Singapore’s Pioneer Cartoonists

Many of the early cartoonists were ideologically motivated and their drawings aimed to bring about social and political change.

By CT Lim

Most children grow up reading cartoons and comics. While many people move on to other interests, you could say that I never “grew up”. The sense of wonder and excitement I felt whenever I flipped open a comic book bought with pocket money saved from skipping recess in school has never left me.

In the late 1980s, I started writing for BigO fanzine about music, comics and films. That led me to thinking seriously about popular culture, and how it reflected and shaped my worldview. When it came to selecting a topic for my history honours thesis at university, I wanted to do something about the political and visual culture in my own backyard – the history of political cartoons in Singapore. A few years later, I embarked on a part-time master’s degree on the history of Chinese cartoons in Singapore, and I ended up writing 40,000 words on the topic while working fulltime. I would go on to curate small shows about comics and cartoons, and eventually started writing comic books (or graphic novels) myself.

About a decade ago, I wrote two articles on comics and cartoons in Singapore for this publication. In 2012, I discussed the comics drawn by Eric Khoo (Unfortunate Lives) and Johnny Lau (Mr Kiasu), and how they reflected Singaporean society in the 1980s and 1990s.1 The second article, published a year later, was based on the exhibitions I helped curate in 2013 at the various public libraries and the National Library: the 24-Hour Comics Day Showcase and the Chinese cartoon exhibition held in conjunction with the 90th anniversary of the Lianhe Zaobao newspaper.2

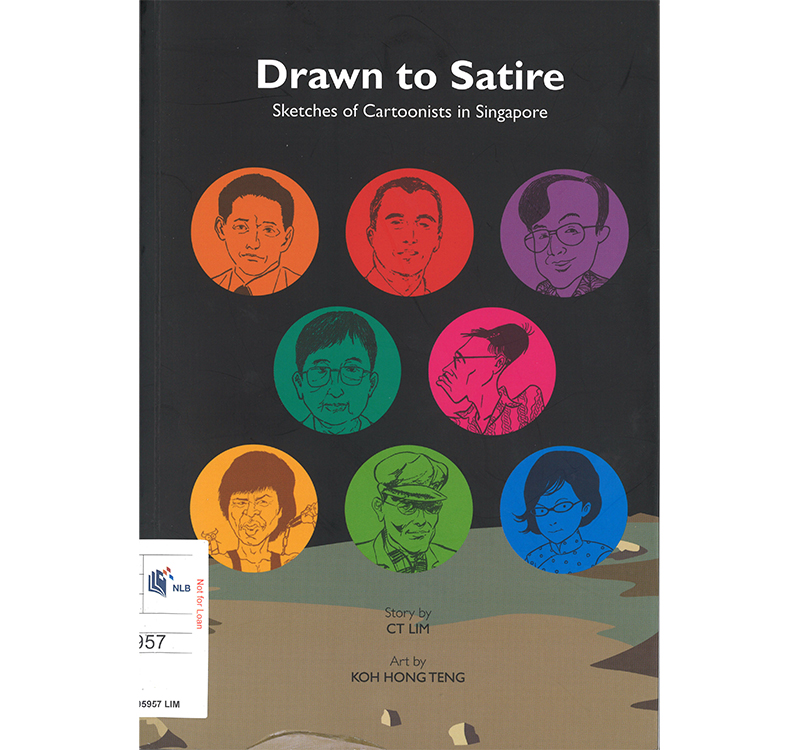

This current article, however, provides a snapshot of eight pioneer cartoonists in Singapore whom I showcased in a recent book. Published in 2023, Drawn to Satire: Sketches of Cartoonists in Singapore features illustrations by Koh Hong Teng.3 The eight cartoonists highlighted in the book are Morgan Chua, Dai Yin Lang, Koeh Sia Yong, Kwan Shan Mei, Lim Mu Hue, Liu Kang, Shamsuddin H. Akib and Tchang Ju Chi.

I decided to write the book because unlike in other countries, the history of cartoonists and comic artists is not well documented in Singapore. For example, in conjunction with the 2024 Paris Olympics, the Centre Pompidou held a major comics exhibition titled “Comics, 1964–2024” from 29 May to 4 November this year. The closest we have had to something like this was an exhibition on the history of Singapore comics that I co-curated with Sonny Liew in 2016 at the Central Public Library. The exhibition was part of Speech Bubble, a month-long event comprising programmes such as talks and workshops to celebrate Singapore comics.

While the exhibition had decent reviews and attendance, awareness of Singapore comics is still low among the public despite the popularity of foreign comics like Japanese manga. When Liew’s graphic novel, The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye, was published in 2015 (and subsequently won three Eisner Awards in 2017), many people asked me to introduce them to Charlie Chan even though the book is a fictional biography showcasing the life and work of fictional pioneering comic artist, Charlie Chan.4

Other than some of my own articles, there is no book on the history of cartoonists in Singapore. When the opportunity came for me and artist Koh Hong Teng to collaborate on a book, we decided to do one on the cartooning history of Singapore and its unknown links with the country’s art history. Some people may know of artists like Liu Kang, Lim Mu Hue and Koeh Sia Yong, but not many know that they also drew cartoons.

Of the eight cartoonists featured, I am personally familiar with four of them: Lim Mu Hue, Morgan Chua, Koeh Sia Yong and Sham. (I also met Liu Kang when I interviewed him.)

I first met Koeh when I interviewed him for my honours thesis in the mid-1990s, and I have enjoyed interacting with him over the years. In fact, I introduced him to Liew when the latter was researching his book, The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye. Maybe Charlie Chan was modelled after Koeh.

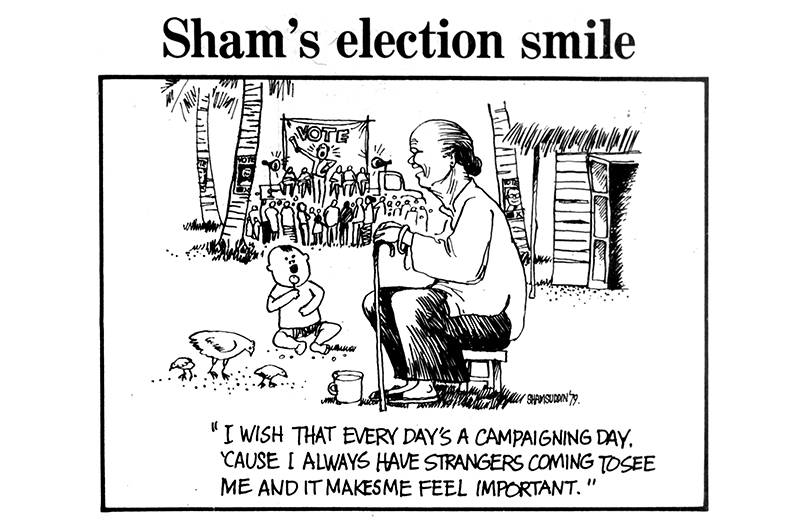

As for Shamsuddin, I discovered his 1970s cartoons in my archival search of old microfilms of the Straits Times for my honours thesis. Later on, I got to know his daughter, Dahlia Shamsuddin, a librarian with the National Library Board and fellow member of the Singapore Heritage Society. She said her father was very proud that his cartoons were analysed so thoroughly in an academic article as he was just drawing the cartoons and did not think much about the meanings behind them.5 I finally met Sham a few years ago, and he was a charmer.

I got to know Chua in 1999 when I did a small exhibition on political cartoons in Singapore featuring his works and those of Tan Huay Peng at the courtyard of the old National Library on Stamford Road. I gave a talk on that occasion and when Chua heard about it, he turned up. We went for coffee after that and became good friends, meeting many times over the years at the coffeeshop near the bus stop in front of the library. His standard order was chicken rice and kopi-o kosong (black coffee without sugar).

Another artist I had the honour to meet was Lim Mu Hue. From 2006, we would meet at the National Library at its new location on Victoria Street. We often dined at the cafe in the plaza outside the library as we were preparing for “Imprints of the Past: Remembering the 1966 Woodcut Show” held at the library.6 Lim was quite a character and I enjoyed talking to him and visiting him at his home. When I showed the story about Lim to his daughter Sharon, she was tickled that we managed to capture his eccentric spirit.7

For the stories of both cartoonists (and others in the book), we adopted an approach of creative non-fiction. Most artists (and, indeed, most of us) lead similar lives – we are born, grow up, go to school, get married, have kids, grow old and die. My challenge was to find an entry point into their world, a particular incident that we can amplify to capture their spirit, their raison d’etre. We took some liberties; some things in the book might have happened, some might not have. But our aim was to tell a good story and hopefully get readers to circle back to the original cartoons and stories.

Cartooning in Singapore

Singapore’s early newspapers were the first to include cartoons. The Straits Times, for example, featured entertainment news, local gossip and news from the metropolitan centre, as well as cartoons reprinted from London periodicals. In addition to newspapers, there were also interesting experiments like Straits Produce, a satirical magazine that was first published in 1868. Modelled after Britain’s leading humour magazine Punch, Straits Produce carried cartoons, caricatures, short stories, poems and humorous essays.8

Vernacular newspapers began rolling off the presses in the second half of the 19th century in Singapore, but the first local Chinese and Malay cartoons only appeared in the early 20th century. (We could not find any cartoons in Tamil newspapers during this period.)

Back then, the Chinese newspapers were mainly concerned about events in China such as the anti-Qing movement, the activities of Sun Yat Sen, the 1911 Revolution, the 21 Demands on China, the May 4th Movement, the Shanghai White Terror Massacre and the Japanese incursions into China. The Chinese community in Singapore was more interested in what was happening in China than in Singapore. As such, the cartoons published in the Chinese press during this period tended to focus on events in China and were very political.

The cartoons that appeared in Malay newspapers were more social in nature and outlook. The Malay press saw its role as educating the masses, rallying the intelligentsia and being a catalyst for social change. Cartoons were part of the arsenal for raising the consciousness of the Malays, but one which was leavened with humour.

Cartoon Pioneers

In this day and age, we have to be careful with the words we use. Terms like “pioneer” are loaded and can be contentious, just like terms like “Nanyang artists” and “founding fathers” (some people might ask, You mean there are no founding mothers?). In this case, we are using the term “pioneer cartoonists” loosely to refer to someone who was drawing cartoons from the early 20th century up to the postwar and independence years.

We are not saying that the eight people featured here are the very first cartoonists in Singapore or that they pioneered some kind of new cartooning technique. But they were among the early few to venture into this field or vocation, and they led interesting lives. Like all lists, it is subjective and there are others we may have inadvertently left out (or some would say neglected). We welcome all feedback and we are open to being corrected.

Tchang Ju Chi (1904–42)

Tchang Ju Chi was a pioneer artist in prewar Singapore. He was born in Chao’an, Guangdong province, and settled in Singapore in 1927 where he taught art in Yeung Cheng and Tuan Mong schools. As an editor of Xing Huang, the weekly pictorial supplement of Sin Chew Jit Poh, he drew many cartoons for the newspaper. He also used cartoons in his advertising work.

Tchang drew many cartoons about local life in early 1930s Singapore. This was significant because other writers and artists who arrived in Singapore from China still focused on China in their literary and artistic works , whereas Tchang focused on the sights and flavours of the Nanyang. However, this changed when the 1937 Sino-Japanese War broke out, and the cartoons by Tchang and Dai Yin Lang became more about the war situation in China. Tchang was killed in 1942 during the Sook Ching operation in Singapore.

Dai Yin Lang (1907–85)

Born in Kuala Lumpur, Dai Yin Lang was educated in China and graduated from the Faculty of Western Art at the Shanghai Academy of Art. An activist and a communist, Dai was influential in the development of cartooning in Singapore, drawing not only cartoons but also writing many articles before World War II about the form and function of cartoons. He was deported to China by the British in 1939 for his anti-colonial views. Like many others, he suffered at the hands of the Red Guards during the Cultural Revolution.

Like Tchang, Dai drew about the lived experiences of the people in 1930s Singapore. Typical of the cartoons of the day, both men’s cartoons had very few words as the literacy level was low in Singapore then. This is in contrast to the cartoons we see in the newspapers today which depend on captions, dialogue and wordplay. This meant the cartooning skills of Dai and Tchang had to be precise, without the use of words: 一针见血 (“to hit the nail on the head”). This is no easy task – then and even now.

Liu Kang (1911–2004)

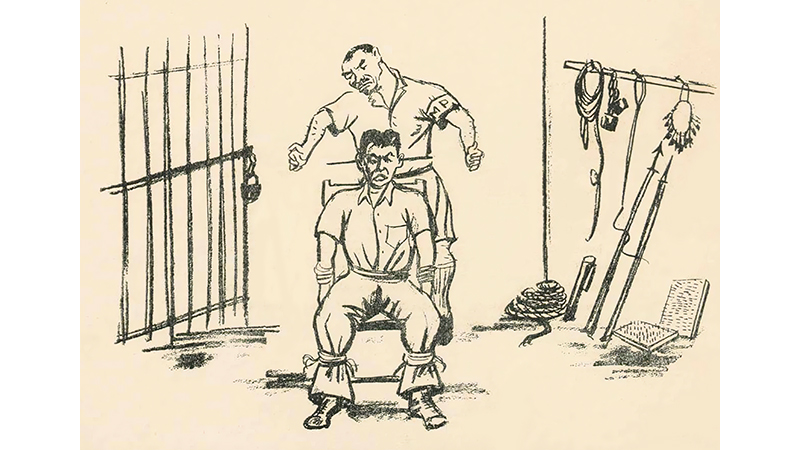

Liu Kang was one of the pioneers of art in Singapore. While well known as a painter, he also produced Chop Suey (1946), a series of comic books illustrating the atrocities committed by the Japanese against the people of Singapore during the Occupation years.9 Although Liu never drew cartoons after that, Chop Suey remains an important work in the history of cartoons in Singapore.

Kwan Shan Mei (1922–2012)

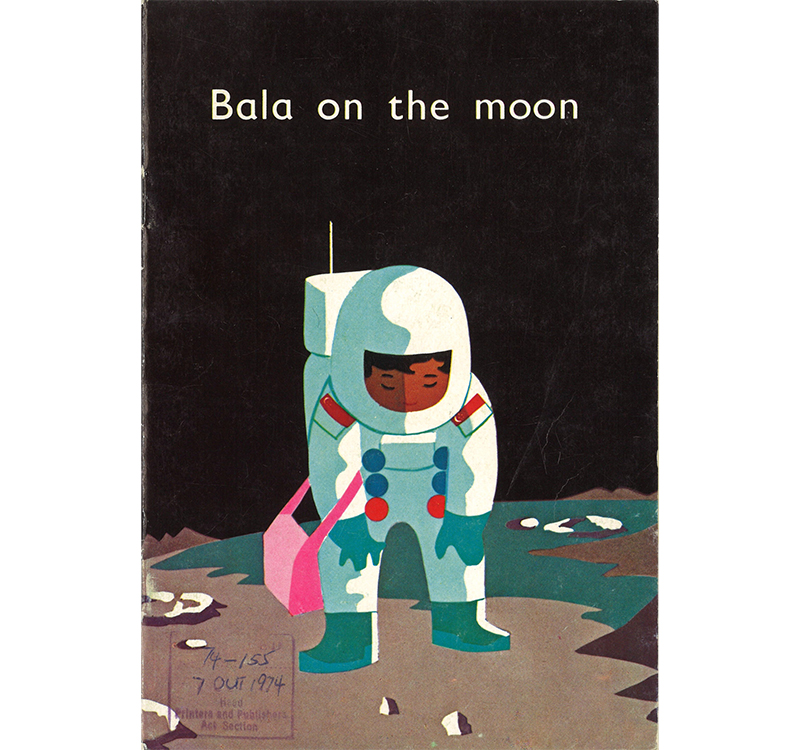

Born in Harbin, China, Kwan Shan Mei was one of the few female illustrators and cartoonists active in Singapore from the 1960s to 1980s. Her real name was Wong Fang Yan but she used Kwan Shan Mei as her pen name. She worked in Hong Kong in the 1950s before relocating to Singapore in the 1960s, drawing many of the textbooks of our childhood, such as the 24 readers published by the Ministry of Education as part of the Primary Pilot Project. Kwan taught at the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts (NAFA) in Singapore in the 1990s before moving to Vancouver, Canada, in 1999.

Like Sham, Kwan’s style is gentler and “prettier” in terms of aesthetics, which was suited for the nation-building era of the late 1960s and 1970s when applied arts like graphic design and illustration were important in helping to develop the economy of Singapore. Her non-confrontational style ensured her a steady stream of jobs from the Educational Publications Bureau (established by the Ministry of Education in 1967 to produce affordable textbooks) in the 1970s and 1980s.

Shamsuddin H. Akib (1933–2024)

Shamsuddin H. Akib may not be part of the golden age of Malay comics in the 1950s, but his contributions in the fields of advertising, illustrations and cartooning are memorable. Like Tchang Ju Chi and Koeh Sia Yong, he straddled the worlds of graphic design, commercials and cartoons.

In 1962, while working as a commercial artist at Papineau Advertising, Sham submitted a mural titled “Cultural Dances of Malaysia” for a competition in which five winning designs would be selected for the new passenger terminal building at Paya Lebar Airport. Sham’s mural was one of the chosen designs and it was installed on the ground floor of the airport above a row of phone booths. The mural is no longer intact today.10

Like Koeh, Sham drew cartoons for newspapers in the 1970s, focusing on local events (sports, elections). Instead of caricaturing politicians, Sham’s cartoons took a light-hearted look at policies and everyday living.

Lim Mu Hue (1936–2008)

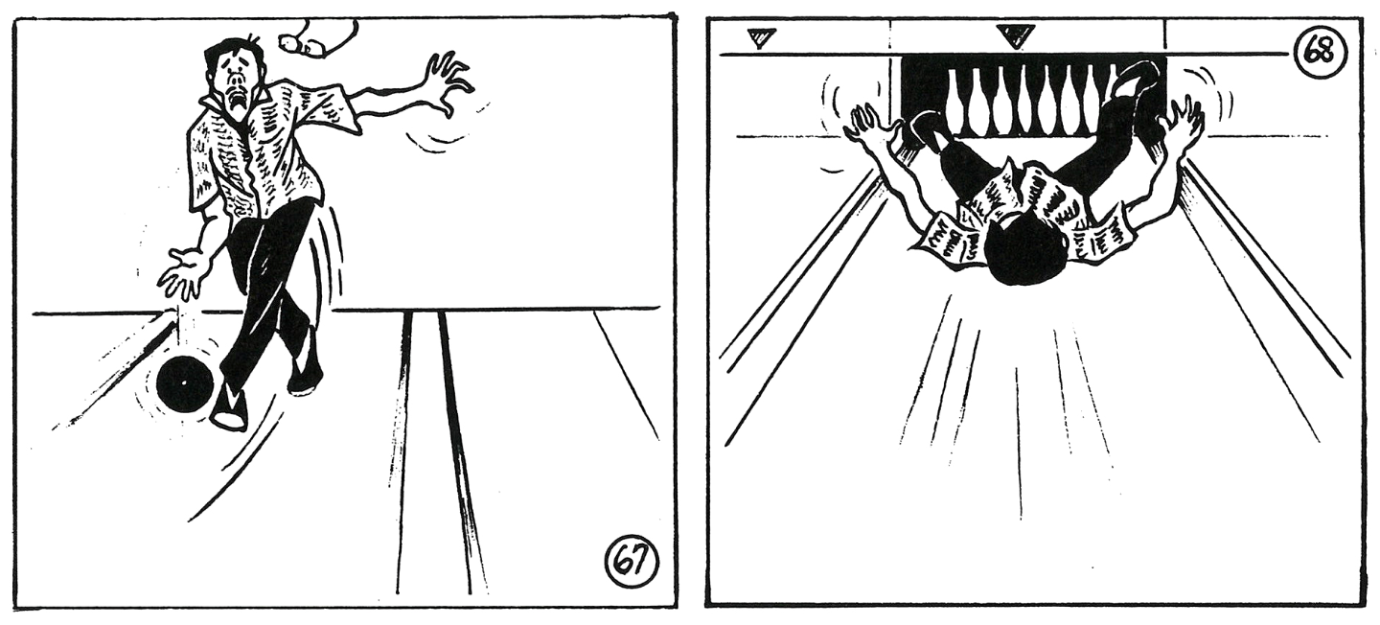

Lim Mu Hue has been described as the eccentric artist of the Singapore art scene in the 1970s. He once published a blank book titled 无字天书 (“Wordless Book”). But beneath the gruff exterior of a stubborn old man who loved his drinks and cigarettes lay a critical mind and generous spirit.

Lim can be considered a pioneer of conceptual art in Singapore. For one of his exhibitions in the 1970s, he took down all the works on the last day and visitors entered an empty gallery. But he was there to sign on the shirts of guests, and they became part of the artwork.

Lim’s innovative approaches extended to the cartoons he drew in the 1970s: his protagonist (who is the artist himself) breaks the fourth wall constantly and makes fun of himself. He makes us laugh at his own expense, so we can learn, understand and empathise.

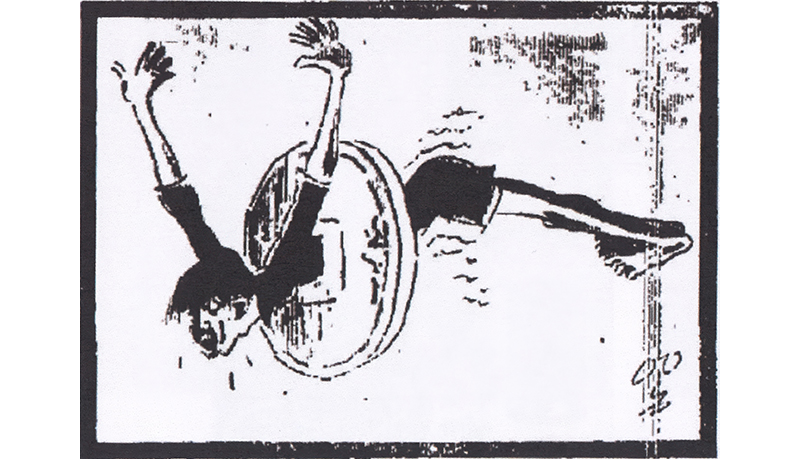

这下包中 (1958) by Lim Mu Hue. Images reproduced from Lin Mu Hua, 林木化正华画集 (新加坡: 林木化, 1990). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RDTSH 759.95957 LMH).

这下包中 (1958) by Lim Mu Hue. Images reproduced from Lin Mu Hua, 林木化正华画集 (新加坡: 林木化, 1990). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RDTSH 759.95957 LMH).Koeh Sia Yong (b. 1938)

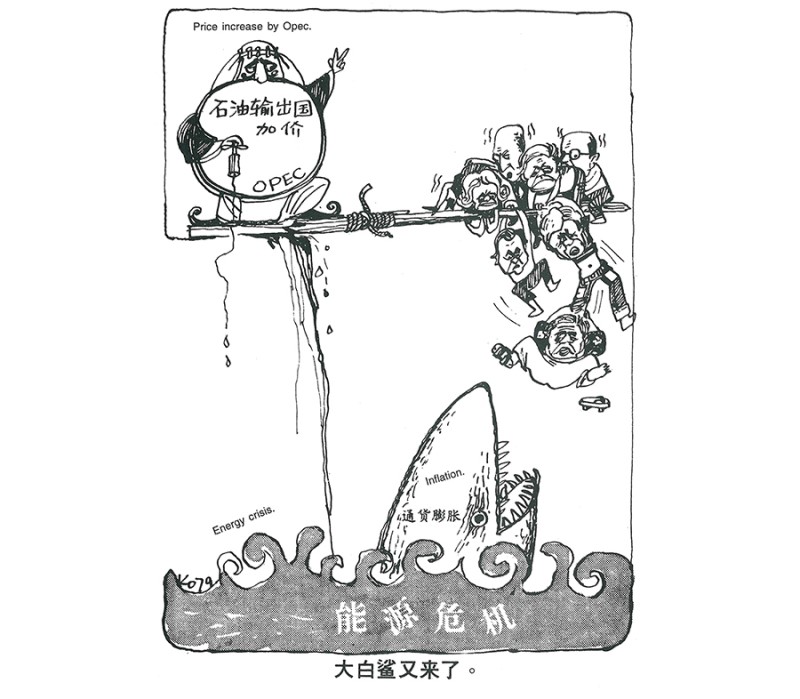

Koeh Sia Yong can be considered a second-generation artist in Singapore, but such labels are not useful as an individual is much more than the sum of the categories that museums, galleries, curators and critics choose to use on artists. Koeh is also a cartoonist, a woodcut artist and a believer of socialism in his younger days (and maybe now). He continues to draw cartoons today using his iPad.

Unlike his social realist works (woodcuts, paintings) in the 1950s and 1960s when he was a member and later the last president of the Equator Art Society, Koeh’s cartoons for Chinese newspapers in the 1970s focused on foreign politics rather than local events. This illustrates the difficulty of drawing political cartoons in that decade when maintaining national consensus in the mass media was required of writers and artists.

A cartoon about increasing oil prices by Koeh Sia Yong, 1979– 80. Image reproduced from Koh Sia Yong, A Mirror of Our Times 1979–19 80: A Story in Cartoon (Singapore: K.S. Yong, 1995). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 741.595957 KOH).

A cartoon about increasing oil prices by Koeh Sia Yong, 1979– 80. Image reproduced from Koh Sia Yong, A Mirror of Our Times 1979–19 80: A Story in Cartoon (Singapore: K.S. Yong, 1995). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 741.595957 KOH).Morgan Chua (1949–2018)

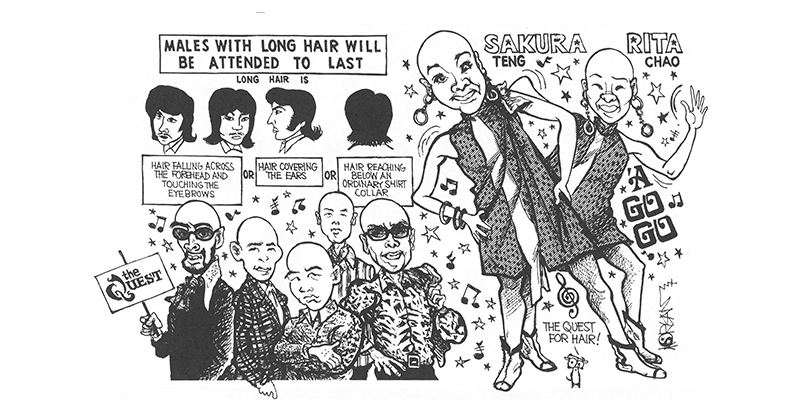

Morgan Chua was a Singaporean political cartoonist par excellence. A successor to the sharp penmanship of an earlier cartooning pioneer, Tan Huay Peng, Chua made his name at the Singapore Herald in the early 1970s before moving to Hong Kong to eventually take up the role of chief artist at the Far Eastern Economic Review. He returned to Singapore in the late 1990s and spent his last days here.

Chua was, and probably still is, the best political caricaturist we’ve had. His caricatures of world leaders graced many a cover of the Far Eastern Economic Review, capturing the attention of readers in a busy newsstand and boosting sales. From Hong Kong, Chua drew cartoons about Singapore leaders from time to time. It is unfortunate that with his departure from Singapore in the 1970s, the tradition of political caricaturing was severed in Singapore, so much so that in the 1990s, the Straits Times had to employ cartoonists from the Philippines.11 While we have political cartoons and comics today (especially on social media), we have never recovered the art of caricature drawing among our local cartoonists.

Common Threads

When we look at these artists, we can see that they share some commonalities. The cartoons of Tchang Ju Chi, Dai Yin Lang and Liu Kang focused on the Sino-Japanese War in China and the Japanese Occupation of Singapore. These pioneers drew their cartoons before or immediately after World War II.

Lim Mu Hue, Koeh Sia Yong and Kwan Shan Mei were either students and/or teachers at NAFA. In the case of Kwan, she taught Koh Hong Teng, the artist of Drawn to Satire, in the early 1990s. Since its inception, NAFA has produced many cartoonists, including Koh and Sean Lam, a Singaporean artist known for his two-part graphic novel adaptation of New York Times bestselling author Larry Niven’s sci-fi novel, Ringworld. Interestingly, the remaining two cartoonists, Shamsuddin H. Akib and Morgan Chua, had either studied at NAFA for a short while or had wanted to study there. Both Kwan and Chua worked in Hong Kong but at different times.

What other observations can we make from their life stories?

Cartooning was not a common profession back in the 1930s. That remains true today, although the situation is a little better now; currently art schools like NAFA even provide classes in cartooning. The eight cartoonists worked for newspapers, magazines and other periodicals.

Singapore did not have a dedicated cartoon magazine or comic books until the late 1970s and 1980s, though there were a few standalone issues now and then. This had to do with the state of Singapore’s economy in the postwar decades. When there was no spare pocket money for youths to spend, no publishers would publish comic books. As a result, cartoons only appeared in newspapers and magazines.

It was only when people became more affluent that comic books emerged, such as Roger Wong’s The Valiant Pluto-man of Singapore in 1983.12 None of the eight cartoonists worked under such favourable conditions though; they had to contend with the constraints and limitations of the newspaper and magazine format.13

We can also note that while contemporary cartoonists and comic artists aim to provide entertainment for young readers, the cartoonists of earlier generations could be classified as cultural workers. Cartoonists working for the press and magazines did not just draw cartoons; they were also journalists, artists and intellectuals.

Some of the pioneer cartoonists wanted to change the world, to bring about social and political change, and to make the world a better place. Some drew cartoons to fight against Japanese aggression in the 1930s, while others used their cartoons to promote anti-colonialism. Some like Tchang lost their lives because of their work. They were more idealistic than we are.

Given the Chinese majority in Singapore, it is not surprising that most of the early cartoonists were Chinese. As a result of prevailing social norms, few women became artists, much less be engaged in cartooning. Kwan was an exception, although she was an artist first in Hong Kong before moving to Singapore in the 1960s when she was already in her early 40s.

The 1950s can be termed as the golden age of Malay comics and cartoons, and there are many more Malay cartoonists that could have been featured.14 We only included one Malay cartoonist, Sham, in Drawn to Satire. Other researchers can and should continue what we have started. Today there are more women artists drawing comics and cartoons because of the popularity of manga and anime and the advent of art schools.15 We also have more Malay and Indian comic creators.

Finally, when all is said and done, being a cartoonist is still hard. It was true in the past and it is still true today. As I wrote in the final pages of Drawn to Satire: “Artists and their cartoons are products of their times. Seeing their works, we learn about their lives and struggles. Their many stories and experiences add graphic shades to the story of our past. Their collective stories embodied the history and heritage of cartooning in Singapore. It is not just one story but many different stories and experiences. Cartoonists are not winners. They are only human.”16

Cartoonists are drawn to satire. Long may they run.

CT Lim writes about history and popular culture. His articles have appeared in the Journal of Popular Culture and the International Journal of Comic Art. He is the co-author of The University Socialist Club and the Contest for Malaya: Tangled Strands of Modernity (Amsterdam University Press/NUS Press, 2012).

CT Lim writes about history and popular culture. His articles have appeared in the Journal of Popular Culture and the International Journal of Comic Art. He is the co-author of The University Socialist Club and the Contest for Malaya: Tangled Strands of Modernity (Amsterdam University Press/NUS Press, 2012).NOTES

-

Lim Cheng Tju, “Comic Books As Windows into a Singapore of the 1980s and 1990s,” BiblioAsia 7, no. 4 (March 2012): 22–26. ↩

-

Lim Cheng Tju, “Singapore Comics Showcase,” BiblioAsia 9, no. 3 (October–December 2013): 50–52. ↩

-

Lim Cheng Tju, Drawn to Satire: Sketches of Cartoonists in Singapore (Singapore: Pause Narratives, 2023). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 741.595957 LIM) ↩

-

Sonny Liew, The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye (Singapore: Epigram Books, 2020). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 741.595957 LIE); “Review: The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye,” Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia, 18 September 2015, https://kyotoreview.org/review-essays/art-of-charlie-chan-hock-chye/. ↩

-

Lim Cheng Tju, “Singapore Political Cartooning,” Southeast Asian Journal of Social Science 25, no. 1 (1997): 125–150. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Foo Kwee Horng, Koh Nguang How and Lim Cheng Tju, “A Brief History of Woodcuts in Singapore,” BiblioAsia 2, no. 3 (October 2006): 30–34. ↩

-

This is similar to the aim of my earlier comic book, Guidebook to Nanyang Diplomacy, a piece of speculative fiction about the Sepoy Mutiny of 1915 in Singapore. See Lim Cheng Tju, Guidebook to Nanyang Diplomacy (Singapore: COSH Studios, 2017). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 741.595957 LIM) ↩

-

Lim Cheng Tju, “The History of Comics and Cartoons in Singapore and Malaysia Part 2: The Early Comics/Cartoons,” SG Cartoon Resource Hub, 1 April 2022, https://sgcartoonhub.com/the-history-of-comics-and-cartoons-in-singapore-and-malaysia-part-2/. ↩

-

Timothy Pwee, “Cartoons of Terror,” BiblioAsia 11, no. 4 (January–March 2016): 102–105; Liu Kang, Chop Suey (Singapore: Printed at Ngai Seong Press, 1946). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.5106 CHO-LK]) ↩

-

Dahlia Shamsuddin, “The Forgotten Murals of Paya Lebar Airport,” BiblioAsia 17, no. 2 (July–September 2021): 4–9. ↩

-

Lim, “Singapore Political Cartooning.” ↩

-

Roger Wong, The Valiant Pluto-man of Singapore (Singapore: Fantasy Comics, 1983). (From PublicationSG) ↩

-

Lim, “Comic Books As Windows into a Singapore of the 1980s and 1990s.” ↩

-

Lim, “The History of Comics and Cartoons in Singapore and Malaysia Part 2”; Mazelan Anuar, “Kaboom! Early Malay Comic Books Make an Impact,” BiblioAsia 19, no. 4 (January–March 2024): 40–45. ↩

-

Lim Cheng Tju, “Stories by Female Comic Artists in Southeast Asia,” Academia, 2015, https://www.academia.edu/15829886/Stories_by_Female_Comic_Artists_in_Southeast_Asia. ↩

-

Lim, Drawn to Satire: Sketches of Cartoonists in Singapore, 140. ↩