Reconstructing Charles Darwin’s Lost Library

Almost 20 years of painstaking scouring and sleuth work have resulted in what is probably the largest and most comprehensive resource on Charles Darwin.

By John van Wyhe

Charles Darwin (1809–82) is arguably the most influential scientist who ever lived. During his lifetime, he transformed the theory of evolution from ridiculed speculation to an established fact accepted by the international scientific community. The implications of this profound shift in how life on Earth is understood was immeasurable. Discussions of, and reactions to, Darwin remained common for over a century, and not only in biology and palaeontology but also in philosophy, art, literature and much more. Tens of thousands of publications have discussed Darwin’s works in dozens of countries and languages in a continuous stream that has never ceased.

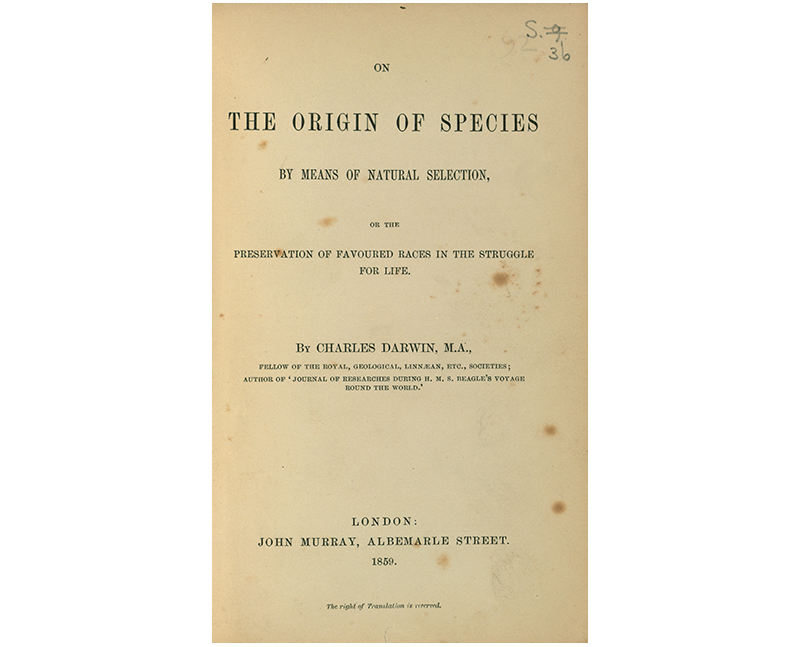

Scholars have been studying Darwin’s life and work ever since On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection was published in 1859, and today, scholarship on Darwin has become a large and sophisticated area of research. Indeed, it is a daunting area for young researchers to enter because the scholarly literature is so vast that it takes years to read and master enough of it to contribute something new. However, despite all this attention on Darwin and his writings, there has been one notable omission: in the 140 years or so since Darwin’s death, a complete list of all the works that he owned, used and cited did not exist.

This gap has finally been filled. After 18 years of painstaking research – involving scouring numerous obscure lists and consulting unusual sources, as well as extrapolating from vague, fragmentary and handwritten notes – we have finally completed the task of cataloguing the contents of Darwin’s enormous library. We now know that Darwin’s library contained 7,494 unique titles across 13,000 volumes/items. Looking at the list, it is clear that Darwin had one of the most extensive and important private scientific libraries of the 19th century.

The research that led us to recreate this library was done as part of the project, The Complete Work of Charles Darwin Online, or Darwin Online for short. Darwin Online has gone beyond merely cataloguing Darwin’s library; it has also reassembled this library virtually, allowing anyone to examine the works in detail. The result is an indispensable tool for scholars, scientists, researchers and students interested in the history of Victorian science.

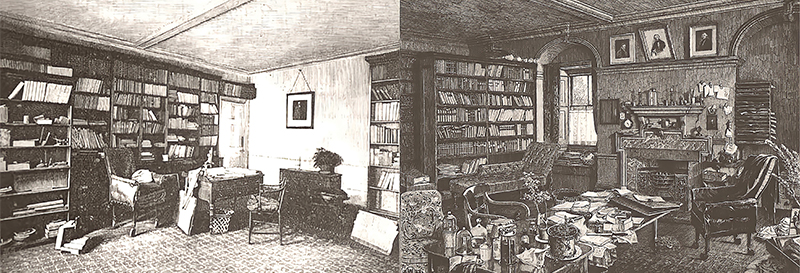

On the Origin of Darwin Scholarship

Large collections of Darwin’s letters were first published by his son Francis in the years after his father’s death in 1882. This was followed by two early drafts of Darwin’s theory of evolution in 1909. About the same time, Francis donated much of his father’s scientific library to Darwin’s (and his) alma mater, the University of Cambridge. A catalogue of these books – but not the journals and pamphlets – was published in 1908. In 1929, Darwin’s family home, Down House, was made a public museum and much of his library was transferred back to its original home. (Down House is located in the London Borough of Bromley; its garden and grounds remain open to the public.)

The modern age of Darwin scholarship is said to have begun with work on the enormous body of Darwin’s manuscripts and private papers acquired by Cambridge University Library in the 1940s. These were broadly catalogued in 1960, and in the mid-1970s, an ambitious project was conceived by Frederick Burkhardt, former president of the American Council of Learned Societies, to publish all the letters from and to Darwin. The 30-volume endeavour, The Correspondence of Charles Darwin, was finally completed in 2023 and published by Cambridge University Press.

Between the 1960s and 1980s, editions of Darwin’s transmutation (evolution) notebooks were published, showing in unprecedented detail the complex gestation of his theories and many of the sources Darwin had drawn from.

In 1990, a volume of the marginalia or annotations in Darwin’s books was published based on the surviving part of Darwin’s library of books housed in Cambridge University Library and Down House. These 1,476 books have since been referred to as “Darwin’s Library”. Having been thus cited and referred to so many times, it has led to the impression that this was the entirety of what Darwin’s library originally contained. Specialist scholars were nevertheless aware that Darwin also had hundreds of volumes of scientific journals and thousands of pamphlets, offprints and book reviews, and these were not on this list of “Darwin’s Library”.

Darwin Online

In 2002, while a research fellow at the National University of Singapore (NUS), far away from my home in Cambridge, I founded a project that is now called Darwin Online. This was a scholarly project whose website would include all of Darwin’s publications, manuscripts, papers, bibliography, and catalogue of manuscripts and associated materials and introductions. From 2005, major funding was provided by the Arts and Humanities Research Council in the UK to expand the project at the University of Cambridge.

The new site was launched in October 2006 and the news went viral. It was mentioned in hundreds of websites and newspapers around the world, and covered by renowned media outlets such as BBC Radio 4’s Today Programme, BBC Breakfast (TV), the regional BBC stations, CNN and The Guardian, etc. Millions of visits to the site brought the servers at Cambridge crashing down multiple times in the first 24 hours. Overnight, Darwin Online had become one of the best-known history of science projects in the world.

That was only the beginning though. Darwin’s manuscripts and private papers were launched in 2008 when 100,000 images from the Darwin Archive in Cambridge became available, and another viral media event followed. Several other viral launches followed over the next few years such as when the diaries of Darwin’s wife, Emma, went online in 2007 for the first time and his newly discovered student bills in 2009.

In 2010, NUS invited me to Singapore to continue my research and zoological historian Dr Kees Rookmaaker, who worked with me on Darwin Online, came with me. Together, we created Wallace Online, a complete edition of the writings of the great naturalist, Alfred Russel Wallace, who explored Southeast Asia between 1854 and1862 and independently came up with a theory of evolution by natural selection similar to Darwin’s.

In 2014, while in Singapore, we reconstructed and put online the entire 400-volume library that had been aboard Darwin’s ship, HMS Beagle. Most of that library’s contents had been reconstructed by the editors of The Correspondence of Charles Darwin. I was able to add more titles from my own research, especially from editing Charles Darwin’s Notebooks from the Voyage of the Beagle, a book published by Cambridge University Press in 2009.

In 2021, reviews of all his books were launched on Darwin Online. Numbering over 1,700 in several languages, it is the largest collection of the reviews of the work of any historical scientist.

Darwin Online also contains the largest collection of, recollections of, and obituaries of any scientist. With all this material, together with his publications (including hundreds of newly discovered shorter items), notebooks and papers, Darwin Online has become what we believe to be the most comprehensive scholarly website on any historical person in the world, with hundreds of editorial introductions and over 15,000 footnotes.

Since 2006, while Kees and I were doing all this, we had also been working on collecting and collating sources that reveal the contents of Darwin’s personal library. Every year, I receive letters and emails asking whether Darwin had this or that book or article in his library. I was able to answer many of these by looking them up in our unpublished lists and notes so I knew there would be value in making this list available online.

Reconstructing Darwin’s personal library, however, was a daunting project to attempt, let alone to complete. There were a huge number of pieces of this puzzle to assemble first; indeed, many more than anyone could have at first imagined or planned for.

In the past, many of Darwin’s books were scattered throughout the stacks at Cambridge University Library and from time to time, their identity and locations were added to various internal lists. Due to the immense kindness and assistance from the former Keeper of Scientific Manuscripts, Adam Perkins, I was given copies of these lists, as well as a list of books at Down House. We were also provided with copies of the library’s unpublished and paper-only catalogue of Darwin’s “unbound materials” by cataloguer Nick Gill. This was a catalogue of 1,700 journals that had never been given a hardback binding.

Cambridge University Library had already given Darwin Online permission to include a copy of a newer item-by-item catalogue of the entire Darwin Archive (over 40,000 items) prepared by Gill. The conversion of that very catalogue to an online database was a major challenge and it took years before the library put it online.

To these, we added the records of Darwin’s items found in over 80 other collections around the world, creating the world’s first union catalogue of Darwin’s papers. This enabled me to generate a list of the printed/published items owned by Darwin – there were more than 3,000. These ranged from newspaper clippings to scientific journals that were filed in his subject-specific research portfolios on particular scientific topics that interested him, such as the geographical distribution of species, the expression of emotions or instincts. It seemed to be an arbitrary decision to include a pamphlet that belonged to Darwin on one shelf as part of his library but to designate another in his papers as not part of the library. I decided from the beginning that these printed items should be counted as part of Darwin’s library too.

Family Documents

Vitally important were the records that Darwin kept of his library as it was in his lifetime. In 1875, he had a handwritten 426-page catalogue, Catalogue of the Library of Charles Darwin, Esq. M.A., F.R.S., of his library prepared by Thomas William Newton, Assistant Librarian of the Museum of Geology. (This was only published in 2011, in Darwin Online.) Going through this independently, Kees and I identified over 400 works that had once been in Darwin’s library but were not in the surviving collections.

In the 1870s, Darwin and his son Francis also prepared catalogues of the thousands of pamphlets, offprints and book reviews in the library. Unlike the leather-bound Catalogue of the Library of Charles Darwin, these catalogues were made mostly from thousands of strips of paper, recording an item in one or two lines, in an extremely abbreviated form. These were transcribed and original entries expanded somewhat by Darwin scholar, P.J. Vorzimmer, in 1963. A photocopy of his work was placed in the Manuscripts Reading room at Cambridge University Library, where it still resides.

I had these catalogues digitised, transcribed and added to Darwin Online. The superb cataloguer Nick Gill produced a far more detailed improvement on Vorzimmer’s catalogue and he generously shared a list of these in 2007. Kees identified many further items and I finished the work in Singapore.

Another valuable source of information came from an inventory of Down House, which was done after Darwin’s death to calculate legacy duty or inheritance tax. With Darwin’s death, his scientific library, mostly in his study, became the property of his son Francis. The books in the drawing room were, however, counted and the titles and number of volumes recorded. This obscure list is known to very few and had also never been utilised in reconstructing Darwin’s library. In it, we find 2,065 bound books scattered around the house and an unknown number of unbound volumes, sundries and pamphlets. And, in a precious piece of good fortune, the books in the drawing room were listed. Little more than an author name and a few words of the title and the number of volumes were recorded but it was enough to add 132 titles and 289 volumes of mostly unscientific literature to the Darwin library catalogue.

Darwin’s wife Emma, who sometimes noted down books to buy in her diary, was another source. From her, 32 titles were added to the list. Many more book titles in her diary do not have prices next to them. No doubt some of these too were purchased, but it is impossible to distinguish them from books she intended to borrow from a library. Other works have been made known to us by owners of private collections.

Besides publishing the letters written to and from Darwin, the editors of The Correspondence of Charles Darwin also listed hundreds of publications in their footnotes that had been sent to or were purchased by Darwin but were no longer extant in the Darwin Library. There were also hundreds of references to items in Darwin’s pamphlet collection, many of which were not found in all the other sources we had already put together.

Finally, with all of this valuable information at my disposal, I sought for evidence of further works owned by Darwin by scouring catalogues of rare-books sales and auctions from the 1890s to the present. This brought a few more unknown titles that Darwin had once owned. In addition, there were other titles to be found mentioned in Darwin’s manuscripts.

After collating and recollating all of these, a second phase of detective work began – to identify all the vague references to authors and titles. Some were unambiguous and easy to fill in, others were extremely obscure or the handwritten reference so illegible that it took many tricks and roundabout methods to identify them. For example, a reference in Darwin’s pamphlet collection catalogue reads “374 Turner W. Brain of Chimpanzee”. This turns out to refer to “Turner, William. 1866. ‘Notes more especially on the bridging convolutions in the brain of the chimpanzee.’ Proceedings of the Royal Society of London 5: 578-587”.

In the catalogue of Darwin’s papers were also thousands of items he had cut out of original publications, where perhaps only the name of the journal at the top of the page remained and very often not even that. However, today it is possible to search some of the best online text collections for the sentences in Darwin’s clippings to ascertain which publication they came from. For example, one item was catalogued as “Anon. 1861. The Field: 32 (part issue)”. I was able to expand this to “Harvey, R. 1861. Nest of the missel-thrush. The Field (13 July): 32”.

Surprising Finds

As there are literally thousands of works revealed in the new catalogue in Darwin Online, only a handful can be mentioned here. Previously, no works by the famous philosophers John Stuart Mill and Auguste Comte were known in Darwin’s library, now there are several. We now also know that Darwin owned a work by the great polymath Charles Babbage. Also found in the library is the memoir of William Chambers, the elder brother of Robert Chambers who is the secret author of the popular (pre-Darwin) evolution sensation, Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation (1844).

Other surprising discoveries include Paul Du Chaillu’s Explorations and Adventures in Equatorial Africa, an article titled “The Hateful or Colorado Grasshopper”, and other articles with alarming titles such as “The Anatomy of a Four-Legged Chicken” and “Epileptic Guinea-Pigs”.

Many of the works that had not been preserved with the part of the scientific library after Darwin’s death were more ephemeral matter such as catalogues, items of personal interest, on health, social issues, and the fringe ideas of enthusiasts who sent their publications to Darwin. These items are in some ways now more interesting to historians than more formal scientific publications. For example, there was the sumptuous 1872 coffee table book Sun Pictures: A Series of Twenty Heliotype Illustrations of Ancient and Modern Art (author unknown) which tells us that Darwin enjoyed art at home. In addition, there was also a mundane 1832 road atlas of England and Wales.

Darwin’s devotion to the “water cure” for his ill health is well known, but we did not have a record, until now, that Dr James Manby Gully’s book, The Water Cure in Chronic Disease: An Exposition of the Causes, Progress, and Terminations of Various Chronic Diseases of the Digestive Organs, Lungs, Nerves, Limbs, and Skin, and of Their Treatment by Water and Other Hygienic Means (1846), was on Darwin’s shelves. Unsurprisingly, for a man who took such assiduous care of his finances, Darwin had a book on this too – Robert A. Ward’s 1852 work, A Treatise on Investments.

We have found that many of the works that were not handed over to Cambridge in 1908 were among the oldest in the collection. This might have been why they were retained by the family and some later sold. These included Edmund Gibson’s Chronicon Saxonicum (1692); Johann Bauhin’s Historia Plantarvm Vniversalis (1651); Joseph Butler’s The Analogy of Religion, Natural and Revealed (1736); Maria Elizabeth Jackson’s Botanical Dialogues, Between Hortensia and Her Four Children (1797); and Thomas Burnet’s The Theory of the Earth (1684).

Digitising the Library

Darwin’s library was so vast that the reconstructed list is 300 pages long. But it is far more than a catalogue. The library has also been digitised: approximately 10,000 links to electronic copies of the works are provided.

This final phase of the project included digitising further works to add to Darwin Online and linking to the enormous volume we had already digitised over the years. Then, all of the references needed to be checked – three times – and links inserted to freely available online versions of the exact same edition that Darwin had. This was done about 10,000 times. Because Darwin’s library is now reunited with his complete publications, manuscripts and papers, it is possible to explore his work in unrestricted new ways.

The Voyage of Darwin Online

Once all the lists had been done, all the catalogues of rare books that can be found had been searched and the Correspondence scoured for all the references contained there, it was time to publish the list of Darwin’s complete library for the first time. No doubt there were items we have not found, and hopefully any we have missed will be sent for inclusion. But with such large projects, there comes a time when more weeks or months of searching produce too few results to warrant further delaying the release of the list to the public where it can be of use. At the time of writing, the library list on Darwin Online has already been visited over 15,000 times since 11 February 2024.

It is an immense relief and satisfaction to publish something that has been worked on for so long and which builds on the work of so many scholars. Along the way, so many discoveries sparked new opportunities for footnotes or cross references in Darwin Online, and many of the revelations would form the basis for research articles and news stories of their own. That is for the future.

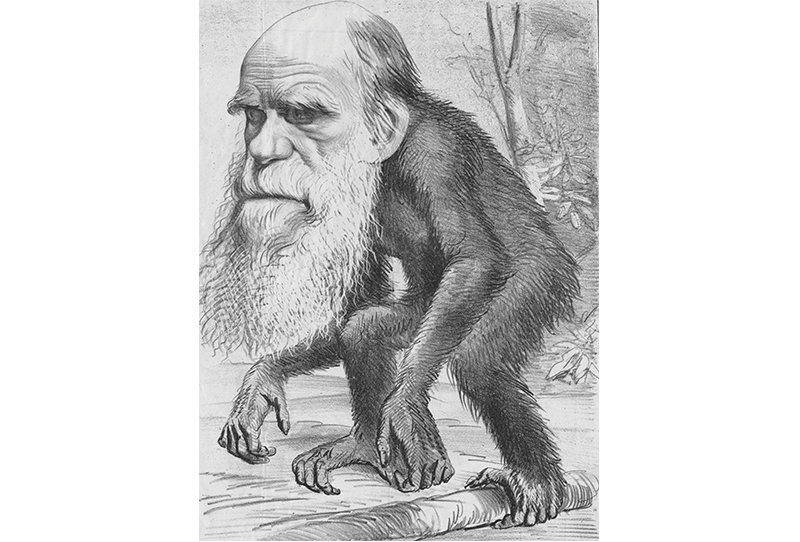

As for Darwin Online, our next major release will be caricatures of Darwin and his theories. In my book, Darwin: A Companion (2021), I published the most comprehensive catalogue of portraits of any scientist – over 1,000 unique Darwin portraits, including 210 oil paintings, watercolours and drawings, more than 600 printed portraits and caricatures, as well as over 240 three-dimensional works such as statues, busts and medallions and all known photographs, including a dozen previously unknown. And, unprecedentedly, it includes details of all known variants of these photographs produced to the early 20th century – more than 340. This is how Darwin’s appearance became so well known to the public during the 19th century and after. In February 2023 a revised version of the catalogue of photographs was published in Darwin Online, illustrated with 450 images.

The caricatures will be a similar release, with new discoveries and hundreds of images of caricatures and satirical images of Darwin’s theories from 1860 to 1939. Historians have come to recognise how important images of this kind are for the public understanding of science – or better put – public ideas about science since almost all of the images about Darwin’s theories are based on stereotypes, misconceptions (such as “Darwin said we come from monkeys”) and much older comic themes that just carried on being used. One of the main parts of this project is the contextual research necessary to explain what the images meant at the time to a modern viewer. That is the tricky part because, as trained historians know, without understanding the context, one cannot understand anything from history.

Dr John van Wyhe is a historian of science at the National University of Singapore, and the founder and director of Darwin Online . He has published 17 books, including Dispelling the Darkness: Voyage in the Malay Archipelago and the Discovery of Evolution by Wallace and Darwin (World Scientific Publishing, 2013).

Dr John van Wyhe is a historian of science at the National University of Singapore, and the founder and director of Darwin Online . He has published 17 books, including Dispelling the Darkness: Voyage in the Malay Archipelago and the Discovery of Evolution by Wallace and Darwin (World Scientific Publishing, 2013).