All Smoke? Opium Propaganda in the Syonan Shimbun

Imperial Japan justified its occupation of Singapore with opium propaganda and prohibition promises.

By Hannah Yeo

The date: 8 March 1907. The location: Ipoh. A parade of enormous lanterns shaped as opium beds, pipes and lamps snaked through the town by torchlight, along with effigies of opium smokers. Nearly 40 former opium smokers who had broken free of their habit took part in the procession, shouting their gratitude for the anti-opium movement. Hundreds of real opium pipes surrendered by former smokers and two 70-year-old former addicts brought up the rear.1

This theatrical display was part of the first Conference of Anti-Opium Societies in the Straits Settlements and Federated Malay States – the largest ever recorded in the world at the time – with the participation of some 3,000 delegates from Penang, Singapore, Melaka, Selangor and Negeri Sembilan.2

By the turn of the 20th century, anti-opium sentiment was gaining ground in Malaya and on the world stage. As early as 1898, medical doctor Lim Boon Keng and lawyer Song Ong Siang had criticised the colonial government for drawing over half of its revenue from opium sales.3 “[W]e wish to call the attention of the Straits Government to its position in regard to the baneful habit of opium smoking, to the revenue which it derives from this luxury and to the duties which it morally owes to the poor and helpless victims of the opium habit,” Lim wrote in the Straits Chinese Magazine.4

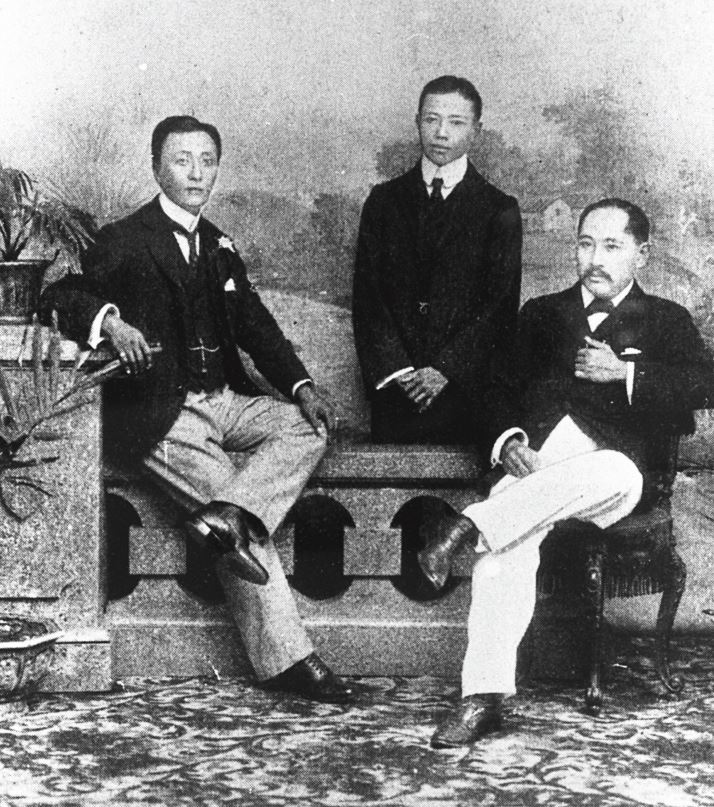

Prominent members of the Chinese community, Song Ong Siang (left), Wu Lien-Teh (centre) and Lim Boon Keng (right), aimed to eradicate opium addiction in Singapore in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Prominent members of the Chinese community, Song Ong Siang (left), Wu Lien-Teh (centre) and Lim Boon Keng (right), aimed to eradicate opium addiction in Singapore in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.When it was clear that the colonial government was not listening, Lim’s medical partner Wu Lien-Teh raised the issue at an anti-opium meeting in London in 1907. There, to his surprise, “speaker after speaker railed at its [the opium trade’s] iniquities and demanded stoppage of further traffic between India and China,” he wrote in his memoir. “I gave up my notes and spoke impromptu when describing conditions in the Straits Settlements… [and] received continued ovation from the 500 persons assembled.” Wu’s petition was brought before Winston Churchill, then Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies. Churchill assured him that the “Home Government was not indifferent, but that it was only possible to move step by step in the Colonies in view of the vast interests involved”.5

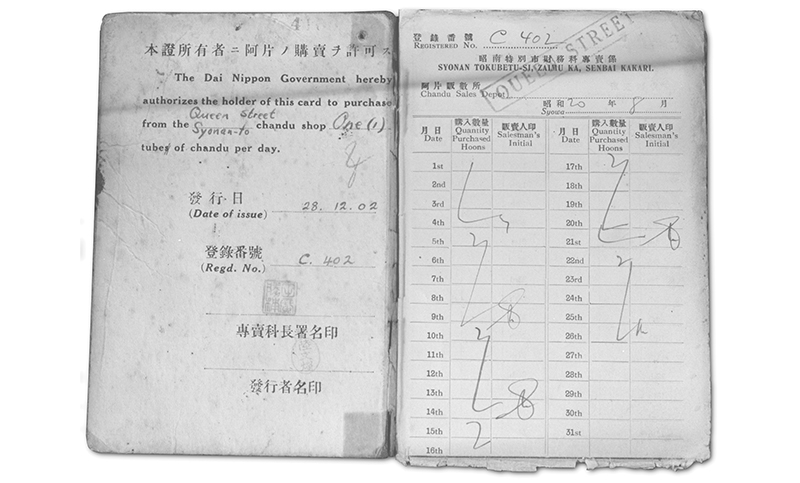

The Straits government was in no hurry to ban opium. Despite Britain’s participation in international conferences and treaties, colonial governors believed prohibition was ineffective in reducing addiction. To protect opium revenue while appeasing diplomatic pressure, the Straits government monopolised the opium business, opening government-controlled shops where registered smokers could buy rationed tubes of opium. An Opium Revenue Replacement Fund was also established in 1925 to hedge against expected revenue loss. Amid growing pressure by the United States for a complete ban on opium, the Home Office admitted Britain’s stance was “an equivocal and an embarrassing one”.6

A postwar report estimated there were still 16,500 active smokers on government record in Singapore at the end of 1941. This figure, however, was highly disputed as it did not account for illegal smuggling or redacted smokers.7

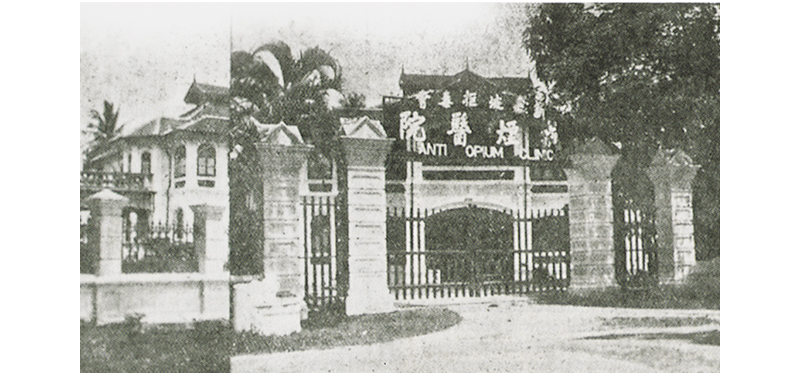

In his 1935 study, President of the Singapore Anti-Opium Society Chen Su Lan put conservative estimates at one in four Chinese adults in Malaya being opium addicts.8 Chen, a medical doctor and third-generation Methodist, described addicts as slaves of opium in need of salvation:

“Day by day we hear of wives, mothers and children being left to starve while the bread-winners of the family spend their time smoking opium… [The Anti-Opium Clinic] is the only place where they can rid themselves of the opium poison and gain their liberty and freedom from their cruel master… OPIUM.”9

Peddling Propaganda

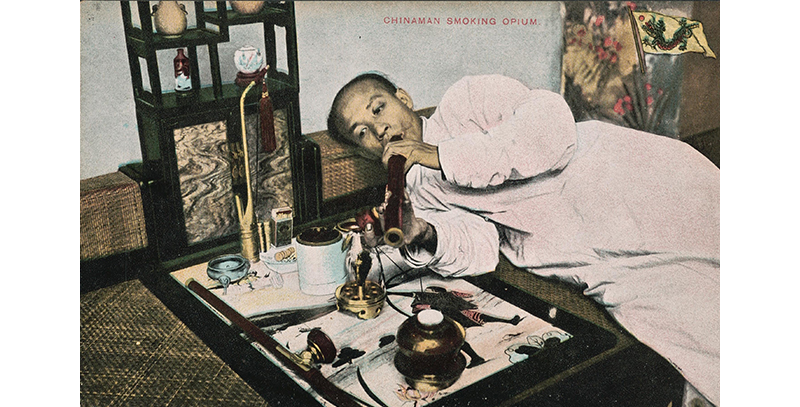

The problem of opium addiction in Malaya was well known internationally by the time the Imperial Japanese Army crossed the causeway into Singapore. Long aware of the problem of opium addiction in Asia, Japan used this to their advantage as well as to justify their invasion of China and Malaya as one of emancipation from Western oppression. In Singapore, this same narrative was communicated through newspapers.

The Syonan Shimbun (published from 20 February 1942 to 4 September 1945) was the only English-language newspaper available in Singapore during the Japanese Occupation.10 Although known to be a propaganda paper, the Japanese authorities’ tight ban on listening to the radio and the ban on Western broadcasts meant that people in Malaya turned to the newspaper to get a sense of how the war was unfolding.

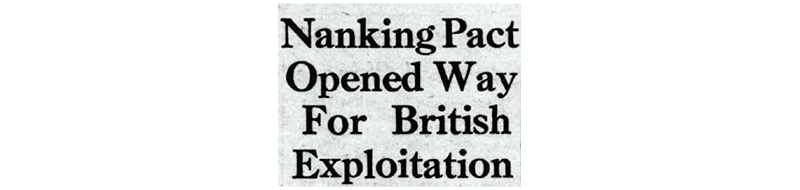

Across the 43 months of occupation, the Syonan Shimbun carried over 80 articles with titles such as “Britain’s Opium Policy in China Condemned” and “Opium War Most Disgraceful Chapter in British History”.11

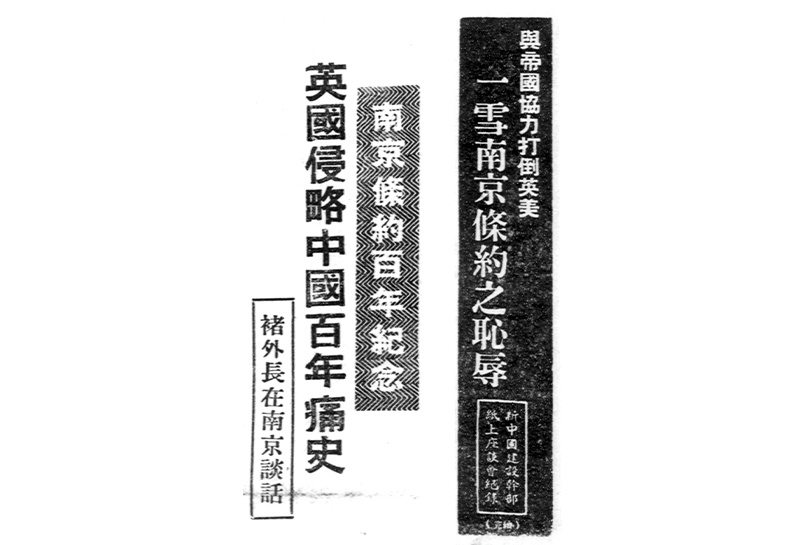

The Chinese edition, Zhao Nan Ri Bao (昭南日报), carried similar articles, often syndicating them from the state-controlled Domei News Agency in Shanghai, Nanjing and Tokyo. Examples include《南京条约百年纪念–反英与亚运动强烈展开》(Nanjing Treaty Centennial – Pan-Asian Anti-British Campaign Intensifies) published on 25 August 1942,《南京条约百年纪念–英国侵略·中国百年痛史》(Nanjing Treaty Centennial – China’s 100 Years of Pain from Britain’s Aggression) on 27 August 1942 and《与帝国协力打倒英美–雪南京条约之耻辱》(Join Forces with the Empire to Defeat the Anglo-Americans and Erase the Shame of the Nanjing Treaty) on 28 August 1942.

To win over the community in Singapore, two opium propaganda strategies were implemented. First, an anti-Anglo-American campaign timed with the centennial of the Treaty of Nanking was launched a few months after Japan’s takeover. Having established Britain as the villain, Japan positioned itself as the forerunner of Asian emancipation through success stories of opium suppression and treatment in its colonies. Its goal was to justify Japan’s aggression as a war of liberation and convince subjugated populations to work with Imperial Japan as part of the New Order, later known as the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.12

Campaign Centennial

“[T]he primary cause for the outbreak of the present war ‘can be traced directly to the rampant encroachments by Britain and the United States upon East Asia these past decades’,” said Japanese Foreign Minister Shigenori Togo in a speech before the Institute of Pacific Relations, as reported by the Syonan Shimbun on 12 May 1942. He recalled that “Britain following the shameful Opium War extensively exploited China with Hong Kong as its stronghold”.13

His speech set the tone for a rapid series of articles on opium timed with the 100th anniversary of the Treaty of Nanking. Signed on 29 August 1842 between Great Britain and the Qing dynasty, the treaty gave British subjects the right to live and trade in five Chinese port cities (Canton, Amoy, Fuzhou, Ningbo and Shanghai), ceded Hong Kong to Britain and demanded 21 million dollars from China as war compensation, in return for Britain ending hostilities in what is now known as the First Opium War.14

Between 26 August and 3 September 1942, 13 more articles zeroed in on the Opium War and Treaty of Nanking as part of the “Anti-British and East Asia Development Week” commemorating the treaty’s centenary.15 The articles drew battle lines between the East and the West.

On 30 August, the newspaper carried reports on the comments by Tomokazu Hori, head and spokesperson of the Board of Information, and former premier Koki Hirota on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the Treaty of Nanking. Hori called the Opium War and the treaty the most “disgraceful and ugly chapters in British history”. Rousing “the people of China, India and other countries exploited by Britain” to “meet them squarely”, he argued that British exploitation would never end otherwise. “Is it really possible for the British who for the past 100 years have regarded the Chinese people as uncivilised people regard the Chinese as equal to themselves and respect Chinese cultural equality? Nonsense! All their lip services will disappear instantly when the necessities cease.”16

Hirota presented Japan’s alternative to British imperialism. He said that Japan’s New Order in East Asia would be “characterised by peace and love of humanity” with “genuine mutual assistance among the various races, instead of the conception of power and supremacy based on power”.17

On 3 September, the paper published a scathing report on the Opium War and wrote that the Nanking Treaty had “brought China down from an Empire to a third class nation dominated and controlled by Britain, which condition lasted until the China Incident when Nippon started her war of liberation, which would ensure that never again would any Asian nation be so humiliated”. The paper added that “millions of opium sodden Chinese have paid the price demanded by Britain in her policy of drugging the people of a nation into senselessness in order to render them helpless against her methods of exploitation”.18

In the crucible of war, Japan linked its occupation of Malaya to the historical struggle against British imperialism, framing the Pacific War as a continuation of the Opium War.

Prohibition Promises

When the tirade against the Opium War ended, a new narrative emerged – promises that Japan would eradicate opium addiction by setting up opium clinics and creating antidotes in the territories they had seized.

The Syonan Shimbun cited Japan’s puppet state of Manchukuo in Manchuria as a model example of how the government had taken gradual steps to prohibit opium smoking. “All habitual smokers have been registered and nearly 40 clinics to cure addicts have been established,” the paper reported.19 Through the efforts of the Opium Prohibition Bureau and the Opium Law, the paper wrote that the number of opium smokers in Manchukuo had dropped from 1.3 million in 1937 to 508,000 in 1942.20

In Malaya, the Japanese authorities aimed to gradually reduce opium smoking by limiting the amount of opium people could buy, “supplying just sufficient quantities to keep addicts from resorting to faked drugs which are more poisonous”.21 The Syonan Shimbun carried reports of local leaders praising Japan for solving the opium problem.

“Everybody welcomes the policy of the Nippon authorities,” were the words of Lim Boon Keng, who was also a leader of the Chinese community. Eurasian leader Charles Paglar said: “It will take some time to cure addicts without injurious results. Nippon-xin can safely do it in the most efficient manner.” “Even if [the policy] causes… some loss in the revenue, no good Government could possibly enrich itself at the expense of the health of the people whom they are to govern,” said S.C. Goho, leader of the Indian community.22

Naturally, these endorsements cannot be taken at face value as prominent men like Lim and Paglar were forced to serve as Japanese mouthpieces. Mamoru Shinozaki, who was the chief education officer and chief welfare officer during the Japanese Occupation of Singapore, noted that he had, on one occasion, given each community leader “a slightly different version of [a] message which [he] wrote [himself]. The leaders had to read these messages to carry out [his] orders”.23

Opium on the Big Screen

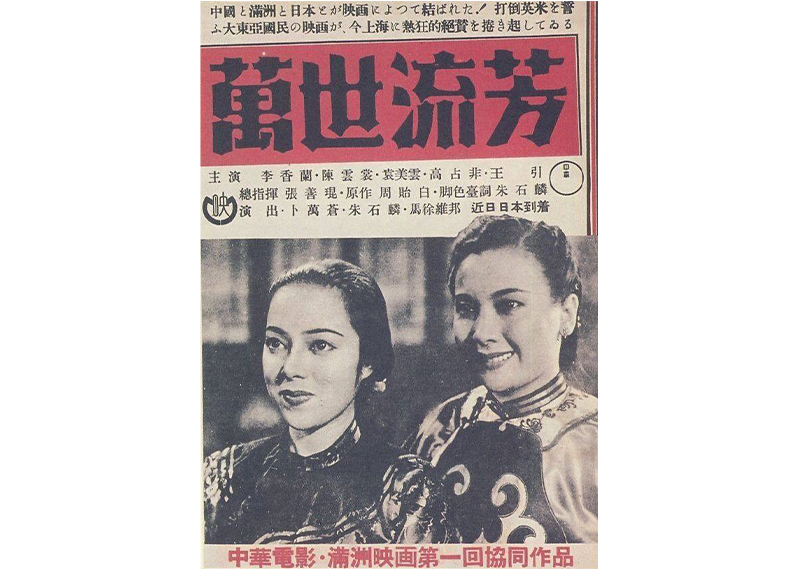

Articles in the Syonan Shimbun reveal that Japan knew the seriousness of the opium problem and held it as an emotive point on which loyalties could turn. Besides news articles, propaganda films about the First Opium War were screened at the Kyoei Gekkyo (the former Capitol Theatre) from 1943 to 1944.24 Advertisements for《阿片戦争》(The Opium War) and《万世流芳》(Eternity) appeared in the Syonan Shimbun and Zhao Nan Ri Bao. 《万世流芳》is a romantic historical drama about statesman Lin Zexu, whose destruction of British opium catalysed the First Opium War. Produced in Japan-occupied Shanghai by the Manchurian Motion Picture Association and China United Productions for the 100th anniversary of the Treaty of Nanking, the film was well-received for its anti-imperialist theme and star-studded cast.25

Retired teacher Wong Hiong Boon, who was 11 at the time, remembers it was one of the most popular films. Lead actress Li Xianglan (also known as Yoshiko “Shirley” Yamaguchi) was a “very good singer, her songs were very popular and everyone [was] singing her song about giving up opium smoking”, he said in an oral history interview.26

Unveiling the Smokescreen

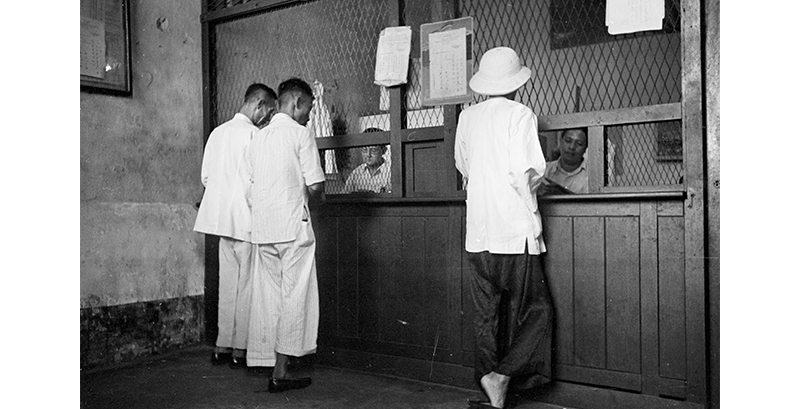

In reality, however, opium was too lucrative a business to stop. The Japanese administration continued the British policy of selling opium under a monopoly in government retail shops and repaired the opium factory at the foot of Bukit Chandu in Singapore.27 Although the Japanese permit for opium was easily attainable, public access to the drug was restricted by supply and demand.28

Between 1942 and 1944, opium rations were halved from 60 tubes (each containing two hoon or 0.77 g of opium) to 30 tubes per month because stock had run out.29 This drove even more addicts to the booming wartime black market, where they could buy opium from smugglers, dealers working with Japanese soldier-carriers, or those who would trade their drug ration for food.

A 1958 study by medical doctor Joseph Leong Hon Koon for the United Nations reported that the “addict population at the end of the war was approximately 16,000 in Singapore alone”. But taking into account the unrecorded illicit drug trade, others estimate this figure to be almost as high as 30,000.30 For all its propaganda, Japan’s New Order was little different from the self-interested spectre it had painted of Britain’s Empire. In fact, Imperial Japan had long been raising opium revenue through farms in their colonies of Formosa (now Taiwan) and Manchuria before the war.31

Ironically, the accusations Japan had levelled against Britain for encouraging opium-smoking were levelled at Japan by the victors of war.32 At the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal, the United States called out opium dealing as imperial exploitation, an intentional means of financing wars of aggression and enforcing servility in occupied territories.33

Governments could no longer argue that raising revenue from opium was morally defensible. On 1 February 1946, the Opium and Chandu Proclamation for “the suppression of opium smoking” was published in the Singapore Gazette. Section 3 stipulated that “any person who has in his possession or under his control any opium or chandu or opium pipe, lamp or opium cooking utensil shall within fourteen days from the commencement of this Proclamation surrender the same to a Chandu Officer at any Customs Office or at any Police Station of the Civil Affairs Police”.34

In the end, it was not only Japan’s promises of an opium-free New Order, but the entire enterprise of international opium trade that went up in smoke.

Sung by Li Xianglan

Da, oh Da, won’t you wake up.

Why do you still think about opium?

It drains your spirit, ruins your years

Your career goes up in smoke,

the sacrifice is terrible,

You exchange your whole life for sand,

the price is too great.

Even if opium is your lover,

you should still let go of it!

Opium is actually your enemy, and my enemy too.

Da, oh Da, why do you still think about it?

If you really love me, listen to me, don’t think about opium from now on.

达呀达,你醒醒吧,你为什还想着它,

它耗尽了你的精神,断送了你的年华,

你把一生事业作烟霞,这牺牲未免可怕,

你把一生心血换泥沙,这代价未免太大。

它就是你的情人,你也该把它放下,

何况是你的冤家,也是我的冤家。

达呀达,达呀达,你为什还想着它,

你要真爱我,要听我的话,从今以后别再想着它。

Source: “戒煙歌 - 李香蘭 Li Xiang Lan (山口淑子 Yoshiko Yamaguchi),” YouTube, 3 April 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3DzRMDKXEm8.

[Transcribed and translated by Hannah Yeo]

Hannah Yeo is a Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. Her responsibilities include collection development and research on topics relating to Singapore and Southeast Asia.

Hannah Yeo is a Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. Her responsibilities include collection development and research on topics relating to Singapore and Southeast Asia. Notes

-

“The Anti-opium Crusade,” Pinang Gazette and Straits Chronicle, 9 March 1907, 4; “Anti-opium Conference,” Straits Echo (Mail Edition), 15 March 1907, 211. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Jayakumary Marimuthu and Mohd Firdaus Abdullah, “Opium Smoking Suppression Campaigns and the role of Anti-Opium Movements in the Federated Malay States, 1906–1910,” Jebat: Malaysian Journal of History, Politics & Strategic Studies 47, no.3 (2020): 41–42, https://journalarticle.ukm.my/17094/1/44772-144085-1-SM.pdf. ↩

-

On average, the Straits Settlements of Singapore, Penang and Melaka generated 49 percent of their annual revenue from opium farming between 1898 and 1906 at least. See Song Ong Siang, One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore: The Annotated Edition (Singapore: National Library Board and World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd., 2020), 629. (From NLB OverDrive); Carl A. Trocki, Opium and Empire: Chinese Society in Colonial Singapore, 1800–1910 (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1990), 2. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 305.895105957 TRO) ↩

-

Lim Boon Keng, “The Attitude of the State Towards the Opium Habit,” The Straits Chinese Magazine: A Quarterly Journal of Oriental and Occidental Culture 2, no. 6 (June 1898): 47. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RRARE 959.5 STR; microfilm no. NL267). Lim Boon Keng, Song Ong Siang and Wu Lien-Teh were the editors of the magazine. ↩

-

Wu Lien-Teh, Plague Fighter: The Autobiography of a Modern Chinese Physician (Penang: Areca Books, 2014), 245–46. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSEA 610.92 WU); Song Ong Siang, One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore (Singapore: University of Malaya Press, 1967), 438. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 SON) ↩

-

Harumi Goto-Shibata, “The International Opium Conference of 1924–25 and Japan,” Modern Asian Studies 36, no. 4 (October 2002): 976–77. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website); John Collins, “Drug Diplomacy from the Opium Wars through the League of Nations, 1839–1939,” Cambridge University Press, 25 November 2021, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009058278.002; William B. McAllister, Drug Diplomacy in the Twentieth Century: An International History (London; New York: Routledge, 2000), https://archive.org/details/drugdiplomacyint0000mcal. ↩

-

Derek Mackay, Eastern Customs: The Customs Service in British Malaya and the Opium Trade (London; New York: Radcliffe Press, 2005), 150. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSEA 352.44809595109041 MAC) ↩

-

Chen Su Lan, The Opium Problem in British Malaya (Singapore: Singapore Anti-Opium Society, 1935), 1. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RRARE 178.8 CHE; microfilm no. NL7461) ↩

-

Chen Su Lan, Opium Is a Deadly Poison: An Ad Interim Report May 8th to December, 1933 (Singapore: The Anti-Opium Clinic, 1934), 1. (From NUS Libraries) ↩

-

The first issue of the paper, published on 20 February 1942, was called The Shonan Times. It was renamed The Syonan Times the next day. On 8 December 1942, it was renamed The Syonan Sinbun. On 8 December 1943, the paper was renamed The Syonan Shimbun and retained this name until its last issue on 4 September 1945. A Chinese edition, Zhao Nan Ri Bao (昭南日报), was introduced on 21 February 1942. See Lee Meiyu, “Propaganda Paper,” BiblioAsia 11, no. 4 (January–March 2016): 40–41. ↩

-

“Britain’s Opium Policy in China Condemned,” Syonan Shimbun, 29 August 1942, 4; “Opium War Most Disgraceful Chapter in British History: Our Spokesman Points Out Enemy’s ‘Trait of Ruthless Exploitation’,” Syonan Shimbun, 30 August 1942, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

The New Order, later known as the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, was Imperial Japan’s empty promise to unite territories in East and Southeast Asia under justice, peace and economic cooperation. In reality, it enabled Japan to advance their wartime interests under the guise of mutual benefit. ↩

-

“Present East Asia War Due Entirely to British and American Encroachments,” Syonan Shimbun, 12 May 1942, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Julia Lovell, The Opium War: Drugs, Dreams and the Making of China (London: Picador, 2012), 238–40. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. R 951.033 LOV) ↩

-

“Nanking Launches Anti-British And Development of East Asia Week,” Syonan Shimbun, 26 August 1942, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Opium War Most Disgraceful Chapter in British History”; “Tomokazu Hori Passes Away,” Syonan Shimbun, 27 March 1944, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Domei Tokyo, “Mr. Hirota Sees New Era of Peace And Prosperity For East Asia,” Syonan Shimbun, 30 August 1942, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Opium As an Aid to British Exploitation,” Syonan Shumbun, 3 September 1942, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Charles Neil, “The New Order,” Syonan Shimbun, 1 April 1942, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Considerably Fewer Opium Smokers in Manchoukuo,” Syonan Shimbun, 30 August 1942, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Nippon Opium Policy in Malaya Contradicts Anglo-American Lies,” Syonan Shimbun, 26 September 1942, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Community Leaders Praise Authorities’ Opium Policy: Evil to Be Stamped Out by Gradual Curing of Addicts,” Syonan Shimbun, 27 September, 1942, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Mamoru Shinozaki, Syonan, My Story: The Japanese Occupation of Singapore (Singapore: Times Books International, 1982), 152. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.57023 SHI-[JSB]). These messages were read out in praise of the Japanese Emperor during his birthday celebrations. ↩

-

Chan Kwee Sung, “Capitol Screened Japanese Movies,” Straits Times, 8 January 1999, 66. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Jie Li, “A National Cinema for a Puppet State: The Manchurian Motion Picture Association,” in The Oxford Handbook of Chinese Cinemas, ed. Carlos Rojas and Eileen Cheng-yin Chow (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019), 79, 89. (From Central Public Library, library@chinatown and Punggol Regional Library, call no. 791.430951 OXF-ART]); “Film Shows Chinese Revolt Against British Imperialism,” Syonan Shimbun, 13 May 1943, 2; “Story of Britain’s Introduction of Opium into China,” Syonan Shimbun, 3 August 1944, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Wong Hiong Boon, oral history interview by Mark Wong, 8 June 2010, MP3 audio, 3:00–3:25, Reel/Disc 2 of 9, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 003526). ↩

-

Diana S. Kim, Empires of Vice: The Rise of Opium Prohibition Across Southeast Asia (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2020), 189. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 364.1770959 KIM). The factory had been partially destroyed during bombings in December 1941. ↩

-

Mackay, Eastern Customs: The Customs Service in British Malaya and the Opium Trade, 152; Pung Eng Huat, “A Research Paper on the Opium Addict: The Nature and Extent of Opium Addiction in Singapore and the Measures in Force to Rehabilitate the Addict” (Thesis, University of Malaya, Social Studies Course, 1957), 29. ↩

-

This conversion from hoon to gram is based on Chen Su Lan’s book, The Opium Problem in British Malaya, where 4 chi (40 hoons) is given as 8/15 ounce. ↩

-

Lim Thean Soo, Sukumaran Nair and S. Mohd. Razak, The Impact of Customs (Singapore: Singapore National Printers, 1974), 11. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 336.26095957 LIM); Leong Hon Koon, “The Opium Problem in Singapore,” United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, January 1958, https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/bulletin/bulletin_1958-01-01_4_page003.html. ↩

-

Carl A. Trocki, Opium, Empire, and the Global Political Economy: A Study of the Asian Opium Trade, 1750–1950 (London: Routledge, 1999), 88–89. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. R 363.45095 TRO); Hans Derks, History of the Opium Problem, The Assault on the East, ca. 1600–1950 (Leiden: Brill, 2012), 495. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSEA 363.450950903 DER) ↩

-

Neil Boister, “Colonialism, Anti-Colonialism and Neo-Colonialism in China: The Opium Question at the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal,” in War Crimes Trials in the Wake of Decolonization and Cold War in Asia, 1945–1956, ed. Kerstin von Lingen (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), 32. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSEA 345.01 WAR) ↩

-

Noorman Abdullah, “Exploring Constructions of the ‘Drug Problem’ in Historical and Contemporary Singapore,” New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies 7, no. 2 (December 2005): 48, https://www.nzasia.org.nz/uploads/1/3/2/1/132180707/7_2_4.pdf; Reiji Yoshida, “Japan Profited as Opium Dealer in Wartime China,” Japan Times, 30 August 2007, https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2007/08/30/national/japan-profited-as-opium-dealer-in-wartime-china/. The International Military Tribunal for the Far East, also known as the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal, convened on 29 April 1946 and lasted until 12 November 1948. It was created to prosecute the leaders of Japan for their war crimes, crimes against peace and crimes against humanity leading up to and during World War II. ↩

-

“Notice: Opium and Chandu Proclamation,” Straits Chronicle, 11 February 1946, 2; “Suppressing Opium Smoking,” Straits Times, 4 February 1946, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩