Cikgu Asfiah Abdullah: A Cultural Luminary

A former teacher and mak andam fulfils her dream by writing a book on Malay recipes in 1986, the first all-Malay cookbook from Times Books International.

By Toffa Abdul Wahed

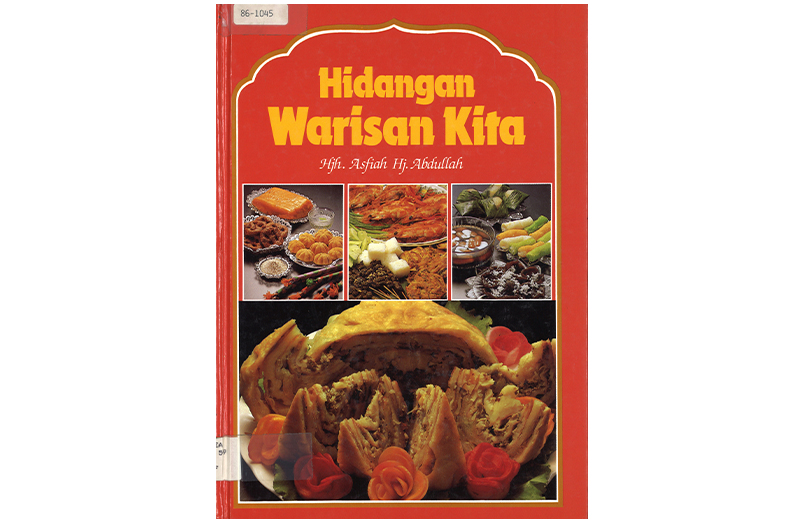

In 1986, a cookbook titled Hidangan Warisan Kita (Our Heritage Dishes) was published by Times Books International. Written by Hajah Asfiah Haji Abdullah,1 a matriarch revered for her expertise in the cultural arts, the book was priced at $18 and showcased 178 recipes for a wide array of traditional Malay food,2 namely kuih-muih (an assortment of sweet or savoury snacks), noodles, rice, accompaniments to rice (lauk-pauk) and gubahan (elaborately prepared dishes for special occasions such as weddings and engagement ceremonies).3

In her preface, Asfiah invited readers to embark on a journey to discover the authentic ways of preparing traditional Malay dishes. “I sincerely hope that with the publication of this book, all our heritage cuisines and dishes will continue to be cherished, not lost to time, and will become a treasure in our kitchens for generations to come,” she wrote.4

This book represented many firsts. It was the first time that Times had published a cookbook written in the Malay language by a Malay author, and in doing so, the publisher had put Asfiah in the company of familiar household names like Terry Tan and Betty Yew, who had written several cookbooks about Singaporean cuisine, Malaysian cuisine and Peranakan Chinese cuisine for the same publisher.5

After the book was published, Straits Times journalist Haron Abdul Rahman noted that this was possibly the first of its kind – a Malay cookbook in hardcover no less. This achievement was, he suggested, not so surprising given that “Hajah Asfiah Haji Abdullah, the authoress of Hidangan Warisan Kita, is a rare woman where preserving Malay heritage and upholding Malay culture and traditions are concerned”.6

A Champion of Malay Culture, Tradition and Artistry

Born in 1920 in Kampong Gelam, Asfiah began learning the art of making Malay kuih from her mother when she was just 6 years old. She also helped out at her mother’s food stall in front of their house on Bussorah Street, directly behind Sultan Mosque, during the Muslim fasting month of Ramadan. “My mother taught me how to bake Malay cakes which she herself was very good at. Then I was sent to Rochore Malay Girls’ School, where I learnt handicrafts like embroidery and flower-making,” she told the Straits Times in an interview in June 1986.7

The skills that Asfiah acquired in school further enriched her repertoire. In 1931, after completing Standard Four at age 10, she began teaching Malay handicrafts at the school. “It was difficult at first,” she said. “Many of the girls were only a year younger than me and I could not control them sometimes. I kept having to go to the headmistress for help.”8 Despite her initial challenges, Asfiah found joy in teaching and continued to impart her skills and knowledge to others throughout her life.

After her mother’s death, Asfiah took over the business and the stall remained a regular fixture at the annual food fair in Kampong Gelam. During this time, Bussorah Street would be lined with rows of makeshift stalls that attracted people from all over Singapore for the delicious food. She enticed customers with a smorgasbord comprising kuih and dishes like mee siam and laksa. In 1980, Asfiah passed the torch of running the business to her daughters, Salamah, Rasidah and Masita, but continued to help in the preparation of the kuih.9 Later, her youngest son also took an interest in learning to run her kuih and tekat (a type of traditional Malay embroidery used to decorate ceremonial items made of velvet with designs created using gold threads) business.10

Known affectionately as Cikgu Asfiah (cikgu in Malay is a title for teacher), she dedicated her life to serving the community and imparting her vast knowledge of Malay culture to the younger generations through not only her cookbook but also via classes at her home on Bussorah Street, demonstrations, talks and exhibitions. The publication of Hidangan Warisan Kita was her crowning achievement, but her contributions to the Malay community extended beyond the culinary realm.

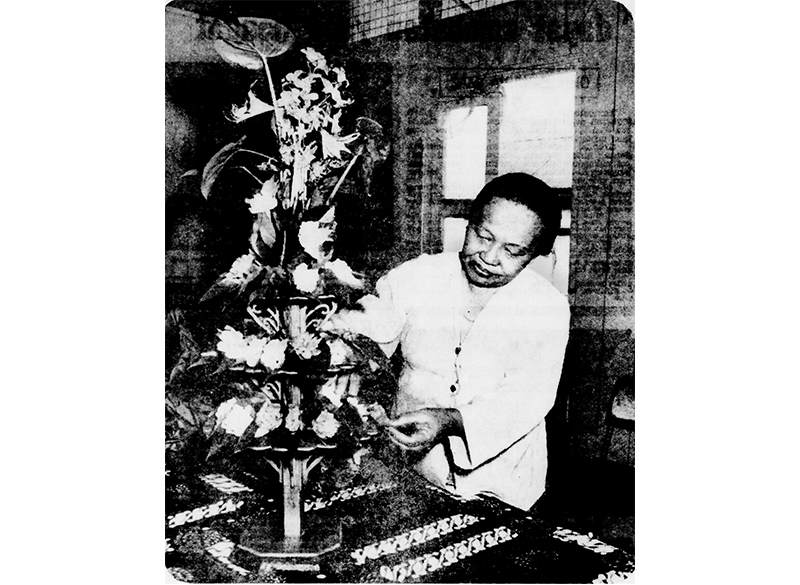

Asfiah was also renowned for her expertise in Malay wedding customs, needlework and flower arrangement as well as traditional skincare, makeup and hairdressing. Although Asfiah made her income from teaching the cultural arts, she firmly believed that it was her duty and responsibility to pass on her knowledge to young Malay girls and women.

Margaret Sullivan, who featured a chapter about Asfiah and the kuih trade in her book, “Can Survive, La”: Cottage Industries in High-rise Singapore (1985), hailed her as a “teacher and guardian for [sic] traditional Malay culture in Singapore”. Asfiah “[saw] herself as an articulator of traditional values with almost a ‘mission’ to pass on the knowledge before ‘Malayness’ was [lost]”.11 In 1987, a journalist with the Berita Harian newspaper described Asfiah as an “activist of Malay handicrafts”, highlighting her unwavering commitment to preserving Malay culture.12

Asfiah developed a profound interest in kesenian Melayu lama (traditional Malay arts), including bridal wear, dressing up the wedding dais and floral decorations for the matrimonial bed. She was, however, unable to devote much time to this interest. In 1949, having retired from teaching after almost two decades, she wasted no time in becoming a mak andam.13 The role of a mak andam holds significant cultural importance in Malay weddings. Their duties traditionally involve beautifying the bride, as well as guiding the bride and groom through various rites and ceremonies that take place before, during and after the wedding.14

Asfiah went on to become a well-known and esteemed mak andam, a role that she performed for some 20 years. “I must have been a Mak Andam for more than 1,000 brides,” she told the Straits Times in 1986. “I have many fond memories of these occasions, like when I refused to let the best man bring in the groom unless he could answer my pantun (rhyming riddle).” She revealed there had been instances when the best man became so irritated that he would stomp off, leaving the hapless groom behind.15

Asfiah’s remarkable skills and knowledge as a mak andam also led to numerous engagements and invitations from cultural organisations. These include Persatuan Kebudayaan Melayu Singapura (PKMS; Society of Malay Culture, Singapore) and Majlis Pusat Pertubuhan-Pertubuhan Budaya Melayu Singapura (Central Council of Malay Cultural Organisations Singapore), who recognised her as a valuable advocate for preserving Malay heritage and culture.

Membership in Malay Organisations and Associations

Asfiah’s involvement in PKMS dates back to the early 1960s when she joined as a dedicated member. She was elected as the vice-chairperson in 1971, making her the sole female member on the executive committee at the time. This role allowed her to work alongside prominent figures within the Malay community, including Mahmud Ahmad, the chairperson, and Abdul Ghani Hamid, the secretary.16

Notably, in 1973, Asfiah played a pivotal role in the establishment of the Women’s Wing of PKMS, which aimed to promote and advance traditional handicrafts among local women. She was also elected as its vice-chairperson.17

Within PKMS, one of her major contributions was a regular course she ran for women titled “Seni Usaha Daya” (The Art of Effort and Ability) at Jalan Eunos in the early 1970s. The course, which was offered at $30 and open to the public, consisted of 12 weekly classes on Malay handicrafts, including embroidery and needlework, flower arrangement, making flowers from craft materials, and arranging the tepak sirih (ceremonial betel box used in Malay weddings) and sirih dara (an arrangement of betel leaves and flowers to symbolise a bride’s chastity). Every participant received a certificate upon passing the course.18

The course revived interest in Malay traditional arts and empowered the participants, many of whom subsequently pursued a career as a mak andam. The popular course could have as many as 100 students. Most of those who enrolled were housewives.19

The PKMS also organised exhibitions showcasing the students’ handiwork. For instance, after the completion of a course in 1972, Asfiah hosted a small exhibition at her residence which ran for two days. Visitors lauded the women’s resourcefulness in producing captivating works on a budget. In an interview with Berita Harian, Asfiah reiterated that there was a need to pass down ancestral knowledge to younger generations, as many lacked the skills to create these traditional pieces particularly items for weddings. She emphasised the rarity of such items and proposed updating them to appeal to modern tastes, especially tourists unfamiliar with these cultural treasures.20

Asfiah’s association with Majlis Pusat and its women’s department began in the early 1980s. Despite not holding any leadership positions in this organisation, she participated in numerous activities from conducting classes on the cultural arts to organising exhibitions, just like she did with PKMS.

In 1981, she had about 30 of her sanggul (embellished hairbun) creations displayed in an exhibition by Majlis Pusat titled “Pameran Seni Budaya” (Cultural Arts Exhibition) held at the National Museum. The exhibition was one of the programmes offered as part of the inaugural Pesta Budaya Melayu (Malay Culture Festival), also organised by Majlis Pusat, from 6 to 15 March. It was touted as the “first large-scale Malay cultural festival in Singapore”.21

Kasminah Bakron, a 24-year-old clerk who visited the exhibition, was amazed by the artistry of the products and went on to enrol in a course taught by Asfiah and organised by the women’s wing of Majlis Pusat. She said: “Saya terpesona melihat kehalusan orang-orang Melayu lama dalam kerja-kerja tangan seperti menggubah, tekad-menekad [sic] dan adat-adat lain, seperti bilik pengantin, yang kita mungkin tidak tahu erti sebenarnya jika tidak mengikuti kursus seperti ini.” (“I am fascinated by the finesse of the Malays from the older generations in handiwork such as flower arrangement, tekat and other customs, such as [those related to] the bridal chamber, which we may not truly understand if we do not attend courses like this.”)22

A Dream Come True

Since the 1970s, Asfiah had been advocating for books to be written on various aspects of Malay culture. Speaking at a Hari Raya Aidilfitri gathering organised by the women’s wing of Majlis Pusat in August 1980, Asfiah emphasised the need to document the types and methods of cooking Malay dishes, and preserve traditional makeup techniques to ensure that traditions of the Malay community would not fade into obscurity. She said: “Kalau wanita-wanita muda hari ini tidak mahu belajar cara masakan kita kerana dianggapnya leceh, maka dengan sendirinya masakan Melayu akan hilang ditelan zaman.” (“If young women today do not wish to learn [how to cook] our dishes because they perceive them as troublesome [to make], then on its own Malay cuisine will be lost to time.”)23

Asfiah had wanted to publish a Malay cookbook for many years before her dream came true in 1986. “I have always wanted to place on record some aspects of Malay culture, such as our food and customs. This is a chance to keep some of this for posterity,” she said in an interview.24

Prior to Hidangan Warisan Kita, Berita Harian reported in July 1971 that Asfiah had compiled three manuscripts aimed at providing general guidance to women.

The first, titled Seni Usaha (The Art of Effort), has instructions on creating handmade items and is accompanied with illustrations. The second, Seni Usaha Daya (The Art of Effort and Ability), delves into the realm of handicrafts and household management. The last, Seni Ayu Pusaka Ibu (Gentle Art Inherited from Mothers), is a tribute to ancestral art and values.25 It is likely that Asfiah never got a publisher for these manuscripts, or that they were only reproduced cheaply for use in her classes as teaching aids.

Speaking to the Straits Times in August 1986, Asfiah said with tears in her eyes: “I feel very sad when I see my former students compiling recipes and selling them in a cyclostyled booklet form. How long can such booklets last? How effective are such efforts? No, that wouldn’t do. A book has to be published, preferably with a hard cover, so as to give such efforts a chance for permanency.”26

Asfiah began writing Hidangan Warisan Kita in 1984. On top of facing difficulties typing and concentrating due to her age, she also could not find help initially in the writing of the manuscript. Her family eventually played a crucial role in bringing her dream to fruition when her daughter Salamah, son Khairul Anuar and grandson Asrin, became involved in the book’s production. Margaret Sullivan’s feature about Asfiah in her book also caught the attention of Times Books, which eventually became her publisher, leading to the realisation of her dream at the age of 65.27

In her dedication, Asfiah wrote: “Buat suami, anak-anak dan cucu-cucu yang banyak memberi perangsang dan galakan dan buat semua anak bangsa yang gemarkan masakan tradisi kita.” (“[To] my husband, children and grandchildren who had given me a lot of encouragement and to all Malays who love our traditional cuisine.”)28 Slightly more than a year after the publication of the book, Asfiah died at her home on Bussorah Street in August 1987.29 Through her perseverance and dedication, Asfiah’s dream of sharing her heritage with future generations lives on in the pages of Hidangan Warisan Kita.

On 8 October 1985, Hasnah Ani and Amanah Mustafi, scriptwriters with the former Singapore Broadcasting Corporation, interviewed Asfiah Abdullah for a television programme. They asked her various questions about Malay customs, ranging from engagement ceremonies and wedding customs to customary feasts. She talked about customs she was very familiar with such as being a mak andam, suap-suapan (the bride and groom feeding each other yellow glutinous rice), khatam quran (completion of Quran recitation) and makan berdamai (bride and groom eating together).

Asfiah also shared her expertise on a variety of Malay dishes, how to make them and how they had evolved over time. The dishes mentioned include kuih coro (also known as kuih bakar manis), kuih telumba, kuih selang madu nikmat (also known as baulu terenang), sambal goreng pengantin, serondeng (dendeng ageh), rojak and nasi rampadan.

The National Library of Singapore has the nine-page interview transcript (in Malay) in its holdings, thanks to the kind donation by Amanah Mustafi who still works in television and broadcasting today. If you wish to read the transcript, do make a request at Level 11 of the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library, National Library Building.

REFERENCE

The transcript titled “Temuramah dengan Che Asfiah Abdullah Tentang Serba Sedikit Adat-adat Melayu Serta Jenis-jenis Makanannya” (Interview with Madam Asfiah Abdullah regarding some Malay customs and types of food] is kept under this record: The Malay Costume (1959–1983/4); Asal Usul Brunei; Jalan-Jalan Cari Makan Jakarta; Research on the Malays in Sri Lanka, manuscript. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 305.89928 MAL)

Toffa Abdul Wahed is a Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. She works with the Singapore and Southeast Asia Collection.

Toffa Abdul Wahed is a Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. She works with the Singapore and Southeast Asia Collection.Notes

-

Her name has also been spelled “Aspiah”. For this article, I have used “Asfiah” which is how it is spelt in her cookbook. The honorific “Hajah” (or “Hajjah”) and “Haji” are titles given to women and men respectively who have performed the pilgrimage to Mecca. I am using the current spelling “Hajah”, which is recommended by Kamus Dewan, 4th edition (Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, 2005). ↩

-

Malay food here refers to dishes from various communities and subgroups found within the Malay ethnic group. Immigrants from other parts of the Nusantara (the Malay World), such as Java, Sumatra, Sulawesi, Banjar and Malaya, came to trade, work as well as settle in the bustling, cosmopolitan port of Kampong Gelam. Asfiah herself was of Javanese descent. ↩

-

According to food writer and cooking instructor Christopher Tan, the word kueh or kuih refers to a diverse variety of sweet and savoury foods and snacks. Kuih is the formal spelling used in Malay today. See Christopher Tan, The Way of Kueh: Savouring & Saving Singapore’s Heritage Desserts (Singapore: National Heritage Board, 2019), 2. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 641.595957 TAN) ↩

-

Hajah Asfiah Haji Abdullah, Hidangan Warisan Kita (Singapore: Times Books International, 1986), xii. (From National Library, Singapore, via PublicationSG). ↩

-

Ang Lay Wah, “Guardian of Malay Culture,” Straits Times, 1 June 1986, 12. (From NewspaperSG). The English titles published by Times Books International include Terry Tan, Straits Chinese Cookbook (Singapore: Times Books International, 1981). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 641.5929505957 TAN); Betty Yew, Rasa Malaysia (Singapore: Times Books International, 1982). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 641.59595 YEW); Terry Tan, Oriental Kitchen (Singapore: Times Books International, 1982). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 641.595 TAN); Terry Tan, Cooking with Chinese Herbs (Singapore: Times Books International, 1983). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 641.5951 TAN); and Wendy Hutton, Singapore Food (Singapore: Times Books International, 1989). (From National Library, Singapore, via PublicationSG) ↩

-

Haron Abdul Rahman, “A Dream Comes True for ‘Guardian of Culture’,” Straits Times, 14 August 1986, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Ang, “Guardian of Malay Culture.” ↩

-

Ang, “Guardian of Malay Culture.” ↩

-

Zakaria Buang, “Suasana Bussorah St Tak Semeriah Dulu?” [Atmosphere of Bussorah St is not as lively as it used to be?], Berita Harian, 27 July 1980, 2; “‘Food Fair’ Street Springs to Life Again at Ramadan,” Straits Times, 16 August 1978, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Ang, “Guardian of Malay Culture.” ↩

-

Margaret Sullivan, “Can Survive, La”: Cottage Industries in High-Rise Singapore (Singapore: G. Brash, 1985), 55–56. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 338.634095957 SUL) ↩

-

“Asfiah Meninggal,” [Asfiah dies], Berita Harian, 5 August 1987, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Zawiyah Salleh, “Pertunjokan Pakaian Pengantin Wanita Melayu 1800 Menarek Penonton2,” [Show of Malay bridal attire from 1800 attracts audiences], Berita Harian, 2 April 1972, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

For more information about Malay wedding customs, see Asrina Tanuri and Nadya Suradi, “Malay-Muslim Weddings: Keeping Up with the Times,” BiblioAsia 17, no. 2 (July–September 2021): 16–21. ↩

-

Ang, “Guardian of Malay Culture.” ↩

-

“PKMS Tak Jadi Keluar Dari MPH Tetapi Ada Sharat,” [PKMS did not leave MPH but had conditions], Berita Harian, 6 April 1971, 2. (From NewspaperSG). PKMS was registered as a society on 5 August 1953. Founding members include Othman Kalam (advisor), Harun Aminurrashid (president), Othman Haji Omar (vice-president) and Sufiah Yusof (vice-president). For more information on PKMS and its founding, see Persatuan Kebudayaan Melayu Singapura, Siri Budaya (Singapore: Pustaka Melayu, 1960), 45. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.5 PER) ↩

-

Zawiyah Salleh, “Badan Wanita Bagi Majukan Seni Kerajinan Tangan,” [Women’s body to advance the art of handicrafts], Berita Harian, 23 September 1973, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Maniseh Haji Siraj, “Chinta Terhadap Seni Pusaka Bangsa Menjadi Darah Daging Chegu Aspiah Abdullah,” [Love towards Malay heritage art becomes part of Chegu Aspiah Abdullah], Berita Harian, 18 July 1971, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Seni Usaha Daya Membaharui Barang2 Lama,” [The Art of Effort and Ability updates old things], Berita Harian, 25 April 1972, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Lebih 30 Jenis Pakaian Tradisional Diperaga,” [More than 30 kinds of traditional clothing shown], Berita Harian, 3 March 1981, 3; “1,500 to Take Part in Malay Festival,” Straits Times, 23 February 1981, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Zawiyah Salleh, “Peluang Pelajar Seni Lama Sentiasa Terbuka,” [Opportunities for traditional art students are always open], Berita Harian, 18 July 1981, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Zawiyah Salleh, “Cara Pendidikan Yang Baik Untuk Anak2 Kita,” [Good way of educating our children], Berita Harian, 30 August 1980, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Ang, “Guardian of Malay Culture.” ↩

-

Maniseh Haji Siraj, “Chinta Terhadap Seni Pusaka Bangsa Menjadi Darah Daging Chegu Aspiah Abdullah.” ↩

-

Haron Abdul Rahman, “A Dream Comes True for ‘Guardian of Culture’.” ↩

-

Haron Abdul Rahman, “A Dream Comes True for ‘Guardian of Culture’.” ↩

-

Hajah Asfiah Haji Abdullah, Hidangan Warisan Kita, n.p. ↩