At Wat Ananda, Thai Buddhism with a Singaporean Twist

Despite the golden stupa and ornate roofs that indicate this is a Thai Buddhist temple, the Singaporean influences are not hard to spot at Wat Ananda Metyarama.

By Thammika Songkaeo

On a little hill, sandwiched between Block 140 Jalan Bukit Merah to the east and the cars speeding over the Bukit Merah Flyover to the west, is a little piece of Thailand. On top of the knoll lies Wat Ananda Metyarama, Singapore’s oldest Thai Buddhist temple. The temple’s Thai characteristics are unmistakable. If you are approaching the temple from the entrance facing Jalan Bukit Merah, you will need to walk up the stairs whose sides are adorned with Thai motifs. At the top of the slope, you can spy a tall golden stupa perched on the roof of the building.

After you’ve made the 37 steps up the hill to reach the ornate gateway of Wat Ananda, a small Buddhist shrine lies on your left. Go up further and you’ll arrive at the entrance of Julamee Prasat, which is described as a Theravada columbarium (Theravada Buddhism is one of three major schools of Buddhism, and the predominant school in Thailand1). This columbarium occupies the first floor of the building with the stupa on top. Go past the columbarium and you will be greeted by the main shrine: a large, single-storey building with gold trimmings on the roof in the distinctive Thai style.

Wat Ananda has been in Singapore for more than 100 years and that time here has left its mark. All around the temple’s compound are elements that would not normally be found in a Buddhist temple in Thailand. One obvious sign is the round, red Chinese lanterns that liberally adorn the ceilings in the compound.

Then there are the many statues of Guanyin, the Chinese Goddess of Mercy, that have been placed in positions of honour. A large white statue of Guanyin is the central figure in a low building to the right of the main shrine. Next to this building is a covered porch where a smaller, but still tall, golden figure of Guanyin resides, flanked by statues of two monks. Guanyin, however, is a more common feature of Mahayana Buddhism, the school of Buddhism commonly found in countries like China, Korea and Japan.

Wat Ananda may be known as a Thai temple but it definitely shows signs of being localised. Although older Thais still show up in traditional Thai costume on religious occasions, the temple has become a place for Singaporeans to get a dose of Theravada Buddhism and the Land of Smiles all at once. Even what the temple celebrates and how it celebrates those occasions have been adapted to local culture and customs, and Singaporeans’ cravings for blessings.

Loy Krathong

Take the festival of Loy Krathong, which is celebrated all over Thailand and usually falls in November. On the evening of the full moon in the 12th month of the Thai lunar calendar, a small krathong (meaning “basket” or “boat”) – constructed from a slice of the trunk of the banana plant and bearing flowers, incense sticks and a lit candle – is floated on a river to honour and thank the Goddess of Water. This festival is celebrated at Wat Ananda as well, though not in a way typically done in Thailand.

At the 2023 celebration of the festival on 26 November, Luang Phor Amnuay – “Luang Phor” means “Venerable Father” and is a title for senior monks – invited visitors to buy and float krathong costing $20 each in a large, mustard-coloured inflatable pool. Swirling around in the pool under clear blue skies, the krathong felt no tug of a natural stream. This was in sharp contrast to the krathong in Thailand that were floated that evening under darker skies, riding on currents towards the mouth of the Chao Phraya River.

On that day, Thais visited Wat Ananda to socialise and make some merit, while Singaporeans, mostly of Chinese descent, seemed more focused on attaining better fortune by praying in front of the inflatable pool. A carnival-like atmosphere hung over Wat Ananda, similar to the temples in provincial Thailand.

“Lai, lai, boy, lai,” urged Luang Phor Amnuay. “Come, float krathong. Come for good luck. You, also daddy and mummy for zuo gong.” (lai means “come” and zuo gong means “work” in Mandarin.) His rapid mishmash of Mandarin and Singlish phrases were targeted at the Singaporeans present, and not at the Thais who were at the temple that day. Noticeably, too, he did not incorporate Thai into Sanskrit chants, knowing perhaps that Thais did not see Loy Krathong as an occasion to connect with Buddhism. On that day, the Thais in attendance could be seen dancing to traditional Thai music and cheering on heavily made-up beauty pageant contestants in the parking lot. The Thais were mainly families who wanted to show their Singapore-raised children how Loy Krathong is celebrated, as well as dating couples who floated the krathong for happiness and everlasting love.

The unique way that Loy Krathong is celebrated in Wat Ananda encapsulates how the temple merges both its Thai and Singaporean influences to create a final product that is neither entirely Thai nor Singaporean.

The Early Years

The temple’s roots go back to the early decades of the 20th century. It was founded in 1918 by a monk, Venerable Luang Phor Hong Dhammaratano (Phra Dhammaratano Bandit).2 Originally from Bangkok, Dhammaratano had lived in Pulau Tikus in Penang, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), India and Burma (now Myanmar), and was a polyglot proficient in Sinhalese and Mandarin.3

The Thai consulate offered Dhammaratano land beside the Thai Embassy, along today’s Orchard Road, so that he could build a temple. But as Orchard Road was not easily accessible at the time, Dhammaratano declined as he felt that it was too far from the town centre. Instead, he decided to set it up on Silat Road in what is now the Bukit Merah area.4 Wat Ananda Metyarama was completed in 1923, largely with the financial support of the Chinese in Singapore.

Even in the early years, while it clearly had Thai influences, the temple also served other Theravada Buddhists, notably Buddhists among the Ceylonese community in Singapore. According to Anne M. Blackburn, who has written about Ceylonese Buddhism in colonial Singapore, “[i]t is likely that some among Singapore[’s] Ceylonese Buddhist population attended rituals at Wat Ananda during the 1920s”. She noted that “Wat Ananda was located close to the Spottiswoode Park and Outram Park area of Singapore, core residential areas for the city’s Ceylonese. Moreover, since Dhammaratano apparently knew Sinhala and was familiar with Ceylon’s Buddhist environment thanks to his travels, he would have been a reassuring figure to Singapore’s Ceylonese Buddhists”.5

However, due to the differences between Thai (then known as Siamese) and Sinhala Pali chanting styles, that would have “reduced somewhat the comfort offered by Dhammaratano’s ritual work”. As a result, the Ceylonese decided to worship at the Sakya Muni Buddha Gaya Temple instead, which had been established on Race Course Road in 1927. Chinese Buddhists, who were more likely to have been following the Mahayana style of Buddhism, began to worship at Wat Ananda,6 importing the Mahayana culture and growing the temple’s Sinification.

When Dhammaratano died in 1952, Venerable Phra Rajayankavee succeeded him as chief abbot and renovated the temple in 1953. After Venerable Chao Khun Phra Tepsiddhivides became chief abbot in 1974 (he is still the chief abbot today), he saw to the temple’s expansion. In 1979, a pagoda and a three-storey residential block for monks were constructed. The pagoda was officially declared open by Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn, the second daughter of King Bhumibol Adulyadej, on 27 June 1985.7 The temple continued with more additions and expansions over the years. In 1995, the temple erected the golden statue of Guanyin in a covered porch next to the main hall. More facilities were completed in 1997, such as the three-storey building now housing the temple’s office, library and columbarium.8

The most recent, and most noticeable, addition took place in 2014, when a five-storey extension – in the shape of a futuristic, cube-like structure was completed for the temple’s 90th anniversary. Instead of traditional Thai Buddhist style, “the temple wanted a different look to attract younger devotees,” said its architect, Carl Lim of Czarl Architects. The new building houses monks’ quarters, prayer halls, meditation centres, classrooms, a museum, and a dining hall.9

Even as the temple expanded physically, it continued to do outreach as well. In 1966, the temple established the Ananda Metyarama Buddhist Youth Circle as the first Buddhist youth circle in Singapore. In 2006, on its 40th anniversary, it was renamed Wat Ananda Youth. The majority of its activities are held in the temple. Since its inception, the youth group has organised events to help spread the tenets of Buddhism and to preserve the Thai Theravada tradition in Singapore.10

Links to Thailand

Wat Ananda is not Singapore’s only Thai temple, but it is possibly the most well-known one. It is the only temple outside of Thailand to be recognised by Thai royalty. In 2016, on the occasion of the 70th anniversary of King Bhumibol Adulyadej’s accession to the throne, celebrations were held at the temple on 9 June. Thongchai Chasawath, then Ambassador of Thailand to Singapore, accompanied by government officials, and family and staff of the Royal Thai Embassy, along with more than 100 Thais and foreigners in Singapore, meditated and prayed for the king at the temple.11 When the king died later the same year on 13 October, both Thais and Singaporeans turned up at the temple on 15 October to pray for the late king. The mood was sombre as the crowd of almost 100, mostly dressed in black, clasped their hands together and chanted prayers in front of the late king’s portrait.12

The temple’s monks themselves are also mostly from Thailand. Back in 1976, the former prime minister of Thailand, Thanom Kittikachorn, was even ordained as a Buddhist monk at the temple after being ousted from the country during the bloody student riots in 1973. He returned to the temple in February 1986 for the Nimitta Sima ceremony to lay nine 100-kilogram sacred stones to consecrate the part of the temple that can be used for the ordination of monks.13

Festivals and Celebrations

These Thai links do not erase the many Chinese influences one can see. The local Chinese community has been closely associated with the temple from the outset, evidenced by the large number of Chinese donor names on the walls. Due to the popularity of the temple with Chinese devotees, the temple celebrates non-Thai and also non-Buddhist festivals.

During the 2024 Lunar New Year period, for instance, monks conducted chanting sessions and after each session, wished temple-goers “新年快乐, 身体健康” (xinnian kuaile, shenti jiankang; “happy new year and good health” in Mandarin). The monks then invited those who wished to receive a hong bao (“red packet”) to approach them. According to Chio Khee Teng, president of Wat Ananda Youth, monks at the temple give red packets to children. This is not practised in temples in Thailand though.

Then, there is the celebration of Ullambana on the 15th day of the seventh month of the lunar calendar, known as the Hungry Ghost Festival in Singapore. It is called Zhong Yuan Jie (中元节) in Taoism and the Yu Lan Pen (盂兰盆) festival in Buddhism (Yu Lan Pen being a transliteration of the Sanskrit name Ullambana).14

As the festival has its origins in the Mahayana scripture about filial piety known as the Yulanpen Sutra or Ullambana Sutra, Ullambana is not commonly observed in Thailand, where Theravada Buddhism is the official religion. At Wat Ananda, however, Ullambana is a big celebration during which devotees make donations for the monks to conduct special chanting sessions. Food items placed on altars are also offered to ancestors, and bulletin boards are covered in yellow.15

During Ullambana in September 2023, Luang Phor Amnuay invited devotees to write the names of their ancestors on a slip of paper and to drop this into a bowl. “But Chinese I cannot read,” he nevertheless admitted, hinting perhaps that they should write the names in English so that he could include them in the chants.16 After the chanting, the monks individually accepted red packets from worshippers.

Wat Ananda celebrates Buddhist festivals such as Vesak Day – which commemorates the birth, enlightenment and attainment of Nirvana of Buddha – and the annual Kathina Festival which celebrates the end of Vassa, an intensive three-month-long retreat for monks, in the same way as temples in Thailand do. On these occasions, the temple is packed to the brim, and those who make it to the main hall may chance upon more signs of the temple’s “Singaporeanisation”, if they know where to look.

Main Shrine and Temple Murals

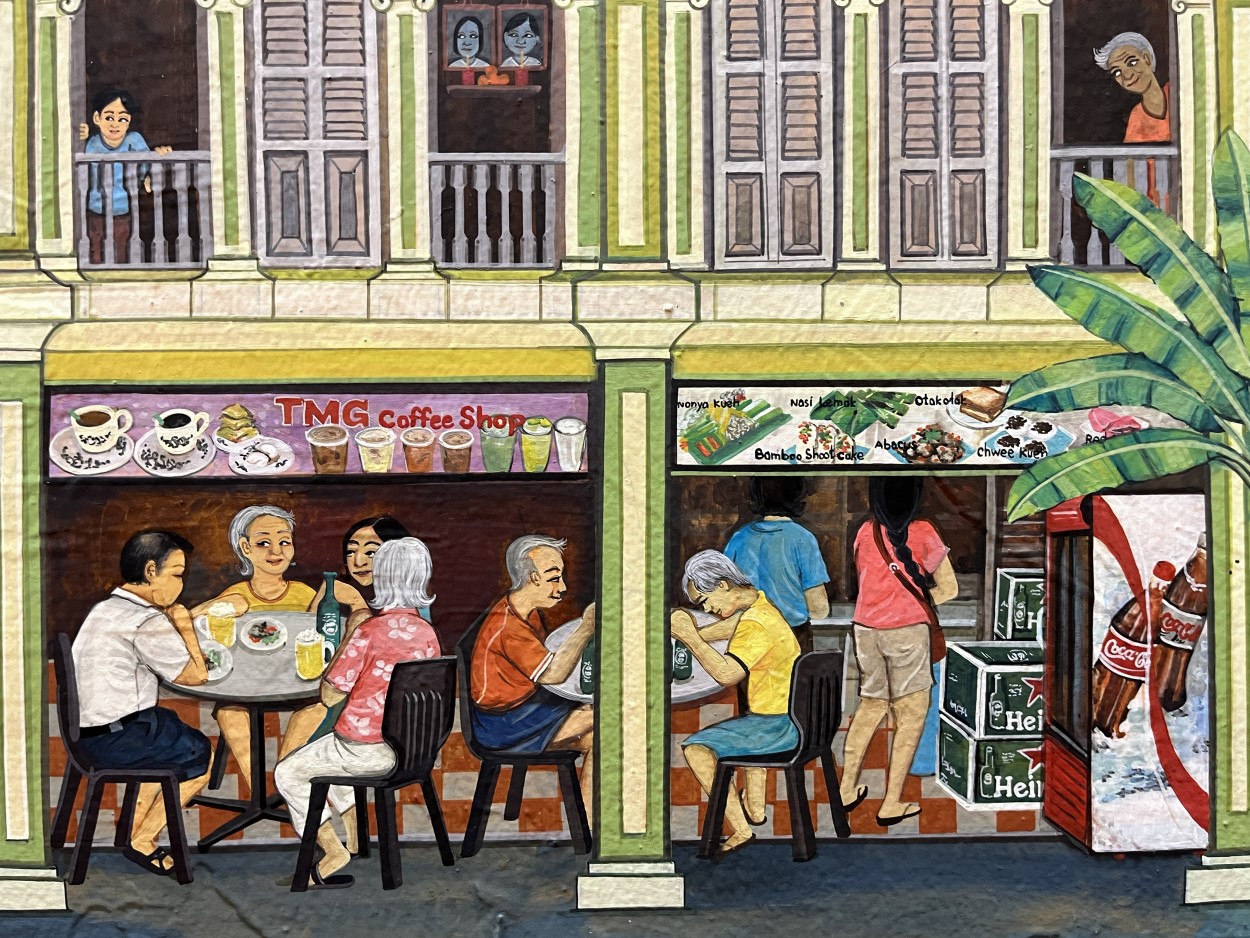

Hand-painted murals by two Thai artists in 2015 adorn every single one of the main shrine’s inner walls. At first glance, some of these seem nothing out of the ordinary as they depict Buddha’s life and teachings, and his path to enlightenment. But on closer scrutiny, familiar landscapes of Singapore can be seen.

For instance, behind the huge golden statue of Buddha in the main shrine – which looms on a platform the height of a grown man – the artists have incorporated scenes of Singapore. In a mural titled “Planes of Rebirth” depicting the different possible planes of existence in which Buddhist rebirth may take place, artists have painted the famous row of Koon Seng Road shophouses in all its various hues. This scene represents human activities and human desires as depicted by the people exercising in fashionable athletic wear, and children in superhero costumes.

To the right of the houses is a large colonial-style bungalow, with luxury cars parked in front and a woman with her husband carrying a child. This reminds the viewer to reflect on materialism, which seems trivial compared to the larger meaning of life exemplified by the other characters within the scene: two little girls in hijab holding hands, a grey-haired woman in a wheelchair and an old man walking on his own with a walking stick. The life stages of birth, ageing, sickness and death, also known as the “four sufferings” in Buddhism, are conveyed in this scene against the backdrop of Singapore.

And to the right of this is the seemingly innocuous scene of people in a local kopitiam (coffeeshop) having a meal and drinking beer. This scene reminds us again of what Buddhism defines as a vice: alcohol. Vices, on this plane of birth, are everywhere.

Chinese-style Columbarium

In Thailand, columbaria are typically found outdoors, where the ashes are stored inside exterior temple walls encircling the main shrine. The Chinese-style columbarium in the basement of the temple’s administrative office is another example of how Wat Ananda has become highly localised.

Just outside the space where rows of urns are kept is a space for ancestral tablets that are lined up in glass cases behind the statue of Kṣitigarbha, the ruler of the underworld and a common deity placed among ancestral tablets in Chinese temples. In front of the statue are offerings of fruit such as persimmons and oranges, common in traditional Chinese ancestral worship. On any given day, a filial descendant may be spotted burning joss paper in a designated area near the columbarium.

A Place for All

Wat Ananda commemorated its centenary in 2018, and its celebration lunch on 13 May was attended by then Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong, along with a delegation of some 630 Buddhist monks from Asia, Europe and America who were in Singapore for a monks’ conference.17

Today, both Thais and Singaporeans visit the temple to learn about Theravada Buddhism and participate in its activities. “I’ve been to Wat Ananda several times participating in religious activities, Thai cultural events and community events organised by the temple,” said Panalee Choosri, a Thai resident of Singapore and Counsellor at the Royal Thai Embassy. “It made me feel that Thai temples are an integral part of the local community in Singapore, benefiting and playing a role in uplifting the spirits and developing the Singaporean society,” she said.

She also noted how “Wat Ananda plays a crucial role in inviting the Thai and other ambassadors in Singapore, representing Buddhist countries such as Laos, Cambodia, and Sri Lanka, to visit the temple. This helps foster collaboration and unity among countries that follow the Buddhist faith”.18

Choosri is not alone in seeing Wat Ananda as place for promoting religious harmony and helping the underprivileged in Singapore. In fact, the temple readily welcomes non-Buddhists to participate in its events. For instance, its regular durian parties are attended by people of various faiths, all bonded together by their love for the fruit.19

“The temple has a relationship with Singaporeans, encouraging cooperation and mutual understanding through activities such as banquets for the elderly. The Thais residing and working in Singapore would come to serve the food, sing and create an ambience that fosters camaraderie. Every three months, the temple organises special activities. Volunteers bring food and rice to distribute to the elderly. Volunteers write to them to ask what they need, and the temple provides the supplies according to their wishes,” said Phramaha Rian Manone Yang, Assistant Chief Abbott and the temple’s Honorary Secretary.20

Said Liow Kok Ann, a volunteer treasurer with the temple for nine years: “It is a safe spiritual space not only for the Thais but also for the local communities to come together and appreciate and explore the different aspects of Thai culture and Buddhism.”21

Thammika Songkaeo is a Thai resident of Singapore and the creative producer of Changing Room (www.twoglasses.org), a dance film and interactive screening experience. Thammika holds a Master of Fine Arts degree in creative writing from Vermont College of Fine Arts. She is also an alumna of Williams College in Massachusetts and the University of Pennsylvania.

Thammika Songkaeo is a Thai resident of Singapore and the creative producer of Changing Room (www.twoglasses.org), a dance film and interactive screening experience. Thammika holds a Master of Fine Arts degree in creative writing from Vermont College of Fine Arts. She is also an alumna of Williams College in Massachusetts and the University of Pennsylvania.Notes

-

Buddhism has three major schools: Theravada, Mahayana and Vajrayana. Theravada Buddhism is the dominant form of Buddhism in Sri Lanka, Cambodia, Thailand, Laos and Myanmar. It is the official religion of Thailand. ↩

-

Ng Jun Sen, “Oldest Thai Buddhist Temple in Singapore Turns 100; PM Lee Attends Celebration,” Straits Times, 13 May 2018, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/oldest-thai-buddhist-temple-in-singapore-turns-100-pm-lee-attends-celebration. ↩

-

Anne M. Blackburn, “Ceylonese Buddhism in Colonial Singapore: New Ritual Spaces and Specialists, 1895–1935,” ARI Working Paper no. 184 (May 2012): 16–17, https://ari.nus.edu.sg/publications/wps-184-ceylonese-buddhism-in-colonial-singapore-new-ritual-spaces-specialists-1895-1935/. ↩

-

Wat Ananda Metyarama Singapore, Wat Ananda Metyarama Thai Buddhist Temple 100th Anniversary 1918–2018; Blackburn, “Ceylonese Buddhism in Colonial Singapore,” 17. ↩

-

Blackburn, “Ceylonese Buddhism in Colonial Singapore,” 17. ↩

-

Blackburn, “Ceylonese Buddhism in Colonial Singapore,” 17. ↩

-

“History,” Wat Ananda Metyarama Thai Buddhist Temple, accessed 27 March 2024, https://watananda.org/about-us/history/. ↩

-

“History.” ↩

-

Tay Suan Chiang, “Standing Tall,” Business Times, 12 July 2014, 8–9. (From NewspaperSG); Janice Seow, “Wat Ananda Metyarama Thai Buddhist Temple,” InDesignLive, 24 April 2014, https://www.indesignlive.com/singapore/project-news/wat-ananda-metyarama-thai-buddhist-temple. ↩

-

“About Us,” Wat Ananda Youth, accessed 27 March 2024, http://way.org.sg/?page_id=26. ↩

-

“The Seventieth Anniversary Celebrations of His Majesty the King’s Accession to the Throne,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Kingdom of Thailand, 19 June 2016, https://www.mfa.go.th/en/content/5d5bd00815e39c306001cf0f?cate=5d5bcb4e15e39c3060006838. ↩

-

Yeo Sam Jo, “Thais and Singaporeans pray for late Thai King Bhumibol Adulyadej,” Straits Times, 15 October 2016, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/thais-and-singaporeans-pray-for-late-thai-king. ↩

-

“Former Thai PM at Temple Ceremony,” Straits Times, 24 February 1986, 11. (From NewspaperSG); Wat Ananda Metyarama Singapore, Wat Ananda Metyarama Thai Buddhist Temple 100th Anniversary 1918–2018. ↩

-

Cheryl Sim, “Zhong Yuan Jie (Hungry Ghost Festival),” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published September 2020. ↩

-

Wat Ananda Facebook, 9 September 2023, https://www.facebook.com/Watananda/videos/838135267602336. ↩

-

Wat Ananda Facebook, 9 September 2023, video, 26:10, https://www.facebook.com/Watananda/videos/838135267602336. ↩

-

Ng, “Oldest Thai Buddhist Temple in Singapore Turns 100; PM Lee Attends Celebration.” ↩

-

Correspondence with Panalee Choosri, 19 January 2024. ↩

-

Suhaimi Yusof Instagram, 21 June 2022, https://www.instagram.com/p/CfEJYa5JfPm/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link; Charissa Yong, “Religious Leaders from Indonesia, Singapore Call for Greater Interaction to Strengthen Harmony,” Straits Times, 11 July 2017, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/religious-leaders-from-indonesia-singapore-call-for-greater-interaction-to-strengthen. ↩

-

Correspondence with Liow Kok Ann, 23 February 2024 ↩

-

Correspondence with Liow Kok Ann, 22 February 2024. ↩