Animals, Anxieties and Aspirations: The Earlier Years of the Singapore Zoo

The zoo was able to overcome major setbacks in its formative years to become the well-loved tourist attraction it is today.

By Choo Ruizhi

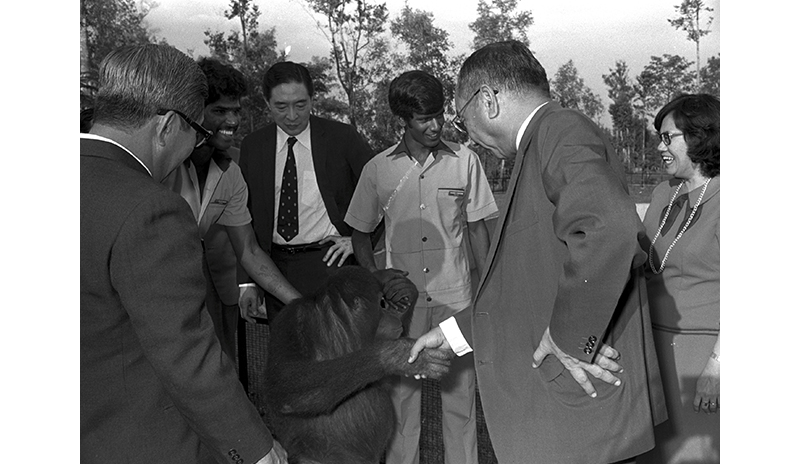

It was a little after 5 pm on 27 June 1973 when Deputy Prime Minister Goh Keng Swee was invited to shake hands with an orangutan.1 The primate was Susie, and the occasion was the official opening of the Singapore Zoological Gardens (known as the Singapore Zoo today). In his opening speech, Goh declared that the zoo was the latest “welcome addition to the amenities available to residents of Singapore”, a new recreational space for stressed, urbanised Singaporeans to relax. Spread over 28 hectares of land, the zoo featured about 270 animals from around 72 different species, many displayed in naturalistic enclosures.2

The idea of a zoo was conceived as early as 1967, just two years after Singapore’s independence. Amid significant sociopolitical and economic challenges, why did the leaders of this new nation dedicate significant financial, intellectual and material resources to the creation of a zoo when there were other more pressing matters of national development at hand? To better understand the origins of the Singapore Zoo, and why Goh found himself shaking hands with an orangutan on a Wednesday evening in 1973, we need to look back at Singapore’s early fascination for collecting, exhibiting and visiting exotic animal displays.

Singapore’s Early Zoos

The collection and display of exotic animals in Singapore may be traced to the 1850s, when prominent businessmen like Hoo Ah Kay (better known as Whampoa) maintained private menageries on their personal residences. Located off Serangoon Road, in present-day Bendemeer, Whampoa’s collection featured tapirs, giraffes and rhinoceroses.3

Public zoological gardens, however, would not be established in Singapore until 1875. Funded by the British colonial government, this zoo was located in the Botanic Gardens and exhibited animals that had been presented as gifts to state officials: from a leopard gifted by the Court of Siam to a female Sumatran rhinoceros from Andrew Clarke, Governor of the Straits Settlements. Unfortunately, the animals faced regular abuse and “malicious poisoning” by visitors.4

In 1881, citing financial constraints, the colonial government withdrew all financial support for the zoo, forcing it to rely on private contributions to fund the operating costs. Despite the best efforts of its staff, the zoo was finally closed in 1904.5 It would take almost 70 years before another publicly funded zoo materialised in Singapore – but in the meantime, privately operated zoos continued to attract visitors.

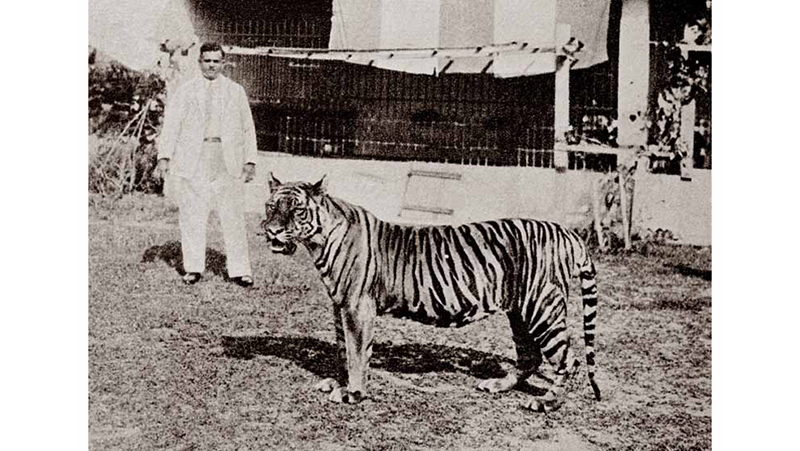

In 1928, the animal trader William Lawrence Soma Basapa established Punggol Zoo at 10 Mile Punggol Road. His collections featured Malayan tigers, Australian cassowaries and African lions. In early 1942, however, as the Japanese invasion of Singapore loomed, British authorities ordered the zoo’s dangerous animals killed and the harmless ones released into the wild.6

In postwar Singapore, private ventures showcasing wild animals remained highly popular with residents. In 1954, L.F. de Jong opened a zoo in Tampines that showcased cassowaries, tapirs, leopards, gibbons, crocodiles and snakes.7 Three years later, animal trader Tong Seng Mun set up the Singapore Miniature Zoo in Pasir Panjang.8 Just a year after that, the Shaw Brothers applied to run a zoo at the Great World amusement park, but the City Council rejected the proposal due to safety concerns for park visitors.9 In 1963, Chan Kim Suan, an exporter of rhesus monkeys, opened a private zoo near Punggol that featured tigers, kangaroos, tapirs and crocodiles.

Although many of these private zoos did not survive for long due to high financial expenses, their continued reappearance suggests that keeping, exhibiting and viewing exotic animals had become relatively commonplace activities in Singapore by this period, and that animal displays were spaces of persistent fascination for many residents.10

A Zoo in the City

In 1967, the Public Utilities Board (PUB) began to explore ways to better utilise the water bodies under its management for recreational purposes. Several thousand acres of land in the Seletar, Peirce and MacRitchie catchments were still closed off to the public. “One of the things considered was a zoo,” recalled PUB chairman Ong Swee Law.11

In late 1968, Ong assembled a steering committee of 12 PUB officials to drive the project. As the team comprised officials who were “without previous experience or knowledge of planning zoos”, they drew instead on the opinions and advice of experts and zoo directors from Europe, North America and Australia.12 In September 1969, the committee submitted a report to the government, recommending the establishment of a zoological gardens for the country. This was approved a month later, and Singapore Zoological Gardens, a $5 million public company, was formed to design, construct and manage the zoo, with Ong as chairman.13

After a visit to the Dehiwala Zoo in Ceylon (Sri Lanka today), Ong invited its director, Lyn de Alwis, to be the consultant-director of the Singapore Zoo on a one-year secondment. “They [Singapore authorities] knew what they wanted, having toured many zoos, particularly in the US and Europe. They saw what we had at Dehiwala and decided to give us the job,” de Alwis recalled.14

The committee had envisioned that it would feature an “open concept” architecture with animals displayed in naturalistic, spacious enclosures. To allay Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew’s concerns about having animals (and their waste) near a freshwater reservoir, stormwater drains would encircle the entire compound with a dedicated waste treatment plant to process zoological sewage.15

By 1971, development work on the 28-hectare zoo, including the construction of a metalled access road and sewage facilities, was underway.16 Some 2,000 trees were specially selected to replace “less desired” vegetation and to provide better shade and attract birds.17 Construction took 18 months and cost the government about $9 million. But despite efforts to create a modern, “wonder world of animals set amid the sparkling reservoir waters”, gaps remained – in some cases literally.18 Three months before the new zoo was slated to open, a series of dramatic animal escapes made headline news.

Animal Escapees

It started with the sun bears. On 5 March 1973, two “tame and less than half grown” bears squeezed their way out of a narrow gap in their cages. One was “re-captured immediately”, while the other eluded capture until it was shot dead two days later in the surrounding forested area, about 45 m from its enclosure.19

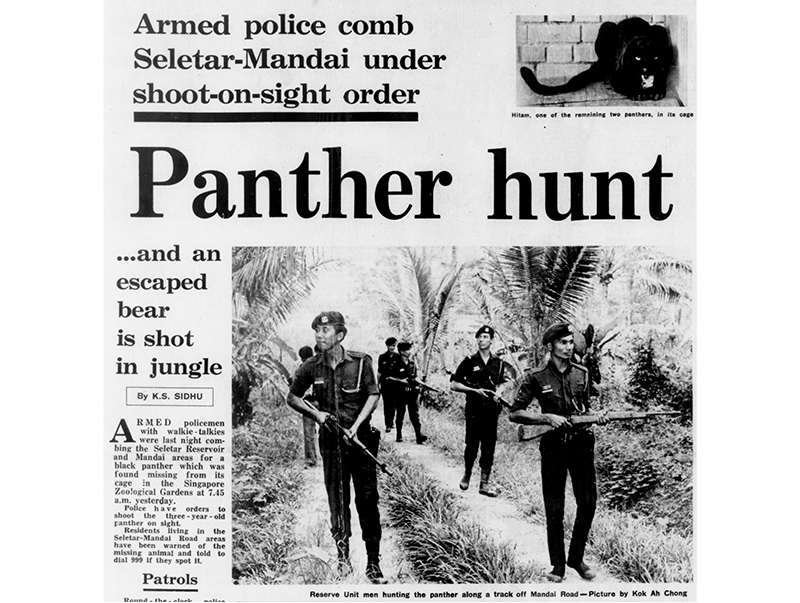

The next day, a three-year-old panther, the “youngest and smallest” of the zoo’s five panthers, slipped out of its cage, and escaped into the surrounding jungle. Zookeepers had named the panther “Twiggy” after the supermodel of the same name, as “it was slim and had thin legs”. The young feline had been locked in one of the “standard cages” in a quarantine area. The restless, frightened animal managed to escape by squeezing through the bars, which were each “about five inches apart”.20

Twiggy’s escape triggered a massive search effort. In addition to policemen, zoo staff and experienced hunters, three Reserve Unit troops totalling about 150 men were sent into the rainforests of Mandai, Seletar and Sembawang with a “shoot-to-kill” order. These personnel continued the search even amid heavy rain and darkness.21 Although armed patrols failed to locate the panther, a search party “spotted movement” in the thick vegetation surrounding the zoo shortly before noon on 7 March and shot dead the remaining fugitive sun bear.22

Reports of the runaway panther provoked widespread fear and excitement among Singaporeans. “We are worried about the children and are taking all precautions,” said Tan Thow Lar, a farmer. Nightlife in the nearby Sembawang Hills Estate slowed to a standstill as shops and households locked themselves in. Police warned students to keep away from the Seletar and Peirce reservoirs, while nearby schools shortened their teaching hours.23

The hunt for Twiggy reached its finale nearly 11 months later, when a clerk with the Singapore Turf Club spotted a strange animal entering a monsoon drain in the area on 30 January 1974. Policemen, Reserve Unit troopers, firemen and zoo staff rushed to the scene, bringing with them “tranquiliser guns, traps and special cages”. Petrol was poured into the drain and set ablaze with flare guns. Despite efforts to smoke out the panther, the animal did not budge.24 Two days later, the authorities flooded the underground drain while policemen stood ready with submachine guns. Soon after, a feline carcass floated out of the drain.25

Many citizens responded with outrage and grief for the “panther that harmed no one”.26 Others expressed their disgust at the “callous” and “ghastly way” in which a “young, probably sickly panther” had to be killed and likely “suffered a very painful death”.27

Despite additional security precautions, the zoo would suffer a few more animal escapes in 1974. In the early hours of 14 January that year, just weeks before Twiggy’s untimely end, Congo the Nile hippopotamus broke out of his enclosure and plodded into the placid reaches of the Seletar Reservoir. The massive animal would remain in the water body for 47 days before zookeepers unexpectedly succeeded in coaxing him back into his enclosure in early March with a bunch of bananas.28

Other less dramatic escapees in this period included an eland (a type of antelope) and a tiger – both were lured back into their enclosures with relatively little fanfare.29

Tighter security measures such as higher fences, reinforced walls and deeper moats were implemented, and appeared to have largely worked.

A New Era

The zoo welcomed its first public visitors on 28 June 1973, a day after the official opening. Entrance fees were priced at $2 for adults and $1 for children. The newly minted attraction became highly popular with citizens and tourists, and by June that year, it had welcomed over 850,000 visitors, far exceeding initial expectations.30 De Alwis was proud of how the zoo had turned out. “It’s a damned fine zoo,” he told the Straits Times in July 1973.31

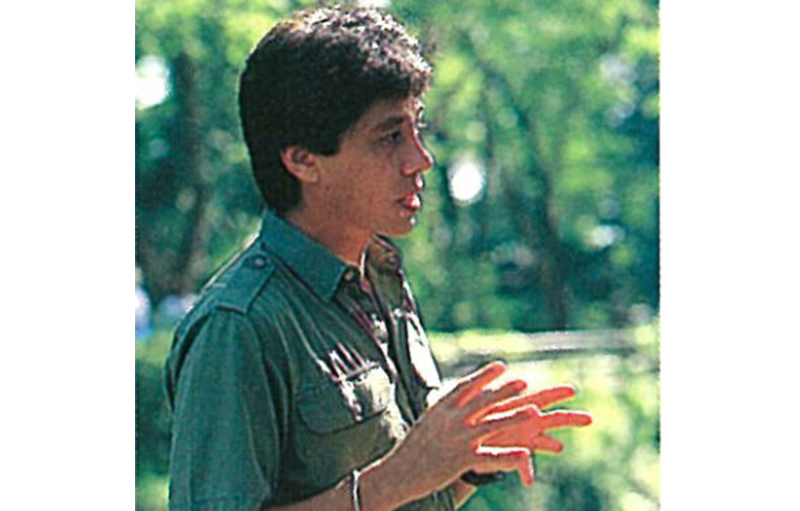

In subsequent decades, the zoo (and Singaporeans themselves) would witness significant transformations. In the 1980s, the zoo began marketing itself to attract more international companies and visitors to Singapore. Bernard Ming-Deh Harrison, formerly the zoo’s curator of zoology and assistant director, was appointed its executive director in 1981 at the age of 29. In 1982, the International Union of Directors of Zoological Gardens, “which only admits directors of zoos of international standards”, welcomed Harrison as its youngest member. Participating in such international organisations gave the Singapore Zoo access to wider global networks of expertise and animals, ushering in a new period of international animal exchanges.32

Thanks to collaborations with zoos in China and North America, Singaporeans were exposed to a wider diversity of exotic animals – from white tigers to golden monkeys – expanding the ways they could imagine and experience wild animals.33

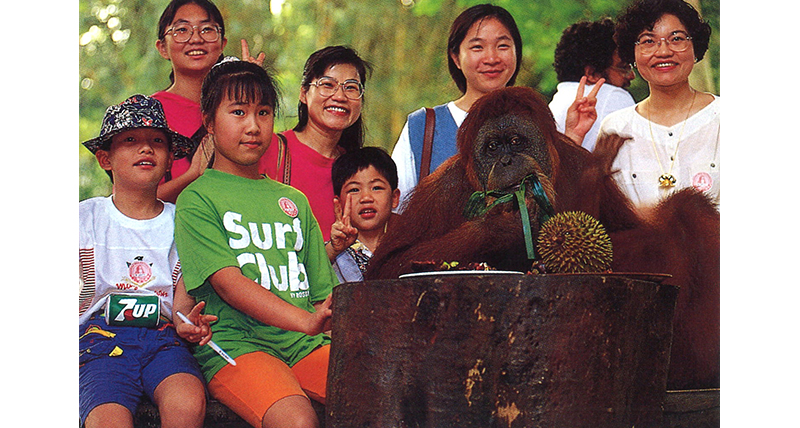

Under Harrison, the zoo pioneered “Breakfast with an Orangutan” in 1982, where paying visitors could dine with orangutans. The concept found great traction with tourists, facilitating the meteoric rise of Ah Meng, a female orangutan that many people would come to develop a deep affection for. The zoo had initially trained Susie (the orangutan Goh Keng Swee had shaken hands with) to be a zoo mascot, but she had died of pregnancy toxemia in 1974. (The zoo no longer has a programme forcing orangutans or other animals to dine with people.)

Ah Meng was chosen as a replacement because she was photogenic, “well-groomed” and comfortable with humans, having been raised as a household pet before being given to the zoo. Docile and personable, Ah Meng was photographed with many visiting celebrities and foreign dignitaries, and grew to become a household name among Singaporeans. According to Harrison, Singapore’s third president Devan Nair supposedly once remarked that “After Lee Kuan Yew, [Ah Meng is] the most well-known Singaporean in the world”.34 In 1992, Ah Meng became the first only non-human recipient of the Special Tourism Ambassador award by the then Singapore Tourist Promotion Board.35

The internationalisation of the Singapore Zoo continued into the 1990s and 2000s. On 26 December 1990, the zoo welcomed the birth of Inuka, the world’s first (and perhaps only) polar bear to be born in the tropics. Like Ah Meng, Inuka endeared himself to Singaporeans and international visitors alike, becoming a mascot for the zoo’s marketing efforts. But as a creature poorly adapted to the tropics, the polar bear also provoked many difficult conversations about animal welfare and zoological exhibits in Singapore. Such debates were led by the Animal Concerns Research and Education Society (ACRES), a local animal welfare group.36 (The zoo later said in 2006 that it would not bring any more polar bears to Singapore.37)

New Attractions

The 1990s also witnessed the launch of the world’s first Night Safari, which officially opened on 26 May 1994. Described as the first of its kind in the world, it allowed (and continues to allow) visitors to observe animals in nocturnal naturalistic settings, with even some free-ranging herbivores in certain parts of the park. At 40 hectares, it was nearly twice as large as the Singapore Zoo when it opened, and featured a collection of 1,200 animals from 100 different species, and “animals never before seen in Singapore”, such as a one-horned rhinoceros from India.

“Few people realise that 90 per cent of tropical animals are in fact nocturnal,” Ong Swee Law, by then executive chairman of the Singapore Zoo, wrote in a statement. “Night Safari gives visitors the opportunity to study this twilight world in complete safety and comfort.”38 There have been no animal escapes since its opening, reflecting the growing confidence in designing and operating “open zoo” enclosures.

The sheer novelty of the night zoo made it wildly popular with both local and international visitors. Open from 7.30 pm to midnight, the park added another highlight to Singapore’s burgeoning nightlife.39 Just a month after its opening, “overwhelming response” forced the Night Safari to suspend advance ticket sales and appeal to visitors to avoid coming on Saturday nights.40 An initial forecast of 180,000 visitors was exceeded fourfold, with 760,000 visitors flocking to its gates in the first year alone.41

In 2000, the Singapore Zoo – along with the Jurong Bird Park (renamed Bird Paradise when it moved to Mandai in 2023) and Night Safari – came under the management of Wildlife Reserves Singapore (renamed Mandai Wildlife Group in 2021), marking a gradual shift of priorities towards maximising the company’s financial sustainability.42

The restructuring led to the departure of key staff like Bernard Harrison in 2002, who had been with the zoo since its inception. Physically, the zoo underwent significant renovations. In March 2006, for instance, the zoo opened a $3.6-million Wildlife Healthcare and Research Centre where visitors can view surgery being carried out on animals through a live feed. Two months later, a free-ranging orangutan facility – the first in the world – was created using tall trees, thick branches, foliage and vines to replicate the primates’ natural environment.43

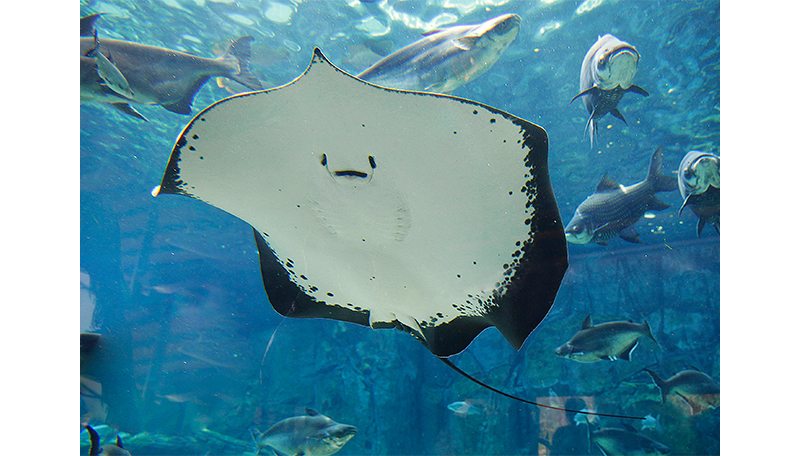

On 28 February 2014, the 12-hectare River Safari (now River Wonders) officially opened. It was Asia’s first and only river-themed wildlife park. Built at a cost of $160 million, River Safari also housed the world’s largest freshwater aquarium, and was home to 6,000 animals from 200 species. Inspired by the seasonally flooded forests of the Amazon River, the riverine park sought to showcase animals from many of the world’s rivers, and to promote a greater appreciation for freshwater habitat conservation among visitors.44

The park featured animals from diverse riverine habitats like the Amazon, Yangtze, Ganges, Nile and Mekong rivers. In addition to charismatic mammals such as Brazilian tapirs, South American jaguars and manatees, its freshwater exhibits also showcased exotic fishes like the Mekong giant catfish, the electric eel and the giant freshwater stingray. Attesting to the consistent and growing popularity of these animals, the River Safari hosted over a million visitors in its opening year, exceeding the number of guests the zoo and Night Safari had welcomed in their inaugural years.45

Attracting the most attention and excitement from visitors, however, were the River Safari’s giant pandas from China. On an initial 10-year loan from China, giant pandas Kai Kai and Jia Jia were specially flown in from Chengdu, China, and then transported by an air-conditioned truck to the Singapore Zoo when they first arrived in 2012.46 Notoriously difficult to breed, the pair formed the focus of numerous unsuccessful breeding efforts in subsequent years. These endeavours finally paid off when Jia Jia conceived via artificial insemination and gave birth to a male baby panda named Le Le on 14 August 2021, who became an instant hit with visitors.47

In 2022, the 10-year loan for Jia Jia and Kai Kai was extended for another five years until 2027, under an agreement signed by the China Wildlife Conservation Association and Mandai Wildlife Group. After Le Le turned two in August 2023, he was returned to China’s panda conservation programme in December that year.48

Grief and Remembrance

The early 2000s would also be a time of loss for the zoo though. On 8 February 2008, Ah Meng the orangutan died at the age of 48. News of her death elicited widespread expressions of grief from many Singaporeans. Her memorial service at the zoo, the first time such an honour had been accorded to any animal in Singapore, was attended by over 4,000 well-wishers.49

A similar outpouring of public sorrow was again seen when 27-year-old Inuka was put down on 25 April 2018 due to his deteriorating health. Hundreds of visitors attended the bear’s memorial service, and many Singaporeans shared their feelings online in the form of photographs, blogposts, Facebook posts and visual art.50 His death attracted reactions even from Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong. “Born and raised here,” Lee wrote on his Facebook, “he was as Singaporean as any of us.”51

A Space of Many Possibilities

While it is easy to tell the story of the Singapore Zoo as one of institutional success and visionary leadership, it is also interesting and important to consider the ways ordinary Singaporeans have responded to this national institution and its animals. Although there have been other local animal attractions in Singapore at the time, like the Jurong Bird Park and the Van Kleef Aquarium, the scale of emotional excitement, affection and pride residents have displayed for the zoo and its animals is remarkable in the history of the nation-state.

Despite the fact that Ah Meng the orangutan and Inuka the polar bear were not native to Singapore, they had endeared themselves to many people in this young, unlikely nation of migrants. While the Singapore Zoo is often described as a popular tourist destination today, it is also worthwhile to remember the institution at its origins: as a space of many possibilities, where animals came to represent the aspirations and anxieties of a new nation.

Choo Ruizhi is a Graduate Degree Fellow with the East-West Center, Honolulu, and concurrently a PhD student at the Department of History, University of Hawaii at Manoa. He is interested in histories of science, technology and animals in Southeast Asia. His Ahkong and Ahma used to run a medicine shop in Pek Kio, Farrer Park.

Choo Ruizhi is a Graduate Degree Fellow with the East-West Center, Honolulu, and concurrently a PhD student at the Department of History, University of Hawaii at Manoa. He is interested in histories of science, technology and animals in Southeast Asia. His Ahkong and Ahma used to run a medicine shop in Pek Kio, Farrer Park.Notes

-

“Dr. Goh Keng Swee Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Defence to Officiate at Today’s Opening Ceremony,” Straits Times, 27 June 1973, 19; R. Chandran, “A Haven for Animal Lovers of S’pore,” Straits Times, 28 June 1973, 15. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Feeding Animals at Zoo Strictly Forbidden: Dr Ong,” Straits Times, 16 June 1973, 16. (From NewspaperSG); Ilsa Sharp, The First 21 Years: The Singapore Zoological Gardens Story (Singapore: Singapore Zoological Gardens, 1994), 29. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING q590.7445957 SHA-[LKY]) ↩

-

“‘Whampoa’ Was the First of Singapore’s Towkays,” Straits Times, 13 March 1954, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

H.N. Ridley, “The Menagerie at the Botanic Gardens,” Journal of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 46 (December 1906): 133–194. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Timothy P. Barnard, Nature’s Colony: Empire, Nation and Environment in the Singapore Botanic Gardens (Singapore: NUS Press, 2016), 110. (From NLB OverDrive) ↩

-

“S’pore Zoo Starts from Scratch,” Straits Times, 20 October 1946, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Melody Zaccheus, “We Bought a Zoo: Singapore’s Small Havens for Wild Animals,” Straits Times, 3 June 2014, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/we-bought-a-zoo-singapores-small-havens-for-wild-animals. ↩

-

“A New Colony Zoo,” Singapore Free Press, 11 January 1957, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Snarls in City Council Over Zoo Plan,” Straits Times, 20 March 1958, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Singapore Puts Up Its Elephant Tax,” Singapore Free Press, 15 June 1950, 5; Zaccheus, “We Bought a Zoo”; “A Forgotten Past – A Zoo at Punggol,” Remember Singapore, 19 March 2012, https://remembersingapore.org/2012/03/19/a-zoo-in-punggol/. ↩

-

“The Men Behind the Project,” Straits Times, 29 January 1973, 14. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Govt’s $5 Mil Firm to Set Up a Zoo,” Straits Times, 24 April 1971, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Manik de Silva, “Lyn de Alwis, Sri Lanka’s Mr Zoo,” 1 July 1996, Himal SouthAsian, https://www.himalmag.com/profile/lyn-de-alwis-sri-lankas-mr-zoo. ↩

-

“Keeping the Water Clean for $1.7M,” Straits Times, 29 January 1973, 14; “SM: Zoo Pollution Was Main Worry,” Straits Times, 20 June 1993, 3. (From NewspaperSG); Sharp, The First 21 Years, 32. ↩

-

P.M. Raman, “S’pore Zoological Gardens to Be Opened in Mid-June,” Straits Times, 30 April 1973, 24. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Chandran, “A Haven for Animal Lovers of S’pore.” ↩

-

K.S. Sidhu, “Panther Hunt,” Straits Times, 8 March 1973, 1; R. Chandran and K.S. Sidhu, “Panther: Zoo to Hold Inquiry,” Straits Times, 11 March 1973, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Mohan, “Panther Escape: Official Resigns”; Mohan, “The Missing Panther: Secret’s Out”; “A Postmortem on Twiggy the Panther.” ↩

-

Chandran and Sidhu, “Panther: Zoo to Hold Inquiry”; Bernard Doray, “Panther: Eight Hunters Join in Search,” Straits Times, 13 March 1973, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

K.S. Sidhu, “Panther Hunt,” Straits Times, 8 March 1973, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

K.S. Sidhu and Shen Swee Yong, “Escaped Panther: Workers Quizzed by Police,” Straits Times, 10 March 1973, 28. (From NewspaperSG); Sidhu, “Panther Hunt”; Chandran and Sidhu, “Panther: Zoo to Hold Inquiry.” ↩

-

N.G. Kutty, Gerald Pereira and Jacob Daniel, “All-night Vigil After Bid to Flush It Out Fails,” Straits Times, 31 January 1974, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Flares Killed Twiggy the Panther,” Straits Times, 5 February 1974, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

CMC, “Panther That Harmed No One,” Straits Times, 5 February 1974, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Unhappy Ending,” Straits Times, 3 February 1974, 8; Gerald de Cruz, “Problems of Keeping an Open Zoo,” New Nation, 12 February 1974, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Ming-Deh Harrison, oral history interview by Jason Lim, 2 October 2007, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 2 of 5, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 003217), 30–31; S.M. Muthu, “Search On for Hippo Missing From Zoo,” Straits Times, 15 January 1974, 1; “Hunt for Hippopotamus Stepped Up,” New Nation, 15 January 1974, 1; “Missing Hippo Seen Having a Dip,” Straits Times, 17 January 1974, 1; “When Congo Decided He Wasn’t Going to Be Pushed Around,” Straits Times, 7 March 1974, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Antelope Latest Zoo Escapee,” Straits Times, 31 January 1974, 1; N.G. Kutty, “Hunger Drives ‘Prodigal’ Eland Back to the Zoo,” Straits Times, 11 February 1974, 1; “Staying Open,” Straits Times, 7 February 1974, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Zoo Will Get Its Millionth Visitor in October,” New Nation, 28 June 1974, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

For comparison, zoo directors typically attain their posts at around the age of 50. Bernard Ming-Deh Harrison, oral history interview by Jason Lim, 6 March 2008, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 4 of 5, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 003217), 64–84; “Gift of White Rhinos Raises Zoo’s Hope,” Straits Times, 27 October 1981, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Sandra Davie, “Million-Dollar Monkeys,” Straits Times, 22 April 1987, 24; “Rare White Tigers to Go on Show at Zoo,” Straits Times, 15 April 1988, 16. (From NewspaperSG); Harrison, oral history interview, 6 March 2008, Reel/Disc 4 of 5, 64–84. ↩

-

Bernard Ming-Deh Harrison, oral history interview by Jason Lim, 6 March 2008, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 3 of 5, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 003217), 49–51. ↩

-

K.C. Vijayan, “Ah Meng Dies,” Straits Times, 9 February 2008, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/ah-meng-dies. ↩

-

Amy Corrigan and Louis Ng, “What’s a Polar Bear Doing in the Tropics?” Animal Concerns Research and Education Society, 2006, https://acres.org.sg/core/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Whats-A-Polar-Bear-Doing-in-the-Tropics-report.pdf. ↩

-

“Singapore Zoo’s Inuka the Polar Bear Put Down at 27 on ‘Humane and Welfare Grounds’,” Straits Times, 25 April 2018, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/singapore-zoos-inuka-the-polar-bear-put-down-at-27-on-humane-and-welfare-grounds. ↩

-

“$60m Night Zoo Opens,” Straits Times, 29 April 1994, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Rohaniah Saini, “‘Make Them Happy and They Will Breed’,” Straits Times, 29 April 1994, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Ginnie Teo, “Safari Stops Sale of Advance Tickets,” Straits Times, 22 June 1994, 22. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Bernard Harrison, Singapore Zoological Gardens Annual Report 1994/1995 (Singapore: Singapore Zoological Gardens, 1995), 11. (From National Library Online) ↩

-

Harrison, oral history interview, Reel/Disc 3 of 5, 42–63; Harrison, Singapore Zoological Gardens Annual Report 1994/1995, 10. ↩

-

Mak Mun Sun, “Woo… The Zoo Is Cool,” Straits Times, 20 May 2006, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Zoe Yeo Lock Yan and Fiona Lim, “River Safari,” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published 25 June 2015. ↩

-

Lucas Romero, “Number of Visitors to the River Wonders in Singapore from 2014 to 2022,” Statista, 2 April 2024, https://www.statista.com/statistics/1025414/singapore-river-safari-visitor-numbers/. ↩

-

“S’pore Welcomes Kai Kai and Jia Jia,” Straits Times, 17 September 2012. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Transcript of Speech by Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong at the River Safari Grand Opening, 28 Feb 2014,” Prime Minister’s Office, 28 February 2014, https://www.pmo.gov.sg/Newsroom/transcript-speech-prime-minister-lee-hsien-loong-river-safari-grand-opening-28-feb-2014; Natasha Ganesan, “Singapore’s First Giant Panda Cub Le Le to be Separated from Mum As He Turns Two,” CNA, 14 August 2023, https://www.channelnewsasia.com/singapore/panda-le-le-jia-jia-separated-independence-mandai-wildlife-group-3697221; Ng Kai Ling, “The Seed That Grew Into a Wildlife Park,” Straits Times, 3 February 2013, 14. (From NewspaperSG); Ng Keng Gene, “Singapore Gets First Panda Cub, Born to Kai Kai and Jia Jia at River Safari,” Straits Times, 15 August 2021, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/singapore-gets-first-panda-cub-born-to-kai-kai-and-jia-jia-at-river-safari. ↩

-

Koh Wan Ting, “Giant Pandas Jia Jia, Kai Kai to Extend Stay in Singapore Until 2027,” CNA, 2 September 2022; Mandai Wildlife Reserve Media Centre, https://www.channelnewsasia.com/singapore/giant-pandas-jia-jia-kai-kai-extend-singapore-stay-2916001; “Singapore’s Giant Panda Cub Le Le Will Move into China’s Panda Conservation Programme in December,” Mandai Wildlife Reserve, 22 September 2023, https://www.mandai.com/en/about-mandai/media-centre/Singapores-Giant-Panda-cub-Le-Le-will-move-into-Chinas-Panda-Conservation-Programme-in-December.html. ↩

-

Nur Dianah Suhaimi, “Memorial Service for a Singapore Icon,” Straits Times, 10 February 2008, 4; Maria Almenoar, “Goodbye, Ah Meng,” Straits Times, 11 February 2008, 4; Ho Lian-Yi, “Ah Meng Dies,” Straits Times, 9 February 2008, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Kimberly Chia, “Letting Go of Inuka,” Straits Times, 26 April 2018, A10. (From ProQuest via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Lee Hsien Loong, “It Was With a Heavy Heart That I Read About Inuka’s Passing Yesterday Morning,” 26 April 2018, Facebook, https://m.facebook.com/125845680811480/posts/1845996398796391/?_rdr. ↩