indonesia’s regional ambitions and influence, Sukarno used Konfrontasi as a tool to destabilise Malaysia, frustrate its success and to rally Indonesians around him. In the face of real or supposed threats from foreign powers, Konfrontasi united Indonesia’s diverse peoples and established Sukarno as “the most important political force in Indonesia”, to the detriment of his political opponents.10

After the United Nations released its report in September 1963 on its mission to survey the people in North Borneo (Sabah) and Sarawak over the merger, relations between Malaya and Indonesia reached an inflexion point.11 On 15 September 1963, Indonesia rejected the report’s findings and refused to recognise Malaysia, which was proclaimed the following day. On 17 September, Malaysia broke off diplomatic relations. Four days later, Indonesia retaliated by severing its diplomatic and commercial ties with Malaysia and Singapore. On 25 September, Sukarno declared that he would “gobble Malaysia raw” or “Ganyang Malaysia”.12

Sukarno’s low-intensity war, which encompassed both overt and covert warfare, eventually morphed into a campaign of terror and sabotage involving trained Indonesian commandos, saboteurs, agents and local sympathisers.13 Fought in the jungles of Borneo along Indonesia’s extensive and porous border with Sabah and Sarawak, and in towns and cities such as Singapore, Penang and Kuala Lumpur, Konfrontasi involved 54,000 British and Commonwealth troops and scores of policemen and volunteers.14 Though the numbers of civilian casualties were relatively low, Konfrontasi nonetheless underscored the impact that an asymmetrical campaign of terror could exact in an urban setting like Singapore.

Acts of Terror

The first attacks in Singapore took place at the popular sea-facing Katong Park, frequented by families and courting couples.15 On 24 September 1963, a bomb blast in the park shattered the windows of the Ambassador Hotel across the road, about 35 m away. Evidence recovered from the scene indicated that a home-made explosive device was used. Two days later, on 26 September, a second bomb was detonated 20 m from the site of the first blast, “scaring away children from the park”.16

By the third blast on 6 October, which took place 60 feet from the earlier blasts, the police admitted that they were “baffled”. This time, a black Mayflower car belonging to Low Poh Lin – a 38-year-old lifeguard who worked at the park – was destroyed. Describing the blast, Low said: “I heard an explosion. When I ran out, I saw my car on fire.” He later “told police that he has no enemies, who would want to blow up his car”.17

By now, jittery Katong residents were anxiously wondering when the “mad bomber” would “strike again and where he would plant his next bomb”. The Criminal Investigation Department took over the investigation and, in the absence of clear leads, a $3,000 reward was offered.18

In 1964 alone, 18 explosions swept through Singapore and encompassed targets like the Merdeka Bridge and the iconic Raffles Hotel. On 8 March, a time bomb was planted in a drainpipe along Bras Basah Road outside Raffles Hotel that went off at 11:40 pm. “I first thought it was the firing of crackers. Almost simultaneously, a chair cushion from nearby hit me in the face with a powerful impact. I was unhurt but I knew then that it was some frightful explosion,” said an American tourist who was staying in one of the rooms.19

On 27 March, a bomb exploded outside the perimeter fence of the Istana, near the Bukit Timah filter works, damaging some 4 m of the fence and shattering window panes within a 350-metre radius. Two people were killed and six were injured when a bomb went off on 12 April at 8:05 pm at a block of Housing and Development Board flats on Jalan Rebong, off Changi Road. The victims – Aishah Bee Abdullah, 50, and her 16-year-old daughter Sharifon, a student at Tanjong Katong Girls’ School – were watching television in a wooden house 9 m away when the blast killed them.20

On 23 May and 21 July, Indonesian saboteurs attempted to blow up Merdeka Bridge. The bridge suffered only slight damage but police, in response to the second blast, “said that the obvious intention was to blow a hole through the bridge”.21

The bombing of MacDonald House, however, was the deadliest and most well-known attack. At 3.07 pm on 10 March 1965, a bomb exploded at the 10-storey building on Orchard Road – then one of the tallest in Singapore and the first fully air-conditioned office building in Singapore and Southeast Asia.22 The bomb, which had been placed on the mezzanine floor near the lift, injured at least 33 people and claimed three casualties: Suzie Choo, 36, the private secretary to the manager of Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank, and Juliet Goh, 32, a filing clerk at the bank, died on the spot. Mohammed Yasin Kesit, 43, a driver for the Malaya Borneo Building Society, died a few days later. “Many others – in the bank and on the road – fell like ninepins, many seriously injured. Every window within a hundred yards was shattered and almost every car outside the building and across the road was damaged,” reported the Straits Times.23

Two Indonesian commandos, Osman Haji Mohamed Ali, 25, and Harun Said, 21, were arrested and charged in court. They were sentenced to death on 20 October 1965, and their execution by hanging on 17 October 1968 would cast a pall over relations between Singapore and Indonesia in the years to come.24

Combating Konfrontasi

Given the scale and nature of the Indonesian threat, the politics of the Cold War and as Malaysia’s strongest ally, the United Kingdom rotated its forces through Singapore between 1963 and 1966. It was the UK’s greatest show of force since World War II.25 The Royal Air Force also dispatched four to eight nuclear-capable V-Bombers through Tengah and Butterworth airbases in case things escalated.26 Deploying from Singapore, submarines from the Royal Navy’s 7th Submarine Division conducted undersea operations.27

This was not overkill. As historians Peter Hennessy and James Jinks described in their book, The Silent Deep, “The Indonesians operated vast amounts of Soviet equipment, including a ‘Sverdlov’ class cruiser, several ‘Skory’ destroyers and significant numbers of MIG-15s, -17s, -19s and 21s [aircraft]. The Indonesian Navy also possessed one of the most powerful submarine forces in the Asia-Pacific region, consisting of twelve Soviet-built ‘Whisky’ class submarines, two torpedo retrievers and one submarine tender.”28 In short, the military threat from Indonesia was not something that could be dismissed.

Confronted with the crushing threats in a domestic political environment in which opposition and contestation were the norm, the Singapore government acted quickly to nullify the security threats, cushion the economic fallout, and educate the public about the threats the country was facing.

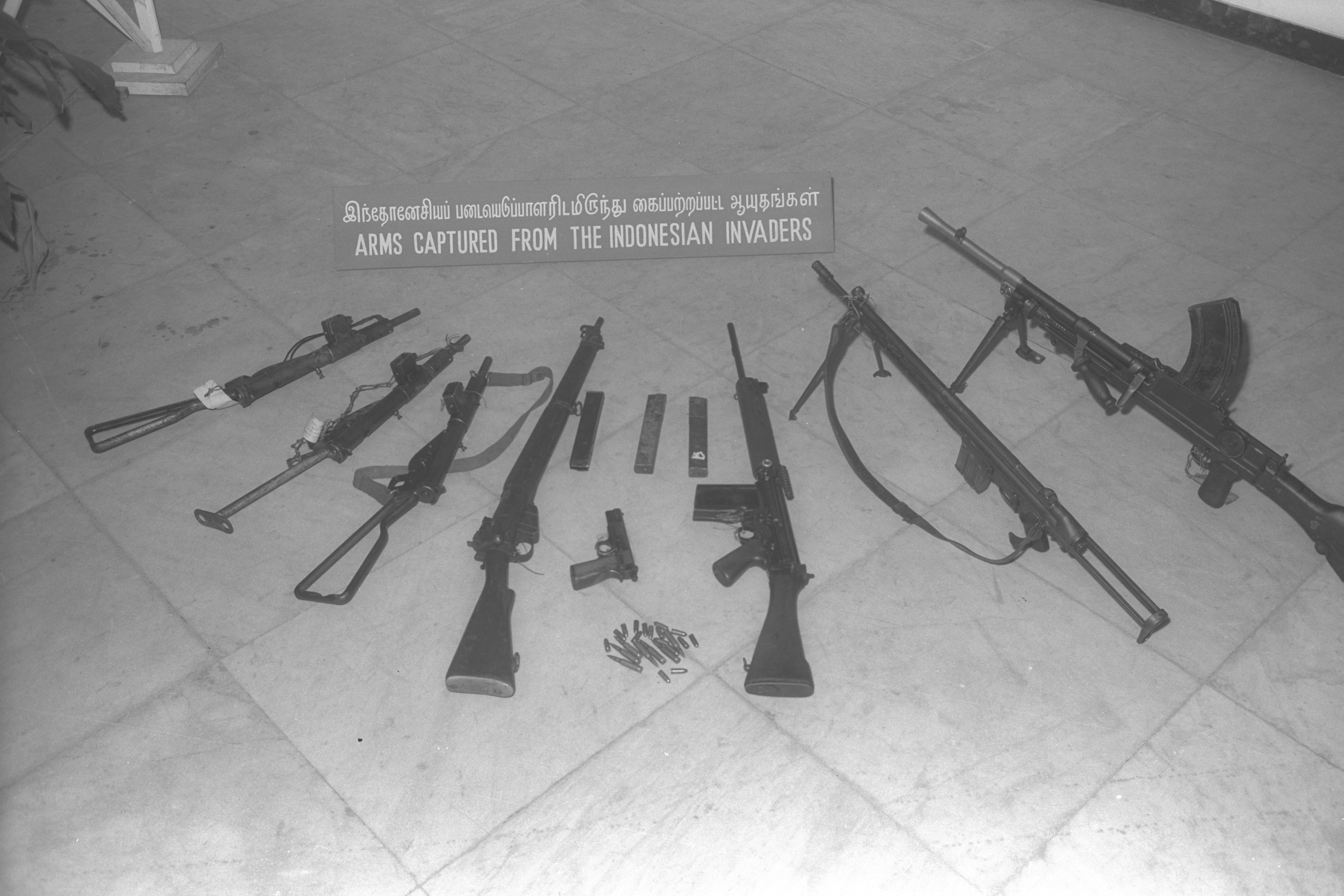

Security operations were crucial in uncovering Indonesian saboteurs and their munitions caches, and in foiling their plans. In December 1963 alone, 24 subversives were detained in Singapore as part of Operation Mara launched by the Malaysian police. The intelligence gleaned from this operation in turn led to the discovery of munitions caches all over Singapore. Packages containing explosives and fuses were found at Kampong Amber and near the residence of the chief justice on Nassim Road – all primed and ready to be detonated. At Jalan Eunos, an earthen jar containing 25 hand grenades, three Sten guns and six Sten magazines was uncovered. A cache of four Sten guns, two Luger pistols, explosives and demolition equipment were recovered at Wing Loong Estate.29 Such discoveries and seizures became commonplace throughout Konfrontasi as were bomb hoaxes and bomb scares.

As the number of bomb blasts mounted in early 1964, the government enrolled volunteers for the newly mustered Vigilante Corps (VC) on 23 April 1964. The VC was tasked to guard against Indonesian saboteurs and infiltrators, protect vital installations and patrol crowded public areas. In less than a month, 14,022 people had signed up. Having been put through the paces on the intricacies of the law, first aid and unarmed combat, the first 10,000 VC volunteers were deployed on 16 June 1964. Once a week, these volunteers went on three-hour patrol in small teams at night, securing their neighbourhoods. Although lightly armed and equipped with just staves, flashlights and a VC armband, their presence provided a visible deterrent and sense of security.30

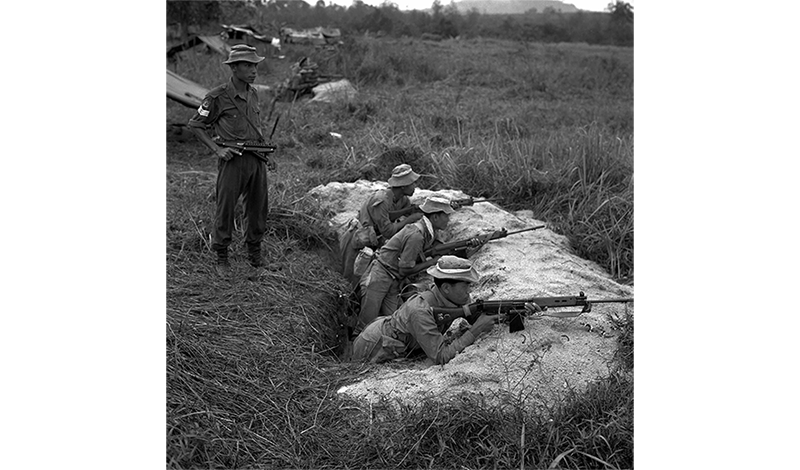

Singapore also sent troops to Peninsular Malaysia and Borneo. Its small army – comprising 1st and 2nd Battalions, Singapore Infantry Regiment (1 SIR and 2 SIR) – was fully deployed in combat operations. Eight soldiers from 2 SIR were killed and five injured when they were ambushed by Indonesian infiltrators on 28 February 1965 during a deployment 20 miles inland from the Kota Tinggi coast.31 In the aftermath, a large-scale operation was mounted to hunt down and eliminate the infiltrators.

When the operation ended six weeks later in April, 37 Indonesian infiltrators had been killed and at least 33 captured, many by the men of 2 SIR who acquitted themselves with distinction.32 On 5 May 1965, Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew paid tribute to the soldiers for “excelling” in operations against Indonesian guerrillas in Sabah and Johor. “You have carried the name of Singapore very high among the States of Malaysia,” he told some 300 men of the regiment at a reception at Sri Temasek to congratulate them on their success. “Your operations in Sabah and Johore proved that city life did not make you less rugged than rural folks,” he added.33

Disruption to Trade

Konfrontasi also had an adverse effect on trade and economy. Singapore’s trade with Indonesia plunged by almost 24 percent in 1964.34 For workers in industries and trades that depended heavily on Indonesia, the prospect of unemployment loomed. On 3 October 1963, Finance Minister Goh Keng Swee announced the establishment of an emergency organisation known as the Department of Economic Defence to “safeguard the livelihood of workers”. “The government has the capacity, determination and adequate financial resources to defend the working people of Singapore against the effects of Indonesian confrontation for any length of time,” said Goh.35

Headed by Labour Commissioner Pang Tee Pow, the department aimed to help “some 8,500 workers in various industries” such as “sago, rubber processing, rattan, coffee, coconut oil and pepper”. Of these, 4,700 were expected to be made redundant. Under the scheme, affected workers would still continue to work for their employers even after production had stopped, and both the government and the employer would each pay affected workers one-third of their normal earnings. As a result, the workers would continue to receive two-thirds of their wages.36

Training and reskilling plans were also in place should the economic situation persist for a protracted period. In December 1963, the Economic Defence Ordinance was passed to enact these support measures which were expected to cost the government $1 million a month.37

Public Education

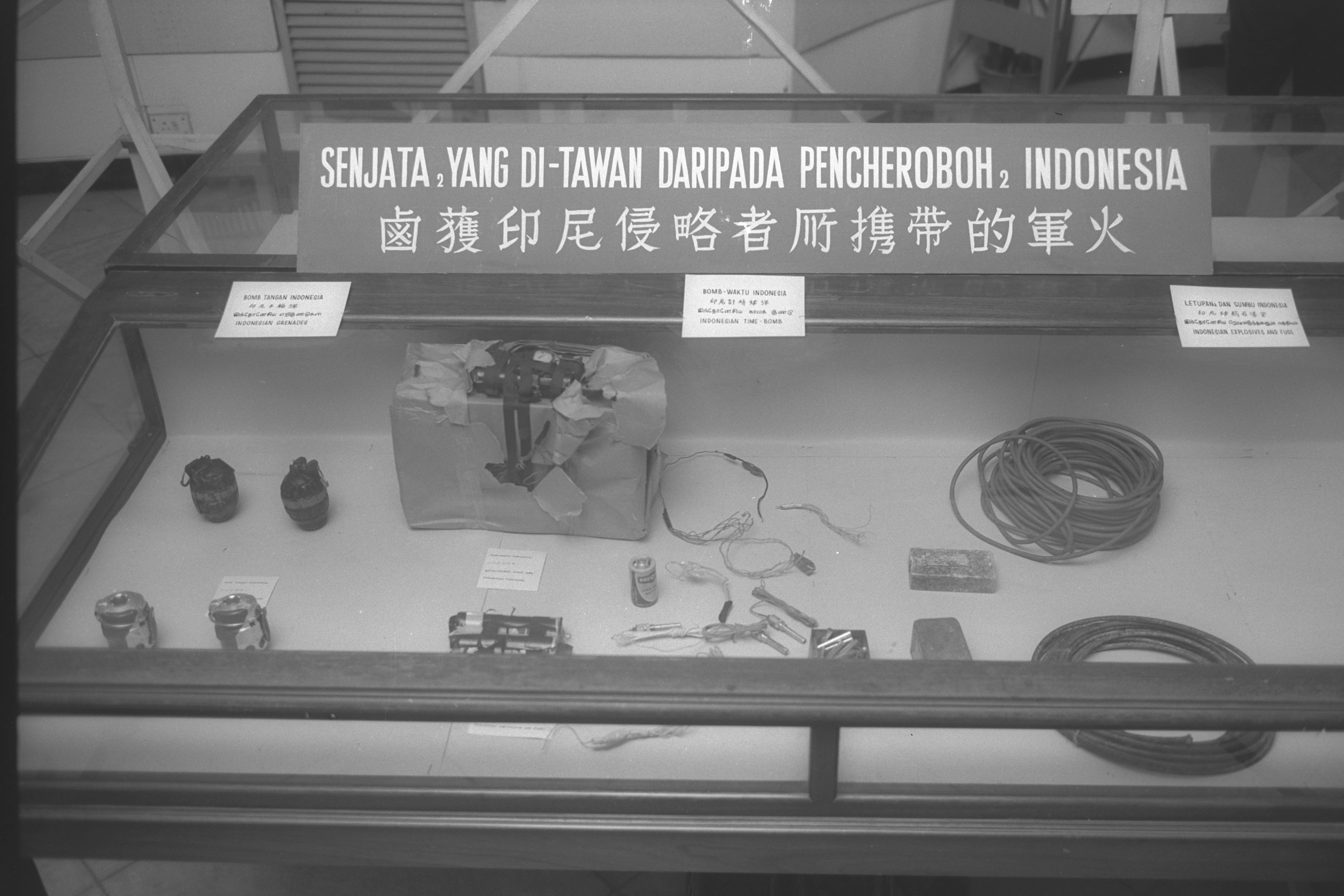

The government also acted to educate the public about Konfrontasi. On 20 July 1964, Woon Wah Siang, permanent secretary at the Ministry of Culture, sent a missive to the commissioner of police, the director of the Special Branch, and heads of the Housing and Development Board and Public Utilities Board, among others. He asked them to organise an exhibition to “bring home to the people through visual means the challenge of confrontation”. It would show “both Indonesian aggressive intentions towards Malaysia” and the countermeasures deployed.38

Titled the “Challenge of Confrontation”, the exhibition was opened by Culture Minister S. Rajaratnam on 2 October 1964, and showcased captured Indonesian automatic weapons, parachutes and kits, all “under the watchful eyes of police guards”. In total, 337,000 people visited the exhibition at the Victoria Memorial Hall, which then travelled to community centres to allow more people to see it.39

The End of Konfrontasi

Sukarno, already discredited by an abortive coup in October 1965, was finally deposed by General Suharto on 11 March 1966.40 Under Suharto, Indonesia changed course in its foreign policy and rejoined the United Nations in April 1966. In the following month, Suharto signalled his desire to end Konfrontasi and Adam Malik, the new foreign minister, met Malaysia’s Deputy Prime Minister Tun Abdul Razak on 29 May in Tokyo.41 In June 1966, Jakarta recognised Singapore’s independence from Malaysia. On 12 August 1966, Konfrontasi formally ended after Indonesia and Malaysia concluded a peace treaty.42

The peace treaty, however, did not completely reset relations between Singapore and Jakarta. That had to wait until 1973. On 28 May that year, Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew visited the Kalibata Heroes Cemetery in South Jakarta as part of his trip to Indonesia. With solemn music playing in the background, Lee “was escorted to sprinkle flowers” on the graves of Indonesian generals who had fallen during the 30 September 1965 coup. Twenty metres away were the graves of two Indonesian marines – Osman Haji Mohamed Ali and Harun Said – who were hanged in Singapore on 17 October 1968 for their part in the MacDonald House bombing. Lee then walked over to their graves and “sprinkled flowers on them”. This action, praised by Indonesian newspapers as a “magnanimous gesture”, touched the Indonesian people deeply and turned the final page on an unhappy episode in the history of both countries.43

Or so it was thought. In February 2014, the Indonesian navy announced that it would name its newly acquired second-hand corvette the KRI Usman Harun, after the two marines responsible for the MacDonald House bombing.44 In response, Singapore barred the warship from calling at Singapore and announced that the Singapore Armed Forces would not carry out military exercises with this ship.45 Indonesia’s armed forces commander General Moeldoko later apologised for the naming decision, and Singapore resumed bilateral ties with the Indonesian armed forces.46

On 10 March 2015, on the 50th anniversary of the MacDonald House bombing, a memorial to the victims of Konfrontasi was unveiled.47 Situated at Dhoby Ghaut Green, a slice of quiet amid busy Orchard Road, the memorial is a reminder of a time when Singapore experienced the fear, terror and anguish of being the urban frontline in a low-intensity war marked by uncertainty, anxiety and randomness.

Alvin Tan is an independent researcher and writer focusing on Singapore history, heritage and society. He is the author of Singapore: A Very Short History – From Temasek to Tomorrow, 2nd edition (Talisman Publishing, 2022) and the editor of Singapore at Random: Magic, Myths and Milestones (Talisman Publishing, 2021).

Notes

-

Abdul Fazil, “Hunt for Bomber,” Straits Times, 11 December 1963, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Abdul Fazil, “Hunt for Bomber.” ↩

-

“Soekarno’s 3-Pronged Offensive – by the Tengku,” Straits Times, 12 December 1963, 12; “Hunt for Mysterious Bomber Continues,” Straits Times, 13 December 1963, 11; “Police Combing Sennett Estate for Bomb Man,” Straits Times, 15 December 1963, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Two on Bombing Charge,” Straits Times, 12 May 1964, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

T.F. Hwang and Yeo Toon Joo, “Court Is Told of Four on a Bombing Mission,” Straits Times, 16 April 1964, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Hwang and Yeo, “Court Is Told of Four on a Bombing Mission”; Felix Abisheganaden, “‘‘Assassinate the Tengku’ Order,” Straits Times, 23 April 1964, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Abdul Fazil, “Hunt for Bomber.” ↩

-

J.A.C. Mackie, Konfrontasi: The Indonesia-Malaysia Dispute, 1963–1966 (New York: Published for the Australian Institute of International Affairs by Oxford University Press, 1974), 125. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 327.5950598 MAC) ↩

-

The Federation of Malaysia was formed on 16 September 1963, following the merger of the Federation of Malaya, Singapore, North Borneo (Sabah) and Sarawak. ↩

-

George McT. Kahin, “Malaysia and Indonesia,” Pacific Affairs 37, no. 3 (Autumn 1964): 260; Donald Hindley, “Indonesia’s Confrontation with Malaysia: A Search for Motives,” Asian Survey 4, no. 6 (June 1964): 907. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Lim Tin Seng, “Merger with Malaysia,” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published 3 November 2017. ↩

-

Mackie, Konfrontasi, 181; M.C. Ricklefs, A History of Modern Indonesia, c. 1300 to the Present, 2nd ed. (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1993), 273. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.8 RIC). Ricklefs asserts that the term “Ganyang Malaysia” has been “usually but less accurately translated as ‘Crush Malaysia’”. ↩

-

“Sishi yu yinni tegong luowang qianru jiandie duo bei kou bu jingfang jixu jibu yudang kexia jin sheng yixie canyu fenzi xiaoyaofawai tumoubugui xingdong” 四十餘印尼特工落網潛入間諜多被扣捕警方繼續緝捕餘黨刻下僅剩一些殘餘份子逍遙法外圖謀不軌行動 [More than forty Indonesian agents were arrested and infiltrated. Most of the spies were arrested. The police continue to arrest the remaining members of the party. Only a few remnants of the party are still at large and plotting misdeeds], 南洋商报 Nanyang Siang Pau, 9 April 1964, 5. (From NewspaperSG); Abisheganaden, “‘Assassinate the Tengku’ Order.” ↩

-

Howard Dick, “Review: Britain and the Confrontation with Indonesia, 1960–1966,” The International History Review 28 no. 1 (March 2006): 217. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Due to land reclamation and urban redevelopment, Katong Park, which had a bathing pagar (swimming enclosure) when it opened in the 1930s, has since lost its seafront and its size reduced. It was built above the buried remains of Fort Tanjong Katong. ↩

-

“Bomber Sought After Blasts in Park,” Straits Times, 27 September 1963, 1; “Where Will Bomber Strike Next?’ Fear,” Straits Times, 28 September 1963, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Bomb Wrecks Car,” Straits Times, 7 October 1963, 1; “Mystery Blast Wrecks a Car,” Straits Times, 7 October 1963, 20; “Mad Bomber May Be Experimenting,” Straits Times, 8 October 1963, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Where Will Bomber Strike Next?”; “$3,000 Reward to Catch the Mad Bomber,” Straits Times, 23 October 1963, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Hotel Bomb Linked With Other Blasts,” Straits Times, 9 March 1964, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Record of the Wreckers,” Straits Times, 16 May 1965, 16; Abu Fazil and Cheong Yip Seng, “Bomb Kills Two,” Straits Budget, 22 April 1964, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Attempt to Blow Up Merdeka Bridge,” Straits Times, 24 May 1964, 2; “Sabotage Bid on Bridge,” Straits Budget, 29 July 1964, 13. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“MacDonald House,” National Heritage Board, last accessed 20 May 2023, https://www.roots.gov.sg/places/places-landing/Places/national-monuments/macdonald-house; National Library Board, “MacDonald House Bombing Occurs,” in HistorySG. National Library Board Singapore. Article published 2014; Mohamed Effendy Abdul Hamid and Kartini Saparudin, “MacDonald House Bomb Explosion,” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published 7 August 2014. ↩

-

Jackie Sam, et al., “Terror Bomb Kills 2 Girls at Bank,” Straits Times, 11 March 1965, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Death for Indon Bombers,” Straits Times, 21 October 1965, 11; “S’pore Govt Gives Reasons for ‘No’ to Pleas for Mercy,” Straits Times, 18 October 1968, 14; “Singapore Embassy in Jakarta Sacked,” Straits Times, 18 October 1968, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Harold James and Denis Sheil-Small, The Undeclared War: The Story of the Indonesian Confrontation 1962–1966 (Kuala Lumpur: University of Malaya Co-operative Bookshop Ltd., 1979), 152–53. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RUR 327.5950598 JAM) ↩

-

Richard Moore, “Where Her Majesty’s Weapons Were,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 57, no. 1 (15 September 2015), https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.2968/057001019. ↩

-

Peter Hennessy and James Jinks, The Silent Deep: The Royal Navy Submarine Service Since 1945, e-book. (London: Penguin, 2015), 553. (From NLB OverDrive) ↩

-

Hennessy and Jinks, The Silent Deep, 553. ↩

-

Abisheganaden, “‘Assassinate the Tengku’ Order.” ↩

-

Jaime Koh, “Vigilante Corps,” in Singapore Infopedia. From National Library Board Singapore. Article published 29 March 2016. The Vigilante Corps was absorbed into the Special Constabulary on 22 September 2022, marking the end of 55 years of service to the nation. See “SPF’s Vigilante Corps: The End of an Era,” Frontline, 12 January 2023, https://www.hometeamns.sg/frontline/spfs-vigilante-corps-the-end-of-an-era/. ↩

-

“Big Hunt for Killers,” Straits Times, 4 March 1965, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Soek Loses 10 Men at Kota Tinggi,” Straits Times, 9 April 1965, 1; Gabriel Lee, “How Our Boys Routed All the Kota Tinggi Gang,” Straits Times, 12 April 1965, 1; “Well Done SIR! Says Tengku,” Straits Times, 6 April 1965, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Premier Lee Pays Tribute to SIR,” Straits Times, 7 May 1965, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Daniel Wei Boon Chua, “CO15054 = Konfrontasi: Why It Still Matters to Singapore,” S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, 16 March 2015, https://www.rsis.edu.sg/rsis-publication/idss/co15054-konfrontasi-why-it-still-matters-to-singapore/. Between 1963 and 1964, imports declined by 23 percent while exports declined 31 percent. “Surviving Our Independence,” SG101, last updated 4 September 2023, https://www.sg101.gov.sg/economy/surviving-our-independence/1959-1965/. ↩

-

Overall, the economic blow dealt by Konfrontasi was not as severe as expected. “Move to Help 8,500 Hit by Trade Boycott,” Straits Times, 4 October 1963, 1. (From NewspaperSG). Goh Keng Swee estimated that Indonesians stood to lose $840 million in trade revenue with Singapore alone. Cheng Siok Hwa noted that GDP fell by 4 percent and “a drop of 18% in value added was recorded in the wholesale and retail trade, restaurants and hotels sector, followed by a 6% in transport, storage and communications”. Recovery, however, came in 1965. See Cheng Siok Hwa, “Economic Change in Singapore, 1945–1977,” Southeast Asian Journal of Social Science 7, nos. 1–2 (1979): 92. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website). ↩

-

“Move to Help 8,500 Hit by Trade Boycott”; “Economic Defence Ordinance 1963,” Bill 7 of 1963, Bills Supplements, Singapore Statutes Online, 6 December 1963, https://sso.agc.gov.sg/Bills-Supp/7-1963/Published/19631206?DocDate=19631206; “Trade Halt Aid to Cost Govt $1m. a Month,” Straits Times, 7 December 1963, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Public Service Division, “Challenge of Confrontation Exhibition,” Government Records, 20 July 1964. (National Archives of Singapore, file no. MC 130/64) ↩

-

“Captured Indon Arms on Show,” Straits Times, 2 October 1964, 4; “Confrontation Show a Big Hit,” Straits Times, 3 October 1964, 11; “337,000 Saw This Show,” Straits Times, 13 October 1964, 4; “Show Moves On,” Straits Times, 25 October 1967, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Konfrontasi (Confrontation) Ends,” in HistorySG. From National Library Board Singapore. Article published 2014; Ricklefs, History of Modern Indonesia, 289. ↩

-

Ricklefs, History of Modern Indonesia, 290. ↩

-

Jackie Sam, “Indonesia Recognises Singapore,” Straits Times, 5 June 1966, 1; “Confrontation Ends,” Straits Times, 12 August 1966, 1; “25 Years Ago,” Straits Times, 11 August 1991, 22. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lee Khoon Choy, Diplomacy of a Tiny State, 2nd ed. (Singapore: World Scientific, 1993), 270–71. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 327.5957 LEE) ↩

-

“Singapore Urges Jakarta Not to ‘Reopen Old Wounds’,” Straits Times, 7 February 2014, 1; “Singapore: Naming Indonesian Warship After Marines Would Open Old Wounds,” Today, 7 February 2014, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Jermyn Chow, “Indonesian Warship Usman Harun Disallowed from Calling at Singapore Ports and Naval Bases,” Straits Times, 18 February 2014, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/indonesian-warship-usman-harun-disallowed-from-calling-at-singapore-ports-and-naval-bases. ↩

-

“Singapore Welcomes Indonesia’s Apology Over Naming of Frigate,” Straits Times, 16 April 2014, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/singapore-welcomes-indonesias-apology-over-naming-of-frigate-0. ↩

-

Lim Yan Liang, “Memorial to Victims of Konfrontasi Unveiled Near MacDonald House,” Straits Times, 10 March 2015, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/memorial-to-victims-of-konfrontasi-unveiled-near-macdonald-house. ↩