Legal Deposit Legislation in Singapore

The legal deposit function in Singapore can be traced back to an 1835 law enacted in India to control and regulate the flow of information.

By Makeswary Periasamy

National libraries worldwide serve as custodians of their nations’ published heritage, collecting and preserving materials for future generations. These collections represent the cultural and literary memory of the respective countries. In early post-independent Singapore, the library was hailed as a symbol of nationhood,1 with legal deposit becoming a crucial tool for building and maintaining its collections.

Originating in France in 1537,2 legal deposit is a legislation enacted by a country to ensure copies of every local publication are deposited with one or more designated institutions. Similar legislation enacted in Great Britain in the mid-17th century was extended to its colonies and territories in the early 19th century.3 While initially conceived to control the printing press and to censor heretical ideas, legal deposit legislation evolved into a tool for registering copyright and intellectual property ownership, ultimately becoming an expedient method for collecting and preserving local literary heritage.

Early Legislations

Singapore’s legal deposit system traces its origins to the Book Registration Ordinance No. XV of 1886 in the Straits Settlements (comprising Melaka, Penang and Singapore). This ordinance stemmed from two earlier legislations from colonial India, enacted in 1835 and 1867, designed to regulate the press and control information flow. It also emerged from 19th-century legislative changes in the United Kingdom (UK) and lobbying efforts by the British Museum and other UK institutions seeking deposits of works published throughout the British Empire, including the Straits Settlements.

The Indian Act No. XI of 1835 first mandated that printers and publishers must declare their “periodical work” before a magistrate and file the records with the court. This act introduced fundamental principles, including the mandatory printing of names and places of printing/publication clearly on all works, with penalties for non-compliance.4

The UK’s International Copyright Act of 1838 introduced requirements for registering all new publications at Stationers’ Hall in London, with a copy to be deposited in the British Museum Library. The act was also extended to the British Dominions and required detailed registers to be maintained. Both registration and the certificate of proof incurred charges.5

Subsequent amendments in 1839 and 1842 mandated delivery of new works to the British Museum within one month of publication or offer for sale, with the 1842 act encompassing colonial publications too. When the museum encountered difficulties obtaining works from both domestic and overseas publishers, an 1878 government report recommended combining both the registration and deposit functions within the museum while colonial publications were purchased.6

The Indian Act No. XXV of 1867 superseded the 1835 act and took charge of press regulation. It also expanded on the regulations requiring three copies of every book printed or lithographed in British India to be preserved and registered.7 Though not directly applicable to the Straits Settlements, this act established the foundation for Singapore’s legal deposit regulations.

The 1867 Indian Act maintained the printing press restrictions of 1835, requiring all publications to clearly display the printer’s name, publisher’s details and place of publication. The act broadly defined “book” to include printed books, serials, pamphlets, sheet music and maps. Publishers had to submit three “best copies” of each publication, including any subsequent editions, to a designated local government official (as notified in the gazette) within one month. Notably, the 1867 act required officials to pay for deposit copies intended for public sale and, more importantly, maintain a catalogue specifically titled Catalogue of Books Printed in British India, which shall contain a “memorandum of every book” deposited. Following the 1838 Copyright Act, registering a deposit copy in the catalogue incurred a nominal fee.8

These catalogues enabled the British Museum and other institutions to track and buy publications from British colonies when traditional deposit methods proved unsuccessful.9

The British Museum’s collecting efforts faced challenges with the UK’s International Copyright Act of 1886 which exempted British possessions from deposit requirements in the UK. Fortunately, the Colonial Office in London directed all colonial governors to implement a book registration system mirroring the successful model established in Ceylon (Sri Lanka) the previous year, including sending copies directly to the British Museum.10 Most colonies agreed and enacted corresponding laws.

Book Registration Ordinance of 1886

The Book Registration Ordinance, implemented on 1 January 1887, required three copies of every Straits Settlements publication to be deposited with Singapore’s Colonial Secretary’s Office. One deposited copy and two copies of the memoranda of books were subsequently sent to the British Museum Library.11

Similar to the 1867 Indian Act, the 1886 ordinance broadly defined “book” to include “every volume, or part of division of a volume, and pamphlet, in any language, and every sheet of music, map, chart or plan separately printed or lithographed”.12 Publication details were recorded in an official catalogue, published quarterly in the government gazette. If printers did not comply, they could be fined up to $25.

Though not officially designated as the local depository, the Raffles Library (National Library’s predecessor) received one of the deposited copies.13 This arrangement and the challenge in managing the collection was documented by Librarian G.D. Haviland in 1893. He wrote: “Since 1886, publications have been forwarded to the Library under the Book Registration Ordinance; these have never been arranged at all; this year a small room has been kept especially for them, but they have not yet been sorted sufficiently to make them available for reference.”14

The Raffles Library and Museum operated as a unified institution initially situated within the Raffles Institution building. The relocation to its new premises in 1887 (now the National Museum of Singapore) was prolonged, primarily due to the substantial expansion of its collection following the implementation of the 1886 ordinance.15

The Printers and Publishers Ordinance

In 1920, the Legislative Council of Singapore passed new legislation that expanded the law governing newspapers, books, documents and printing presses.16 Known as Ordinance No. 2 (Printers and Publishers), it consolidated both the Indian Act No. XI of 1835 and the Book Registration Ordinance No. XV of 1886.

The Colonial Secretary’s Office maintained its role in receiving and registering new Singapore publications and recorded them for the quarterly gazette notification. Since January 1931, Chinese books published in Singapore were delivered to the Chinese Protectorate,17 who redirected them to the Colonial Secretary.18 The legislation underwent several amendments before its 1936 revision as the Printers and Publishers Ordinance (Chapter 209).19

The Japanese Occupation (1942–45) temporarily disrupted the deposit system. Colonial staff members, Edred J. H. Corner and William Birtwistle, documented rescue operations to safeguard existing collections within civil service departments, including the Colonial Secretary’s Office. Normal operations resumed after the war.20

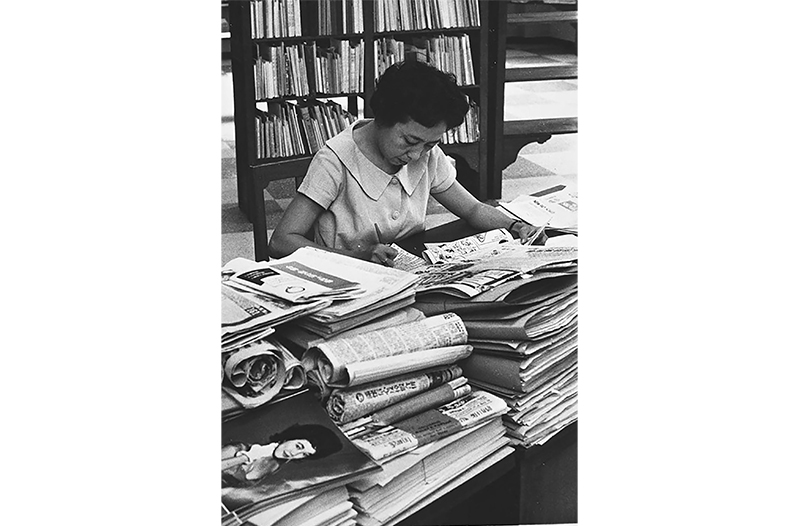

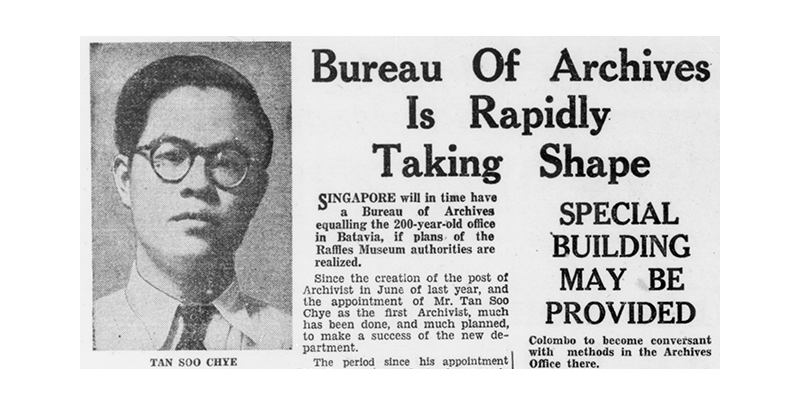

A significant change occurred in 1948 when the Raffles Library and Museum assumed responsibility for administering the Printers and Publishers Ordinance, becoming the official depository institution. This function came under the charge of the Archivist, a position created in 1938.21

Tan Soo Chye, appointed as the first Archivist, began reporting the annual statistics of newly registered books under the ordinance from 1950 onwards. His 1951 report for the Raffles Library and Museum noted that these figures excluded newspapers and periodicals, while Chinese books remained under the purview of the Chinese Secretariat (formerly Chinese Protectorate). He also noted the continued practice of sending deposit copies to the British Museum Library.22

A significant reorganisation occurred in 1955 when the management of government archives, microfilming of records and the legal deposit function were transferred from the Archivist to the Librarian. This shift added to the existing “book and information services” of the Raffles Library.23 The transfer was partly necessitated by Tan’s departure to the Department of Customs and Excise in December 1953, leaving the Archivist position vacant until 1967.24

The 1955 amendments to the ordinance, now known as the Printers and Publishers Ordinance (Chapter 196), formally authorised the Raffles Library to collect and preserve local publications via deposit.25 That same year marked the separation of library and museum functions, with the appointment of a dedicated director for the Raffles Library.26 The fine for non-compliance also increased from $25 to $50.

The Raffles National Library Ordinance of 1957 ushered in a milestone in the history of the National Library. In 1958, Raffles Library was renamed Raffles National Library and became a free public library. This legislation established the library as “the only authority in the Colony providing a library service for the general public” with government financial support. More importantly, the ordinance empowered the library and its director to collect and preserve all publications printed in Singapore through deposit.

Prior to 1955, the director of the Raffles Museum held responsibility for library and archives functions, including the mandate to receive publications on deposit. The 1957 ordinance transferred these depository functions and the archives legally to the Raffles National Library. Subsequently, under the Raffles National Library (Change of Name) Ordinance in 1960, the institution was renamed the National Library.27

In 1967, the National Archives and Records Centre Act was enacted, leading to the separation of library and archives functions. The National Archives and Records Centre was established in 1968 while an amendment to the National Library Act in 1968 reinforced the library’s functions and services, including its authority “to collect and receive all books required to be deposited in the National Library under the provisions of the Printers and Publishers Ordinance and to preserve such books”.28

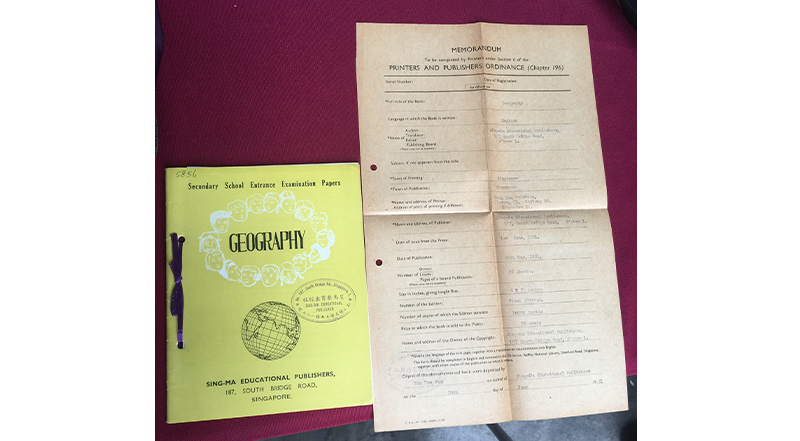

The Printers and Publishers Ordinance underwent several amendments in the 1950s and 1960s. The 1960 amendment mandated that the publisher (previously it was the printer) must deposit six copies (instead of the earlier three copies) of a work published and printed in Singapore to the National Library. The penalty for non-delivery of books by the publisher increased from $50 to $500, which became $1,000 and $5,000 in 1968 and 1996 respectively. Subsequently, the number of deposit copies was reduced to five under the Printers and Publishers (Amendment) Act of 1967.29 Revisions were made to the act in 1970 and again in 1985.

Out of the five copies deposited with the National Library, two copies would be preserved in the library while “the remaining copies shall be disposed of as the Director of the National Library thinks fit”.30

One of the copies retained by the library was preserved in the Publishers and Printers Act collection (later called the Legal Deposit collection and now PublicationSG), while the other was catalogued and kept in the reference section of the National Library. These reference copies are now part of the Singapore and Southeast Asia Collection at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library. The remaining three copies were given to academic libraries and the Ministry of Culture, or sent to the public libraries as loan copies.

Catalogues and Bibliographies

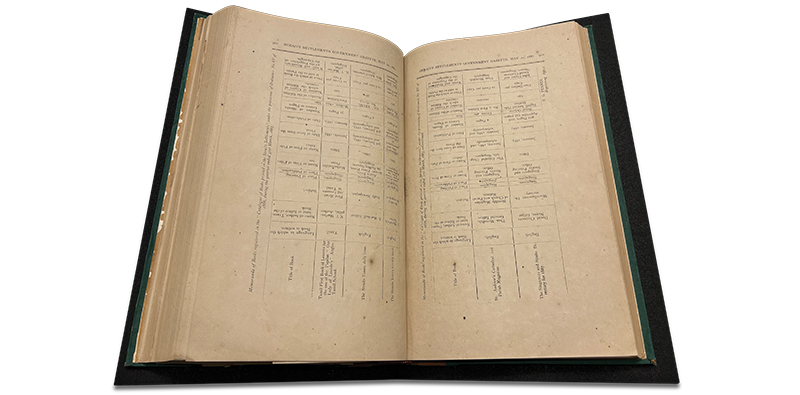

Like the 1867 Indian Act, the 1886 Book Registration Ordinance required the officer registering the deposit copy to maintain a catalogue of books containing all the essential details, known as memorandum, that would be published in the government gazette every quarter. The Colonial Secretary’s Office served as the local depository and an officer there was assigned to register the deposited copies and compile the catalogue.

In Singapore, the very first catalogue of books was published in the 20 May 1887 issue of the gazette for the quarter ending 31 March 1887 with the title Memoranda of Books Registered in the Catalogue of Books Printed in the Straits Settlements Under the Provisions of Ordinance No. XV of 1886.31 The catalogue listed five publications printed in Singapore: a school textbook in Tamil, the weekly and daily issues of the Straits Times, the magazine of St Andrew’s Cathedral and the Singapore & Straits Directory of 1887. The memoranda of books continued to be published in the gazette until April 1995 when the National Library Board Act came into effect.

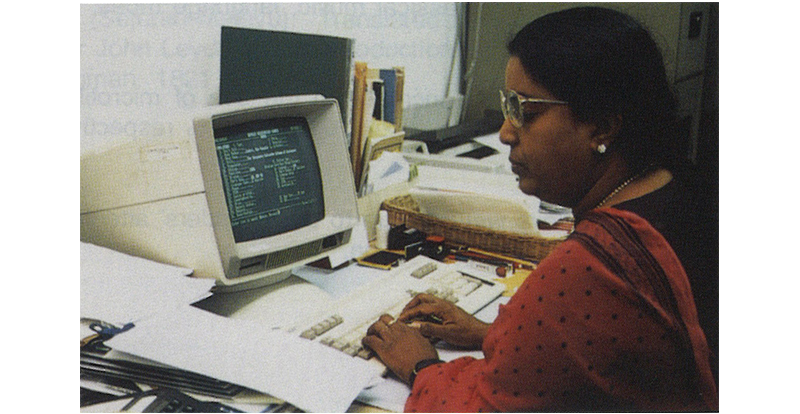

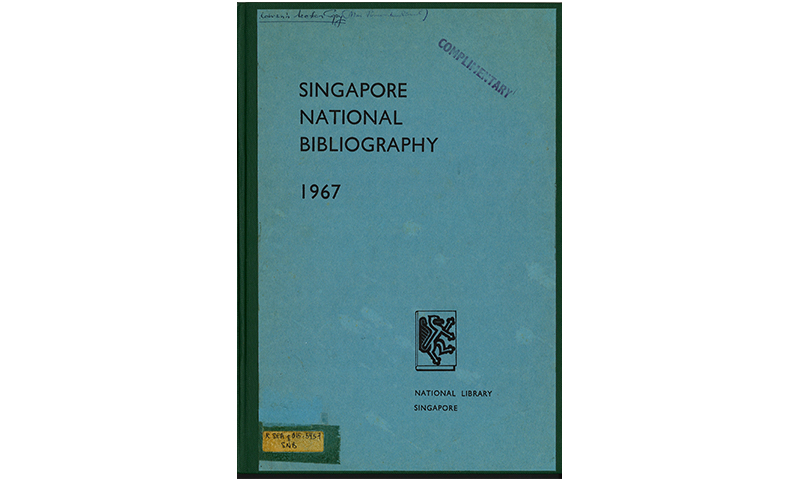

Since 1969, the National Library has been compiling the annual Singapore National Bibliography (SNB) which contains local titles deposited with the library under the Printers and Publishers Ordinance. The compilation of current and historical bibliographies was laid out as a statutory function of a national library within the 1957 Raffles National Library Ordinance.

The first issue of the SNB, featuring publications printed in 1967, was released in August 1969 and sold to the public at $3.32 Over the years, the SNB was expanded to include titles received through donations and purchases as well as electronic publications. It was produced in CD-ROM format from 1993, as a DVD from 2009 and as an online bibliography from 2011. The SNB was decommissioned after the launch of PublicationSG in October 2015, an online catalogue that made publicly available the more than one million legal deposit titles.

New Legislations

In 1995, both the 1985 revised National Library Act and Printers and Publishers Act were subsumed under the National Library Board Act (No. 5 of 1995), establishing the National Library Board (NLB) as the custodian of Singapore’s published heritage. All works that are published or produced in Singapore are required to be deposited with the National Library Singapore within four weeks from the date of publication under Section 10 of the NLB Act.

The number of copies to be deposited by the publisher was reduced to two, and both copies were retained by the National Library. The NLB Act also mandated that only works published and distributed, not printed, in Singapore need to be deposited. Over the years, with the increasing popularity of electronic and online publishing, the act was updated in 2018 to include digital content.33

Over the last 190 years, legal deposit in Singapore has evolved from legislation enacted in India in 1835 – to control and censor printing – into an important tool by which the National Library has been able to comprehensively collect and preserve all works published in Singapore for present and future generations. Both the memoranda of books and the SNB provide a record of Singapore’s publishing activities since the late 19th century and are important sources of information documenting Singapore’s published heritage.

Makeswary Periasamy is a Senior Librarian with the Rare Collections team at the National Library Singapore. As the librarian in charge of maps, she co-curated Land of Gold and Spices: Early Maps of Southeast Asia and Singapore in 2015, and co-authored Visualising Space: Maps of Singapore and the Region (2015).

Makeswary Periasamy is a Senior Librarian with the Rare Collections team at the National Library Singapore. As the librarian in charge of maps, she co-curated Land of Gold and Spices: Early Maps of Southeast Asia and Singapore in 2015, and co-authored Visualising Space: Maps of Singapore and the Region (2015). Notes

-

K.K. Seet, A Place for the People (Singapore: Times Books International, 1983), 112. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 027.55957 SEE-[LIB]) ↩

-

The first legal deposit system was established in France by King Francis I who signed the Ordonnance de Montpellier on 28 December 1537, requiring printers and booksellers to deposit a copy of every printed book with the Royal Library. ↩

-

Patricia Lim Pui Huen, Marion Southerwood and Katherine Hui, Singapore, Malaysian and Brunei Newspapers: An International Union List (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 1992), ix. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 016.0795957 LIM-[LIB]); Ilse Sternberg, “The British Museum Library and Colonial Copyright Deposit,” The British Library Journal 17, no. 1 (Spring 1991): 62. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Acts of the Government of India, from 1834 to 1838 Inclusive: Presented in Pursuance of Act 3 & 4 Will. 4, c. 85, s. 51 (London: House of Commons, 1840), 22–24. (From National Library Singapore, microfilm no. NL30789; accession no. B20020347G) ↩

-

Sternberg, “The British Museum Library and Colonial Copyright Deposit,” 63. ↩

-

Sternberg, “The British Museum Library and Colonial Copyright Deposit,” 63–64. ↩

-

Acts of the Government of India, from 1834 to 1838 Inclusive, 125. ↩

-

Acts of the Government of India, from 1834 to 1838 inclusive, 126–31. ↩

-

Ilse Sternberg, “The British Museum Library and the India Office,” The British Library Journal. 17, no. 2 (Autumn 1991): 153. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Sternberg, “The British Museum Library and Colonial Copyright Deposit,” 73–74. ↩

-

“Monday, 15th November, 1886,” Straits Times Weekly Issue, 6 December 1886, 9; “Draft Minutes of the Legislative Council,” Straits Times Weekly Issue, 29 November 1886, 9; “The Book Registration Ordinance of 1886,” Penang Patriot, 27 July 1898, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

The Press and Registration of Books Act, 1867 (25 of 1867), Advocate KHOJ, 22 March 1867, https://www.advocatekhoj.com/library/bareacts/pressandregistration/; Straits Settlements, The Acts and Ordinances of the Legislative Council of the Straits Settlements, from the 1st April 1867 to the 7th March 1898, vol. 2, 1886–1898 (London: Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1898), 967. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 348.5957022 SIN)) ↩

-

Patricia Lim Pui Huen, Marion Southerwood and Katherine Hui, Singapore, Malaysian and Brunei Newspapers: An International Union List (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 1992), ix. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 016.0795957 LIM-LIB]). The Raffles Library’s annual reports from 1903 to 1939 mention receiving annual donations of books from the government of the Straits Settlements or the Colonial Secretary, which could have included the deposit copies. ↩

-

Raffles Museum and Library, Annual Report 1893 (Singapore: The Museum, 1894), 5. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 027.55957 RAF; microfilm no. NL25786) ↩

-

Seet, A Place for the People, 38. ↩

-

“Legislative Council,” Straits Echo (Mail Edition), 5 November 1919, 1786. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

The Chinese Protectorate (later known as the Chinese Secretariat) was established in 1877 to oversee matters regarding the Chinese community in the Straits Settlements. A Protector of Chinese was appointed to head it. For more information, see Irene Lim, “The Chinese Protectorate,” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published December 2021. ↩

-

“Untitled,” Malaya Tribune, 8 November 1930, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Legislative history from the National Library Board Act 1995, Singapore Statutes Online, last accessed 28 March 2025, https://sso.agc.gov.sg/Act/NLBA1995. ↩

-

E.J.H. Corner and L. Birtwistle, Report of Raffles Library & Museum, (Typescript), 1945–1946, 6–7; Annabel Teh Gallop, “The Perak Times: A Rare Japanese-Occupation Newspaper from Malaya,” British Library Asian and African Studies Blog, 13 May 2016, https://blogs.bl.uk/asian-and-african/2016/05/the-perak-times-a-rare-japanese-occupation-newspaper-from-malaya.html. ↩

-

The Archivist was a separate post from the Librarian and took charge of the Straits Settlements archives transferred from the Colonial Secretary’s Office as well as the newspapers and maps collection kept in the storeroom; these were mostly unsorted and uncatalogued. From 1939, the Archivist reported separately from the Raffles Library in the annual reports of the Raffles Library and Museum. Raffles Museum and Library, Annual Report 1938 (Singapore: The Museum, 1935–39), 1. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 027.55957 RAF; microfilm no. NL25786); Raffles Museum and Library, Annual Report 1948 (Singapore: The Museum, 1949), 5. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 027.55957 RAF; microfilm no. NL25786) ↩

-

Raffles Museum and Library, Annual Report 1950–54 (Singapore: The Museum, 1951–55), 11. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 027.55957 RAF; microfilm no. NL25786) ↩

-

“Malaya, S’pore Lack Library Facilities,” Singapore Standard, 1 June 1955, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Fiona Tan, “Pioneers of the Archives,” BiblioAsia 15, no. 1 (April–June 2019): 14–20. ↩

-

Raffles Museum and Library, Annual Report 1957 (Singapore: Raffles Museum and Library, 1958), 1. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 027.55957 RAF; microfilm no. NL25786) ↩

-

Cecil Byrd, Books in Singapore: A Survey of Publishing, Printing, Bookselling and Library Activity in the Republic of Singapore (Singapore: Published for the National Book Development Council of Singapore by Chopmen Enterprises, 1970), 103. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 070.5095957 BYR) ↩

-

Raffles Museum and Library, Annual Report 1957, 1; Seet, A Place for the People, 106. ↩

-

Gloria Chandy, “Herein Lie ‘Secrets’ of Our Heritage,” Straits Times, 1 December 1978, 21. (From NewspaperSG); Byrd, Books in Singapore, 103–104. ↩

-

Seet, A Place for the People, 122. ↩

-

E. Klass, “Why Locally-Printed Books Must Go to the N-Library,” Straits Times, 8 November 1976, 14. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Straits Settlements Government Gazette, vol. 21, Apr–Jun 1887 (Singapore: Government Printing Office, 1887), 900–01. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 959.51 SGG; microfilm no. NL1016–NL1023) ↩

-

“First Issue of National Bibliography Is Out,” Straits Times, 9 August 1969, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

The physical collection of books deposited with the National Library has been made available for reference and research since 2015, while the electronic collection can be viewed at a designated computer terminal at Level 11 of the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library at the National Library Building on Victoria Street. ↩