Joseph Conrad’s Singapore

Joseph Conrad’s visits to Singapore in the late 19th century are immortalised in some of his novels, such as Lord Jim, The End of the Tether and The Shadow-Line.

By Ian Burnet

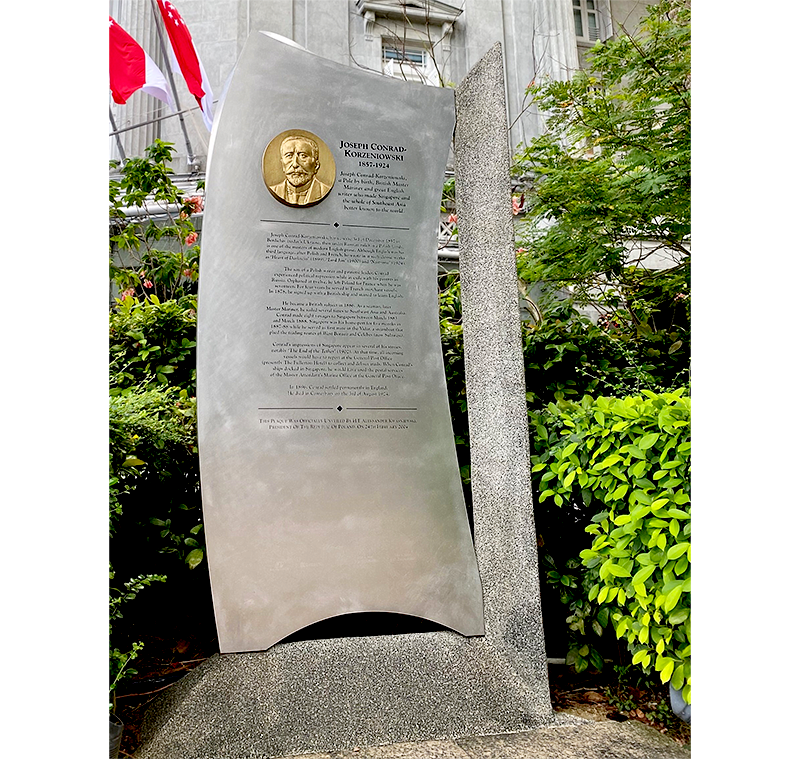

A metal plaque dedicated to Joseph Conrad stands in front of the Fullerton Hotel in Singapore. The text on the memorial describes Conrad as a “British Master Mariner and great English writer who made Singapore and the whole of Southeast Asia better known to the world”.

The plaque, which is well over 2 m high, can be found just across a small road from the hotel, close to Cavenagh Bridge. Flanked by shrubbery, the memorial’s placement is no coincidence. Conrad had been a seaman before turning to writing and Singapore had served as his homeport for five months in the late 1880s. Conrad would have been a regular visitor to the spot where the Fullerton Hotel is now because this was where the Master Attendant’s Office had been. (The Master Attendant, whom Conrad referred to as the Harbour Master, was responsible for the control of shipping in the roadstead.)

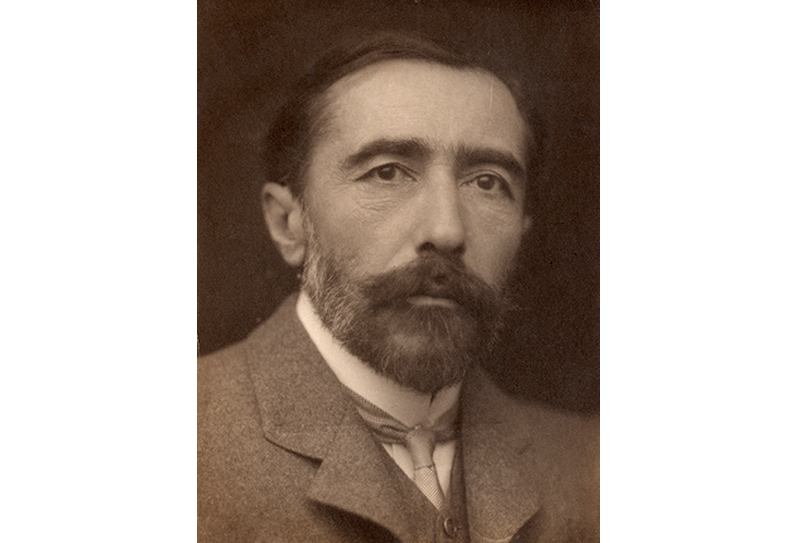

Although Conrad did not spend much time in this region, it made a deep impression on him; about half of everything he wrote revolves around this part of the world. This includes five novels and more than a dozen short stories and novellas. Many of them were directly based on his experience as first mate on a ship that sailed regularly from Singapore to a small trading post about 48 km up the Berau River on the east coast of Borneo between 1887 and 1888.

The people, places and events Conrad encountered in the region come alive in works like Almayer’s Folly (1895), The Outcast of the Islands (1896), Lord Jim (1900), Victory (1915) and The Rescue (1920). It is his excellent visual memory of people, landscape, estuaries, rivers, climate, jungle foliage, commerce, local politics, religion and dress that bring his fictional world to life.

Sojourn in Singapore

Conrad first set foot on Singapore’s shores in 1883. At the time, he was the second mate on the Palestine, which was carrying coal from England to Bangkok. The ship set off from Newcastle in November 1881 but while crossing the English Channel, the Palestine met strong winds and started to leak. It limped back to Falmouth in Cornwall for repairs and finally left for Bangkok on 17 September 1882. Unfortunately, in March 1883, its cargo of coal caught fire and the ship sank near Sumatra. The officers and crew were rescued and taken to Singapore on the British steamship Sissie.1 Here, the Sissie joined the forest of masts anchored in New Harbour (renamed Keppel Harbour in 1900) while around them were hundreds of Chinese tongkangs (a small type of boat used to carry goods along rivers) and Malay prows unloading goods from trading vessels.

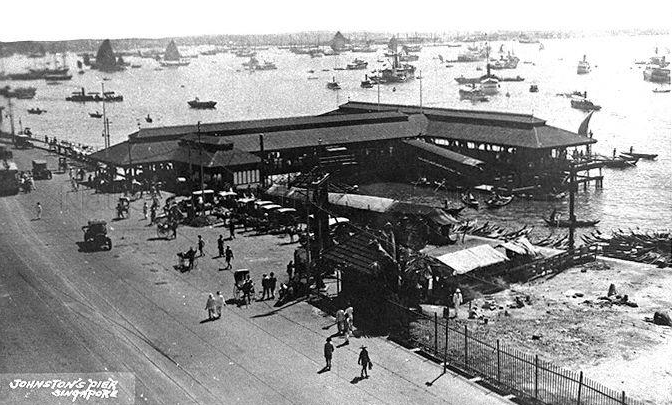

This was Conrad’s first view of Singapore. Before him was Johnston’s Pier, the Master Attendant’s Office, the entrance to the Singapore River and warehouses filled with goods that were in transshipment to the Malay Peninsula, Borneo, the Dutch East Indies and Hong Kong. In the centre was Fort Canning Hill (the former Government Hill). Below that lay the European town, the mansions of prominent European merchants and St Andrew’s Cathedral.

Singapore is the “Eastern port” referred to in Lord Jim, The End of the Tether (1902) and The Shadow-Line (1917), even though Conrad never names the port. In The End of the Tether, Captain Henry Whalley of the steamer Sofala describes the busy harbour with the ships and the Riau Islands in the background:

“Some of these avenues ended at the sea. It was a terraced shore, and beyond, upon the level expanse, profound and glistening like the gaze of a dark-blue eye, an oblique band of stippled purple lengthened itself indefinitely through the gap between a couple of verdant twin islets. The masts and spars of a few ships far away, hull down in the outer roads, sprang straight from the water in a fine maze of rosy lines pencilled on the clear shadow of the eastern board.”2

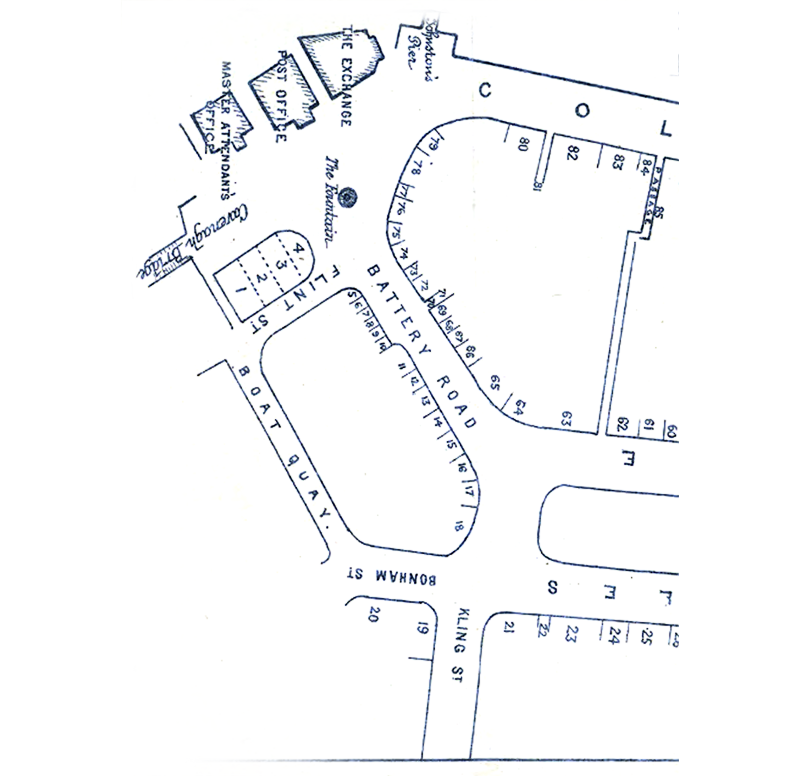

Close to the Master Attendant’s Office was Emmerson’s Tiffin Rooms on Flint Street, which drew sailors, merchants and visitors to its daily lunch menu. It advertised a Tiffin à la carte that is best described as Mulligatawny soup and a Malay chicken curry and rice. These men liked the noisy camaraderie of the place, where patrons exchanged tales of ships, sailors, disasters at sea, piracy, and the latest rumours.

At the junction of Flint Street and Battery Road was the ship chandler McAlister and Company. A vast cavern-like space, the store contained every sundry item that a ship needed to put to sea.

Records show that Conrad was discharged from the Palestine on 3 April 1883 and he remained in Singapore for the whole of April while waiting for a passage back to England. He would have stayed in the Officers’ Sailors Home on High Street, behind St Andrew’s Cathedral, until he embarked on his return passage in May that year.

In The Shadow-Line, he describes the home, which he refers to as the Officers’ Home, as a “large bungalow with a wide verandah and a curiously suburban-looking little garden of bushes and a few trees between it and the street. That institution partook somewhat of the character of a residential club, but with a slightly Governmental flavour about it, because it was administered by the Harbour Office. Its manager was officially styled Chief Steward”.3

Conrad also frequented the port area, including the various cafes and bars where seamen congregated to swap stories and compare voyages.4 It is likely that while waiting to return to England in 1883, he would have become acquainted with the scandal around the pilgrim ship Jeddah, whose events provided the inspiration for the setting of Lord Jim.

While bringing close to 1,000 Muslim pilgrims from Singapore and Penang to Mecca in 1880, the Jeddah ran into trouble and began taking in water. The ship’s captain and some of the officers escaped in a lifeboat, leaving behind all the passengers on board. The captain and the officers were subsequently rescued and brought to Aden, in Yemen, where the captain claimed that the Jeddah had sunk with all lives lost. Fortunately for the passengers, but unfortunately for the captain, the Jeddah did not sink. Instead, it was rescued by a passing ship and towed to Aden, where it arrived a few days after the rescued captain and officers. The captain’s deception was thus exposed and the fact that the captain had abandoned his passengers and lied about the sinking caused an enormous scandal.

In Lord Jim, a pilgrim ship named the Patna undergoes a similar experience and the incident becomes the talk of the town. In the novel, Conrad writes: “The whole waterside talked of nothing else… you heard of it in the harbour office, at every shipbroker’s, at your agent’s, from whites, from natives, from half castes, from the very boatmen squatting half-naked on the stone steps as you went up.”5

The events around the Patna scandal sets the stage for introducing the main protagonist of the novel, the first mate named Jim, who escapes with the captain and subsequently lives with the guilt and shame of his actions. Jim, himself, has a real-life analogue in the first mate of the Jeddah, Augustine “Austin” Williams, who joined the captain in abandoning the ship. After the inquiry, Williams remained in Singapore and worked as a water clerk for McAlister and Company.

Return to Southeast Asia

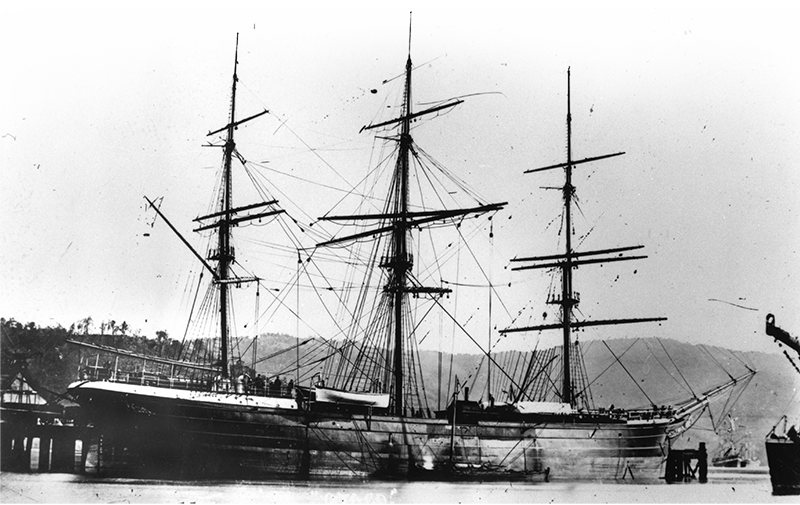

In February 1887, Conrad signed on as first mate of the Highland Forest, a three-masted barque of a little over 1,000 tons. It was berthed in Amsterdam while waiting to load general cargo for a voyage to the port of Semarang on the north coast of Java.

It was a rough voyage and Conrad met with an accident when one of the minor spars (used in the rigging of a sailing vessel to support its sail) fell against his back and sent him sliding on his face along the main deck for a considerable distance. In Lord Jim, Jim suffers a similar accident, and as a result, Jim “spent many days stretched on his back, dazed, battered, hopeless, and tormented as if at the bottom of an abyss of unrest. He did not care what the end would be, and in his lucid moments overvalued his indifference”.6

As Conrad’s injuries persisted even after the Highland Forest had unloaded its cargo in Semarang in June 1887, he reported to the Dutch doctor there that he was experiencing “inexplicable periods of powerlessness and sudden accesses of mysterious pain”. The doctor told him that the injury could remain with him for his entire life. He said: “You must leave your ship; you must be quite silent for three months – quite silent.”7

Conrad was discharged from the Highland Forest on 1 July 1887 and sent on the next ship for hospitalisation in Singapore. Here, he was registered at the hospital as a “Distressed British Seaman” to recuperate. In The Mirror of the Sea, a collection of autobiographical essays, Conrad describes what it was like lying on his back in a Far Eastern hospital and having “plenty of leisure to remember the dreadful cold and snow of Amsterdam, while looking at the fronds of the palm-trees tossing and rustling at the height of the window”.8 Conrad’s experience is the likely inspiration for the scene in Lord Jim when the young seaman recuperates in a hospital in that unnamed Eastern port:

“The hospital stood on a hill, and a gentle breeze entering through the windows, always flung wide open, brought into the bare room the softness of the sky, the languor of the earth, the bewitching breath of the Eastern waters. There were perfumes in it, suggestions of infinite repose, the gift of endless dreams. Jim looked every day over the thickets of gardens, beyond the roofs of the town, over the fronds of palms growing on the shore, at that roadstead which is a thoroughfare to the East, – at the roadstead dotted by garlanded islets, lighted by festal sunshine, its ships like toys, its brilliant activity resembling a holiday pageant, with the eternal serenity of the Eastern sky overhead and the smiling peace of the Eastern seas possessing the space as far as the horizon.”9

As soon as he could walk unaided, Conrad checked out of the hospital for a further period of rehabilitation and to look for a berth back to England. While waiting, he stayed in the Officers’ Sailors Home again and spent time with the other seamen in the port.

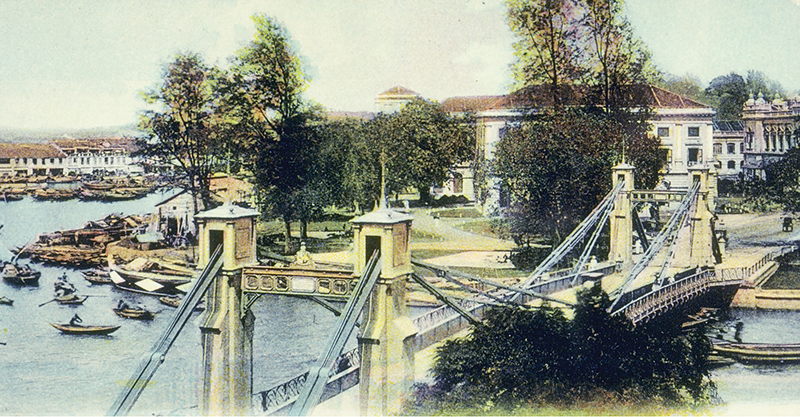

Once Conrad had fully recovered, he would walk daily from the Officers’ Sailors Home towards the Master Attendant’s Office to look for a passage home. Along the way, he would have passed the white spire of St Andrew’s Cathedral, the frontages of the new government buildings, the famous Hotel de l’Europe (site of the former Supreme Court building and part of the National Gallery Singapore today) and along the shaded Esplanade with its enormous trees towards the Singapore River. He would then cross Cavenagh Bridge to reach the Master Attendant’s Office at the other end of the bridge.

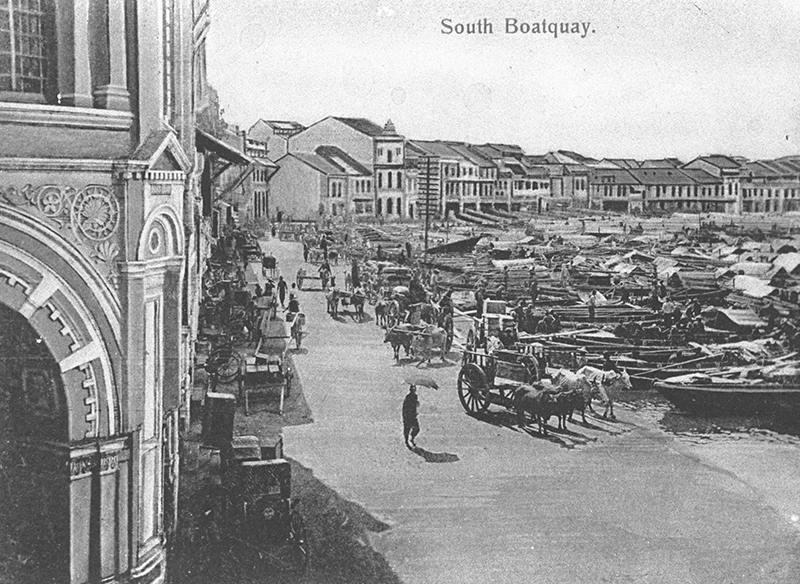

Cavenagh Bridge, opened in 1869, straddled the entrance to the Singapore River and provided one of the most famous views of Singapore. In the late 19th century, Boat Quay would have been packed with a myriad of lighters, tongkangs and sampans bringing goods and people onto the river. The crescent of buildings and warehouses along the quay was taken up with the unloading and loading of these boats. Hundreds of coolies unloaded huge crates, casks, boxes and bales of British manufactured goods into the warehouses, followed by the loading of bales of gambier, bundles of rattans, and bags of tin, sago, tapioca, rice, pepper and spices for export to foreign markets. Conrad describes this scene in his book, The Rescue:

“[O]ne evening about six months before Lingard’s last trip, as they were crossing the short bridge over the canal where native craft lay moored in clusters… Jӧrgenson pointed at the mass of praus, coasting boats, and sampans that, jammed together in the canal, lay covered with mats and flooded by the cold moonlight, with here and there a dim lantern burning amongst the confusion of high sterns, spars, masts, and lowered sails.”10

Voyages on the Vidar

In August 1887, Conrad was hired as first mate on the trading ship Vidar. He found the vessel berthed at the Tanjong Pagar docks, a squared-off compound of warehouses, coal sheds and workshops. According to the Singapore and Straits Directory, its owner, Syed Mohsin Bin Salleh Al Jooffree, also owned several other steamers.11

The Vidar was a picturesque old steamship with a colourful crew, and its captain, James Craig, had sailed the local waters for the last 10 or 12 years and knew them like the back of his hand. Not only did he have to navigate an often dangerous archipelago, filled with marauding pirates and treacherous rivers, he also had to deal with local traders – Dutch, English, Chinese, Arab, Malay and Bugis – in each of these unusual ports. Besides the captain and the first mate, there were two European engineers, a Chinese third engineer, a Malay mate, a crew of 11 Malays, as well as a group of Chinese coolies who worked as deckhands for the loading and unloading of cargo.12

This was a microcosm of the people of the archipelago and they would all have communicated in bazaar Malay which was the commonly used trading language of the region. Already an accomplished linguist, Conrad would have quickly picked up a good knowledge of Malay and this would have brought him into direct contact with the people he later describes in his books.

On the Vidar, Conrad makes four voyages from Singapore to the Berau River in Borneo before signing off from the ship on 4 January 1888. He lowered himself and his seabag into a sampan in the harbour and was rowed ashore to Johnston’s Pier from where he took a horse-drawn cab to the Officers’ Sailors Home.

He had just given up a good berth and a comfortable life in a fine little steamship with an excellent master. However, Conrad’s ambition was to command a sailing ship, a square rigger, not in the comfortable waters of the East Indies, but on the great oceans of the world. In The Shadow-Line, which is based on Conrad’s own experience of his first command, the protagonist, who was accompanied by his captain, describes a similar event, of signing off from a ship, as taking place in the Harbour Office, in a “lofty, big, cool white room” where everyone is in white.

“The official behind the desk we approached grinned amiably and kept it up till, in answer to his perfunctory question, “Sign off and on again?” my Captain answered, “No! Signing off for good.” And then his grin vanished in sudden solemnity. He did not look at me again till he handed me my papers with a sorrowful expression, as if they had been my passports for Hades. While I was putting them away he murmured some question to the Captain, and I heard the latter answer good-humouredly: “No. He leaves us to go home.” “Oh!” the other exclaimed, nodding mournfully over my sad condition.”13

Commanding the Otago

Conrad was ashore for two weeks when he received a message on 19 January 1888 that the Harbour Master would like to see him urgently. The Harbour Master explained that the master of a British ship, the Otago, had died in Bangkok and the Consul-General there had cabled him to request for a competent man to take command.14 Since Conrad already had his Master’s ticket, the Harbour Master gave him an agreement which read:

“This is to inform you that you are required to proceed in the S.S. Melita to Bangkok and you will report your arrival to the British Consul and produce this memorandum which will show that I have engaged you to be the Master of the Otago.”15

Conrad would undoubtedly have been thrilled by this twist of fate. Perhaps he felt the same way the protagonist did in The Shadow-Line, who likewise had just been given his first command:

“And now here I had my command, absolutely in my pocket, in a way undeniable indeed, but most unexpected; beyond my imaginings, outside all reasonable expectations, and even notwithstanding the existence of some sort of obscure intrigue to keep it away from me. It is true that the intrigue was feeble, but it helped the feeling of wonder – as if I had been specially destined for that ship I did not know, by some power higher than the prosaic agencies of the commercial world.”16

The Melita was leaving for Bangkok that evening and Conrad would be on it. He arrived in Bangkok on 24 January 1888 and as the coastal steamer came up the river, its captain was able to point out Conrad’s new ship. The lines of its fine body and well-proportioned spars pleased Conrad immensely as this was a high-class vessel, a vessel he would be proud to command.

After almost two years away, Conrad returned to London in May 1889, idle and without a ship. His memory and imagination returned to Singapore and the Malay Archipelago, and he began writing a novel based on his voyages from Singapore on the Vidar. As he wrote in his autobiographical work, A Personal Record (1912), the characters from his time on the Berau River began to visit him while he was in-between work in London:

“It was in the front sitting-room of furnished apartments in a Pimlico square that they first began to live again with a vividness and poignancy quite foreign to our former real intercourse. I had been treating myself to a long stay on shore, and in the necessity of occupying my mornings, Almayer (that old acquaintance) came nobly to the rescue. Before long, as was only proper, his wife and daughter joined him round my table and then the rest of that Pantai band came full of words and gestures. Unknown to my respectable landlady, it was my practice directly after my breakfast to hold animated receptions of Malays, Arabs, and half-castes.”17

These characters and places eventually end up populating Almayer’s Folly, Conrad’s first novel. Published in 1895, the work would launch Conrad’s career as a writer. He would go on to draw upon his experiences in the Malay world in subsequent novels and short stories. Along the way, he helped craft a particular image of Singapore, the Malay Archipelgo and the Dutch East Indies in the imagination of the reading public.

Ian Burnet is the author of Joseph Conrad’s Eastern Voyages – Tales of Singapore and an East Borneo River (2021). He is also the author of Archipelago – A Journey Across Indonesia (2015), and Where Australia Collides with Asia – The Epic Voyages of Joseph Banks, Charles Darwin, Alfred Russel Wallace and the Origin of On the Origin of Species (2017).

Ian Burnet is the author of Joseph Conrad’s Eastern Voyages – Tales of Singapore and an East Borneo River (2021). He is also the author of Archipelago – A Journey Across Indonesia (2015), and Where Australia Collides with Asia – The Epic Voyages of Joseph Banks, Charles Darwin, Alfred Russel Wallace and the Origin of On the Origin of Species (2017).NOTES

-

Tim Middleton, Joseph Conrad, Routledge Guides to Literature series (New York: Routledge, 2006), 172, https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.4324/9780203603055/joseph-conrad-tim-middleton. ↩

-

Joseph Conrad, Tales of an Eastern Port: The Singapore Novellas of Joseph Conrad (Singapore: NUS Press, 2023), 19. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 823.912 CON) ↩

-

Conrad, Tales of an Eastern Port, 124. ↩

-

Jerry Allen, The Sea Years of Joseph Conrad (London: Methuen, 1967), 148. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 823.912 CON-[JSB]) ↩

-

Joseph Conrad, Lord Jim (Edinburgh & London: William Blackwood and Sons, 1914), 36. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 823.912 CON-[JSB]) ↩

-

Joseph Conrad, The Works of Joseph Conrad: The Mirror of the Sea; a Personal Record (London, Toronto: J.M. Dent & Sons Ltd., 1923), 54–55. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 823.912 CON-[JSB]) ↩

-

Conrad, The Works of Joseph Conrad: The Mirror of the Sea; a Personal Record, 55. ↩

-

Joseph Conrad, The Rescue: A Romance of the Shallows (London; Toronto: J.M. Dent & Sons Ltd., 1920), 95. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 823.912 CON-[SEA]) Norman Sherry, “Conrad and the S.S.Vidar,” Review of English Studies 14, no. 54 (May, 1963): 158. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Norman Sherry, “Conrad and the S.S.Vidar,” Review of English Studies 14, no. 54 (May, 1963): 158. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

“Vidar,” Tyne Built Ships, last accessed 30 November 2023, http://www.tynebuiltships.co.uk/V-Ships/vidar1871.html. ↩

-

Conrad, Tales of an Eastern Port, 123–24. ↩

-

Conrad, Tales of an Eastern Port, 139. ↩

-

Norman Sherry, “‘Exact Biography’ and The Shadow-Line,” PMLA 79, no. 5 (December 1964): 620–25. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website); “Joseph Conrad Collection,” Archives at Yale, last accessed 3 January 2024, https://archives.yale.edu/repositories/11/resources/588. ↩

-

Conrad, Tales of an Eastern Port, 142. ↩

-

Joseph Conrad, A Personal Record (La Guerche-sur-l’Aubois: eBooksLib, 2005). (From NLB OverDrive) ↩