The Story of Sembawang from 19th-Century Singapore Maps

Sembawang’s history can be told through the many maps that have charted its changes over the years.

By Makeswary Periasamy

Today, people are attracted to Sembawang for a number of reasons. Families visit the beach there to have a picnic or barbeque, and fishing enthusiasts congregate at the jetty hoping to score a good catch. Sembawang is also well known for its hot spring – with supposed health properties – that brings people from all over Singapore to the north to enjoy a leisurely foot bath.1

In the 19th century, however, Sembawang looked very different. Located at the northernmost tip of Singapore facing the narrow Selat Tebrau, or Strait of Johor (erroneously labelled as Old Straits of Singapore on some early maps),2 Sembawang once had vast swathes of dense forest before these were cleared for the cultivation of cash crops like pepper, gambier (pale catechu), coconut and rubber in the early 19th century. The plantations subsequently gave way to Chinese and Malay villages.

Origin of “Sembawang”

Sembawang is a Malay word for a timber tree which grows in wet tropical areas especially along streams and flowing rivers in forests.3 The first record of the tree specimen in Singapore was by Danish surgeon Nathaniel Wallich in 1822, who named it Mesua singaporiana.4 In 1897, the tree was recorded as Kayea ferruginea by Henry Nicholas Ridley, then the director of the Singapore Botanic Gardens, who also noted its local name, Pokok Sumbawang, as well as its proximity to Johor.5 In his book, The Flora of the Malay Peninsula published in 1922, Ridley described the Kayea ferruginea as a “fairly large straggling tree… [found] overhanging streams and rivers in forests” whose local Malay name is “Buah Sembawang”.6

Now the tree is simply known as the Sembawang tree. It is generally accepted that the name “Sembawang” originated from this tree. It is also likely that the tree was found growing along the Sembawang River (Sungei Sembawang), which shares its name.

When the British first arrived in Singapore in 1819, it was sparsely populated and a large part of the island was covered with primeval forests. They also encountered 20 gambier and pepper plantations owned by Teochew planters who had arrived from Riau.7

Although these plantations were initially located near the Singapore River at the southern part of the island, they moved further inland to the north when agricultural land in the town centre became scarce due to the development of the town and harbour area. As gambier and pepper plants were harvested through a shifting cultivation method, these require new land every 15 to 20 years.8

Crops were planted along navigable rivers, which served as a mode of transportation. Prior to the cultivation of gambier and pepper plantations, Sembawang was covered with lush vegetation such as freshwater swamps, mangrove or coastal forests like the rest of the island. These were depleted by agricultural cultivation and human settlements over the decades.9

Early Surveys of Singapore

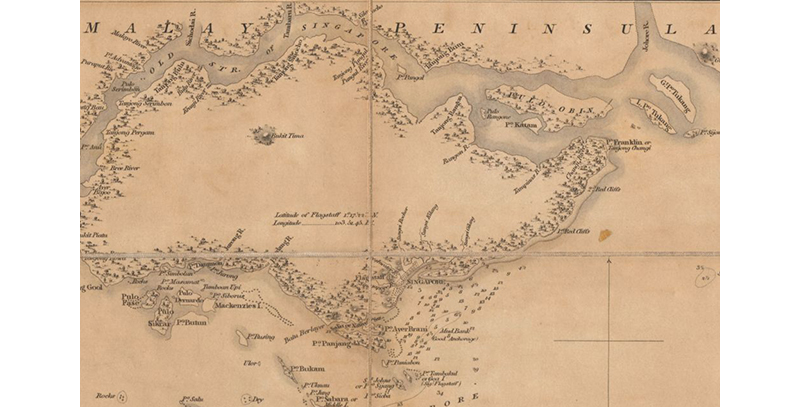

As early as 1822, Captain James Franklin surveyed the coastlines of the main island of Singapore. The results of his surveys were incorporated into a map, Plan of the Island of Singapore Including the New British Settlements and Adjacent Islands, produced by William Farquhar, the first Resident of Singapore, in 1822.10 Farquhar’s map was subsequently published as an inset, Sketch of the Island of Singapore, within an 1829 map of Sumatra by the Irish orientalist and linguist William Marsden.11

Although Sembawang is not named on these two maps, they show the coastal areas of the island of Singapore being covered with vegetation, a likely reference to the mangrove and freshwater swamp forests as well as the gambier and pepper plantations12 that existed in the early 19th century.13 The inset in Marsden’s map also features coconut trees along the island’s coastlines, including the Sembawang coastal area.14

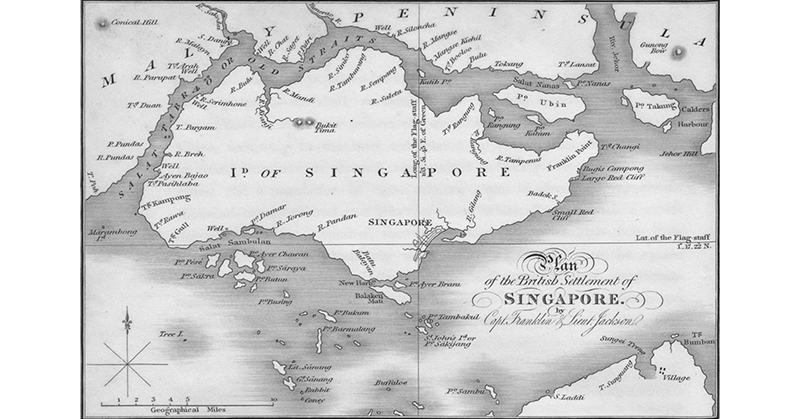

In 1828, Franklin, together with engineer and land surveyor Lieutenant Philip Jackson, prepared Plan of the British Settlement of Singapore, the first map to accurately capture the outline of Singapore island and possibly contains the earliest reference to the Sembawang area. The map shows several rivers throughout the island, including a “R. Tambuwang” in the north, most likely a corruption of the toponym, River Sembawang.15 (Other variant spellings of Sembawang in the 19th century include “Sumbawang” or “Sambawang”.)

During the 1830s and 1840s, several topographical surveys were conducted, but most of the maps of Singapore produced at the time tended to focus on the harbour and the town and its environs. The few maps that were produced of the entire island after 1828, such as the 1830 Sketch of the Island of Singapore and the 1836 Chart of Singapore Strait the Neighbouring Islands and Part of Malay Peninsula, did not indicate Sembawang River, and instead featured the adjacent Sinocho (Senoko) and Pungul (Punggol) rivers.16

When John Turnbull Thomson was Government Surveyor of the Straits Settlements (1841–55), he conducted extensive surveys of the interior of Singapore island as well as the surrounding waters. One of Thomson’s key tasks was to map the pepper and gambier plantations throughout the island and draw up boundaries of the various lots. This was needed for registering the plantations, which had different owners, and for issuing grants for the use of the land as well as to solve disputes that may arise.

The “Kang” in Sembawang

Thomson also surveyed the various streams and creeks near where most of the plantations were sited and noted the kang there. Kang refers to Chinese settlements by the river with a headman known as kangchu (港主; “owner of the river”). The headmen were usually the plantation owners, who took charge of the coolies (labourers) employed at the plantations.17

In his official report submitted in April 1848, Thomson noted that the Sembawang River is “navigable by the gunboats at high water” and that the area was “inhabited by Chinese gambier planters, who possessed one pukat” (pukat refers to a large native boat used for shipping gambier between Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore).18

Unlike the town and municipal areas which were more developed, the interior of the island of Singapore was heavily forested with no proper roads. Travelling by boat was a common mode of transport in the 19th century.

In his report, Thomson mentioned that the Chinese (mostly unmarried males) formed the bulk of the population in the north and interior of the island. He also listed 15 kang and the names of the Chinese headmen.19

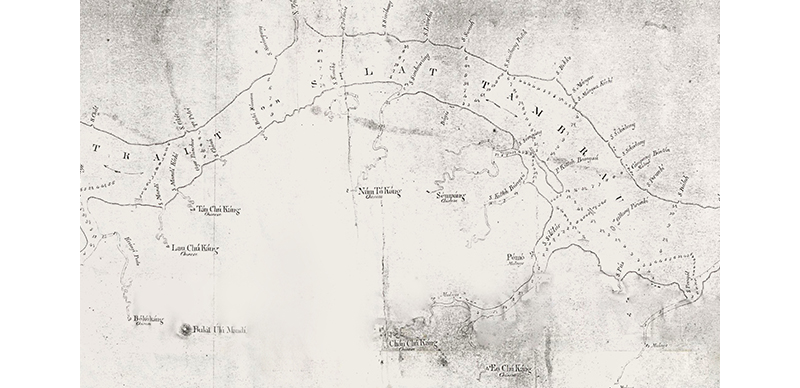

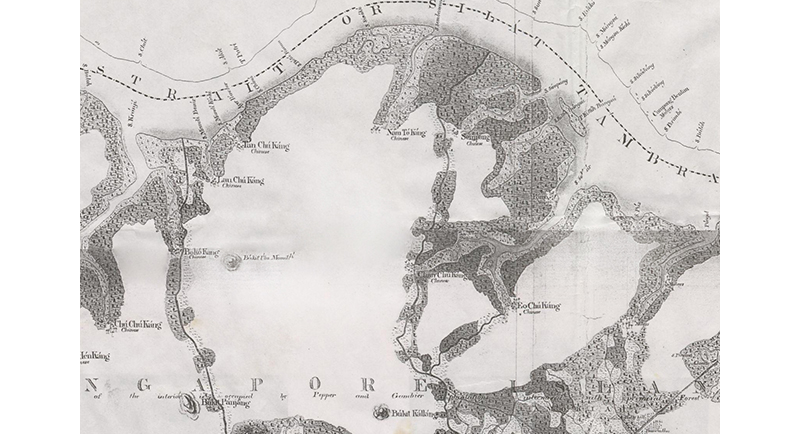

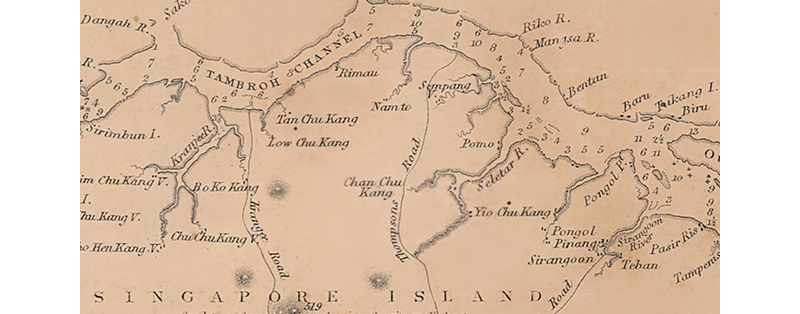

After completing his survey of the rivers that flowed into the Johor Strait, Thomson produced the Map of the Old Straits or Silat Tambrau and the Creeks to the North of Singapore Island in 1848.20 It is one of the earliest maps to feature the kang in the northern part of Singapore. Shown on the map, at the foot of Sembawang River, is Nám Tó Káng (烂土港), whose headman, according to Thomson, was Tan Ah Toh.21

A survey conducted in 1855 revealed that Sembawang comprised mostly gambier and pepper plantations. The survey recorded 10 of such plantations in Nám Tó Káng, which employed 137 coolies. Besides gambier and pepper, there were also indigo plants in Nám Tó Káng.22

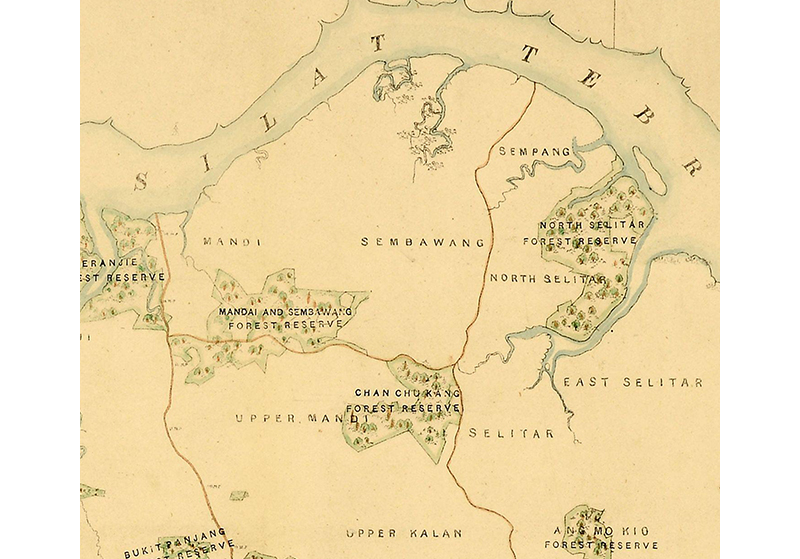

By the late 19th century, gambier and pepper plantations were mainly found in the northern and western parts of Singapore where the soil conditions were more favourable. Due to the constant felling and depletion of timber trees for lucrative cash crops, in 1883, the colonial government created forest reserves for two reasons – to protect the virgin forest reserves and also for a continuing supply of timber.23 In 1884, the first eight forest reserves were identified and administered, including in Sembawang.24 By 1889, the forest reserve in Sembawang occupied 379 ha (3.79 sq km).

In 1903, Nám Tó Káng was described as having two Chinese huts, one mile apart, in a jungle area.25 These huts, known by the Malay term bangsal, referred to both the plantation as well as the large attap building where the plantation owner and the coolies resided and processed the gambier.

Villages soon replaced the plantations. By the 1960s, the number of villages in the Sembawang area had expanded to eight.26 Unlike the kang whose inhabitants comprised Chinese male plantation workers, the villages were inhabited by families (sometimes of mixed ethnicities) who had access to basic amenities such as shops and schools.

In November 1968, the Sin Chew Jit Poh Chinese newspaper reported that Nám Tó Káng had become a large village and was renamed first as 水池村 (“reservoir village”) and later Ulu Sembawang (淡水港). It described the villagers as a mix of Chinese dialect groups, with the majority belonging to the Min (Hokkien) dialect group.27

Sembawang District

The present Sembawang town is bounded by the Strait of Johor to the north, Simpang to the east, Woodlands to the west, and Mandai and Yishun to the south. However, early maps of Singapore reveal that Sembawang covered a much larger area than now, which included parts of Woodlands and Mandai. In the present day, Sembawang occupies a smaller area although it stretches beyond Sembawang Road into parts of Simpang and Seletar.

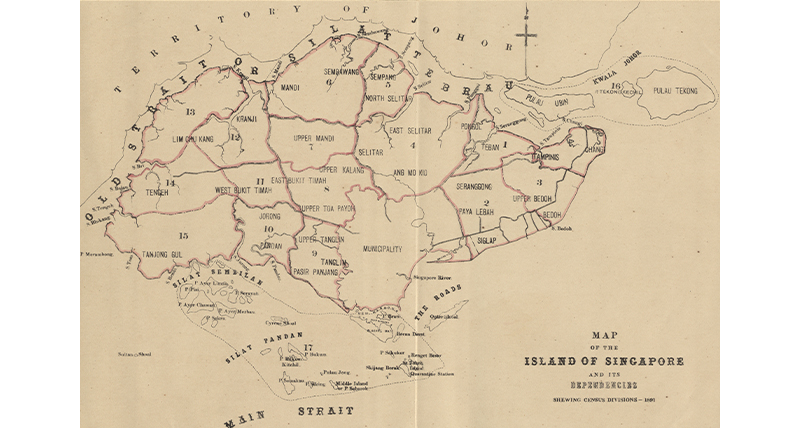

One of the earliest maps to name the area as “Sambawang” is the 1873 Map of the Island of Singapore and Its Dependencies prepared by the Surveyor-General’s Office of the Federated Malay States and Straits Settlements. An area occupying about two-thirds in the north – stretching from Sembawang Road to Bukit Timah Road – is indicated as “Mandai and Sambawang”.28 Prior to this, maps did not name the places on the island but featured the kang and rivers only.

From the mid-1880s, maps began to indicate Mandai and Sembawang as separate areas. An 1886 map, originally enclosed with the Annual Report of the Forest Department, Straits Settlements, is one of the first to feature “Sembawang” in its current spelling. It shows the location of the forest reserve more accurately, which occupied both the Mandai and Sembawang areas, and is today part of Mandai Wildlife Reserve.29

When the third population census was conducted in 1891, the report featured a map showing the different census districts. A large area in the north is referred to as “Sembawang”, with “Mandai” and “Upper Mandai” as separate districts situated to the west.30

Milestone Markers

In the early days, Singapore lacked prominent landmarks or a proper address system especially in the rural areas. Before the implementation of postal codes, places were identified by milestones, which were tall stone markers labelled with numbers and placed at key locations along roads, a mile apart (about 1.6 km).

First introduced in the 1840s, these milestone markers (about 2 m in height, with about 35 cm exposed above ground) were useful for postal mail delivery, fare calculation when commuting in buses or trishaws, as well as for policing. The General Post Office sited at the former Fullerton Building was designated the “zero point” for measuring distance on the roads.31

An 1898 map produced by the Straits Settlements Forest Department is one of the earliest to feature the milestone markers erected throughout the island. As shown on the map, five milestones from the 10th to 14th miles were placed along Sembawang Road.32

However, maps produced after 1910 show an extra milestone, the 15th mile, added at the end of Sembawang Road. In 1908, the Municipal Commission had embarked on a project to re-measure main roads and reset milestones. The 15th milestone was most likely added at the time.33

By the early 20th century, the 13th to 15th milestones became synonymous with Sembawang, and people began referring to the area as 13th mile, 14th mile and 15th mile.

Sembawang Road

At present, Sembawang Road is a 23-kilometre-long dual carriageway that stretches from the junction of Mandai Road and Upper Thomson Road all the way to Sembawang Park. It is an important arterial road in northern Singapore and, until the 1980s, it was the only main road connecting the area to town.34

When Chinese coolies cleared the forests for plantations, pathways were also cut to facilitate transportation of the produce into the town area. Sembawang Road began as a carriage road. In his 1844 map of the island of Singapore, John Turnbull Thomson had depicted the road as connecting to Bukit Timah Road and extending all the way to the town centre.35 But after his thorough survey of the interior of Singapore in 1848, and also based on other maps from the 1840s, Thomson showed the road as emerging from two Chinese villages at the foot of Sungei Seletar – Yio Chu Kang in the east and Chan Chu Kang in the west – in the 1848 Map of the old Straits or Silat Tambrau and the Creeks to the North of Singapore Island.36

Works to build a new road, most likely in Sembawang, began sometime around March 1849, and was probably supervised by Thomson who oversaw public works at the time. By the middle of the year, the carriage road had extended to the northern coast facing the Johor Strait. The new road that ran between Sungei Sembawang and Sungei Simpang is clearly depicted on an 1849 map by Thomson titled Map of Singapore Island and Its Dependencies.37

News articles from mid-1849 began referring to the new road as “Thomson’s new road”, and subsequently as “Thomson Road”, “Thomson’s Road” and “Thomsons Road”. The name appears slightly later on maps. On an 1851 British chart titled Straits of Singapore, Durian and Rhio, the road is depicted as “Thompsons Road” and on another 1850s Map of the Island of Singapore and Its Dependencies, the road is called “Thomsons Road”.38

By the 1870s, the road was shown as a major road on maps, with newspapers calling the upper half of the road (from the junction of Mandai Road to the sea) “Seletar Road” and the lower half “Thomsons Road”.39

The Straits Times reported in February 1939 that Seletar Road and parts of Thomson Road would be renamed to avoid confusion. “In future [Seletar Road] is to be called Thomson Road as far at the Yio Chu Kang junction, where it will become Upper Thomson Road, and from the Mandai Road junction to the sea it will be called Sembawang Road.”40

By the beginning of the 20th century, the rubber trade had begun to replace the declining pepper and gambier trade. With the opening of the Sembawang Naval Base in 1938, the area underwent a transformation. Instead of bangsal, villages for rubber plantation workers, living quarters for port workers and black-and-white colonial bungalows for senior British military personnel and their families were built, forever changing the demographics and look of the area.

Makeswary Periasamy is a Senior Librarian with the Rare Collections team at the National Library, Singapore. As the maps librarian, she co-curated “Land of Gold and Spices: Early Maps of Southeast Asia and Singapore” exhibition in 2015, and co-authored Visualising Space: Maps of Singapore and the Region (2015).

Makeswary Periasamy is a Senior Librarian with the Rare Collections team at the National Library, Singapore. As the maps librarian, she co-curated “Land of Gold and Spices: Early Maps of Southeast Asia and Singapore” exhibition in 2015, and co-authored Visualising Space: Maps of Singapore and the Region (2015).Notes

-

Sembawang Hot Spring is the only natural hot spring on mainland Singapore. The other is on Pulau Tekong which is not publicly accessible. ↩

-

For various names given to the Johor Strait, see the Infopedia article: Vernon Cornelius-Takahama, “Strait of Johor,” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published April 2018. ↩

-

Based on email conversations with the Singapore Botanic Gardens (SBG), there is not much information or records on the distribution of the Sembawang tree in Singapore, so it is difficult to say where these trees could have been found in the past. The SBG confirms that the tree is a native species of Singapore but nationally extinct. ↩

-

“Mesua singaporiana,” The Wallich Catalogue: Recreating a 19th Century Herbarium, last accessed 17 October 2024, https://wallich.rbge.org.uk/index.php?section=entries&id=4836. ↩

-

H.N. Ridley, “Malay Plant Names,” Journal of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society no. 30 (July 1897): 34, 256. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

In Malay, buah means “fruit” and pokok means “tree” or “shrub”. Kayea ferruginea was first recorded in 1885 in Vietnam by French botanist J.B. Pierre, and has been called Mesua ferruginea since 1969. The tree grows in wet tropical areas and is native to Borneo, Cambodia, Singapore, Malaysia (including Johor), Thailand and Vietnam, and can also be found in the Andaman Islands. See Henry Nicholas Ridley, The Flora of the Malay Peninsula (London: L. Reeve & Co., 1922), 189–90. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 581.9595 RID); “Kayea Ferruginea Pierre,” Royal Botanic Gardens of Kew, last accessed 17 October 2024, https://powo.science.kew.org/results?q=kayea%20ferruginea. In a 1955 newspaper article, it is noted that the tree is also called “Sembawang” in Riau and Johor, while it is called “senawang” in Kedah. See S. “Ramachandra”, “What’s in a Name: Trees Were the Fad in Singapore,” Straits Times, 16 January 1955, 21. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Yen Ching-Hwang, A Social History of the Chinese in Singapore and Malaya 1800–1911 (Singapore: Oxford University Pres, 1986), 120 (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 301.45195105957 YEN); Carl A. Trocki, Prince of Pirates: The Temenggongs and the Development of Johor and Singapore 1784–1885 (Singapore: Singapore University Press, 1979), 92. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 959.5142 TRO) ↩

-

Timothy Pwee, “From Gambier to Pepper: Plantation Agriculture in Singapore,” BiblioAsia 17, no. 1 (April–June 2021): 50–55. ↩

-

Tony O’Dempsey and Chew Ping Ting, “The Freshwater Swamp Forests of Sungei Seletar Catchment: A Status Report,” Proceedings of Nature Society, Singapore’s Conference on “Nature Conservation for a Sustainable Singapore, 16 October 2011, 121, https://www.academia.edu/11820463/the_freshwater_swamp_forests_of_sungei_seletar_catchment_a_status_report. ↩

-

“Mapping Singapore 1819–2014,” in National Library Board, Visualising Space: Maps of Singapore and the Region (Singapore: National Library Board, 2015), 88. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 911.5957 SIN); William Farquhar, Plan of the Island of Singapore Including the New British Settlements and Adjacent Islands, 1822, map. (From National Library Online) ↩

-

William Marsden, Map of the Island of Sumatra Constructed Chiefly from Surveys Taken by Order of the Late Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, 1829, map. (From National Library Online, accession no. B29029422H) ↩

-

Gambier and pepper were usually cultivated together. The more lucrative pepper was seasonal while gambier could be grown throughout the year, which kept the plantation coolies gainfully employed. The waste produced from the processing of gambier also served as fertiliser for pepper vines. ↩

-

Kwek Yan Chong, Hugh T.W. Tan and Richard T. Corlett, “A Checklist of the Total Vascular Plant Flora of Singapore: Native, Naturalised and Cultivated Species,” ResearchGate, January 2009, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/256094053_A_checklist_of_the_total_vascular_plant_flora_of_Singapore_native_naturalised_and_cultivated_species. ↩

-

Coconuts were first planted in 1823 and these flourished mostly along seashores. For more details, see Pwee, “From Gambier to Pepper: Plantation Agriculture in Singapore,” 50–55. ↩

-

Plan of the British Settlement of Singapore by Captain Franklin and Lieut. Jackson in John Crawfurd, Journal of an Embassy from the Governor-General of India to the Courts of Siam and Cochin-China (London: Henry Colburn, 1828), facing page 529. (From National Library Online, accession no. B20116740J); Mok, “Mapping Singapore 1819–2014,” 90. ↩

-

Sketch of the Island of Singapore in Sophia Raffles, Memoir of the Life and Public Services of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, F. R. S. (London: John Murray, 1830). (From National Library Online); Chart of Singapore Strait the Neighbouring Islands and Part of Malay Peninsula drawn by J.B. Tassin in 1836 and printed in J.H. Moor, Notices of the Indian Archipelago, and Adjacent Countries (Singapore, 1837). (From National Library Online, accession no. B03013554J) ↩

-

Carl A. Trocki, “The Origins of the Kangchu System 1740–1860,” Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 49, no. 2 (230) (1976), 132. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Lim Guan Hock, “Gambier and Early Development of Singapore,” in A General History of the Chinese in Singapore, ed. Kwa Chong Guan and Kua Bak Lim (Singapore: Singapore Federation of Chinese Clan Associations: World Scientific, 2019), 38–39, 46, 48–49. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 305.895105957 GEN); John Turnbull Thomson, Letters: J.T. Thomson, vol. 1. (n.p.: n.p., 1847–1853), 50. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RDLKL 526.9092 THO). The 1848 report can be found in this volume. In his report, Thomson does not mention any other settlements along Sungei Sembawang. ↩

-

Thomson, Letters: J. T. Thomson, 52. Thomson states that the Chinese were unwilling to reveal the names of the headmen because they did not speak the “Malayan language” and misconstrued Thomson’s motives. Instead, the names were provided by Thomas Duncan, the Superintendent of Police at the time. ↩

-

John Turnbull Thomson, Map of the Old Straits or Silat Tambrau and the Creeks to the North of Singapore Island, 1848, map. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. HC000870) ↩

-

The kang were usually named after the surname of the headmen, but researcher Lim Guan Hock speculates that Nam To Kang was likely named after a geographical feature. It is also known that the kang had links to Chinese secret societies, with Nam To Kang being affiliated to the Ngee Heng Kongsi. ↩

-

“Untitled,” Straits Times, 15 May 1855, 5. (From NewspaperSG); O’Dempsey and Chew, “The Freshwater Swamp Forests of Sungei Seletar Catchment: A Status Report,” 121, 124–25. ↩

-

Nathaniel Cantley, “Report on the Forests of the Straits Settlements,” in Proceedings of the Legislative Council of the Straits Settlements for the Year 1883 (Singapore: Government Printing Office, 1883). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RRARE 328.5957 SSLCPL; accession no. B20048240I) ↩

-

H.M. Burkill, “The Botanic Gardens and Conservation in Malaya,” The Gardens’ Bulletin Singapore 17 (1958): 201–02, https://www.nparks.gov.sg/sbg/research/publications/gardens’-bulletin-singapore/-/media/sbg/gardens-bulletin/4-4-17-2-13-y1959-v17p2-gbs-pg-201.pdf; Lim Tin Seng, “Saving Singapore’s Forests,” in National Library Board, Stories From the Stacks: Selections From the Rare Materials Collection National Library (Singapore: National Library Board, 2020), 93. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 016.95957 SIN-[LIB]) ↩

-

“Gang Robbery,” Straits Times, 3 March 1903, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

For further information on the villages, see the manuscript notes of Lee Kip Lin in his report, Villages in the Rural District Areas [circa 1960s]. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RDLKL 307.72095957 VIL) ↩

-

“Cong lan tu gang dao shuichí cun,” 從爛土港到水池村 [From Lang Tu Port to Pool Village], 星洲日报Sin Chew Jit Poh, 11 November 1968, 20. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Survey Department Singapore, Map of the Island of Singapore and Its Dependencies, 1873, map. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. GM000297_1) ↩

-

The National Archives, United Kingdom, Map of the Island of Singapore, 1886, map. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. D2016_000204) ↩

-

Map no. II – Map of the Island of Singapore and Its Dependencies: Shewing Census Divisions – 1891 in E.M. Mereweather, Report on the Census of the Straits Settlements, Taken on the 5th April 1891 (Singapore: Printed at the Government Printing Office, 1892). (From National Library Online, accession no. B18976509A) ↩

-

National Archives of Singapore, “Singapore, Mileages Along Roads, 1936,” 11 December 2015, https://corporate.nas.gov.sg/media/collections-and-research/singapore-mileages/; Melody Zaccheus, “In Singapore, All Roads Lead to the General Post Office,” Straits Times, 22 June 2015, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Map of the Island of Singapore and Its Dependencies, Executed by the Colonial Engineer and Surveyor General of the Straits Settlements in 1898, to Accompany Report on the Forest Administration in the Straits Settlements by H.C. Hill Esquire, Conservator of Forests. (From National Library, Singapore, accession no. B20124024D) ↩

-

Royal Geographical Society, London, Map of the Island of Singapore and Its Dependencies, 1911, 1912, map. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. D2018_000214_RGS); “Municipal Commission,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 6 June 1908, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Thulaja Naidu Ratnala, “Sembawang Road,” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published September 2020. ↩

-

John Turnbull Thomson and John Arrowsmith, Singapore Island Surveyed and Drawn By J.T. Thomson, Government Surveyor, Singapore 20th Dec 1844, 1844, map. (From National Library Online). ↩

-

Lim, “Gambier and Early Development of Singapore,” 49; Thomson, Map of the Old Straits or Silat Tambrau and the Creeks to the North of Singapore Island. ↩

-

“Page 1 Advertisements Column 3: Disbursements,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 1 March 1849, 1. (From NewspaperSG); John Turnbull Thomson, Map of Singapore Island and Its Dependencies, 1849, map. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. SP007229) ↩

-

See for example, “Gang Robbery and Murder,” Straits Times, 26 June 1849, 4; “Local”, Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 3 May 1850, 2; “Page 1 Advertisements Column 2,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser , 12 February 1857, 1. (From NewspaperSG). For the maps, see Great Britain Hydrographic Office, Straits of Singapore, Durian and Rhio (London: Hydrographic Office of Admiralty, 1851). (From National Library, Singapore, accession no. B20124033D); The National Archives, United Kingdom, Map of the Island of Singapore and Its Dependencies, c. 1854, map. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. SP006818) ↩

-

“Monday 1st November,” Straits Times, 6 November 1875, 4; “The Municipality,” Straits Times Overland Journal, 12 April 1879, 3; “New Names for Roads,” Straits Times, 14 February 1939, 14. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“New Names for Roads.” The name “Seletar Road” originated from the Malay word Seletar, which was also used for Sungei Seletar (Seletar River) and the Orang Seletar living along the river. It was most likely a name used by the locals to refer to the new road. ↩