In Good Hands: The Calligraphy of Ustaz Syed Abdul Rahman Al-Attas

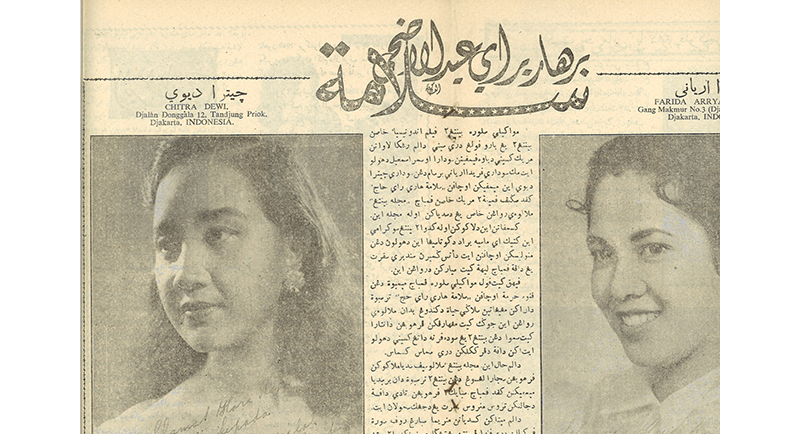

The master calligrapher’s artworks not only adorn physical spaces but are also found in Malay print publications.

By Nurul Wahidah Mohd Tambee

If you visit Sultan Mosque, you are likely to hear stories about its history and architecture, and especially how, as part of fundraising efforts, glass bottles line the base of each dome in neat rows as a contribution from the people in the community in the late 1920s.1 This was a mark of the hands of people who gave, despite not having much to give. Hands made this building, hands have kept it together, and hands will keep it going.

But if you enter Sultan Mosque and walk up to the mihrab (the pulpit or prayer niche that indicates the direction of Mecca), you will notice the work of another hand. Above the mihrab, right at the top of the middle panel is the Arabic word “Allah”, written in the Thuluth calligraphy style noted for its curvilinear features. Encircling the word is the text from “Surah Al-Ikhlas”, the 112th chapter of the Qur’an. The name and salutations for Prophet Muhammad flank the left and right sides of this circle. Below the circle is verse 18 of “Surah At-Tawbah”, the 9th chapter of the Qur’an. Both the text and verse are written in Thuluth Jali, a decorative form of Thuluth calligraphy used in Islamic architecture.

If you squint a little bit more, you will see on the bottom right corner of the central panel the Arabic words “Katabahu Abdul Rahman Al-Attas” (Written by Abdul Rahman Al-Attas) in Diwani calligraphy, a cursive style which traces its history to the 16th-century Ottoman court. On the bottom left corner is the date “6 Rabi’ulawal Sanat 1368” in the Hijri (Islamic) calendar, or 5 January 1949, indicating the completion date of the calligraphy. The man behind the calligraphy is Abdul Rahman Al-Attas.

A Prolific Calligrapher

Abdul Rahman Al-Attas, or Al-Ustaz Syed Abdul Rahman bin Hassan Al-Attas Al-Azhari, was a prolific calligrapher who was born in Johor Bahru in 1898. Not much is known about his life beyond that he studied calligraphy in Cairo, Egypt, first at Madrasah Tahsin Al-Khuttut and subsequently at Al-Azhar University, earning him the epithet “Al-Azhari”.2 Indeed, the Egyptian influence would pervade the calligraphic works that he would later produce.

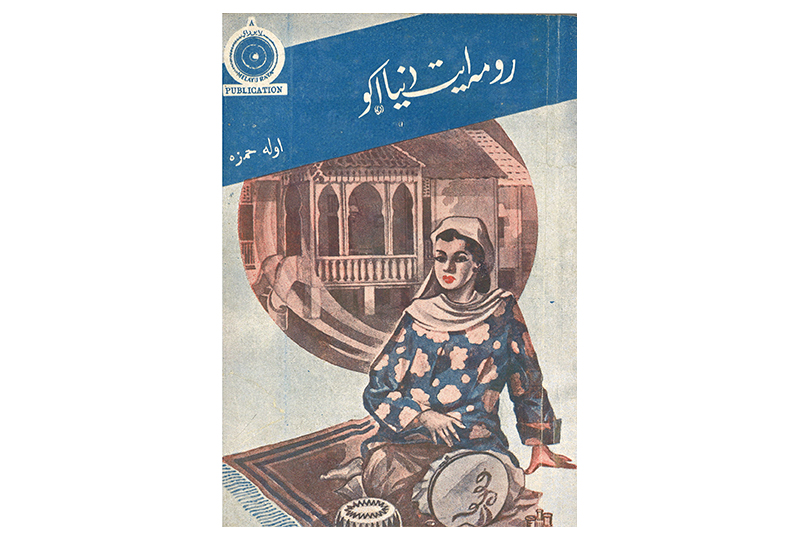

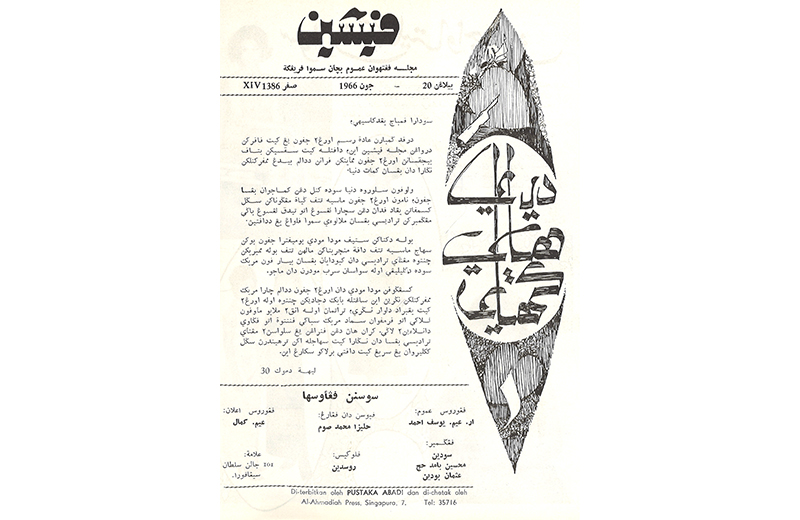

Although the more enduring calligraphy artworks by Abdul Rahman Al-Attas still exist today in the form of Qur’anic verses in Sultan Mosque, as well as mosques in other parts of Southeast Asia, his most quantitatively significant contributions can be found in more utilitarian and literary spaces. These are the Jawi titles and headers of Malay print materials, i.e., magazines, books and other ephemera produced mainly in Malaya from the 1950s to 1960s.

To understand why his Jawi calligraphy endured and why it was a significant marker of printed Malay materials in the period before Singapore’s separation from Malaysia and independence, we need to understand the means of producing these materials.

Jawi Calligraphy in Malay Print Materials

The romanisation of Malay print materials only came about in the latter half of the 20th century, after World War II. Before the romanisation of the Malay language, the predominant way of conveying knowledge, information and stories in print was in Jawi – a means of visually representing or encoding the Malay language using a modified Arabic script.3

Although book printing and production in the Western world changed with the arrival of the printing press and the moveable type, much of the world that relied on Arabic characters in their means of communication – such as Ottoman Turkey, Northwestern Africa and India – found the moveable type restrictive and stilted; it could not quite capture the fluidity of the handwritten Arabic script.

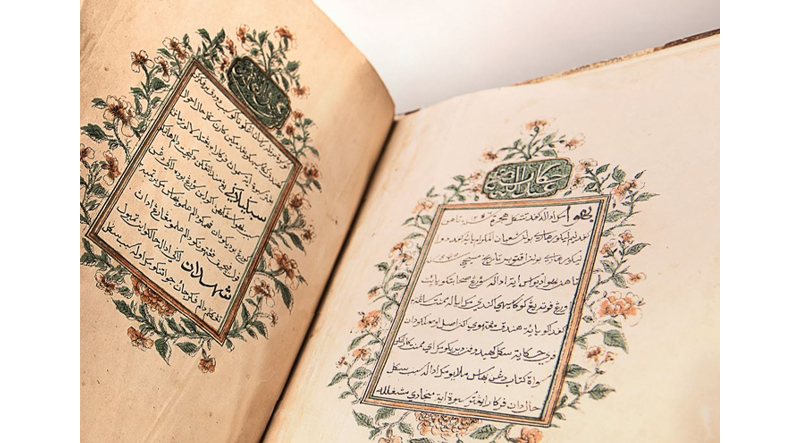

It was not until the invention of lithography that the reproduction of texts in Arabic characters flourished since lithography was able to reproduce handwritten text. Handwritten Arabic made for much easier reading and was visually more acceptable to the readerly eye than Arabic typography.4 A notable example of a lithographed text in Singapore is the famous Hikayat Abdullah (Stories of Abdullah) by the Malay teacher and scribe Abdullah Abdul Kadir (better known as Munsyi Abdullah) lithographed by the Mission Press in 1849.5

Nevertheless, many of the printing presses in Southeast Asia eventually adopted the moveable type due to the speed, ease and volume of reproduction. The bulk of Jawi texts, books, newspapers and periodicals eventually began to be printed using compositions of Arabic characters in a moveable type.6

However, many Malay books and magazines still preferred to use Jawi calligraphy for their titles and masthead on the cover instead of the romanised script for aesthetic reasons. These illustrated words would require a reproduction – via lithography, other methods of relief printing, customised plates or customised metal type – of a skilled calligrapher’s work. One would assume that it was because calligraphy offered these printed Malay books and magazines what the moveable type could not provide – aesthetic variety, style and flexibility. And this was where the handwritten work of Abdul Rahman Al-Attas came in.

A Master of All Styles

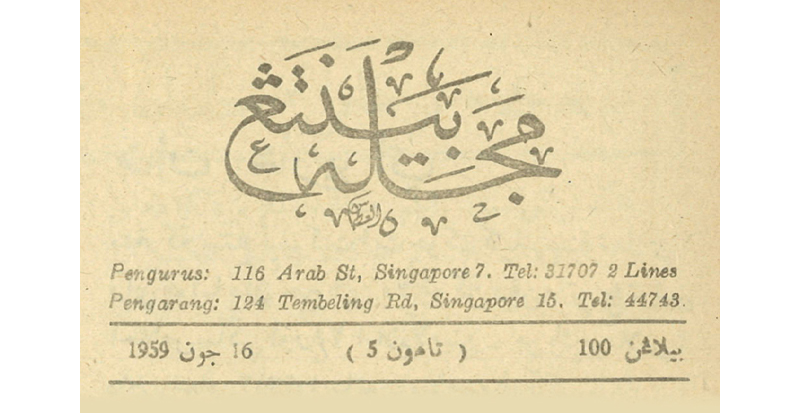

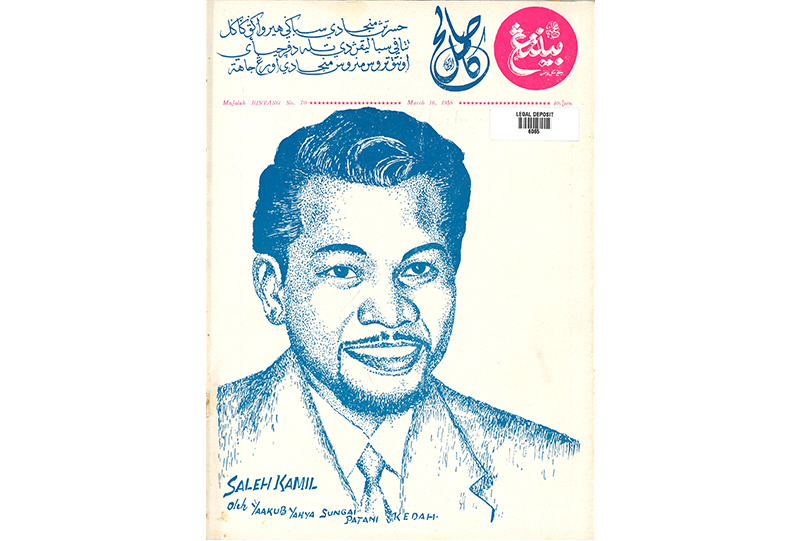

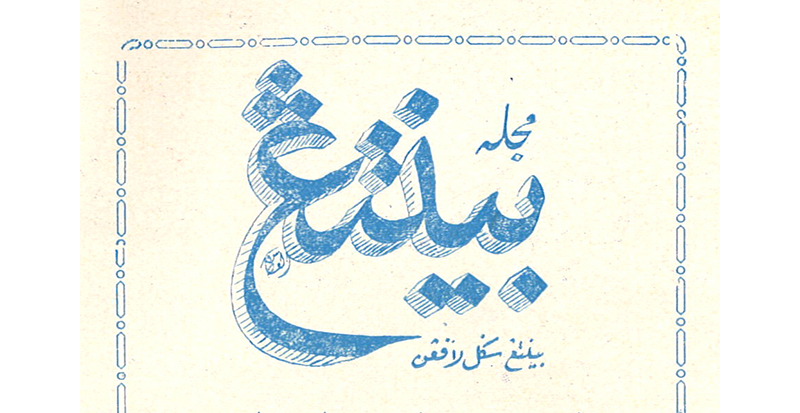

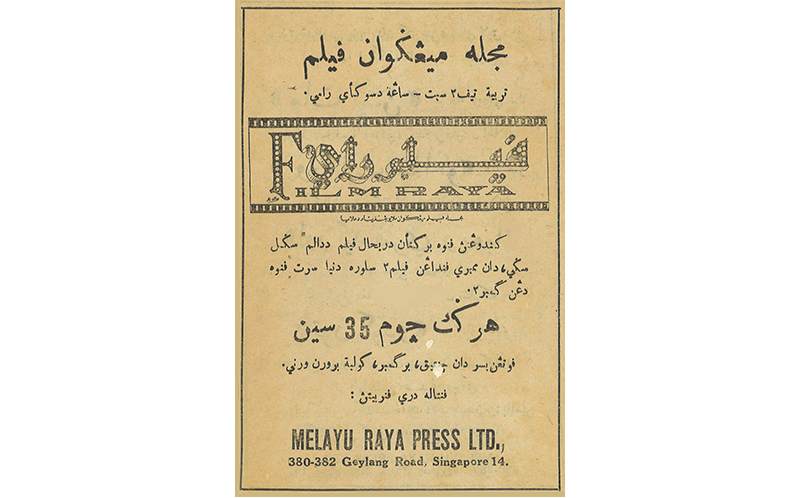

A unique feature of Arabic calligraphy, and thus Jawi calligraphy – which lends itself to the aesthetics of Malay print materials – is its ability for words and sentences to be compressed in a prescribed space by way of artfully stacking letters. Abdul Rahman Al-Attas used this aspect of calligraphy to his advantage such as when creating variations of the title of entertainment magazine Majalah Bintang on the cover and first page.

Whether it was the more compact and sturdy Riq’ah, the rounded curls of Diwani, the romantic Nasta’liq, or the precision and perfection of Naskh and Thuluth, Abdul Rahman Al-Attas’s calligraphic proficiency was well demonstrated on the page. Because he had learnt these styles while studying in Egypt, his calligraphy carries a distinctive Egyptian influence that is slightly different from the Ottoman Turkish or Baghdadi variants of the same style.7

Calligraphy in Singapore and Southeast Asia

Other than Sultan Mosque, Abdul Rahman Al-Attas’s calligraphy also adorns the shrine of Muslim saint Habib Noh bin Muhammad Al-Habsyi on Palmer Road in Tanjong Pagar.8 Across Southeast Asia, Abdul Rahman Al-Attas’s calligraphy can be found in places such as the tomb of Sultan Zainal Abidin in Kuala Terengganu, the Malaysian parliament building and Masjid Jame’ in Bandar Seri Begawan. His works are also preserved in collections owned by the Sultan of Johor, the Museum of Asian Art in the University of Malaya as well as the National University of Malaysia.9

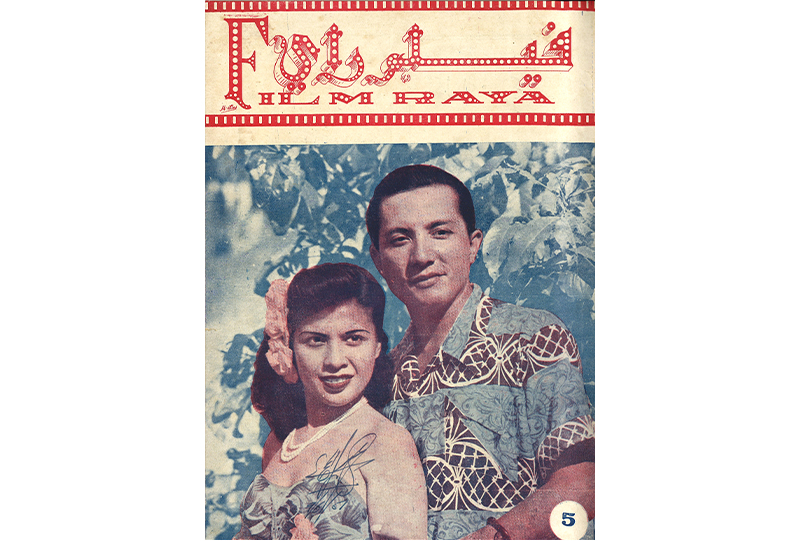

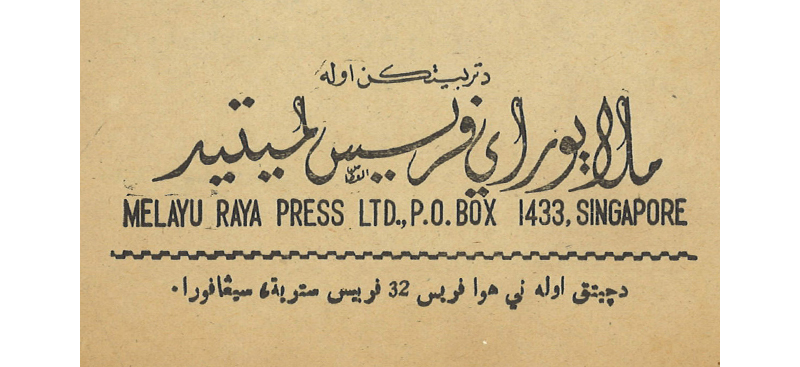

Abdul Rahman Al-Attas also designed the titles and mastheads for a number of Malay print publications. Easily identified by his signature, his calligraphy is found in the works published by various Malay publishing houses in Singapore in the 1950s and 1960s, including Qalam Press, Melayu Raya Press, Pustaka H.M. Ali and Matba’ah Sulaiman Mar’ie. For instance, for the title of Film Raya, a magazine published bv Melayu Raya Press, his signature is found just beneath the letter “F”.

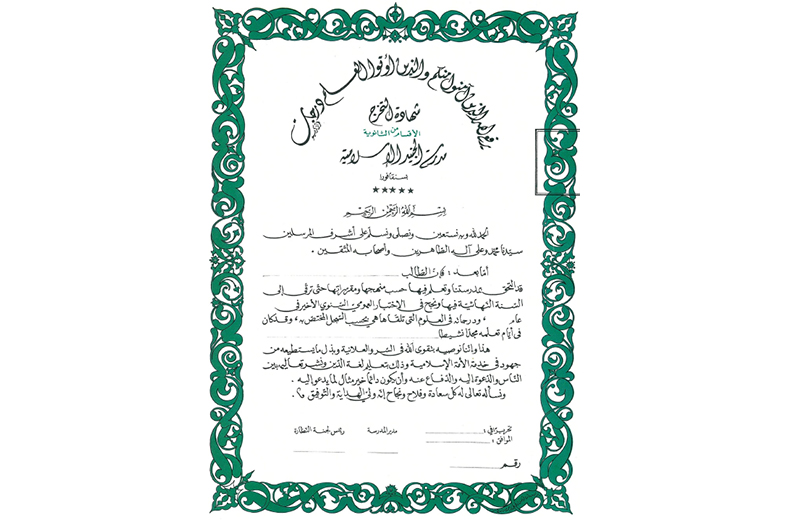

The master calligrapher’s penmanship also decorates the graduation certificate of Madrasah Aljunied Al-Islamiah. Neatly written in Jawi amid the swirling green vegetal border at the bottom right corner of the certificate is the text “Ditulis dan dilukis oleh Abdul Rahman Hassan Al-Attas” (Written and drawn by Abdul Rahman Hassan Al-Attas), which indicates that he was responsible for both the calligraphy and the design of the decorative border.

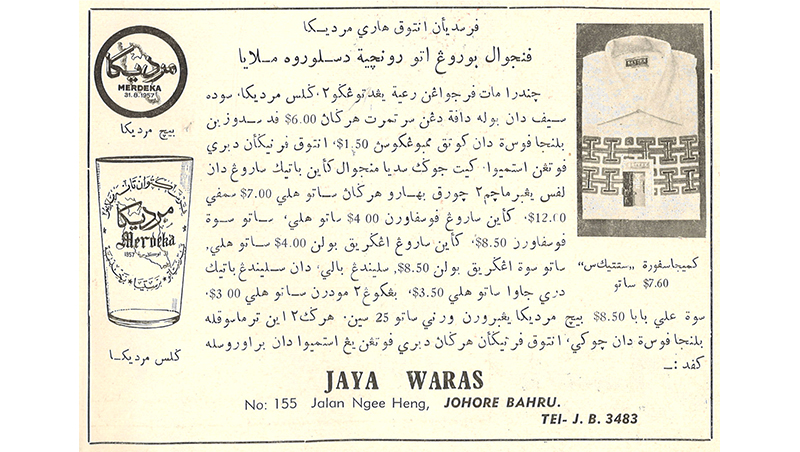

Abdul Rahman Al-Attas’s calligraphy is not just limited to buildings and print publications. His calligraphy can also be found in a series of commemorative glass cups produced in 1957 after the Federation of Malaya gained independence from the British. Printed on the cups is “Merdeka” written in Jawi, and just below the Arabic letter “م” (mim) is his signature.

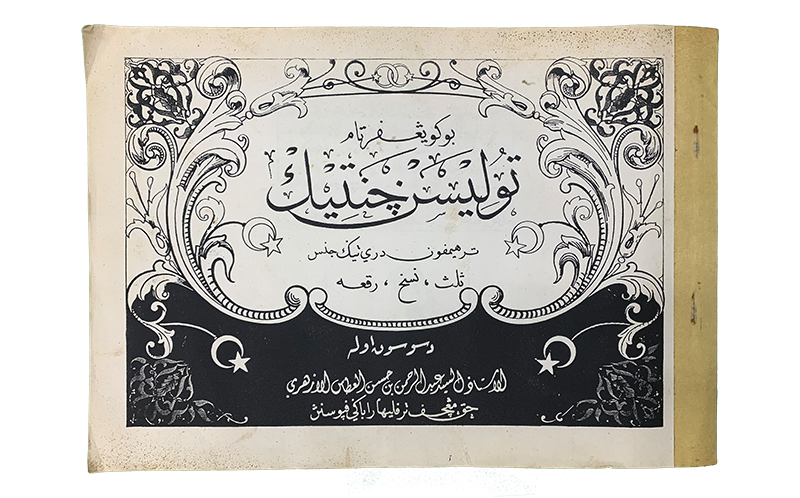

Abdul Rahman Al-Attas also produced his own calligraphy reference book, Tulisan Cantik. (Unfortunately, the date and place of publication are unknown.) The publication showcases his handwriting in the Thuluth, Naskh and Riq’ah styles, a section on how calligraphers may create and prepare their own calligraphy pen for writing, and instructions such as writing in a well-lit place.

Other Calligraphers and Calligraphy Styles

According to Ustaz Syed Agil Othman Al-Yahya, the former principal of Madrasah Aljunied Al-Islamiah in Singapore (who is himself a prolific calligrapher), some of the other calligraphers who were active in Singapore in the 1940s up to the 1990s include Al Ustaz Al-Fadhil As-Sayyid Abu Bakar bin Abdul Qadir Al-Yahya, Al-Ustaz Al-Fadhil Abdur Rashid Junied, Al-Ustaz Al-Fadhil Mustajab Che’ Onn, Al-Ustaz Al-Fadhil Muhammad Tarmidzi Hj Hassan, Al-Ustaz Al-Fadhil Ameen Muslim and Al-Ustaz Al-Fadhil Mahmood Abdul Majid.10

While perusing Jawi print materials in the collections of the National Library, I came across the works of other calligraphers that bear their signatures. However, for the moment, the identity of these calligraphers remains a mystery to me until more research is done.

Decoding Jawi Texts

While Arabic and Jawi calligraphy may have limited use in the Malay print and publishing industry in the 21st century, Jawi texts – such as handwritten manuscripts, lithographed materials and print publications – should nonetheless be studied and referenced as a point of access to the wealth of knowledge and perspectives across the Malay Archipelago.

There have been efforts to create software that can convert Jawi to romanised Malay. But most of these focus on Jawi printed text reproduced via moveable type and not so much on handwritten Jawi or Jawi calligraphy, where the different ways of depicting characters in various calligraphy styles and the idiosyncrasies of handwriting pose a challenge.

Also, the many spelling variations of certain words11 present a problem to those looking to use more precise software for the transliteration of Jawi texts. Added to that, deciphering Jawi calligraphy – especially when it is more complex and artistic – is sometimes difficult even to a proficient Jawi reader. Perhaps with time and advancements in technology, the right software will be able to decode intricate works of Jawi calligraphy. What is at stake is not only works in Malay. That same technology can be used for knowledge recorded in Arwi or Arabu Tamil – a dialect of the Tamil language written using Arabic characters – to make it accessible to the wider audience as well.

Nurul Wahidah Mohd Tambee is a Manager/Librarian at Resource Discovery, National Library Board. She works closely with Malay- language materials.

Notes

-

Ten Leu-Jiun, “The Invention of a Tradition: Indo-Saracenic Domes on Mosques in Singapore,” BiblioAsia 9, no. 1 (April–June 2013): 16–23; National Heritage Board, “Sultan Mosque,” Roots, last updated 1 July 2022, https://www.roots.gov.sg/places/places-landing/Places/national-monuments/sultan-mosque. ↩

-

Faridah Che Husain, “Seni Kaligrafi Islam Di Malaysia Sebagai Pencetus Tamadun Melayu Islam” (Master’s thesis, Universiti Malaya, 2000), 65–66, http://ir.upm.edu.my/find/Record/u502336. ↩

-

Jawi includes additional characters that do not exist in the Arabic alphabet to encompass the “ny”, “ng”, “p”, “v” and “ch” sounds present in the Malay language. ↩

-

Ian Proudfoot, “Mass Producing Houri’s Moles or Aesthetics and Choice of Technology in Early Muslim Book Printing,” in Islam: Essays on Scripture, Thought and Society. A Festschrift in Honour of Anthony H. Johns, ed. Peter G. Riddell and Tony Street (New York: Brill, 1997), 170–77. ↩

-

Abdullah Abdul Kadir, Munshi, Hikayat Abdullah (Singapore: Mission Press, 1849). (From National Library Online); Bernice Ang, Siti Harizah Abu Bakar and Noorashikin Zulkifli, “Writing to Print: The Shifting Roles of Malay Scribes in the 19th Century,” BiblioAsia 9, no. 1 (April–June 2013): 40–44; Gracie Lee, “The Early History of Printing in Singapore,” BiblioAsia 19, no. 3 (October–December 2023): 30–37. ↩

-

A Jawi moveable type has additional characters that do not exist in the Arabic alphabet to encompass the “ny”, “ng”, “p”, “v” and “ch” sounds in the Malay language. ↩

-

Hasan Abu Afash, “Tamyīzul Furuqāti al-Asāsiyah fī Asālībi Katābati al-Khaṭ al-Dīwānī” تمييز الفروقات الأساسية في أساليب كتابة الخط الديواني [Distinguishing the Basic Differences in the Methods of Writing Diwani Calligraphy], Hiba Studio, 1 January 2014, https://hibastudio.com/diwany-differance/. ↩

-

Bonny Tan, “Habib Noh,” in Singapore Infopedia, National Library Board Singapore. Article published 19 August 2016; Syed Agil Othman Al-Yahya, Arabic Calligraphy (Singapore: S. Agil Othman Alyahya, 2022), 3. (From PublicationSG) ↩

-

Faridah Che Husain, “Seni Kaligrafi Islam di Malaysia Sebagai Pencetus Tamadun Melayu Islam,” 65–66. ↩

-

Syed Agil Othman Al-Yahya, Arabic Calligraphy, 21–22. ↩

-

Dr Hirman Khamis, a Malay-language teacher and an expert in Jawi, once shared that he had encountered almost 13 ways in which the word for “humans”, i.e., “manusia”, was spelt in Jawi orthography. ↩