Multi ethnic Enclaves Around Middle Road: An Examination of Early Urban Settlement in Singapore

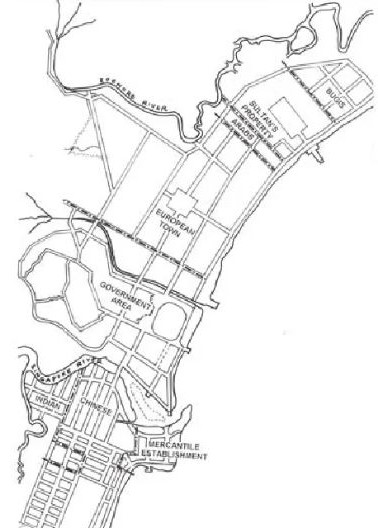

Philip Jackson’s Plan of the Town of Singapore (1822) dictated the layout and structure of the town, and also designated special areas for the various ethnic groups that had settled in Singapore.

Many former British colonies like the Straits Settlements and peninsular Malaya had attracted diverse peoples from neighbouring areas upon their colonisation and establishment with the prospect of employment and economic opportunities. The colony of Singapore, in particular, was a major destination for southern Chinese migrants. If textual accounts are anything to go by, the human landscape after its founding in 1819 was cosmopolitan in character, although the exponential immigration of Chinese groups and their eventual possession of various spheres of influence would alter the course of the island’s subsequent histories. Roland Braddell’s 1934 work Lights of Singapore, for example, described the early composition of the “white people” in colonial Singapore as consisting “English, Irish, Scottish, Welsh, Australians, New Zealanders, Canadians, Americans, Belgians, Danes, Dutch, French, Germans, Greeks, Italians, Norwegians, Portuguese, Russians, Spaniards, Swedes, Swiss and others” (Braddell, 1934:43–5). Braddell painted a similarly diverse composition of non-white communities on the island, but instead of country origin categorised them into particular ethnic groups and sub-groups as follows:

“Malays”: “real” Malays,

Javanese, Boyanese, Achinese,

Bataks, Banjarese, Bugis, Dyaks,

Menangkabau, people

from Korinchi, Jambi, Palembang;

“Klings”: Tamils, Telugus, Malabaris;

“Bengalis” include Punjabis, Sikhs,

Bengalis, Hindustanis, Pathans,

Gujeratis, Rajputs, Mahrattas,

Parsees, Burmese and Gurkhas;

“Asiatics”: Arabs, Singhalese,

Japanese, Annamites, Armenians,

Filipinos, Oriental Jews, Persians,

Siamese and others;

“Chinese”: Hok-kiens, Teo-chius,

Khehs, Hok-Chias, Cantonese,

Hailams, Hok-Chius, and

Kwong-Sais.

The convergence of denominations and dialect identities within larger ethnic groups was an attempt by British administrator to cognise the multifarious communities, as well as a way to map, survey and control the groups. In the process, distinctions that existed between the different ethnic sub-groups were blurred or neutralised, as the use of such categories for control and spatial division disregarded both the hegemonies that existed between the different dialect settler groups, as well as the dynamic nature of multi-ethnic enclave formation and definition. This essay is an attempt to examine two such sub-groups that settled in Singapore in the 19th century, and to explore the shape of their enclaves and built-forms.

The Early Ethnic Landscape

The formation of early ethnic landscapes in Singapore may be attributed to the will of its colonial founder, Thomas Stamford Raffles, whose career straddled Penang, Bencoolen, Java and Singapore. While recuperating from illness in Malacca in 1808, Raffles, then an assistant secretary in Penang, drafted a report to his Government in India advising it not to abandon Malacca nor divert its trade to Penang, as other European or local powers would only capture it to the detriment of the British enterprise. The Governor-General was so impressed that Raffles was appointed Lieutenant-Governor of Java at the age of 30. In 1818, Raffles was instructed to establish British interests in Acheh and in the Riau islands to further control trade in the Straits and to check Dutch encroachment. Arriving in Penang on December 31, he discovered that the Dutch had already occupied Riau, and was determined to stop their advance into Johore. Instead of travelling to Sumatra, he sidestepped protocol and sailed on his own accord to the island of Singapore, arriving there on January 28, 1819. Armed with the knowledge that the island was a thriving city until its destruction four and a half centuries ago, and assisted by his trusted former Malaccan colleague, Colonel William Farquhar, and ship carpenter, Chow Ah Chi, he signed a preliminary agreement with the Temenggong of Johore on January 30 to establish “a factory” on the island (Mills, 1867:60–69).

Raffles was aware of the shortcomings of Penang, Java and Bencoolen, and was determined that his next project would be financially and administratively viable to the directors of the East India Company. He thus advocated governing the island with a small, efficient establishment that worked with clear, effective decisions.1 Returning from Bencoolen in October 1822 after an absence of 39 months, he was thus annoyed that the first appointed British resident, William Farquhar, had not heeded his instructions regarding the layout of the settlement and allowed private individuals to occupy land on the northern bank of the Singapore River – areas he had designated for government use (Lee, 1983). Raffles had personally encountered the example of Penang, where undefined and unregulated landscapes worked against the administration. Within a week, he appointed a Town Planning Committee “in order to afford comfort and security to the different descriptions of inhabitants who have resorted to the Settlement and to prevent confusion and disputes hereafter”.2

Philip Jackson’s Town Plan of 1822 dictated the layout and structure of the city, but it also attempted to deal with the ethnic groups that had settled in Singapore.3 Raffles appointed the committee to mark out “the quarters or departments of the several classes of the native population,”4 and Jackson’s plan showed, on the southern banks of the Singapore river, an area designated for the Chinese, with “Chuliahs” and “Klings” allocated the area further inland on the same side of the river.5 On the northern banks, a “European Town” was marked out occupying the space between the “Government Area” adjacent to the river, and the Sultan’s properties to the northeast, which was flanked by an Arab and Bugis community on each side.

It was probable that funds for constructing public buildings were scarce. Hence, Raffles was prudent with his expenditure and commissioned, besides his residency on top of Forbidden Hill (Fort Canning Hill), only a school (The Institution, 1823) and a church (Saint Andrew’s Cathedral, 1835) on one side of an open field (the Padang today) and esplanade.6 John Crawfurd, the new resident that Raffles had appointed in 1823, could still not develop government buildings around the Padang but could, with the plan, lease land to merchants to build houses. The administration rented John Maxwell’s house for use as a Court House, Government Offices and Recorder’s Office for 500 rupees a month.7 Other houses belonging to Robert Scott, James Scott Clark, Edward Boustead and William Montgomerie around the Padang served as residences and hotels until the land tracts were acquired to build the Town Hall (1862), the Municipal Offices (1926–1929) and the Supreme Court (1939) to establish the government cantonment.8

The “Smaller” Town

Jackson’s 1822 plan for the European Town comprised four parallel roads laid out in the northeast-southwestern direction, and a major intersecting road. This perpendicular road is the present-day Middle Road, named because it either marked mid-distance between the Sultan’s residential compounds and the Government Area, or between the Rochore and Singapore rivers.

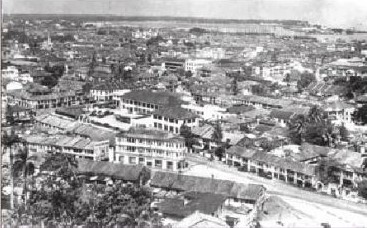

Despite the area’s allocation as European Town, it is likely that Europeans subsequently vacated it because of several reasons. Firstly, the number of Chinese immigrants, perceived as “an industrious race” (Logan, in Hodder, 1953:27) useful for the enterprise, increased from 3,317 persons in 1824 to 86,800 in 1881, many of whom were settling near or within the European Town (Chan, 1976:48). Chinese dialect groups that were not Hokkien, Teochew or Cantonese – the three earliest groups in the southwestern side of Singapore River – were settling on its other side.9 Secondly, with the interiors of the island rapidly cleared by gambier farming, European settlers were able to build their bungalow houses there, and to dwell away from the urbanising city quarters increasingly accommodating mercantile and non-white populations.10

In deference to the earlier Chinese Town on the other side of the river, this later settlement was known colloquially by the Chinese groups as Xiao Bo (Smaller Town) relative to its counterpart Da Bo (Larger Town).11 North Bridge Road and South Bridge Road were two parts of the same street (known as First Street or Big Street) connecting the two “towns” across the river. The parallel roads north of North Bridge Road in Xiao Bo were accordingly numbered, with Waterloo Street called Fourth Street and Short Street near Mount Sophia designated as Seventh Street.

Like the settlement patterns established in Da Bo, prestige, advantage and opportunities were associated with proximity to the British cantonment in Xiao Bo. The distances of these enclaves from the cantonment also indicated the history of their settlement and enclave formation. The Hainanese were the earliest settler group there, followed by the Hakka, Hokchia, Foochow and Henghua groups (Hodder, 1953:35 and Tan, 1986:29). Together with the “Malay,” “Indian” and “Arab” groups, a sprinkling of Hokkien, Teochew and Cantonese groups, as well as the European groups who continued to reside in these areas, a multi-ethnic and multi-religious landscape was established this side of the Singapore River.

The Hainanese Community and Enclave

Of the Chinese dialect groups that occupied areas northeast of the cantonment, the Hainanese community was the largest. Its enclave was adjacent to European churches, army camps and Raffles Hotel, and extended from the seashore along Beach Road westwards towards North Bridge Road.12 The three streets that run perpendicular to these two – Middle Road, Purvis Street and Seah Street – were respectively called Hainan First Street, Hainan Second Street and Hainan Third Street by the Hainanese and other Chinese communities, and a street recognition system different from their “official” designations was thus employed.

Small Hainanese trading vessels were known to have reached Singapore as early as 1821.13 The first settler was recorded as Lim Chong Jin, who arrived in Singapore in 1841 (Chan, 1976:48). By 1881, the Hainanese had constituted about 10 percent of the Chinese population, numbering 8,319 (Tan, 1986:29). As they were late on the scene and their enclave located further from the main godowns at the Singapore River, most Hainanese settlers worked as plantation workers or sailors. Others worked in servicerelated industries and operated provision shops, ship-chandling and remittance services, hotels and coffee shops.14 It was in the food “business” that would bring them most regional fame.15 Ngiam Tong Boon, a Hainanese bartender working at Raffles Hotel first concocted a gin tonic called “The Singapore Sling” in 1915. Nearby, Wong Yi Guan adapted a rice dish served with chicken, which was made famous by his apprentice Mok Fu Swee through his restaurant “Swee Kee Chicken Rice”. Later, this dish would be “re-exported” elsewhere in the region and East Asia as “Hainanese chicken rice”.16 It is also generally acknowledged that the Hainanese brewed the best coffee in Southeast Asia.

The main Hainanese association (Kiung Chow Hwee Kuan) and clan temple building was built in 1857 in three adjoining shophouses along Malabar Street.17 In 1878, it moved to its present location along Beach Road, and later underwent renovations in 1963. The Hainanese in Singapore were a close-knit and clannish society, as evidenced by the compulsory social initiation of new migrants, as well as the welfare and clan practices provided by the community within the enclave (Chan, 1976:50). Besides the main association and temple complex at Beach Road,21 additional sub-clan associations can be found along the three main streets, differentiated not only by origin district on Hainan island, but also in combination with clan surnames.18

The location of the enclave, edged by a major street (Middle Road) and the water’s edge with a docking pier and communal facilities, ensured the general prosperity of the enclave until the 1980s, when urban renewal decanted a large portion of its original residential community. By this time, the population had grown and dispersed, mainly to villages and estates all over the island.

The Japanese Community and Enclave

In post-World War II ethnic census calculations in Singapore, the Japanese community occupies an “other” or foreign component. This is due to Japan’s military occupation of Southeast Asian states during World War II and the repatriation of Singapore’s non-military Japanese residents subsequent to the Occupation. In the period leading up to the creation of a new independent state in 1965, the former existence of a Japanese enclave in the Smaller Town, and its connections to commercial and everyday life in pre-war Singapore were displaced to ameliorate the memory of the “replacement” Asian colonisers. However, some distinction may be made between these two Japanese groups of prewar settlers and World War II military occupants, even if some may have assumed both identities. One such discernment of the two groups at the outbreak of war comes from Lee Kuan Yew, the first prime minister of Singapore: “Later that same day, a Japanese non-commissioned officer and several soldiers came into the house. They looked it over and, finding only Teong Koo and me, decided it would be a suitable billet for a platoon. It was the beginning of a nightmare. I had been treated by Japanese dentists and their nurses at Bras Basah Road who were immaculately clean and tidy. So, too, were the Japanese salesmen and saleswomen at the ten-cent stores in Middle Road. I was unprepared for the nauseating stench of their unwashed clothes and their bodies of these Japanese soldiers” (Lee, 1998:54–55).

Although records of Japanese junks trading in Malacca and various other regional Southeast Asian ports existed as early as the 17th and 18th centuries, the local Japanese community heralds its first settler as Otokichi Yamamoto, who migrated to Singapore in 1862 and who died here in 1867 (Mikami, 1998:14–21). Uta Matsuda, the first female Japanese settler, ran a grocery shop with her Chinese husband in the 1860s. With the establishment of a trade consulate in 1879, an embassy in 1889, the introduction of the Japanese-made jinrickshaw in 1884 and setting up of Japanese shops and companies, the community increased substantially by the close of the 19th century. At the end of the Taisho period or the beginning of the 20th century, it was estimated that 6,950 Japanese were residing in Singapore and Malaya (Mikami, 1998:26–7).

The development of the Japanese enclave in Singapore is connected to the establishment of brothels east of the Singapore River. No Japanese brothels were in operation in 1868, but by the turn of the century, the group of brothels located along Hylam, Malabar, Malay and Bugis Streets had displaced the earlier brothel district in the Kampong Glam area operated by Malays and later by Chinese and Europeans (Warren, 1993:44–46). Unlike the Chinese brothels in Kreta Ayer area, which served only Chinese clients and differentiated into class types, Japanese brothels rarely discriminated against patrons on the basis of ethnicity, but were similarly divided into “higher and lower grade” houses (Warren, 1993: 50–51). The “success” of the brothels in the Southeast Asian region was followed by the migration of merchants, shopkeepers, doctors and bankers to bolster the economy of a country yet unable to compete globally as a modern industrial nation. Indeed, with the abolition of prostitution in Singapore in 1920, these trades replaced the brothel “business” and sustained the community that by then had its own newspaper (Nanyo Shimpo, 1908), a cemetery (1911), a school (1912) and a clubhouse (1917) (Mikami, 1998:22–23). By 1926, the Japanese community in Singapore had grown to occupy the area bound roughly by Prinsep Street, Rochore Road, North Bridge Road and Middle Road, alongside the Hainanese and other enclaves.

Middle Road, which connected the Mount Sophia area to the sea, was known to the community as Chuo Dori or Central Street. The Japanese prostitutes dubbed Malay Street Suteretsu, a transliteration of the English word “street”, and this was contrasted with another “Japanese” area known as Gudangu (from “godown”), located near the mouth of the Singapore River and Collyer Quay, where Japanese shipping lines had established offices and agencies (Mikami, 1998:28–29). Like the Hainanese, the Japanese created their own system of street names, layered over or corrupting official British ones.

Built Forms in the Enclaves

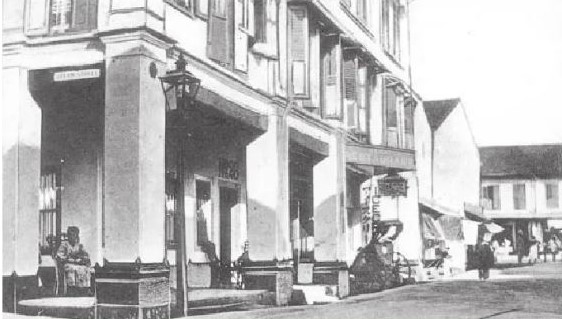

On both sides of the Singapore River, shophouses were the main form of residential and commercial buildings to accommodate the migrants and settlers as well as their trades. While their origin and accompanying architectural styles are of some conjecture, the use and design of the shophouse were also regulated by the dictates of the 1822 Town Plan.19 Raffles’ instructions to the Town Planning Committee indicated that “all houses constructed of brick or tile should have a uniform type of front, each having a verandah of a certain depth, open at all times as a continuous and covered passage on each side of the street” (Lee, 1984:7; Hancock, 1986:21). Besides sheltering pedestrians from inclement weather with the verandah (known as the five-foot way), the mandated co-ordination of these built forms also enabled the provision of collective sanitary services like drainage and waste disposal, and of course, permitted ease of administrative control. The ordained use of brick proved to be practical, as it reduced the risk of fire to the residential and commercial districts. Elsewhere in the Straits Settlements, severe fires destroyed areas in Georgetown in 1808, 1812, 1813, 1818 due to the use of non-permanent and combustible materials, and a major fire almost burnt down the entire town of Kuala Lumpur in 1881 (Tjoa-Bonatz, 1998:126). The use of the covered five-foot way for shophouses was only implemented gradually in Penang in 184920 and later in the states of Selangor (1890), and Perak (1893) (Lim, 1993:50–51).

These two- or three-storeyed buildings generally provided space for commercial activity at the pedestrian level and residential space above it, and were separated by structural, brick party walls. The width of each shophouse was limited by available spans of the timber floor and roof beams at about six metres, and the linear interior spaces were punctuated with air wells for light and ventilation. The brick and plaster façades accommodated simple timber-louvred windows as well as doors set within pilasters and other ornaments like architraves and mouldings. Local architectural historian Lee Kip Lin suggested that the ornamentation found on early shophouses were Chinese as evidenced by those in Malacca, but by the turn of the century these had transferred from “pure Chinese” to a lavish application of European classical details.21 The efficacy of the building type was to ensure its continued construction up till the 1940s in Singapore and Malaysia, while undergoing different “style” and functional adaptations.

While physically similar, the use of shophouses within the Hainanese and Japanese enclaves differed from those on the other side of the Singapore River. As a minor enclave, the Hainanese had to accommodate residential, communal as well as commercial functions within a smaller district area, with fewer shophouses. Unlike those clan associations at Club Street occupying entire shophouses, the large number of Hainanese clan associations was housed predominantly in the upper storeys, with the space at the ground-level reserved for remittance services, restaurants, and coffee shops etc. One could sometimes find multiple clan associations and businesses occupying the same ophouse, as two or more businesses may share the same ground-level shop space, and two or more clans may share spaces above ground level. Wong Chin Soon, an enclave resident, recounted that of the 20 or so remittance companies that were found along Purvis Street, many doubled up as drapers, printers, shiphandling services, umbrella makers, confectioneries, and hotels (Wong, 1989:309). With the decanting of its residents in the 1980s, most of the clan associations have remained in the vicinity although the uses for ground level shops have changed.

Either as brothels or businesses, the pre-war Japanese also converted interior spaces of shophouses for functions relevant to their use, with attention to Japanese cultural and business practices. A 1910 description of the Suteretsu by an anonymous reporter is as follows: “Around nine o’clock I went to see the infamous Malay Street. The buildings were constructed in a western style with their facades painted blue. Under the verandah hung red gas lanterns with numbers such as one, two, or three, and wicker chairs were arranged beneath the lanterns. Hundreds and hundreds of young Japanese girls were sitting on the chairs calling out to passers-by, chatting and laughing… most of them were wearing yukata of striking colours”.22

The spaces on the upper floors of the brothels were segmented into rooms or cubicles, but denoted by tatami sizes. Unlike those in the Kreta Ayer area, the Japanese brothels averaged six tatami mats in size, housed less women, and were thus more spacious.23 The general functions of the shophouse were inverted: the upper floors were used for “business” while the ground level spaces were used as dwellings, waiting areas or offices. Rudimentary services included a common bathroom on each floor and a kitchen at the back of the house. When prostitution was abolished in 1920, these shophouses returned to commercial or other uses at ground level.

An example of a business space, for which records still exist, was the Echigoya draper that had its premises at Middle Road (Mikami, 1998:36–41 & 82–95). In its 1908 shop, textiles and clothing were stored in full-height timber cabinets that ran along the lengths of the ground level walls, accentuating the linear space (see picture). On one length side a raised platform is also constructed, known as the koagari, where customers would sit while they examine the merchandise. For the sake of non-Japanese patrons, a circular marble table and chairs were also provided. When it moved down the road in 1928 to occupy two adjoining shophouses; the open, uncluttered aesthetic was maintained although waist-high timber-framed and glass-panelled display cabinets were used to enable customer circulation around the wares.

Multi-ethnic Societies – Past and Present

The Japanese community was repatriated after the end of World War II, and for the subsequent four years, no Japanese person was allowed entry into Singapore (Gubler, 1972:130). The enclave became dilapidated by the end of the 1980s and many of its shophouses have since been demolished. In the early 1990s, a Japanese developer leased the plot of land where the brothel district used to be and reconstructed most of the shophouses, adding glass roofs over the internal streets to create the first air-conditioned, “open-to-sky shopping arcade” in Singapore. Its new designation as Bugis Junction returned the spaces to commercial use and “reincarnated” the earlier shophouses, but by its very act of naming, the area’s earlier multi-ethnic histories were subjugated.

In Contesting Space in Colonial Singapore, local geographer Brenda Yeoh argued that the existence of different systems of street names attested to competing representations of the urban landscape by its different communities rather than the acceptance of a municipallyimposed one (Yeoh, 2003:219–235). The use of their own designations for places and streets by the Hainanese and Japanese, as discussed above, confirms this argument. We may further observe that the original municipal naming of streets within that area as “Malay”, “Malabar”, “Bugis”, and “Hylam,” had only captured the settlement image at one particular moment of Singapore’s colonial history. The subsequent occupation by other sub-groups along those streets and the changing sub-group enclave boundaries or edges (if they existed) showed the failure of colonial mapping and naming along ethnic constituencies.

Hylam Street (Hylam: a transliteration of “Hainan”) was named for the early Hainanese settlers that lived around Malabar Street. No street was named for the Japanese community that settled later along the same streets. By the time the Japanese enclave was taking shape there, the Hainanese community had moved from Hylam Street to the Beach Road area to capitalise on sea frontage and pier facilities. Ironically, Hylam Street itself was later called Japan Street by the Hainanese community after they had moved out as a subsequent rendering of that space. The municipality, however, did not rename the streets to register the changing ethnic complexion of the area.

The spatial and built forms of the two communities, as discussed, also showed the difficulty of generalising or characterising the nature of such enclaves as well as their built forms – especially shophouses which have been described in extant academic and official literature as “ubiquitous”. The builders and occupants of shophouses around Middle Road adapted them to suit the extant social and economic conditions they faced, and demonstrated the flexibility of such forms by converting their use when conditions changed or were altered. The shophouse spaces around Middle Road served the needs of not only their own respective communities, but also with regard to and in consideration of other ethnic sub-group members residing around it. Such uses by different ethnic groups represent important aspects of multi-ethnic community formation and living in Singapore, or at least that, which is found in the Smaller Town.

By describing the history of enclaves and built-forms of these two sub-groups, I have privileged their discussion over the other groups that co-existed in Xiao Bo, the Smaller Town, and those in other areas of colonial Singapore. My attempts to discuss what I called “multi-ethnic enclaves” are limited to the available texts and expressions of these two groups. This is not intentional, and it is hoped that by beginning with two of them, a sketch of the urban history of the area between the Singapore and Rochore rivers may materialise eventually with the help of other scholars and researchers. It is also hoped that this essay serves in a small way towards the writing of Singapore’s larger multiethnic history that may be clarified when the nature of its constituent forms are further discussed and made available.

Assistant Professor

Department of Architecture,

School of Design and Environment

National University of Singapore

REFERENCES

B. W. Hodder, “Racial Groupings in Singapore,” Malayan Journal of Tropical Geography 1 (1953): 25–36. (Call no. RDTYS 910.0913 JTG)

Brenda S.A. Yeoh, Contesting Space in Colonial Singapore: Power Relations and the Built Environment (Singapore: Singapore University Press, 2003). (Call no. RSING 307.76095957 YEO)

Chan Sek Keong, The Hainanese Commercial & Industrial Directory, Republic of Singapore, vol. 2. (Singapore: Hainanese Association of Singapore, 1976)

F. G. Stevens, “A Contribution to the Early History of the Prince of Wales Island,” Journal of the Malayan Branch, Royal Asiatic Society 7, no. 3 (108) (October 1929): 377–414. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Greg Gubler, The Pre-Pacific War Japanese Community in Singapore ([Provo, Utah]: G. Gabler, 1972). (Call no. RSING 301.45195605957 GUB)

History of the Chinese Clan Associations in Singapore (Singapore: Singapore Federation of Chinese Clan Associations, 1986). (Call no. RSING q959.57 HIS-[HIS])

J. Kathirithamby-Wells, “Early Singapore and the Inception of a British Administrative Tradition in the Straits Settlements (1819–1832),” Journal of the Malayan Branch, Royal Asiatic Society 42, no. 2 (December 1969): 48–73. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

James Francis Warren, Ah Ku and Karayuki-San: Prostitution in Singapore, 1870–1940 (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1993). (Call no. RSING 306.74095957 WAR)

Jon S. H. Lim, “The Shophouse Rafflesia: An Outline of Its Malaysian Pedigree and Its Subsequent Diffusion in Asia,” Journal of the Malayan Branch, Royal Asiatic Society 66, no. 1 (294) (1993): 47–66. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Kiung Chow Hwee Kuan, Singapore 新加坡琼州会馆, Xinjiapo Qiongzhou hui guan yi san wu zhou nian ji nian te kan 新加坡琼州会馆一三五周年纪念特刊 [Singapore Qiongzhou Huay Kuan 135th Anniversary Special Issue] (Xinjiapo 新加坡: Xinjiapo Qiongzhou hui guan 新加坡琼州会馆, 1989). (Call no. Chinese RSING q369.25957 SIN)

L. A. Mills, Constance M. Turnbull and D. K. Bassett, “British Malaya 1824–67,” Journal of the Malayan Branch, Royal Asiatic Society 33, no. 3 (191) (1960): 36–85. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Lee Kip Lin, Emerald Hill: The Story of a Street in Words and Pictures (Singapore: National Museum, 1984). (Call no. RSING q959.57 LEE-[HIS])

Lee Kip Lin, The Singapore House 1819–1942 (Singapore: Times Editions, 1988). (Call no. RSING 728.095957 LEE)

Lee Kuan Yew, The Singapore Story: Memoirs of Lee Kuan Yew (Singapore: Times Editions, 1998). (Call no. RSING 959.57 LEE-[HIS])

Mai Lin Tjoa-Bonatz, “Ordering of Housing and the Urbanisation Process: Shophouses in Colonial Penang,” Journal of the Malayan Branch, Royal Asiatic Society 71, no. (2) (275) (1998): 123–36. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Prewar Japanese Community in Singapore: Picture and Record (Singapore: The Japanese Association, Singapore, 1998). (Call no. RSING 305.895605957 PRE)

Roland Braddell, The Lights of Singapore (London: Metheun & Co. Ltd., 1934). (Call no. RRARE 959.57 BRA; microfilm NL25437)

T.H.H. Hancock, Coleman’s Singapore, Monographs of the Malaysian Branch, Royal Asiatic Society Series no. 15. (Kuala Lumpur: MBRAS, 1986). (Call no. RSING q720.924 COL.H)

Wong C. S., Roots the Series #3 (Singapore: Seng Yew Book Store and Shin Min News Daily, 1992)

NOTES

-

J. Kathirithamby-Wells, “Early Singapore and the Inception of a British Administrative Tradition in the Straits Settlements (1819–1832),” Journal of the Malayan Branch, Royal Asiatic Society 42, no. 2 (December 1969): 50–51. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website). Also F. G. Stevens, “A Contribution to the Early History of the Prince of Wales Island,” Journal of the Malayan Branch, Royal Asiatic Society 7, no. 3 (108) (October 1929): 385. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website). Raffles had suggested to his superiors that this manner of administration should be implemented for all British colonies in Southeast Asia. ↩

-

Town Planning Committee, as quoted in T.H.H. Hancock, Coleman’s Singapore, Monographs of the Malaysian Branch, Royal Asiatic Society Series no. 15. (Kuala Lumpur: MBRAS, 1986), 16. (Call no. RSING q720.924 COL.H) ↩

-

Lee Kip Lin noted that Raffles formulated his plan to divide the town into “neighbourhoods” or “campongs” as early as his second visit to Singapore in June 1819. From Lee Kip Lin, The Singapore House 1819–1942 (Singapore: Times Editions, 1988), 17. (Call no. RSING 728.095957 LEE) ↩

-

J.R. Logan, “Notices of Singapore”, Journal of the Indian Archipelago, 1854, as quoted in B. W. Hodder, “Racial Groupings in Singapore,” Malayan Journal of Tropical Geography 1 (1953): 27. (Call no. RDTYS 910.0913 JTG) ↩

-

The Chinese were moved inland in 1822 to establish a “principal mercantile establishment” on the tongue of land adjacent to the river. From Lee, Singapore House 1819–1942, 19. ↩

-

Farquhar’s residency was at the foot of the hill near the river, at a corner of High Street. Lee, Singapore House 1819–1942, 149. ↩

-

This building, subsequently bought by the government, was extended as a courthouse in 1874 by J.F.A. McNair and then as a parliament house in 1954 by T.H.H. Hancock of the Public Works Department. From Hancock, Coleman’s Singapore, 22–29. ↩

-

The land where Scott’s house stood was acquired to build Raffles Hotel by the Sarkies brothers. Lee, Singapore House 1819–1942, 148–9. ↩

-

There are also pockets of settlements of Cantonese-Hakka groups although the Kreta Ayer area is generally acknowledged as a “Cantonese” area. ↩

-

Gambier farming employed shifting cultivation, and was destructive as forests were cleared for fuel to boil the gambier leaves. Lee Kip Lin noted that there were about 5,000 acres of gambier and pepper plantations owned mainly by the Chinese by 1841. He also noted that Europeans were moving to the “countrysides” as early as 1822, with James Pearl occupying Pearl’s Hill in 1822 and Charles Ryan in Duxton Hill in 1827. From Lee Kip Lin, Emerald Hill: The Story of a Street in Words and Pictures (Singapore: National Museum, 1984), 1. (Call no. RSING q959.57 LEE-[HIS]) ↩

-

In contemporary descriptions of Singapore by academics and laypersons, Chinatown is acknowledged only by the area on the southwestern areas of the river. The indication of a “second” Chinatown can be seen on a map reproduced by Hodder, “Racial Groupings in Singapore,” fig. 5 on p. 31. ↩

-

A 1953 map shows that the enclave may have “expanded” in the northwest direction up to Bencoolen Street. Hodder, “Racial Groupings in Singapore,” 35. ↩

-

The trade was in wax, tiles, shoes, umbrellas, paper, dried goods and Chinese medicinal herbs. Chan Sek Keong, The Hainanese Commercial & Industrial Directory, Republic of Singapore, vol. 2. (Singapore: Hainanese Association of Singapore, 1976), 48. ↩

-

They were “noted as waiters, cooks and domestic servants …,”in Hodder, 1953:34. This was also discussed in Chan, Hainanese Commercial & Industrial Directory, 48. ↩

-

From a 1976 address/telephone list provided in Chan, Hainanese Commercial & Industrial Directory, 209–96. I counted 19 coffee shops/restaurants and 6 hotels within the enclave. ↩

-

The restaurant was so famous that one can still find chicken rice stalls throughout Singapore and Malaysia bearing the similar name “Swee Kee chicken rice”. The original restaurant was located at Nos. 51-53, Middle Road, recently demolished. Wong C. S., Roots the Series #3 (Singapore: Seng Yew Book Store and Shin Min News Daily, 1992), 51–60. ↩

-

This was No. 6, Malabar Street. Like other coastal Chinese, the main deity for this temple was Ma Chor (or Tian Hou), goddess of safe passage at sea. Chan, Hainanese Commercial & Industrial Directory, 9. ↩

-

Compiled from a 1976 address/telephone list provided in Chan, Hainanese Commercial & Industrial Directory, 209–96. These smaller clan associations, located mainly in Seah Street were started after 1920 when the ban on immigrant Hainanese women was lifted in China. ↩

-

Both Jon S. H. Lim and Mai Lin Tjoa-Bonatz have discussed the possible origins of the shophouse in Southeast Asia, as a form that may have predated European arrival and have had accumulative influences since the 15th century. Jon S. H. Lim, “The Shophouse Rafflesia: An Outline of Its Malaysian Pedigree and Its Subsequent Diffusion in Asia,” Journal of the Malayan Branch, Royal Asiatic Society 66, no. 1 (294) (1993): 47–66; Mai Lin Tjoa-Bonatz, “Ordering of Housing and the Urbanisation Process: Shophouses in Colonial Penang,” Journal of the Malayan Branch, Royal Asiatic Society 71, no. (2) (275) (1998): 123–36. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Conversation with Jon S. H. Lim, 11 November 2003. ↩

-

It was also likely that European or local architects were beginning to engage in the design of shophouses, abetted by the availability of pattern books. Lee, Emerald Hill, 7–8. ↩

-

As cited in James Francis Warren, Ah Ku and Karayuki-San: Prostitution in Singapore, 1870–1940 (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1993), 41. (Call no. RSING 306.74095957 WAR) ↩

-

Warren, Ah Ku and Karayuki-San, 52. He noted that there were 5–7 prostitutes in a Japanese brothel compared to 15–18 in Chinese brothels in Chinatown, Warren, Ah Ku and Karayuki-San, 47. ↩